The actual training Continue reading

The first few days of our training were devoted mostly to administrative matters. We got our gear, found our platoon and our bunk, and had a few sessions with our drill sergeant to make sure that we knew how to stay out of serious trouble. There was a heavy emphasis on cleanliness. I have always been a slob, but I expected to need an attitude adjustment for a couple of years. The only part that really annoyed me was “policing the area” every morning. We all walked around the barracks and picked up trash, mostly cigarette butts discarded by the nicotine addicts who were enabled by the Army’s pricing at the PX: fifty-cents per pack.

The only formal teaching that I remember from those first few days was a lecture by the chaplain. He inveighed for close to an hour about cursing. He was, not too surprisingly, against it. He was especially appalled by expletives that involved mothers. He spoke tenderly about his own mother, and he asked all his listeners to bring to mind images of their mothers before they used any kind of rough language.

I have argued that the 1095 oration in Clermont by Pope Urban II that launched the First Crusade was the most successful ever in terms of results. This speech by the chaplain certainly would rank at the other end of the spectrum. In fact, it is very hard for me to imagine that there could possibly have been more cursing in our company in the next seven weeks than there actually was. Virtually every sentence out of anyone’s mouth was replete with imprecations. The word “fuckin'” was the most common, and it was an ongoing challenge to insert it in the most unlikely place in the sentence. Consider this masterpiece: “What bullshit have they got for us this after-fuckin’-noon?” “Mother” was added perhaps half of the time.

Everyone took aptitude tests during the first week. I remember five of them: math, English, listening to dots and dashes, mechanical aptitude, and language aptitude. I hated the mechanical aptitude test. They showed pictures of tools with no scale provided and asked what they could be used for. If the tool did not look familiar, you could not determine whether its length was two inches or ten feet.

My dad told me that he had scored so badly on a similar test in World War II that they accused him of cheating on the other tests. No one called me on my score, but it was definitely out of line with the others.

The English and math tests were scored like IQ tests—100 was average, 115 was one standard deviation higher, 130 was two standard deviations higher, etc. Together they are called the GT test. The top score was 160. I got 160 in English and 152 in math. I thought that I had answered all the math questions correctly, but I must have made a mistake or two.

The language aptitude test was limited to those with a certain minimum score on the English test. Around 20 percent of us qualified. The test presented a made-up language with a list of vocabulary and syntax rules. The language had no suffixes or prefixes, but it did have infixes that consisted of two or three letters somewhere in the middle of the word. They could change singular to plural, present to past, or anything that a prefix or suffix could denote in more familiar languages. I learned of infixes from the workbook for the linguistics class that I took at U-M earlier in the year. I enjoyed taking this test, but most guys spent a lot more time just looking dazed than answering any questions.

Afterwards, while we were waiting in place—which we often did—a sergeant called out an approximation of my name. He told me to report to a certain captain in the training building. The captain informed me that I had received the highest score on the language aptitude test that he had ever seen. He then asked if I would be interested in volunteering for the Army’s language school in Ft. Lewis, WA.

Ignoring the warning from my drill sergeant about the perils of volunteering, I told the captain that I would like to go to this school. I did not even question him about what languages they taught and what duties the people who learned them performed. I foolishly imagined myself as a translator attached to an embassy in an exotic location. Maybe I would prevent a war by avoiding the use of the inflammatory word “upstart”.

Ignoring the warning from my drill sergeant about the perils of volunteering, I told the captain that I would like to go to this school. I did not even question him about what languages they taught and what duties the people who learned them performed. I foolishly imagined myself as a translator attached to an embassy in an exotic location. Maybe I would prevent a war by avoiding the use of the inflammatory word “upstart”.

One of the first and most important things that our drill sergeant taught us was how to perform the role of fireguard. He showed us where the fire extinguisher was. He might have even shown how to use it. The most important thing was to wake everyone up if there was a fire.

My recollection is that lights went out at nine, and the day started at five. I might be off a little bit. During the lights-out period someone on each of the two floors of the barracks was required to be awake. There were four fireguard shifts every night lasting for two hours each. Because most guys were accustomed to staying up later than nine, the first shift was the most popular. I was accustomed to awakening early, and so when I had to stand watch I tried to get the last shift. The men on this shift bore the additional responsibility of waking everyone up, a task that I relished. My technique for getting everyone out of the sack was to walk up and down the center aisle banging two trash can lids together while singing “It’s another be good to mommy day” from the Captain Kangaroo show. You can listen to the official rendition here.

We began every day with physical training (PT). Mostly we did pushups and jogged. We also did the monkey bars and a few other exercises. I have always loved physical exertion, and this was one of my favorite aspects of Basic. I put on a little weight, but it was all muscle. At the end of training we had timed tests in all of the areas emphasized in PT. I did pretty well, especially in my weakest activity, the monkey bars. I had never been in better shape, and until I started running fairly seriously I did not reach that level again.

Everyone in our company was issued an M16, the rifle used in Vietnam. A high percentage of our training involved this rifle.

Everyone in our company was issued an M16, the rifle used in Vietnam. A high percentage of our training involved this rifle.

Here is how we learned that we should always refer to the M16 that we were allotted as a rifle or a weapon, never a gun: Each guy held the M16 in his right hand over his head. The left hand was on his crotch. Then we recited:

“This is my weapon” moves right hand up and down.

“This is my gun” moves left hand up and down.

“This is for fighting” moves right hand up and down.

“This is for fun” moves left hand up and down.

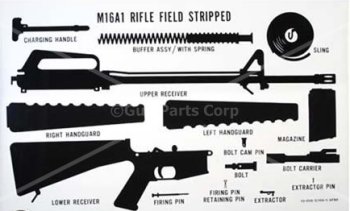

Before we learned how to fire the weapon, we were taught how to disassemble it and then put it back together. This is called “field stripping.” We were also taught how to clean it. This was very important. In those days M16’s had a bad reputation for jamming in the field. I don’t remember anyone in our company having trouble, but once we trained with another company that had a lot of jams. Every rifle that I saw jam was full of muck. Those guys must have never cleaned them.

Before we learned how to fire the weapon, we were taught how to disassemble it and then put it back together. This is called “field stripping.” We were also taught how to clean it. This was very important. In those days M16’s had a bad reputation for jamming in the field. I don’t remember anyone in our company having trouble, but once we trained with another company that had a lot of jams. Every rifle that I saw jam was full of muck. Those guys must have never cleaned them.

We got a fair amount of target practice. We were taught to keep the weapons “up and downrange”. It seems that most people now hold rifles with the barrel down. If it somehow fired in that position, the round would certainly ricochet off the ground in an unpredictable manner. If the rifle is held up, the bullet goes up. It will come down, but it will be traveling at terminal velocity, and the likelihood of hitting someone would be very low.

These rifles have no kick at all, and they are very accurate. I could consistently hit a human-sized silhouette at 300 meters, and I have terrible vision and coordination. I easily qualified when they scored us shooting at bullseye targets.

I have no recollection of anything going wrong with our rifles. Nobody shot himself in the foot. No one lost his weapon. However, there was one occasion in which I feared that my goose was cooked.

We were out in the pine woods for some reason, and we had a very long break. The ground was covered with pine needles. I had already finished the book that I was carrying. I decided to strip down my rifle and clean it. When I went to put it back together, I could not find the firing pin, which is metallic and looks like a nail and a spring that is part of the “fully automatic” feature that turns the M16 into a machine gun.

Some guys helped me look for about fifteen minutes, but the thick cover of pine needles made finding the spring hopeless. Maybe my rifle was missing it when I got it; I would not have noticed. I could not understand why we could not find the firing pin, and the rifle would not fire without it.

The sergeant called us to “fall in” to formation for the march back. I was panic-stricken. My rifle would not work without the pin of course. I would be found out very soon, but at least we had no more shooting scheduled that day. I could not think of any way out of this that was not fraught with peril. I decided to wait until we got back to the barracks to decide what to do.

When I got undressed the firing pin fell out of my trousers. To this day I have no idea how it could possibly have gotten inside my pants (we had to blouse our trousers with cloth covered rubber bands) or how I could have failed to feel it. I was so relieved to find it that I didn’t spend a lot of time trying to work out the physics.

This episode says a lot about the mentality of trainees. How much could a firing pin cost? $5? Probably less; fifty years later one costs $8.99. Nevertheless, the idea of having to admit that I had lost such a thing was terrible to consider. I felt sure that I would have been browbeaten in private and probably humiliated in public.

After I put the firing pin in, the rifle worked fine as long as it was not switched into “rock and roll” mode, which we were never allowed to use. So, I was still in the clear until we had to turn in our weapons in the last week during the dreaded “white towel” test.

A sergeant sat at a desk with a stack of white towels. We all got busy wiping away every last speck of dirt or oil from our rifles. Finally a bold trainee sidled up to the desk with his stripped weapon laid out on a towel. I was waiting for this, but a handful of guys preceded me in line behind him. When the first guy reached the desk, the sergeant asked him if his weapon was clean. He paused, grinned a little, and then said, “I think so, sergeant.” The sergeant took a piece of the rifle, rubbed it on a towel, and made a smudge. Rejected. The next few guys made equally non-assertive responses to the sergeant’s initial queries, and their weapons were all rejected.

A sergeant sat at a desk with a stack of white towels. We all got busy wiping away every last speck of dirt or oil from our rifles. Finally a bold trainee sidled up to the desk with his stripped weapon laid out on a towel. I was waiting for this, but a handful of guys preceded me in line behind him. When the first guy reached the desk, the sergeant asked him if his weapon was clean. He paused, grinned a little, and then said, “I think so, sergeant.” The sergeant took a piece of the rifle, rubbed it on a towel, and made a smudge. Rejected. The next few guys made equally non-assertive responses to the sergeant’s initial queries, and their weapons were all rejected.

When he asked me if mine was clean, I loudly affirmed, “Yes, sergeant.” He replied, “Well, then turn the motherfucker in.” I quickly complied, and I felt a surge of relief.

A light bulb shone over the head of the guy behind me. When the sergeant asked him if his rifle was clean, he replied “Yes, sergeant” even more loudly than I did. The sergeant responded, “Well I guess I’ll be the judge of that, won’t I?” He quickly found a dirty spot and rejected the rifle.

After a few hours of this nonsense‐all of these weapons were already very clean‐everyone’s weapon was accepted, and the whole company was joyfully disarmed.

We carried our weapons with us everywhere except on PT excursions. We were actually lucky. The M16 was much lighter than its predecessor, the M14, because in several areas light-weight plastic replaced steel or wood.

The coolest part of training was the afternoon that they showed off some of the Army’s other weapons. We got to see a light anti-tank weapon (not a bazooka!). An armored vehicle was out in the field 60 or 70 yards away. An instructor put the tube-like LAW on his shoulder, zeroed in on the vehicle, and pulled the trigger. A rocket ignited in the tube and then slowly made its way to the vehicle. When it got to the target, it burrowed through the armor and then exploded.

The M60 machine gun was also impressive. It had so little kick that the presenter put the stock right in his crotch and fired off a burst. It goes without saying that we maggots were not allowed to get our hands on either of these.

The M60 machine gun was also impressive. It had so little kick that the presenter put the stock right in his crotch and fired off a burst. It goes without saying that we maggots were not allowed to get our hands on either of these.

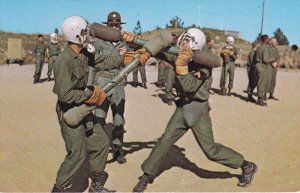

The only face-to-face combat training was in the use of the bayonet. We learned that you use the pointy end to stab someone. You can use the stock end to bludgeon someone. We then showed that we had absorbed this lesson by attacking some straw figures. They did not let us use real bayonets.

I assume that this technique would come in handy if you were by yourself and your rifle was lost, broken, or out of bullets AND you had an opponent who was in exactly the same position. This happens pretty often in the movies. Who knows about real life? All that I know is that my buddies and I are ready for it.

The other half of the bayonet training involved pugil sticks, which are about four feet long and, unlike bayonets, they have padding on both ends. The trainers paired us up with someone about the same size. My opponent was the guy who played the country music station on his radio every morning. He was a little bigger, but I, the dorkiest-looking guy in the company, was more highly motivated. To everyone’s surprise I pummeled him.

The other half of the bayonet training involved pugil sticks, which are about four feet long and, unlike bayonets, they have padding on both ends. The trainers paired us up with someone about the same size. My opponent was the guy who played the country music station on his radio every morning. He was a little bigger, but I, the dorkiest-looking guy in the company, was more highly motivated. To everyone’s surprise I pummeled him.

By and large our outdoor training was similar to what was shown in the movie Stripes. There was one major exception. There was no obstacle course and, therefore, there was no tower in which our drill sergeant to climb and get blown up in.

Instead we went out after dark one night to a field that we had to crawl across with our rifles across our arms. Barbed wires were strung a couple of feet over our heads. At the far end trainers were firing (allegedly) live ammunition, including tracer rounds, a little higher than the barbed wire. To my knowledge, nobody in our company got hurt. I don’t remember whether everyone completed the task or not. I doubt it.

Instead we went out after dark one night to a field that we had to crawl across with our rifles across our arms. Barbed wires were strung a couple of feet over our heads. At the far end trainers were firing (allegedly) live ammunition, including tracer rounds, a little higher than the barbed wire. To my knowledge, nobody in our company got hurt. I don’t remember whether everyone completed the task or not. I doubt it.

We also had a few other classes. I remember an outdoor class in which we were taught the rudiments of spotting different types of aircraft. What I learned from this class was that it was probably a good idea to save your ammunition for ground-based opponents.

There must have been others, but the only indoor class—aside from the insufferable chaplain’s lectures—that I remember was on map reading. I was astonished to discover that around half of the company was totally unfamiliar with the topic. For those of us who already knew how to read maps these classes were excruciating. I called them “nap reading”.

Several guys were indeed caught napping during indoor classes. Many had a difficult time adjusting to the routine of the routine of early lights-out and early wake-up calls. Also, the sergeants claimed that all trainees had a sleep button in their butts. Whenever they sat down they fell asleep.

Training was voluntary. The alternative every morning was to go on sick call. At the opening assembly, one of the sergeants would yell out “All sick, lame, and lazy report to …” A few guys tried this pretty often. I never asked them how it went.

I hated every minute of the experience, but Basic training had at least three beneficial effects on me. By the end I was in terrific shape. I learned that a moderate but consistent effort can produce a profound effect on your physical conditioning. I have never forgotten this.

Secondly, I got to know on fairly intimate terms some entirely different breeds of guys. To put it another way, the Army expanded my horizons. I don’t think it expanded them up, but any expansion helps.

Finally, I discovered that I was fairly gritty. I had a lot more endurance than most guys. I scored pretty high in the final physical training test. I more than held my own in most areas with guys that I would have thought were tougher than I was.