Believe me; I didn't ask for the assignment of editing this manuscript. Evidently the publixher's mother is a friend of the wife of the translator (Dr. Edgar Filbert Thomasson), or they are in a club together, or something like that. I read it; it was neither fish nor fowl. Since Dr. T. refused to let anyone verify its authenticity, it would be a scandalous disaster as an academic text. For all that I know, the whole thing is a fraud.

Although Dr. T. envisioned sales in the millions, it didn't impress me as a popular release either. For one thing, he mimicked the author's horribly antiquated style in much of the first chapter. He also inserted an ungodly number of notes, which he insisted be presented as footnotes rather than endnotes. Believe it or not, fifty-four footnotes weigh down the first two chapters alone!

Then there is the subject matter. The setting is Italy in the dark ages, and I, for one, had not heard of a single person mentioned in the book. Just getting through the first few chapters required the perseverance of Helen Keller. Needless to say, there is also no niche market for first-person historical treatises on an eleventh-century papacy. So, why read it?And yet … My job required me to read the whole thing several times, and there is definitely something there. The plot includes sex, family conflicts, mysterious deaths, a bunch of powerful kings and emperors, and a few twists that truly surprised me. Did I mention sex?

As for style, don't expect Hemingway or Faulkner; the English version was written by a man who has spent his life making sense of obscure Latin and Greek constructions. I encouraged him to make the text more conversational, but his colleagues are all classicists, and this is how they actually converse. However, I can affirm that after eighty-five sets of revisions most of the text is now somewhat readable.

I devoted a good deal of time to documenting how a reader could enjoy the good parts of this book without slogging through the other stuff. Everyone considers Moby Dick A masterpiece, right? Nobody reads it from cover to cover. All those details of nineteenth-century whaling bore people in the internet age.

Here is my recommendation for getting the most out of this book with the least effort:

- If you have a compulsive and unquenchable interest in the minutiae of one of the following topics—medieval European history, Church history, or the papacy:

- Pay careful to the Translator's Notes so that you can evaluate the rest of the text.

- Read all of the book except for #2B below, including the footnotes. You can just skim Chapter 11. Most of it recounts two hormonal young people whining to each other about not being able to do as they please.

- Keep a laptop handy. In addition to your notes, you will probably want several spreadsheets open in order to maintain an accurate timeline and record other details. Google and Wikipedia can help.

- If you are simply looking for an interesting story that is unlike any you have ever read:

- Do not read the Translator's Notes.

- Also skip the beginning of Chapter 1. Start with the paragraph that begins “My mind possesses ...”. Here is what you will have missed: The author's name is Theophylact. His family, which lives a few miles southeast of Rome in Tusculum, runs the show in both the papacy and the entire “Petrine Patrimony”, an independent country that stretches across the middle of the Italian peninsula from one coast to the other.

- Skip the footnotes. There are only two critical pieces of information in them.

- The translator uses the word “gorzo” because he is too polite to use a technical or slang term for male reproductive organs.

- You are not alone; the translator does not know what a “Baldocax” is either.

- Skip the first part of Chapter 8. Start with “I also exchanged letters with Prince Casimir.”

- Skip the first part of Chapter 9, too. Start with “In 1044 my father ...”

- Skip all of Chapter 12 except the last paragraph.

- If the Catholic stuff or the Italian stuff bothers you, just pretend that the story is set in Tibet or Borneo or on another planet. Pick a location—real or imagined—in which the recognized religious leader is also, for whatever reason, the monarch of a small country that has no real army and no set rules for succession of its leaders.

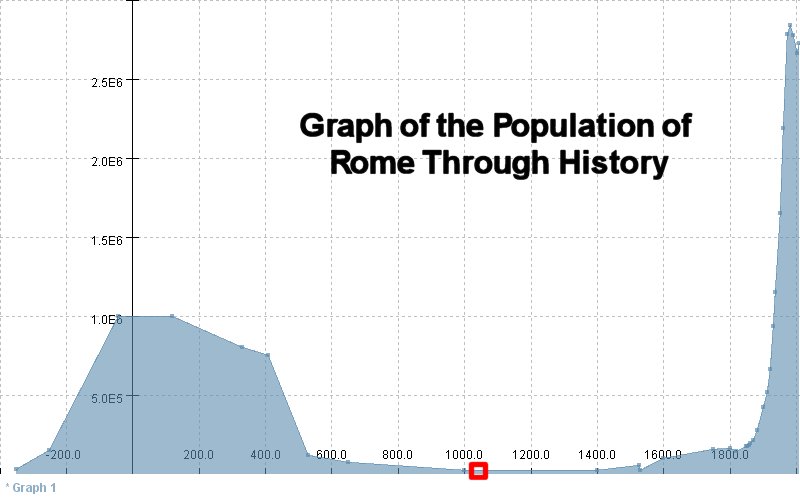

The map of Italy in the eleventh century and especially the population graph of Rome over the centuries should be useful to anyone. .

Fair warning: You may not find the protagonist particularly appealing. Keep in mind that his life probably included more than he was willing to share with posterity. Consider this the whitewashed version.

I hope that this helps.

Audrey Phillips

Editor

Translator's Notes:

Lawyers and others with whom I have consulted have strongly advised against disclosing the source of this manuscript. Each reader must therefore assess the reliability and accuracy of the text with a limited acquaintance with its provenance. I can confidently relate that experts have verified that its contents are reasonably consistent with its purported time (the eleventh century) and setting (Rome and its environs). Furthermore, to my knowledge no one involved with the manuscript's history stands to gain monetarily (or in any other way) by promulgation or, for that matter, suppression of its startling contents. These observations do not, of course, demonstrate that the manuscript is legitimate, but they surely render it worthy of close scrutiny.

Its discovery occurred in the course of examining some very large bound volumes of parchment that were part of a set of seventeen. Storage in well-constructed cases had limited the exposure of the parchment to corrosive elements. The seventeen volumes contained fairly accurate hand-written copies of St. Jerome’s well-known fifth-century translation of the New Testament into Latin. Experts examined the text and dated its origin with a remarkable degree of certainty to the end of the twelfth century. This is very important because it means that it was written in the eleventh or twelfth century, i.e., the Middle Ages. The author knew Latin and Greek, was extremely familiar with the Tusculan pontificates, and had no use for monks. The number of people who meet these criteria is quite small.

The collection’s total assessed value, which was less than $100,000 in 2002, was solely attributable to its age and rather remarkable preservation, not to its content. The quality of the rubrics, marginalia, and illuminations may have enhanced the assessment somewhat, but experts have asserted that they were hardly exceptional.

A colleague, whom I will call X, has requested anonymity. X examined each volume of the manuscript in detail in the course of research for a doctoral dissertation in a technical area. Evidently the pedestrian nature of the text had theretofore provided no incentive for scholars to examine the materials very diligently. X discovered that in the sixth through fifteenth volumes many pages appeared to contain palimpsests. That is, before the New Testament text had been written, the parchment had evidently been scraped clean of previous writings. The scarcity of parchment impelled writers and copyists in the Middle Ages to use milk and oat bran to remove the ink on existing manuscripts in order to reuse the parchment for the purpose at hand.

Familiar with my interest in palimpsests and my lifelong fascination with ancient Greek and Latin texts, X contacted me through a third party. I made discreet inquiries and eventually arranged to acquire all seventeen volumes through an agent. The volumes had been the property of a private collector. No government, religious, or academic institution was in any way involved in the transaction. I freely admit that I paid a substantial finder’s fee to X and allowed X to complete the original research project after I acquired possession of the volumes.

I subsequently undertook the lengthy and expensive task of employing multi-spectral imaging to retrieve the scriptio inferior that provided the source material for this work. I was assisted in this undertaking by colleagues at a large American university who have asked not to be identified. I am grateful for their invaluable help, and I will certainly respect their wishes.

Responsibility for translating the text of the palimpsest into English was mine. However, I consulted colleagues at my own university and others with respect to numerous difficult passages. For reasons that are amply explained within the the text of the document, the author's writing was quite often cramped and barely legible. He regularly intermingled Latin, Greek, and vulgar expressions, and his punctuation, spacing, and diacritical markings were unreliable and inconsistent. Abbreviations, elisions, and misspellings abounded. The quality of the penmanship was low even in the first lines and deteriorated markedly thereafter. On alternate lines the author wrote the characters from right to left. Furthermore, the pages were not in the correct order, and there is rather clear evidence that pages are missing. In short, the project of translating the document required almost as much skill in cryptography as linguistics.

The author claims to be Theophylact of Tusculum, better known today (by those who are familiar with him at all) as Pope Benedict IX, perhaps the most notorious of all of the medieval pontiffs. This audacious assertion of identity and numerous other claims within the text are bound to provoke controversy. Medieval history, Church history, and Italian history do not lie within my areas of expertise. I cannot therefore vouch for the authenticity of any of his claims. Others more familiar with the times and customs will be far better equipped to assess the accuracy of the details of the text. I can think of no one besides Theophylact with the ability and motive to produce it, but I could be wrong.

In the course of my involvement with the translation, I consulted many works to provide an understanding of the period and the purported author. Unfortunately, I found an embarrassing paucity of relevant information. At the time the number of people with the wherewithal to compose and publish written records was quite small. Furthermore, the authors of much of the contemporaneous material were Benedictine monks, a group that the author decries as unscrupulous and vicious political rivals. Most contemporary references to Pope Benedict are from those allied with the monks who opposed Theophylact and his family and associates.

I unearthed not one contemporary with anything positive to write about Pope Benedict IX. On the other hand, his reign—and for centuries both before and after his pontificate the pope was effectively the monarch of a strip of central Italy stretching from coast to coast—as Supreme Pontiff was the longest of all popes of the eleventh century. Moreover, from all indications Benedict IX's pontificates were, when compared with the other popes of the period, relatively peaceful and free from crises, especially if one discounts the attempts to overthrow him. For reasons that are not clear to me most historians ignore this seeming dissonance or proffer a dismissive description such as “Benedict IX—a grown man and not a child at his accession, but nevertheless an undistinguished and negligent man, whose retention of the papacy for twelve years [sic] seems a tribute to the entrenched power of his family rather than his own ability.”[1]

In point of fact, criticism—or even mention—of Pope Benedict’s policies, ideas, and philosophy is surprisingly rare. Instead, his critics have vilified him for his private life, which, according to some, was diabolical, worse than that of any other pontiff before or since. Although he remains the only pope who showed much interest in entering into matrimony with a woman, he has also been portrayed as a homosexual. The picture that emerges is of an extremely dissolute young man who neglected his duties for approximately thirteen years (roughly as long as Franklin Roosevelt's presidency) and yet somehow stayed in power—without a standing army or contracted mercenaries. His reign was not only one of the longest, but also one of the most peaceful, and most prosperous periods for the Petrine Patrimony during all the Middle Ages. His family was undoubtedly powerful, but that alone cannot explain this anomaly. The three Tusculan pontificates, of which Benedict IX’s was the last and longest, avoided or suppressed the chaos and violence that characterized the rule of other popes not only in the eleventh century but also in previous and subsequent centuries. That so little mention is made of this astounds me.

The fact that the manuscript emphasizes Pope Benedict’s personal life and relationships rather than his policies, his philosophy, and his actions as pontiff is at once disappointing and understandable. He clearly intended it as an apologia, and none of his enemies, then or later, attacked his policies or philosophy. Instead, they accused him and his associates of behavior that was so outrageously sinful and had brought so much shame upon his pontificate that it was no longer valid.

Readers may reasonably question why I decided against making the original manuscript, or even photocopies thereof, available to other academics. Let me emphasize that I have expended an enormous amount of capital (at least by my standard) and effort (by anyone’s standard) to the production of this tome. While I admit that turning the manuscript itself over to other experts might better serve the goal of scientific and academic advancement, it would be, to say the least, financially imprudent for me to do so. I value the importance of sharing one’s findings with one’s peers as much as anyone else in academia. This decision is not necessarily final, but at this point my top priority must be the recovery of my investment, and in my judgment and the judgment of my legal team, pursuit of that goal requires strict control over access to the documents.

Every translation project necessitates difficult decisions regarding the extent to which it seems appropriate to provide transliterations of the original text versus the employment of terms and styles more familiar to modern readers while still preserving the perceived original intent. I have, of course, striven to maintain the feel of the author’s style. Nevertheless, I have often needed to update the vocabulary and syntax for readability purposes. In particular, the text contained a strikingly large number of ablative absolutes. Since this form is seldom seen in modern English, I converted many such phrases to dependent clauses.

I excluded nothing, no matter how banal the subject matter was, how inaccurate the text appeared, or how poorly expressed the opinions seemed to me. The only additions are the footnotes. I felt that it was absolutely critical that the published volume should reflect, as closely as possible, the original author’s intent. In some cases this no doubt resulted in prose that falls short of twenty-first-century literary standards. For that I beg the reader’s indulgence.

Likewise I hope that readers are not overly annoyed by the rather large number of footnotes that accompany the text. I judged that the history and even geography of eleventh-century Italy are so far removed from the consciousness of twenty-first-century readers that most would have great difficulty in making sense of large portions of the text without such assistance. Little has been written by or about the principal characters in this manuscript, and, of course, most of those documents are not in English. Of the small sampling available, most twenty-first-century readers, even those in academia, will have encountered, at best, brief summaries. Furthermore, almost all of the contemporaneous extant material was recorded by just a few people, the majority of whom were monks who identified themselves as “reformers.” I expect that scholars of medieval European history throughout the world will find the opportunity to read the words of a knowledgeable person who was definitely not in that group an exciting prospect.

A word about the names is in order. For those people who have been mentioned in other historical documents, I used the names most commonly employed in the United States. The people called Gregory and Gerard were, of course, not called by precisely those names in eleventh century Italy. I left the names of people with no previous references, specifically Costanza and Tigra, as the author spelled them.

Finally, I would like to posit a few words about the disdain shown in this work for some peoples and cultures. The author freely uses terms such as “Jew” and “barbarian” in ways that would be considered offensive or even outrageous today. In the eleventh century, however, nearly all of western Europe was Christian, and it had been so for centuries. The Jews were the only non-Christians who were tolerated at all in the Papal States. Moreover, within a few decades after Benedict IX's ouster the treatment of this group became much worse. By the standards of the day, the author's views are probably no worse than commonplace.

As to considering the people north of the Alps as “barbarians,” this was primarily a reflection of their languages. Rome at the time was no longer the center of civilization. It had become a rather small inland community. The Germanic languages must surely have sounded very strange to it inhabitants, who spoke only Latin and the vulgar dialects and who had been exposed to nothing else except, in a few cases, Greek. To the author and to many others in this age and locale the consonant-laden sound of Germanic languages perhaps came to represent the triumph of ignorance (and therefore barbarism) over the Greek and Roman civilizations.

I sincerely hope that every reader will sympathize with the sensitive and difficult nature of this project and share my thrill at the insights that it might provide.

Edgar Filbert Thomasson

Professor Emeritus

Classics Department

THE Ohio State University

Columbus, OH, USA

August, 2019

[1] Peter Partner, The Lands of St Peter, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1972, p. 105. Benedict IX’s first pontificate lasted approximately twelve years and three months. If one considers Sylvester III an antipope, then Benedict’s total tenure was well over thirteen years.