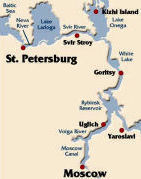

Quite a few people must have elected to skip the Peterhof[1] tour, even though it was the only activity offered on Thursday morning. Only five buses were scheduled to go to Peterhof, which is approximately as far east of the city as Pushkin is south. It is on the Gulf of Finland. We boarded good old bus #45 with Polina. Almost as soon as Pavel had the bus moving, I realized that I had left my billfold lying on the desk in the cabin. It had quite a bit of money in it, too. This realization did nothing to improve my mood. I knew that I would fret about it all morning, and I had no money to spend at Peterhof.

Polina directed our attention to some of the dachas visible near the road. Her main topic for the morning drive was the unbelievable Siege of Leningrad, which lasted for nine hundred days. Hitler’s idea was to storm Kiev, Moscow, and St. Petersburg simultaneously. His troops seized Kiev, but they failed in the other two quests. On September 8, 1941, the Nazis set up a ring eight kilometers from the city. Well over one million people died in the fighting and as a direct result of the siege. During the first winter, which was the coldest ever recorded in northern Russia, people were dying at the astounding rate of thirty thousand per day. Almost all able-bodied men were deployed along the battle lines. Therefore, all of the other responsibilities fell on the women. The only lifeline in the winter was the frozen road across Lake Ladoga. It was called the Road of Life even though it, like nearly all of the city, faced continual bombings throughout the siege. Numerous unexploded bombs were still being discovered in the twenty-first century.The citizens ran out of everything but bread. In February 1942 rations were cut to one-hundred twenty-five grams (approximately a quarter pound!) per day. 45 percent was real bread; the remainder was sawdust and other filler.

Polina related that her great grandmother, like many other parents, sent her child away. At one point she slipped through the lines in order to check up on her daughter. For the rest of her life she thought of herself as a traitor. Polina certainly did not think of her as one. In April of 1943 a truck loaded with onions arrived on the shore of Lake Ladoga. Transporting them to the city was problematic. The spring thaw had left the ice covered with shallow water. Trucks would probably fall through the ice. Horses would not set foot on it because of the water that covered it. There was not enough water to use boats. So, a group of volunteers loaded the onions into packs and set off across the lake on foot. It bears repeating that Lake Ladoga is the largest lake in all of Europe.Three theaters gave performances throughout the siege. Shostakovich, who lived in the city, had an opportunity to leave, but he refused.[2] His Leningrad symphony was performed on August 9, 1942, the same day that Hitler planned to celebrate his victory at the Astoria Hotel. It was broadcast on loudspeakers throughout the city. It became popular throughout the west. Many people were inspired by the symphony and somehow sent encouragement to the people of Leningrad.

In 1943 the Nazis announced that the city of Leningrad was dead. It was not, but many believed it. Mass graves of those who had died had helped prevent the spread of epidemics. Soviet soldiers fought in the swamps and suffered terribly. They had a ration of only fifty grams (!) of bread crumbs per day. The siege was lifted in 1944. The people who survived were too weak to smile. All told twenty-seven million Soviets were killed in the war. Polina said that in Leningrad three bombs were dropped per square meter.[3] In some places there was still – almost seventy years later – too much metal for trees to grow.

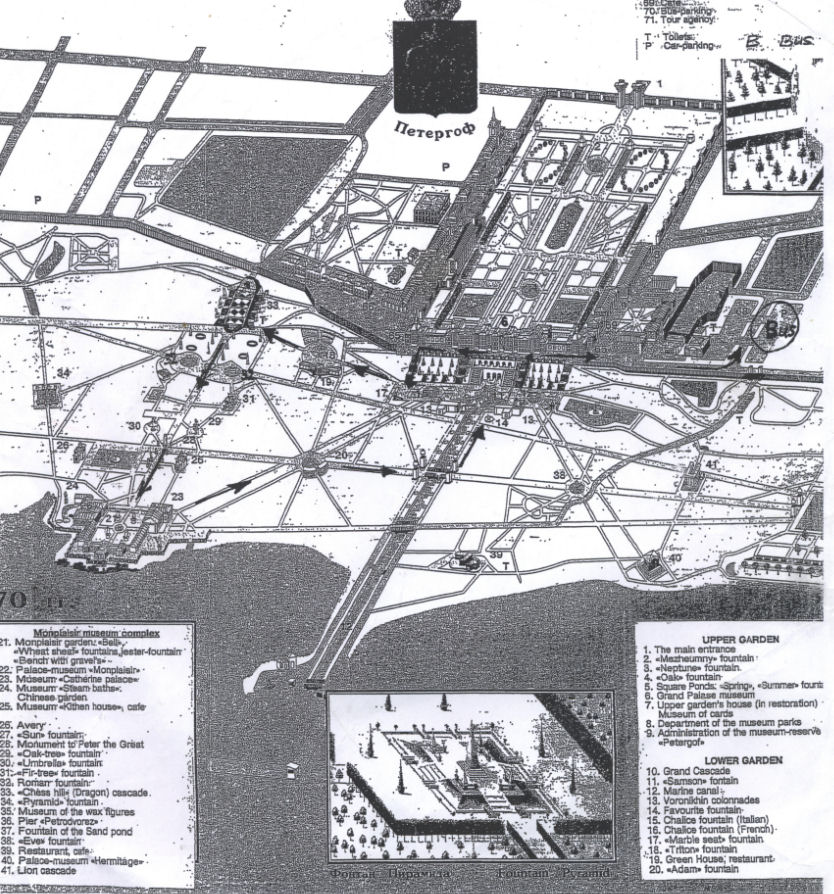

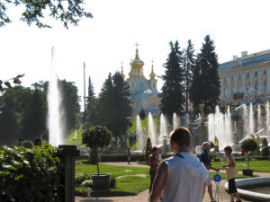

Polina then switched to gears and told us about Peter I and Peterhof. The czar visited Holland in 1696, when he was fourteen. He constructed Peterhof in 1710 in unabashed imitation of Versailles. One major difference was that Peterhof’s fountains used no pumps. All of the work was done by gravity. The major fountains were turned on at eleven o'clock every morning.

Polina read a long list of Peter I’s innovations: the Gregorian calendar, fashion, factories, Russian script, the literary language, newspapers, ships, harbors, canals, roads, and new types of food. He introduced ladies to Russian society, and he instituted schools, the system of ranks, methods of handling complaints, government organization, and travel abroad.Before Peter’s time the only careers opened to women required them to enter the convent. Doctors were not even allowed to treat women except to take their pulse. Peter went so far as to require women to show their shoulders in evening dresses in the manner of the French.

We passed Konstantin’s Palace. President Mevedev lived there when his duties brought him to St. Petersburg. When he was elsewhere, the building was open as a museum.Almost all of the czars married European royalty. A high percentage of their spouses were members of the German aristocracy.

Peter I introduced potatoes to Russia. Peasants would not eat them because of the “eyes,” which they thought meant that the tubers had souls. Instead they ate the berries, which are poisonous. They hated the emperor for forcing them to consume poison. Peter was considered by many of them to be the Antichrist. Russian peasants eschewed potatoes until the twentieth century.

Peter I also introduced smoking. He forced the men of his court to smoke pipes. In 2010 65 percent of Russians smoked, including 37 percent of the women. I think that Polina must have meant that 65 percent of the men smoked.No photographs were allowed inside Peterhof, but the most photogenic attractions were outside anyway.[4]

In the eighteenth century it took twelve hours to travel from the city to Peterhof and back. Nevertheless, Peter often made the trip. More than one hundred bombs fell on Peterhof Palace in World War II. The roof was blown off. In 1950 the government decided to replant the park. In 1964 six rooms of the palace were opened to the public.

Polina led our tour through the palace and provided lots of interesting commentary. The merchant staircase led to the Ballroom. The gilded details there were created by gluing specks of gold. Empress Elizabeth provided the mirrors. The rosy tint in the mirrors was achieved by including a little gold. The ballroom was opened in 2009.Empress Elizabeth once wore a rose in her hair to a party. Another woman in attendance was similarly adorned. Elizabeth had someone cut off all her hair and exiled her to Siberia. A fashion designer who showed some of her dresses to other people met a similar fate. Elizabeth customarily slept from 5 a.m. to 2 p.m. No carriages were allowed in the vicinity during this period. Her fear of death led her to sleep in a different bed every night so that the Grim Reaper could not find her.

Merchants and others with official business were greeted in the Blue Reception room. The Chesme Room showed scenes of the successful 1770 naval battle with Turks. Jacob Philippe Hackaert was hired by Katherine the Great to depict the great Russian naval victory. The Russian admirals did not like his initial efforts. She had the Russian Navy blow up a ship so that the artist could see what it looked like for a ship to be sunk in battle. Twelve of the paintings that he produced were hung in the Chesme Room. Four more were in the Empress’s Study, which also contained a portrait of Katherine’s grandfather and one of the empress herself. Princess Sophia, Peter I’s half-sister, ruled as regent of the co-czars (Ivan V and Peter) for seven years. Then Peter realized that her talents could best be used in the service of the Lord, and he packed her off to the New Maidens’ Convent in Moscow. In the Throne Room Polina told us that Katherine the Great was the first noblewoman in Russia to stop powdering her hair. She also often dressed as a man to show off her thin legs and sometimes sponsored cross-dressing parties. The parties were not popular with the men, or at least most of the men.The portrait of Elizabeth showed her pointing to Peter the Great’s bust to emphasize that he was her father. The apple fell a long way from the tree.

In the Audience Hall Polina talked about some of Elizabeth’s predilections. Count Alexei Razumovsky lived with Elizabeth from the early days of her reign.Katherine the Great feared Elizabeth’s putative daughter, Elizabeth Tarakanova, because she had a better claim to the throne. She assigned Count Orlov the task of arranging a bogus marriage for her in order to get her to Russia. When she was in reach, Katherine imprisoned her. She died in a flood in prison.[5]

The Grand White Ballroom featured authentic porcelain.The Room of Fashion and Graces contained hundreds of portraits, but only six models were used. The paintings were done by Pietro Rotari, Katherine II’s favorite painter. She bought nearly all of his paintings.

There were two Chinese rooms. A German student on a tour brought a vase with him in a box and placed it in one of the rooms. Evidently it was taken by German soldiers, and the student was returning it. The noblewomen in the eighteenth century sometimes put a flea catcher in their bodices. Often vermin established residence in the wigs and garments. Russian nobility bathed every other week. The French bathed once every three months. Queen Elizabeth I of England bathed only three times in her life and found it unpleasant each time. Katherine the Great’s dog Zamira was named after a sultan. A statue of the dog was prominently displayed in one of the rooms. Katherine drank very strong coffee and encouraged everyone to follow her example. Elizabeth spent half of her life looking at her reflection. The “Dressing Room” was a fake boudoir for reception of guests so that she could say that she had no time to prepare herself. Her real boudoir was behind the door. The desk was authentic. Elizabeth used it for signing official papers.Katherine the Great split up her army based on the appearance of the soldiers. She kept the blonde men as her personal bodyguards.

One of the mirrors was deliberately placed too high. Anyone who wanted to use it had to stand on a chair.The Blue Dining Room featured tinted crystal. The technique for coloring crystal was developed in Russia. The crystal items were very valuable.

Porcelain fruit was sometimes mixed in with real fruit on the serving plate. It was a real knee-slapper when someone bit into one and broke his/her teeth.

Polina showed us Levitsky’s portrait of Katherine II burning poppies. It probably was meaningful at the time. Katherine overthrew her husband, Czar Peter III. Nicholas I was the grandson of Katherine II. He liked to venture into town incognito. On one occasion he met a girl, and they hit it off. They arranged for him to meet her parents. Nicholas arrived at their home early and introduced himself using his pseudonym. The girl’s mother told him to get lost because they were expecting the czar.Elizabeth may have been allergic to apples. She strictly forbade consumption of the fruit in her presence. In fact, anyone wishing to meet with her was required to abstain from apples for the entire week before the appointment.

Only six pieces of furniture in Katherine II’s bedroom survived the bombing. The bed was shorter than one would expect. The empress slept half-seated on her doctor’s orders. The toilet chair evidently was one of the six pieces. She kept her crown on a table in front of bed. Peter the Great’s room was all wood and all business. His bible, a globe, and a clock were on display.After the tour, we were allowed about thirty minutes to wander around the lower park before the major fountains were turned on at eleven. We were asked to be back at the bus at11:45.

There were lots of beautiful fountains and pleasant pastoral settings. By 11 a.m. it had become rather crowded. Fast food was available at grills and ice cream places throughout the gardens. Only one restaurant had free bathrooms. This was important information for me, as I had no money at all. If nature called, it would be the free john or a secluded tree for me.

I went all the way down to the water and took photos of the hydrofoils on the Gulf of Finland. I presume that they went to St. Petersburg.

The gardens were spectacular, and they were definitely reminiscent of Versailles. They turned on the fountains right at 11, and the ceremony was accompanied by the St. Petersburg anthem played over the loudspeakers. I tried to get photos from just about every angle of the Samson fountain.After taking about one hundred photos, I made my way through the gauntlet of souvenir vendors toward the bus. I noticed that quite a few of them were selling the kind of military hat that I craved. I suspected that Sue might purchase one for me for my birthday.

I returned to the bus at 11:20. No one was around yet. In a nearby arbor I leaned up against a tree and sat in the shade by myself. I was in a very bad mood. My only friend was a bird, but at least he let me take his photo.

Nearby an Oom-pah band serenaded my birdy buddy and me with an eclectic selection of tunes. I recognized “Chattanooga Choo Choo,” “Blue Moon” (not the arrangement by the Marcels), and “America the Beautiful.” There were also a few unfamiliar ones. The bird did not volunteer whether he recognized them.

At 11:45 Murray and Margaret from Australia were still missing from the bus. It was not a big deal. They arrived about eight or nine minutes late.

On the ride back I concentrated on getting a photo from the bus of a rather spectacular church that I had missed on the way up.Polina talked about more recent times in Russia on the return drive. In the 1920’s the Bolsheviks implemented a crusade against the bourgeoisie. The middle class, such as it was, was eliminated. Possessions of the well-to-do were distributed.

In 2010 there were quite a few billionaires in Russia, but fewer than there were before the economic crash of 2008. Twenty million Russias lived below poverty level, which the government defined as the inability to purchase new winter boots every seven years.

In St. Petersburg the average salary was about forty thousand rubles per month, which equated to approximately one thousand euros per month.The story was much different in Moscow. A strong upper-middle class had emerged in Russia’s largest city. Furthermore, there was no unemployment at all in Moscow.

Individual Russians paid a 13 percent flat tax. Businesses were taxed at the rate of 30 percent. There was also an 18 percent Value Added Tax.

Parking in the Russian cities was nothing short of a nightmare. Polina insisted that the police must see offenders in the act of parking illegally in order to arrest them. Almost no paid parking was available at all. I suspect that what Polina described was so unimaginable that it did not really sink in to most of the people on the bus. Bus #45 returned to the ship a little late. I hurried to cabin #322. My wallet was still on the desk, and nothing was missing. I relaxed a little. I immediately started charging a battery for my camera.

Sue, Patti, and Tom went to one of the other buses for the canal cruise. I headed to bus # 41, which was designated for the tour of the Yusupov (yoo SOO poff) Palace. Nikolai was our driver. Polina and Galina were guides. Galina told us that there were twenty-six of us. We would split into two groups of thirteen each. She would guide one group, and Polina would guide the other.

Galina’s English was intelligible, but she was certainly not the communicator that Polina was. I resolved to make every effort to get myself assigned to Polina’s group. I strongly suspected that everyone from bus #45 had the same idea. My edge was that I was by myself. I located the other lone wolf on the bus. All that I had to do was to lure him into Galina’s group. Galina handed the microphone to Polina to provide background information about the Ysupov Palace. Drat, this might make it more difficult. Once everyone on the bus had heard one of Polina’s presentations, it would doubtless be more difficult to get assigned to her group. Polina informed us that the Yusupov Palace, unlike the other palaces that we had visited, was not a royal palace. Everything in the palace was authentic. It was never destroyed during the war. This seemed very strange to me. Why would the Germans spare such a prominent building in the center of the city during three years of non-stop bombardment? The Yusupov family lived in Russia for five generations. They originally supposedly came from the Middle East. The family settled in the Crimea and then married into Russian nobility during the reign of Ivan IV.Felix Yusupov and his co-conspirators assassinated Rasputin. Despite the title off the movie about him, Rasputin was not mad; he was not even a monk. He almost certainly was not a lover of Empress Alexandra. He was not a magician, or at least he did not belong to the magician’s trade union.

He was born to peasant parents in Siberia in 1869. As a young man he gained a reputation as a preacher and a healer. He believed in God, but he had a dicey relationship with the Russian Church. Sometimes he slightly changed the scriptural texts to make his points. According to Polina, “everyone” who has studied him concluded that he could perform miraculous healing.[6] He was famous for his scandalously immoral behavior in Siberia. He seduced married women, and he stole horses, which, if nothing else, is better than the other way around. Rasputin’s face had noticeable scars.Nicolai drove the bus along the Neva River. He then turned and drove next to St. Isaac’s Cathedral. Polina was not rushed. Nikolai faced slow going in the rather heavy traffic.

At the age of thirty, he was strongly influenced by a priest. After that he wandered from one monastery to another and studied. Alexandra, who had a PhD in philosophy from Oxford, was impressed by his knowledge and reasoning ability. He evidently had a stunning memory.

Rasputin was also known for his mesmerizing glance. He was evidently good at hypnosis. He had light grey eyes. He was best known for his abilities as a healer. He came to St. Petersburg to raise funds for a church early in the twentieth century.

Nicholas II and Alexandra had five children. They hid the fact that their only son, Alexei, was a hemophiliac. Fr. Theophanos introduced Rasputin to Alexandra as “a sinner, the voice of the Russian soil. Since his repentance he is pure.” Alexandra spoke Russian badly. Rasputin allegedly healed Alexei after several hours of prayer. Rasputin gave advice to Czar Nicholas, but, like just about everything else in Rasputin’s life, it is unclear whether the czar followed it. Rasputin was never paid, but he accepted gifts and called Nicholas and Alexandra “daddy” and “mommy.”[7] Lots of Russians suspected that in the period leading up to World War I Alexandra, who was German, and Rasputin influenced Nicholas to be sympathetic to the German cause. Rasputin was in Siberia when Alexei had an accident and was bleeding uncontrollably. When he learned of the problem, Rasputin sent a telegram to the royal family. Against all odds the boy got better. In 1916 Rasputin was hated by nearly everyone in Russia except Nicholas and Alexandra. Felix Yusupov considered it his duty to eliminate Rasputin for the sake of the monarchy.

Katherine II bought the palace in the eighteenth century. In 1830 the Yusupov family acquired it. It had one-hundred fifty-three rooms. In 2010 it was owned and operated by the teachers' trade union. It was not open to the public. Only select groups were allowed to arrange tours. That could explain why it was not mentioned in my guidebook.

In 1887 Felix’s mother, Zenaida, already had a son named Nikolai. She wanted a daughter very badly and was sorely disappointed when Felix was born. She dressed Felix as a girl. He later claimed that this might have explained his sexual orientation. Forty-nine thousand of the fifty-two thousand precious objects in the Yusupov Palace were confiscated by the Bolsheviks in the 1920’s.Inside the palace I had to pay one-hundred fifty rubles for a ticket that allowed me to take photos. I certainly hoped that my camera’s batteries held up. I had, after all, given the camera a pretty good workout in the morning.

I had little trouble getting into Polina’s group. Galina departed first. I – and everyone else from bus #45 – stealthily shuffled backwards as one couple after another followed Galina. I knew that I was safe when the other loner joined them.

In the Red Living Room Polina emphasized that in the eighteenth century they added gold to mirrors to make people look rosy. The same trick was used in hotels.

The chandeliers had one-hundred thirty pendants. They were authentic.

In the Ballroom we were treated to a short concert by a choir of five singers. They seemed very talented to me. Polina said that we would get to listen to many such groups on our trip.

The Banquet Hall’s[8] high rounded ceilings meant that its chandeliers needed to be very light. They were therefore constructed of papier mâché! The Gallery of Arts contained five rooms. Nikolai Yusupov, Felix’s grandfather, collected these pieces as well as most of the art that was later moved to the Hermitage. Imagine that: most of the Hermitage’s priceless collection once belonged to one man. He also collected violins by Stradivarius, lace, buttons, and Star Wars action figures. Zenaida Yusupov was known as a great beauty. Her granddaughter was still alive in 2010 and lived in Greece. For several generations only one male Yusupov per generation had lived to be twenty-six. The family considered it a curse. Zenaida’s husband and his sons were allowed by the czar to use the Yusupov name. Nikolai died on the eve of his twenty-sixth birthday in a duel. The title was therefore passed to Felix. He inherited fifty-three estates, fifty-two factories, four palaces, and the kitchen sink. The angel depicted in the Small Rotunda Room seemed to resemble the girl who had died. I wrote this down, but I no longer remember who the girl was.Nicholas Romanov, the grandson of Czar Nicholas I, fell in love with a young American woman named Fanny Lear.[9] The Romanovs had him declared insane and confined him in Siberia.[10] He was told that she had rejected him. He died in exile from his family and his sweetheart.

No photos of the temporary collection were allowed.I was shocked and delighted to learn that the palace included an opera theater.[11] UNESCO had designated it as a world treasure. Polina reported that Felix, who had a beautiful voice, actually performed in public six times as a female opera singer. In his last concert friends of the family recognized some of the singer’s jewelry. For some reason his father was furious at him.

I would really liked to have had the opportunity to attend an opera in an intimate theater like this one. What a great life these people must have had! I snuck a peak at the orchestra pit and took a quick photo of it. Polina said that the stage was as deep as the seating area. I bet that you could stage an opera like Cosí fann tutte or Don Pasquale here.

The Yusupov family was in charge of the coronations of the czars. We saw a photo of Prince Philip of England and his wife, What’s-her-name.Felix married Irina, the only niece of Czar Nicholas II.

At this point Polina’s presentation was interrupted by the unmistakable sound of an auto accident that evidently occurred right outside the palace.

We then joined back up with Galina’s group, and Polina escorted all twenty-six of us through the rooms that were given to Felix. They were not nearly as elegant as the rest of the palace, but they were very tricky. One very small room that we entered had eight doors and no walls. Every door contained a mirror.Polina did a great job of bringing the rest of the story to life. On December 16, 1916, a group of plotters – Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich (the Czar’s cousin), Vladimir Purishkevich (a member of the Duma), Lieutenant Sukhotin (a young officer), and Dr. Lazavert – met in Felix’s rooms. The plan was to lure Rasputin to Yusupov palace by using the lovely Irina as bait. Dr. Lazavert made a concoction of cyanide. Colonel Mustardsky was in the conservatory with the wrench.

Rasputin accepted the invitation, and Felix urged him to sit for a minute and enjoy a drink and a slice of cake because, he said, Irina was busy entertaining a party of guests downstairs. She would allegedly join them shortly. The other conspirators made party sounds in the room below, and they played the phonograph. They stupidly played “Yankee Doodle” over and over, and this may have tipped off Rasputin. After two hours Rasputin told Felix that he did not feel well or perhaps he was just thirsty. He drank some wine, and then said that he felt better; he must have just been thirsty.

Felix panicked. He went downstairs and got a pistol. He went back upstairs and shot Rasputin twice. He was certain that he was dead, but Rasputin got up and tried to strangle him. This was more than Felix could bear.

He broke free from Rasputin’s grasp and went downstairs, but he was too upset even to explain what happened. The others came up, and discovered that Rasputin was gone. They found him outside. One of the other guys shot him twice more. Felix told a policeman who heard the shot that someone was drunk and accidentally shot the dog.The conspirators wrapped Rasputin’s body in a bear skin rug. They threw him in a hole in the ice in the Malaya Neva River. One shoe came off in the process. His corpse was later found beneath the ice with water in the lungs. This undoubtedly meant that Rasputin was still alive when he entered the water.

In 2010 one political party was campaigning to canonize Rasputin.[12] He reportedly had made a prediction that he would call the Romanovs to join him a year and a half after his death. They were executed exactly eighteen months after Rasputin’s murder.Felix was banished from Russia for his part in the murder.[13] He and Irina moved to Paris, where he wrote a very popular book about Rasputin’s demise. Rasputin’s daughter also wrote a book that challenged many of Felix’s claims.

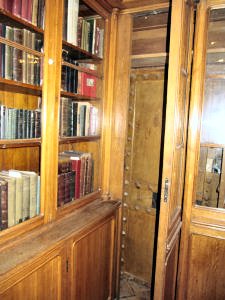

The Yusupov Palace contained three thousand books in its library. Gems and jewels were found hidden behind the shelves in a secret compartment.

Polina demonstrated an interesting aspect of the Billiard Room. Clay pots within one of the walls amplified the sound so that Polina sounded louder even as she walked away from us.

One of the rooms had a distinctly Arabic flavor. The first Yusupov was supposedly a son-in-law of Mohammed the Prophet.Rasputin’s daughter Matriona immigrated to the United States and wrote her memoir at the age of eighty. Rasputin had three children – two daughters and a son – by his wife in Siberia. He was definitely not popular there. Rasputin’s son died in a concentration camp.

When the tour ended, I rushed over to the small bookstore in the lobby and bought a book in Russian about the palace for two hundred rubles. The versions in other languages cost four-hundred seventy rubles. Since it was mostly photographs, I figured that I could translate the text without too much difficulty. Also, I am very cheap.

The tour of the Yusupov Palace clearly stood out as the highlight of the trip for me. I did not know how closely Polina’s account jibed with what actually happened to Rasputin. I did not really care. It was meaningful, vivid, and exciting.

After our bus returned to the ship, I learned from Tom how much he had hated the canal excursion. Evidently they got in Gennady’s group. Gennady was from Moscow, so he was prohibited from guiding tours in St. Petersburg. A native of St. Petersburg who was quite difficult to understand guided the tour for his group. To make it worse, her voice was evidently very grating. Sue said that she did not enjoy it much either.

Just before the Captain’s reception the ship set sail for our next destination, Mandrogi.

I noticed several times that there appeared to be gravel operations of some kind up and down the shore of the Neva.

Before supper there was a short reception in the Sky Lounge. There was free champaign, and we got to meet the captain and all of the high-level staff members. We also were introduced to all six tour guides.

We ate supper with Elizabeth and Susan McCord. Patti skipped supper. I did not record what we had to eat, but from looking at my pictures and Sue’s videos I deduced that it was probably halibut. Susan M. had bought some small pictures somewhere with cryptic writing on them. Someone told her that the writing was in Latin. It was actually Russian, but maybe not modern Russian. I repaired to our cabin to fetch my dictionary, and I tried to translate them for her. I could only make out a few words. When we got back to the cabin, Sue presented me with a military hat with a visor that she had bought for me as an early birthday present. She got it at the stand of one of the vendors in Peterhof. It was just what I wanted, but it was much too small for my oversized cranium. It actually popped right off of my head no matter how I tried to put it on. She said that she might be able to let out the band.

St. Petersburg was great, but it was both physically and mentally exhausting. We needed a break.

[1] Peterhof is written as Петергоф in Russian. This is consistent with the tendency that I had previously noticed to transliterate the English letter h as г, the Russian g. I have never understood this.

[2] He and his family actually evacuated the city in October 1941, three weeks into the siege.

[3] I must have misinterpreted what Polina said. That amounts to roughly 7.77 million bombs per square mile.

[4] It was also easy to find plenty of excellent photos on the Internet.

[5] Or so the legend goes. When we toured the Tretyakov Gallery, they told us that she actually died of tuberculosis.

[6] I bet that The Amazing Randi would disagree with this conclusion.

[7] Rasputin evidently shared with George W. Bush the extremely annoying habit of calling everyone by a pet name of his own device. He called Felix Yusupov “little one.”

[8] Shortly after we returned to Connecticut, PBS broadcast a show in which Renée Fleming and Dmitri Hvorostovsky sang duets in this room.

[9] Her real name was Harriet Blackford from Philadelphia. She wrote a popular book about this and her other adventures abroad.