Taking classes in subjects in which I had little interest. Continue reading

Graduate school in the speech communications department1 at U-M was a joke. The department had several areas of study. The only thing that they had in common was that they all had something to do with making noises with one’s mouth. One of them was fairly rigorous—speech therapy, which dealt with solving the problems of people who have difficulty making certain sounds. All the others—communication theory, rhetoric, mass communication, theater, and oral interpretation (reading aloud)—were all squishy, with an abundance of theories and almost no science. The worst was oral interp. The students would read something aloud, and the professor would tell them what they did wrong. Often they would read a translation of a work originally written in another language! How could anyone take this seriously?

Because I was eligible for seven years of veterans’ benefits, I was reimbursed by the Veterans Administration for my tuition. The way that it worked was a little perverse. I was paying in-state tuition, and the rate was a little less than the amount of my benefits. However, if I dropped or failed classes, the payment from the Veterans Administration was not adjusted. They paid for classes, not success in classes.

As an undergraduate I had taken a few graduate-level classes in math and Greek. They were very challenging. I struggled to pass them. In contrast, none of the graduate-level speech classes that I took in my second stint at U-M were as difficult as my freshman math classes. I found it ridiculous that people who passed these speech classes were somehow on a par with people who had mastered math or science. I had very little interest in subjects I was learning, I devoted the absolute minimum time possible, and I still skated through with no problem.

I discovered that my previous approach to selecting classes may have been misguided. As an undergraduate I avoided papers like the plague. Graduate students in “social sciences” cannot avoid writing papers. I discovered that I was good at the type of expository writing that professors appreciate.

The very first class that I took, Introduction to Graduate Studies, provided the most entertaining session that I encountered in my ten years of college courses. The teacher was Rich Enos2, a rhetorician who had just received his PhD from Indiana University. The graduate students in speech at U-M came from all areas. So, some people wanted to learn about radio and television, some were studying film techniques, some wished to become actors, some wanted to read aloud (!), and a few, like me, allegedly wanted to learn the theory of communication or rhetoric. We were a really diverse group. Nevertheless all new students were required to take the same Intro course.

Most lessons in this course were real snoozers. We learned about the style required for papers and a few other things that I have long ago forgotten.

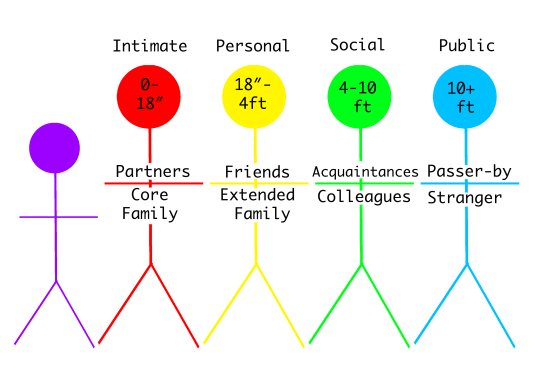

I will never forget however, the class conducted by guest lecturer Bob Norton3, who was asked by Rich to explain the use of statistics in speech. Instead, he chose for his topic the research in “Proxemics”, which deals with the effect of space between two people and their ability to communicate. He said that the measurement of the distance between two people was very controversial.

One of the currently accepted paradigms was the “nose-to-nose” method. This approach yields very different results from those of the “mouth-to-mouth” method, according to Norton, if one is talking about two Jews rather than two Chinamen (his words, not mine). He then proceeded to draw a lot of stick figures on the board illustrating problems of various types involving escalators, staircases, and, in one case, a Mexican peeing in a corner.

Almost all of the other students sat in stunned silence during this presentation. A few were even taking notes. I was laughing so hard that at one point I literally fell out of my desk. Don Goldman, who was sitting next to me, snickered a bit, but his heritage as a Southern gentleman prevented full appreciation of the farce.

When the presentation was over, Norton opened the floor to questions. One woman raised her hand and, when recognized, asked, “How do you do a T test?”

Norton answered, “Are you in theater?”

She admitted as much,. He said that that confirmed his suspicions, and he immediately asked if there were any other questions.

She insisted, “I really want to know.”

Norton waited a few seconds and then declared, “I don’t know. I always have to look it up.”

I have not done justice to this presentation. He must have devoted quite a bit of time to working on it. It was the most outrageous thing that I had ever witnessed in any medium. Enos was stunned at first and furiously angry by the end.

I spent a bit of time with both Enos and Norton, separately, of course—they did not get along. Dr. Enos was shocked to find out that I could read both Latin and Greek but had little interest in the ancient writings on rhetoric. I was equally shocked that he could not but did have.

Dr. Norton spent a lot of time with one PhD student who was using Norton’s “Communicator Style” construct in his dissertation. Every other student in the department was scared to death of him. Late one afternoon I went into his office, which was on the other side of the building, and asked him to explain Communicator Style (which now has at least 657 citations on the Internet). He opened the bottom drawer on the left side of his desk and extracted a bottle of sherry. He offered me a glass, but I demurred.

He explained that he had developed a series of questions that supposedly measured psychological trait. He postulated nine traits—dominant, dramatic, contentious, animated, impression-leaving, relaxed, attentive, open, and friendly. I don’t know what basis was cited for limiting the construct to these particular traits, and I don’t know how he determined that the questions actually measured the traits. In both cases he might have built on someone else’s work.

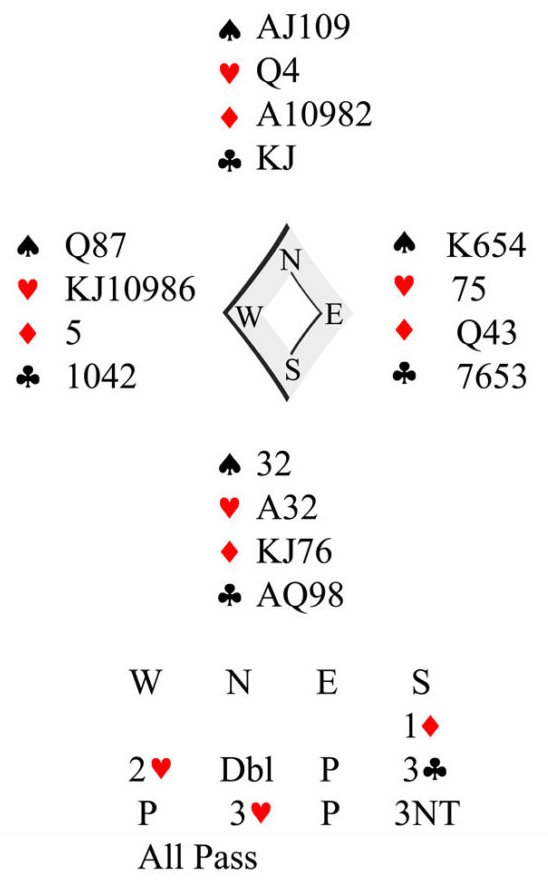

Norton’s contribution involved applying a statistical tool that someone had developed to show the “distance” between the traits in a group of subjects in two dimensions. There was not too much to this; it simply used the correlations between traits and produced a chart that minimized the tension between the thirty-six sets of correlations (dominant with the other eight, dramatic with the other seven, etc.). Traits were arrayed so that they were closer to the ones that they were highly correlated with and distant from the ones with which they had negative correlations.

A three-dimensional depiction would have been more accurate, and, for all that I know, he may have tried this. However, displaying it on paper for a book or journal article would be problematic. Going beyond three dimensions would be even more accurate, but no one would be able to envision the maps in n-space.

After I understood his approach, I objected that these depictions didn’t mean anything. Not only did they not represent how the brain—or anything else—was organized. They were actually less meaningful than the raw statistics. That is, simply listing the correlations between the various traits was more meaningful than visually depicting the distances between all traits in the construct. People allegedly felt that they understood the relationships if they could see a picture rather than a set of numbers.

He said that I missed the point. His Communicator Style construct could be used to study virtually any group of people who were willing to fill out his questionnaire. For example, he could take a group of debate coaches (or football coaches or politicians or members of any identifiable class) whom he could assess by some means. Since the construct had been accepted in the literature. he could write a paper that contrasted the communicator style of the successful ones with the construct of the less successful ones. The possibilities were limitless.

At this point he opened the bottom drawer on the right side of his desk and showed me a set of eight or ten papers that he had already written using this approach. He told me that he planned to submit one or two a year to various journals. I admitted to being impressed with his initiative and his laziness.

Evidently he went through with his plan. He published a book on this subject in 1978.

I took Dr. Norton’s statistics class. There were only four students: myself, Goldman, a woman who had attended Tulane and was working on her PhD, and a guy from the mass media area. Norton actually taught the material this time, but the other students had little or no exposure to math since high school, and they were definitely at sea in this class. I helped Goldman.

Norton invited some researchers to present their findings to the class. These guys had administered a lot of questionnaires to people in Toledo. I don’t remember the details, but they had expected to find a correlation between some answers and the result of some event. They were disappointed, but they did find an unexpectedly strong correlation between some other answers and something else.

Norton asked me what I thought about the presentation. I replied that it showed that if you get enough data, you are bound to find something. What they found may have served as the launching point for a separate study, but since what they found did not agree with the null hypothesis, it was not per se meaningful.

The statistics class only had one test, which was multiple-choice. Norton told everyone that he was going to penalize guessing. Did he ever! The scoring was straightforward: number right minus number wrong. I got a pretty good score even though I protested that one of his “correct” answers required a horse in a race to finish both first and second simultaneously. He saw my point, but he was too lazy to change the score. Goldman scored much lower. The woman’s score was just above zero. The mass media guy would have done better to turn in a blank sheet of paper. He had more wrong answers than right ones. Imagine the effect of getting a negative score on a final exam in graduate school.

My recollection is that no one signed up for this class the next semester.

The only class that I really liked was a seminar in Group Dynamics in the psychology department. It was taught by Dorwin Cartwright4. Our textbook, which was also called Group Dynamics, was written by Cartwright. Much of the time in class was spent explaining the ideas of his mentor, Kurt Lewin (pronounced leh VEEN), who was largely responsible for bringing statistical methods to the social sciences.

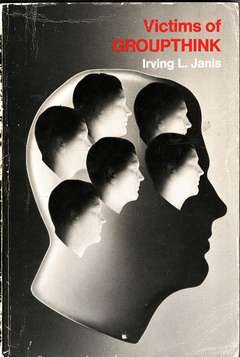

I was most interested in the research about “shift to risk”, a theory that groups are more likely to accept risky outcomes than individuals. Lewin helped design the original set of ten questions that had been used by many researchers to explore this topic. Some of these studies formed the basis for the best-selling book, Victims of Groupthink by Irving Janis. My final paper for Cartwright’s class was a review of this book, which, in my opinion ignored some important facts about the decision-making processes in both the Bay of Pigs incident and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

I don’t remember too much about my other classes.

- The course in Classical Rhetoric was taught by Dr. Enos. I got little or nothing out of it.

- Rhetoric of Social Movements was taught by a professor whose name I don’t remember. He liked me, and he especially liked the fact that I chose the worldwide anarchist movement for the topic of my final paper. However, he did not like the paper itself, which used Transactional Analysis to dissect the oratory. I concluded that the movement was doomed to failure from the start. He said that if I were right, it would be incoherent, which I certainly think was the case. You can’t herd cats, and you can’t organize anarchists.

- I took an undergraduate radio-television class overseen by another grad student. It had two projects. One I was completely unprepared for because I had been out of town on a debate trip. I extemporized a how-to presentation on filing debate evidence. The instructor liked it. On the other one, which was a short radio play in the style of Bob and Ray5, I worked fairly hard, and Don Goldman co-starred. The instructor didn’t think much of it, but the class really enjoyed it when he played the recording for them. I suspect that he thought that it had been serious.

- I missed a lot of classes in a programming course in Algol. When I finally showed up for a class, the instructor made me go to the blackboard (actually green) to explain something. It was embarrassing. I dropped the class rather than risk another such event.

- Don Goldman taught a course in directing forensics. Many of the debaters were also in it. None of us ever attended the classes. One day Don came to me and said that he might get into trouble if he gave all the debaters A’s. I told him to give me the B. I did not care two cents about my grades, and they were all concerned about getting into a good law school.

- I must have taken another class or two, but I can’t recall any.

One day I was walking rather rapidly on the sidewalk on North University. Books and stacks of papers occupied both hands. The lens popped out of my glasses and disappeared into a snowbank. I made a cursory search but found no trace.

About two months later I was walking in the same area and I spotted a lens in the grassy area between the sidewalk and the street. It was scored by deep scratches, but it was definitely the one that I had lost.

Masters candidates at U-M had a choice of writing a thesis or taking more classes. Since the VA paid me to take classes but did not pay me to research and write, I selected the leisurely method of taking more classes. I got my degree in 1976.

1. The speech department no longer exists. Most of the areas were appended to the journalism department. The resulting department is now called “Journalism and Screen Studies”. U-M now also has a communication department. I am not exactly sure what is in it. The theater and speech therapy areas are, I think, in other “schools”. Theater is in the School of Music, Theater, and Dance. The speech therapy people have their own department called “Speech-Language Pathology”, which I think is in the School of Medicine. The debate team is not associated with any of these departments.

2. According to his LinkedIn page Rich left Michigan in 1979 and taught at Carnegie-Mellon University for sixteen years. Since 1995 he has been at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth.

3. Bob left Michigan some time before 1978. He spent his academic career at the University of Wisconsin.

4. Dorwin Cartwright died in 2008. He has a short Wikipedia page.

5. Bob Elliott and Ray Goulding produced hilarious radio skits for the long-running NBC show, Monitor Radio. They were interviews or pseudo-dramas in which all of the characters were played by one of them or the other. My dad was a loyal listener to Monitor Radio. I found most of its offerings boring, but I loved Bob and Ray. I still have a copy of their book, Write if You Get Work.

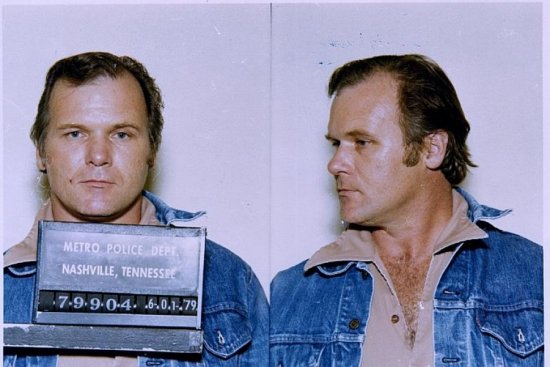

2. This horribly unimaginative song tied “California Dreamin'” as Billboard’s top song of 1966. Surely this was the worst song ever to become so popular. Sadler was a medic in Vietnam. His one hit made him a lot of money, but his life subsequently went quickly downhill. In 1979 he was charged with second-degree murder and pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter in Nashville. He went to prison for thirty days. In September of 1988 he was shot in the head in a taxicab in Guatemala City. He died early the following year.

2. This horribly unimaginative song tied “California Dreamin'” as Billboard’s top song of 1966. Surely this was the worst song ever to become so popular. Sadler was a medic in Vietnam. His one hit made him a lot of money, but his life subsequently went quickly downhill. In 1979 he was charged with second-degree murder and pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter in Nashville. He went to prison for thirty days. In September of 1988 he was shot in the head in a taxicab in Guatemala City. He died early the following year.