Athletic activities in the Hartford area: basketball, golf, etc. Continue reading

Swimming: The apartment building in which I lived in East Hartford had an outdoor swimming pool. I brought a bathing suit with me to Connecticut, and I spent some pleasurable hours sitting next to the pool. I may have also entered the water for short periods once or twice.

Basketball: Tom Herget and Tom Corcoran had discovered that pickup basketball games were often held on the asphalt court near Batchelder School. After I had been working for a week or so, they invited me to join them. At first I demurred, but Herget was very good at shaming people into joining the fun. A bunch of us played there on a regular basis.

It was a good court. We played a full-court game without a ref. The court was neither as long nor as wide as a regulation court, but it was quite adequate for a three-on-three or four-on-four game. The rims were regulation-height and quite sturdy.

Sometimes so many guys were there that we had two one-basket games. As often as we could, we played full-court.

Guys would come and go. The teams were fluid. I think that we kept score, but no one cared who won. There were arguments about fouls, of course, but I can’t remember anyone getting upset enough to do anything about it.

I can’t remember the names of any of the players except for people from the Hartford. Here are my most vivid recollections:

- A guy who played with us all the time had a unique shot. He was only 5’8″ or so, and he was not very mobile. If he got open, however, he would quickly bring the ball up over his head and launch a shot with virtually no arc that just cleared the front of the rim. When the ball made contact with the back of the rim it almost always dove straight down into the net. This was due to the fact that he somehow imparted an enormous amount of backspin to his shot. I was a great admirer of his shot; my attempts to emulate it were failures.

- Herget also had a devilish shot. He liked to drive right into an opponent’s chest and then scoop the ball underhand toward the basket behind the opponent’s back. He beat me with this maneuver many times even after Tom Corcoran showed me how to defend it—by keeping one’s own arms down and once he started the scoop just placing the hand on that side on top of the ball. Herget usually passed the ball away if Corcoran was guarding him.

- A couple of times an Emergency Medical Technician played with us a few times while he was on duty. He parked his vehicle near the court and left the radio on. I don’t think that he ever got any calls while he was playing. I wonder what he would have been doing if he wasn’t playing with us.

- I remember one magical day in 1974 when, for some strange reason, I could do no wrong on the court. On most days I missed three or four shots for every one that I made, but on the magical day my shooting percentage was certainly in the eighties or nineties. I got several rebounds and made some good defensive plays, too. It never happened again.

- Several times opponents—to their regret—brushed up against my very sharp elbows or knees. Once a guy’s thigh hit my knee harder than usual. I barely felt it, but he stopped playing and, as I recall, just limped to his car and drove home.

- One day in late May or June of 1974 we were playing a full-court game. I had the ball, and I was running at a good speed and dribbling while looking for an open teammate. Somehow I slipped or tripped and fell forward. I landed on the heels of my hand, but the top of my right knee hit the pavement about as hard as one might knock on a door. I cried out in pain, but when I rolled up the leg of my pants to unveil a small scratch, I was ridiculed by the other guys for stopping the game. I played for a few more minutes, but then my knee gave out, and I limped to Greenie and drove home. That was my last game at Batchelder.

On the way home I had to stop to buy something for supper, cauliflower I think. By the time that I reached the apartment in Andover in which I was living my knee was so swollen that it looked like a cantaloupe was stuffed in my jeans. Sue Comparetto somehow brought me to a doctor whose name I don’t remember. He took X-rays and determined that my patella (kneecap to you) had broken into several pieces. The largest one could stay, but the others needed to be surgically removed.

An ambulance took me to the Windham Community Memorial Hospital in Willimantic. I was assigned to a room with three older men, all of whom were there for hernia operations. One at a time, they each went to the OR before I did. The scenes were similar. The anesthetic was administered. The patient counted backward from 100. The first two were out buy 97. The third guy, however, was down into the seventies when they told him he could stop. I am not sure how they ever knocked him out. Maybe they just gave him something to stick between his teeth.

I, who have a mortal dread of needles, was much more apprehensive about the injection of the anesthetic than of the carving of my leg. They gave me the shot, and the next thing that I knew was that I was back in the room with a cast on my leg. The surgeon came to see me a little later. He asked me to lift the leg. I couldn’t do it. He said that I could not leave until I could lift it by myself.

In the day or two it took me to find those muscles again I had a few visitors. I am sure that Sue came. So did Jim and Ann Cochran.

I had a view of downtown Willy from my bed. I could either see a sign for Kentucky Fried Chicken of one of the colonel’s stores. In either case it gave me a strong incentive to raise my leg. I really wanted some fried chicken. I was released before any of the hernia guys.

My injury had a good side and a bad side. The benefit was immediate. I had been called up for summer camp by the Army Reserve. I called the phone number on the notice to report that I had broken my kneecap and could not come. The guy who answered—I took down his name, but I don’t remember it—assured me that I did not need to come. Since 1974 was the last year that I was eligible, I never had to atten reserve camp. I was not dreading the duty, but I did not want to return to work at the Hartford with a military haircut.

The bad side was that the surgeon missed one small piece of bone, and it eventually adhered to my femur. It did not bother me much for twenty-five years, but in 1999 I was diagnosed with tendinitis of the IT band. The doctor attributed it to that tiny piece of my patella. Some stretching exercises made the condition manageable, but in 2017 I got arthritis in that knee. This in turn has made it more difficult to keep the IT band from bunching up. I am not complaining. I have averaged walking five miles per day in the ten months starting in March of 2020, but I need to do a lot more stretching.

Golf: I started playing golf with John Sigler late in the summer of 1972. We played together every chance that we got, and we tried nearly every public course in the area. He was better than I was at every aspect of the game, but I enjoyed our outings together immensely. In 1973 we even took off many Wednesdays during the summer to play golf.

On one of those days in the summer of 1973 we drove down to Cromwell to play the Edgewood Golf Club. The layout was later redone to suit the pros, and the name was changed to TPC River Highlands. It was the most difficult course that I had ever played then, and they made it much tougher when they made it a Tournament Players Championship course in the eighties.

In 1973 John and I also played together at the annual outing of the Actuarial Club of Hartford in Moodus, CT. I did not remember the name of the course, but the only one in Moodus seems to be Black Birch Golf Club. It was a miserable day for golf—or anything else. The rain started halfway through our round, and it was also very windy. I seem to remember that John played well enough to win a dozen Titleists. I think that I won three Club Specials as a kind of booby prize. The highlight of the round for me was watching Mike Swiecicki ride merrily around in a cart and swatting at his ball with little care about the results. I also enjoyed playing bridge with John and a cigar-smoking Tom Corcoran. I don’t remember who was our fourth.

At some point John and I added Norm Newfield and Bill Mustard to our golfing group. Norm, who was a star quarterback and pitcher at Central Connecticut and the Navy1, worked in the Personnel Department. I think that Bill worked in the IT Department. Norm was a big hitter, and Bill was an absolute beast, but neither of them could control the ball’s flight like John could. I was definitely the wimp in this foursome. Most of the time we played at Tallwood in Hebron.

In 1974 John and I signed up to play in the Hartford’s golf league. The nine-hole matches were on Fridays at Minnechaug Golf Course in Glastonbury. I have always been better at team sports than individual ones, and it proved true again. Of course, John always played against the opponent’s better player. Still, we played seven or eight matches, and I tied won and won the rest. We were in first place in the league with only one or two matches remaining when I broke my kneecap. Our proudest achievement was defeating Norm and his partner, whose name was, I think, Bill Something. He probably worked in HR with Norm.

I remember one match pretty clearly. We were playing against two guys whom we did not know at all. I think that I had to give up six strokes, and John had to give up seven in only nine holes. John’s opponent had a new set of really nice-looking clubs. My opponent was from India, or at least his parents were. When I told this story to friends I usually called him “The Perfect Master”. We were afraid of a setup. Because of the handicap differentials, if they played at all well, we would have no chance.

On the first tee John’s opponent exhibited a monstrous slice, but the ball stayed in play. My opponent then hit the shortest drive I have ever seen. He did not whiff, but the impact was much less than Lou Aiello’s swinging bunt (described here). The ball stayed in the tee box less than a foot in front of his left shoe.

Neither John nor I could take the match seriously after that. We both played worse than we would have thought possible. Going into the eighth hole, the match was in serious jeopardy. However, the eighth, a short island hole, was always good to us. We both put our iron shots on the green. The opponents both plunked their tee shots into the water. The last hole cinched all three points for us when both of our opponents found the water again. We survived our worst match ever and, of course, enjoyed a beer afterwards.

Jim Cochran stepped in to take my place for the last few matches. Alas, John and Jim lost the championship match.

There was one other interesting golf adventure. Tom Herget arranged for John, Tom Corcoran, and I to join him for nine holes at the Buena Vista Golf Course in West Hartford. Par for this course is only 31 or 32. It is much easier than Minnechaug.

Herget evidently wanted to try out the golf clubs that he had purchased (or perhaps found in an alley) somewhere. They were at least six inches too short for him, and he is not tall. When he went to hit the ball, his hands were at knee level. Danny Devito is too tall for these clubs.

The round itself produced few memories. I do not remember the scores, but I do remember that Sigler shot in the thirties, I scored in the forties, Corcoran in the fifties, and Herget in the sixties.

Baseball/Softball: I remember that several of us drove up to Fenway for a game between the Red Sox and the Yankees. Somehow we got box seats in the upper deck right even with third base. I have been to games in four or five stadiums. This was by far my best experience. I remember eating peanuts, drinking beer, and yelling at the players and coaches. We were unbelievably close to them. It was more intimate than a Little League game.

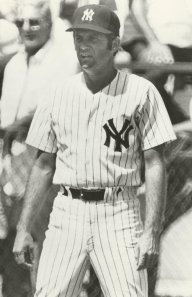

I channeled my inner Bob Anderson to loudly rebuke New York’s third-base coach, Dick Howser2, for mistakenly waving a runner home. He actually looked up at us. I remembered him as a so-so shortstop (after his promising rookie season) for the KC A’s. He had a goofy batting stance with his legs spread wide and his head about four feet off the ground.

I later felt a little guilty about my boorish conduct at Fenway when he became the Royals’ manager and in 1985 guided them to the my home town’s only World Series win. One must understand that people who grew up in KC in the fifties and sixties REALLY hate the Yankees.

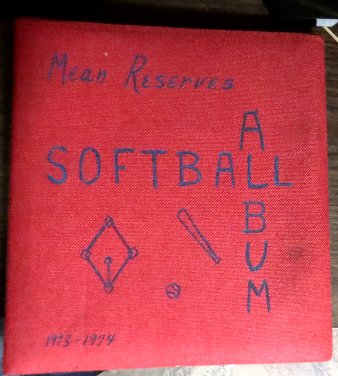

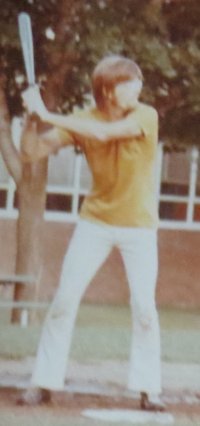

I remember going to watch Patti Lewonczyk play softball a couple of times. I do not recall whether the Hartford had a team in a city-wide league or an entire league of teams like the men’s. Patti was a good hitter, and she did not throw like a girl. I am pretty sure that Sue took photos on at least one occasion, but I don’t know where they are, and I dasn’t ask.

Football: On September 23, 1973, a group of us went to a football game between the Patriots and the Chiefs at Schaefer3 Stadium in Foxborough. I could not believe what a dump the place was. I don’t remember any details. The game was a real snoozer. The Chiefs held the Pats to only one touchdown, but they only scored ten points themselves, which was enough for a W. After that one magic season in 1969-70, the Chiefs quickly became an also-ran team for the next five decades!

I also attended several college games. The most entertaining one was on October 20, 1973. I rode to Providence in Tom Corcora’s Volkswagen for the game between Brown and Dartmouth. Dartmouth entered the game with an 0-3 record, but they beat the Bears 28-16. The Big Green went on to win all the rest of their its (their?) games that year. Brown finished 4-3-1, which was very good for Brown teams of that era.

The game was fairly interesting. There were no NFL prospects, but the Ivy League schools were famous for their trick plays. That is my kind of football.

Even more interesting was the rascally atmosphere that shocking for a deadly serious Michigan fan to experience. For example, one guy in the stands had brought a keg of beer as a date. The keg was wearing a dress and a blonde wig. This would never happen at Michigan Stadium. Alcohol was strictly forbidden at the games, and seats were precious possessions; nobody got two.

Dartmouth had never had an official mascot, but for decades most people called them the Indians. In 1972 the Alumni Association advised against this in favor of another nickname, the Big Green. The teams embraced this, but a set of alternate cheerleaders attended this game. They sat in the stands and wore identity-concealing costumes. One was a gorilla; I don’t remember the others, but none were Indians. Whenever the official cheerleaders finished a cheer for the Big Green, the alt-leaders rushed to the sidelines to lead the same cheer for the Indians. This went on without objection. It did not seem strange to anyone but me.

The Brown band played at halftime. Their uniforms were brown turtlenecks. Most people wore nondescript pants, but several had evidently played for the soccer or rugby team that morning. Their legs were muddy, and they wore shorts. A few of them also had comical hats.

The band formed itself into various formations, but our seats were too low to make sense of them. The stadium was not big. I doubt that many people could decipher them. The band members just ran to their spots for each formation. They did not march in the orderly fashion that I was used to. I think that the primary purpose of the entertainment was to make fun of Dartmouth.

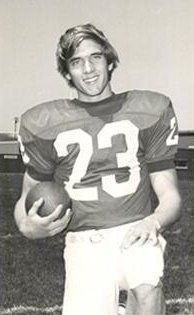

The very next Saturday I drove to Storrs by myself to watch a game between UMass and UConn. Both at the time were 1AA schools and members of the Yankee Conference. I did not know exactly where the stadium was. I expect to see crowds of people walking toward the stadium. After all, this was their rivalry game. UMass had won last year, but UConn had a pretty good team in 1973. The star, as I remember, was fullback Eric Torkelson4. The conference championship was on the line. The weather was beautiful.

In fact, however, two-thirds of the seat were empty. Very few students showed up. The closest people to me were a guy and his young son. UConn won 28-7 and won the conference championship.

I also tried to play a little flag football. I bought some cleats at G. Fox in downtown Hartford. Norm Newfield was on a team in New Britain. Tom Herget and I went to their tryouts. I played pretty well; I caught every pass that I got a hand on. However, they were looking for blockers and rushers, and I did not fit their plans. Tom did.

I went to several of their games. Once I ended up sitting with Mel, Tom’s girlfriend at the time. I soon discovered that she knew surprising little about football. I explained about the first-down yardage markers and what Tom’s role was on every play. I was just mansplaining, but she seemed to appreciate it.

I played in one pickup game with Tom and some of his acquaintances. It might have been on a field near Batchelder School. Because no one could guard me when I wore my cleats, I had to take them off and play in sneakers.

I watched college football on television every Saturday. In those days I could even bear to watch when Michigan was playing. Jan Pollnow invited me over to his house to watch the Wolverines one Saturday. Michigan won easily. The Big Ten was then better known as the Big Two and the Little Eight.

I felt a little uneasy at his house, as I did the time in Romulus, NY, when the lieutenant in the Intelligence Office had me over for dinner.

Tennis: I brought my tennis racket with me from KC, and I actually played one game of tennis. It was on Saturday, August 18, 1973. My opponent was Jim Kreidler. I was “under the weather” from overindulgence on my twenty-fifth birthday the night before. Nevertheless, I was ahead in the match by a game or two when Jim twisted his ankle.

He wanted to quit. I argued that we should continue the match. I would not require him to stand on his ankle. He could just sit there and wave at the ball with his racket. I would retrieve all the shots on both sides of the net. We could probably finish in a half hour or less.

He stubbornly refused this most generous offer. So, I fear that I must report that I have never actually won a tennis match.

Bowling: At least once I went duckpin bowling with Tom Corcoran and Patti Lewonczyk. It does not feel at all like tenpin bowling, and I have no idea what it takes to be a good duckpin bowler. It seemed like you just grabbed any old ball and let it fly.

On TV I also watched candlepin bowling from Springfield. In this version you get three shots, not two, and they do not sweep away the toppled pins until the third ball has been rolled. So, you can use your “wood” to help pick up spares. I never tried this version.

1. Norm is in CCSU’s Hall of Fame. His page is here. In 2021 his FaceBook page says that he lives in Winsted, CT.

2. Dick Howser died in 1987 of a brain tumor only two years after managing the World Series winners and one year after managing the winners of the All-Star game.

3. Schaefer was a popular beer in the northeast in the seventies. Its slogan was “Schaefer is the one beer to have if you’re having more than one.” No one that I knew liked it. We reformulated it to “Schaefer is the one beer to have if you’ve alreadh had more than one.”

4. Torkelson, although not drafted until the eleventh round, played seven seasons for the Green Bay Packers.