Nothing was scheduled until Polina’s Russian history lecture at 10:15. I went up to the Sun Deck and found it very windy up there. I already was wearing my nylon warm-ups on, but I felt compelled to return to the cabin to retrieve my jacket. I stopped by the coffee stand and got a cappuccino in a cardboard cup from the machines. I also took a lid, but it did not fit very well. I ended up spilling coffee all over my nylon pants. They were nearly water-proof; it was not a big deal.

The ship passed through a lock and was incredibly high above the trees. I had a very hard time understanding how this was possible. In my world land was never lower than water.

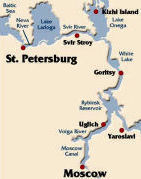

The ship approached White Lake, which was famous for being almost perfectly round. We were told that a dilapidated church was the boundary.

At a little after ten I ascended to the Sky Bar to attend Polina’s lecture on Russian history from 1917 to 1985. Her basic theme was that Russia had an “unpredictable past.” She emphasized that the facts that she presented were based on the best information currently available.1917 brought two revolutions. In the first the liberals persuaded the hapless Czar Nicholas II to abdicate and then abolished the monarchy and established a democracy. Then on October 25 of the same year Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (a.k.a. Lenin) and the Bolsheviks took over on behalf of some of the nobles, whom they ousted from power in short order. The Bolsheviks appealed to two dreams of the Russian people: the dream of land and the dream of peace.

The government immediately seized land from the wealthy landowners and gave it not to the people but to the state. It negotiated a peace agreement with Germany that was disastrous to the Russian economy. It lost 40 percent of its industry as a concession to Germany. The ruble was devalued twenty times. A great deal of money had to be spent to keep fighting the White Army, which was intent on restoring the monarchy. The country was invaded by Japan, the United States, Great Britain, and Canada. There was no mention in any of my history books that the Americans had invaded a country that was not even involved in the war, but it definitely did happen.

The White Army tried to force the peasants to abandon their new land and to fight in World War I on the side of Germany.[1] This made the monarchists extremely unpopular. Nicholas and Alexandra were even more despised in Russia than the Bolsheviks. In the end the Red Army won the civil war.The country was renamed the Soviet Union in 1922. It was in terrible shape as a result of years of war, drought, and revolution. To make it worse, a typhus epidemic lasted for two years. Eighty-five percent of the country was illiterate, and the ruble was worthless.

The catchphrase of the day was “militant communism.” The size of the army was increased by a factor of ten. Three goals were promoted: industrialization, collectivization, and cultural revolution. Most of the harvest was expropriated from the farmers and exported to other countries. Grain paid for machinery, largely from Germany, even though the people were starving. By 1935 Russia was heavily industrialized. Six hundred plants were built every year. Only the United States was more heavily industrialized. The villages paid dearly for the growth of the cities.

Lenin did not die until 1924, but he had suffered four debilitating strokes between 1922 and 1924. Stalin had for all intents been in charge for years. During Lenin’s convalescence Stalin ordered a special edition of Pravda printed every day just for Lenin so that he only learned what Stalin wanted him to know.

Despite the deep crisis in light industry and agriculture, industrial growth continued at 15 per cent per annum. Collectivization had a perverse effect on agriculture. The inefficient farmers welcomed collectivization because it saved them from failure. The most successful farmers, the kulaks, fought against it.Churchill reported that Stalin had confided to him that ten million people had been eliminated as enemies of the state in Russia. Two and a half million were forced to collectivize. When Stalin published an article that said that collectivization was voluntary, 75 percent tried to withdraw. Stalin changed his tune.

Lenin’s last will denounced Stalin. Lenin said that Leon Trotsky was the most capable of the Bolsheviks, but he was too self-assured. Trotsky quarreled with Stalin in 1929 and fled to Mexico. He was killed in 1940 with an ice axe by Ramón Mercader, a Spanish Communist who was given a gold medal in Russia for the deed.

Stalin’s motto was “Communism in a Separately Taken Country.” The Russian secret police was initiated by Felix Dzerzhinsky, a former Jesuit.[2] What was first known as the Cheka evolved into the KGB. Dzerzhinsky died in 1929. He gave a speech, took a drink of water, and collapsed dead. Lavrenty Beria took over. After Stalin’s death he was the last “public enemy.”In 1937 you could be executed for planning to leave Russia. A sentence of ten years could be levied for not reporting someone’s plans to leave the country. Sufficient evidence of hoarding food was the very lack of food. Gulag camps were established. Polina also said something about fifty-two million people, but I did not record the details.

Under Stalin the clergy had no right to property. By 1937 when all the taxes were included, the total levy on the clergy was 110 percent of earnings! In 1922 alone eight thousand priests were executed. All told, about two-hundred thousand members of the clergy met the same fate.

Germany was friendly to Russia from 1918 to 1941. Stalin and Hitler concluded the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in 1939. It called for mutual non-aggression for ten years, but Hitler’s army invaded Russia on June 22, 1941. Stalin was evidently shocked into catatonia by Hitler’s double-dealing. If you can’t trust a fellow moustache afficionado, whom can you trust? Molotov signed the treaty with Hitler, but he was also friendly with Roosevelt and Churchill.

Germany had more troops than Russia and was much better prepared in 1941. The Nazis destroyed 75 percent of the Russian planes in a single day. After one year 50 percent of the population was behind German lines. Hitler sent an astonishing 1.2 million troops to assault Moscow. They approached within twenty-seven kilometers of Red Square. The battle for the city lasted through the winter of 1941-42.

The siege of Leningrad lasted from September 8, 1941 through January 27, 1944. Russia was subject to total annihilation, so the Russians would not give up. Hitler’s instructions were not to let anyone survive.

Polina showed shocking photos of the same woman in Leningrad in 1941, 1942, and 1943. She appeared to have aged decades, not years during the siege. Polina shot the photos herself in the Military Museum in Moscow. She said that we should not miss the Military Museum. Uh, oh. I did not sign up for that tour, and I had heard that it was already full.

Everyone who could possibly fight enlisted in the Russian army after the German invasion. This was accompanied by a huge increase in production of arms in factories. Nearly all of the employees were women.

The Battle for Stalingrad lasted six and a half months. Germany lost 1.5 million in the battle. Russia lost 1.2 million. Nearly everyone in Russia had a friend or relative in the battle. The German Field Marshal finally surrendered in February of 1943 and thereafter Germany was in retreat.

According to Polina, Russia lost twenty-seven million people to the war. That is unquestionably a staggering number, but even more astounding to me was the fact that 1,710 cities were annihilated.

Marshall Zhukov led the Soviet army and became a national hero. Stalin also became tremendously popular. Before the war the Soviet Union had had relations with twenty-six countries. Afterwards the figure doubled.

Life expectancy and many other measures of well-being improved dramatically after the war. In 1949 Russia developed its first nuclear bomb.

Khrushchev, who became First Secretary in 1953, was not as harsh as Stalin. In 1959 he brought back corn from United States and forced farmers to grow it. It would not grow in the Russian climate, and it depleted the land. In 1961 the missile crisis erupted over Soviet missiles in Cuba and, according to Polina, American missiles in Turkey. Khrushchev built flats for millions of people and allowed them to live in them for free. 1954 brought the first nuclear icebreaker and the first nuclear power plant. Sputnik, the first satellite, was launched in 1957. Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space in 1961. Two years later came the first female cosmonaut. It was morning in the Soviet Union.

Khrushchev spoke openly of Stalin’s crimes. He gave amnesty to one million political prisoners.Khrushchev was ousted in 1964 by Brezhnev. Russians ironically noted that Brezhnev tried establish a cult of personality with no personality. He was nicknamed the Christmas tree because of all of the medals that he wore on his chest. He presided over twenty years of stagnation. Russia even imported grain during his administration.

Russia sent tanks into Prague in 1968 and for some reason invaded Afghanistan in 1979. Russia lost four hundred thousand[3] troops in Afghanistan.

The theme of the 1980’s was “Develop socialism.” Nineteen million people belonged to the Communist party, but many no longer believed in the socialist ideal.

A joke about Brezhnev’s legendary wooden delivery when reading his speaches: In preparation for the 1980 Olympics Brezhnev was practicing reading his welcoming address. He began with Oh Oh Oh Oh Oh. They had to explain to him that what he was reading were the Olympic rings.

Brezhnev was succeeded by Andropov and Chernenko, two old men who died within a year of taking office. Gorbachev, in contrast, was young and charismatic when he took office in 1988. He was very popular at the outset, but he ended up hated by nearly everyone.

It was no surprise to me that Polina’s presentation was both powerful and informative. Anyone in attendance who was not rocked out of his/her comfort zone was either not paying attention or was criminally insensitive.

We were a little late for lunch, and, since there were no empty tables, we joined a British couple at a table for six. They left the table just after we arrived. I had the shchee (щи), which is cabbage soup, and turkey steak with rice. The former was surprisingly good, and the latter was surprisingly bland.We landed in Goritzy at 12:45. At least that is what they told us. I saw a large empty building that was evidently a bar, some colorful wooden boats of all shapes and sizes, a long boardwalk to the parking lot, and a gift shop. That was all. Our destination was the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery, which was a few miles from the pier.

The local guide was named Andrei. His English was a little halting, but it was generally understandable. Unfortunately he was apparently trying to develop a second (or maybe third) career as a comedian.The bus ride took fifteen or twenty minutes. We learned that 1.2 million people resided in the area known as Northern Russia. The Slavs came from Novgorod and mixed with the local people. Andrei told us what the latter were called, but I did not get it down. The main industry was wood: pine, spruce, aspen, and birch. Most of this was exported for furniture. A lot was also exported to Finland for paper. The lowest quality wood was used for heating.

The capital of the district was Kirillov, which was founded by the fourteenth-century Saint Cyril.[4] We passed a national park, which I think Andrei identified as Russia North. It contained many animals – bears, foxes, eagles, swans, geese, snakes, etc. The area was also abundant in freshwater fish, trees, and lady’s slippers. The name of the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery was derived from a combination of St. Cyril and the Russian name for the White Lake. Cyril came to the area because either the Blessed Virgin Mary or the dukes in Moscow sent him. There were competing legends. The site was on two important trade routes. Cyril personally founded the monastery, which at one time[5] was the largest Christian monastery in the world, in 1397. The fortifications were built as a defense against the Swedes.In 2010 the population of the town of Kirillov was nine thousand. The lake abutting the monastery was full of fish. Ice fishing was very popular.

The monastery had four purposes. It served as a fort, provided education, was the center for trade, and was the place that people were imprisoned. The monks kept a small army. Patriarch Nikon was imprisoned there in the seventeenth century. He was exiled from Moscow for fifteen years.

The monastery once had a twenty-two-ton bell that could be heard eighteen miles away, but the bell tower had long been empty. Czar Peter I confiscated the bells for cannons and took the carpenters to help in St. Petersburg. Katherine II was the biggest enemy of the monks. World War II took away any remaining scrap metal. The father-superior’s building was renovated sixteen times in two centuries. No photos were allowed inside. Lots of icons were on display there, but looking at icons was beginning to be tiresome. A lady named Tonya was on the lookout for anyone wielding a camera. One exhibit featured St. Cyril’s hat and coat, which dated to the fourteenth century. St. Cyril died in 1427 at the age of 93.Andrei said that the monks ate no meat, and drank no vodka or beer. No wonder there were so few of them.

The Room of Donations contained precious items that had been given to the monks. In the seventeenth century one of the czars donated elaborate doors.

The monastery boasted two thousand hand-made books. I am not sure why we were supposed to be impressed by this. All books before the sixteenth century were hand-made, and most of them were written by monks. One of them here was a cookbook that contained the aphorism “No bread is better than no fish.”In Andrei’s view, the Time of Troubles was a Russian civil war. The attack on the monastery was resisted by the monks' troops. They used muskets that could be fired twice every seven minutes and pistols. The most effective weapons were big tacks laid in the field to cripple the enemy’s horses. They were called “evil garlic” or “flower of lameness” (French). The people who made and dispersed them were therefore called florists.

We saw the throne of Patriarch Nikon. Katherine II hated monks and priests. She confiscated all their land and trade rights. Three monks were at the monastery when the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917. Only four monks and two novices resided in the monastery in 2010. The Russian people loved Katherine the Great and called her “Mother Katherine.” All Russians paid a tax of only 1 percent per year.[6] Many Europeans came to Russia.An iconostasis generally had five tiers. Some of the icons had obvious mistakes. In one a horse was shown in a biblical scene instead of donkey because donkeys were unknown in Russia. In another a palm tree looks more like a pine tree. Most of the gold and silver used in the ornamentation came from Latin America through Spain.

In the seventeenth century the Russian Church banned icons that showed God as a person. Nevertheless, some have survived.

We saw ornate bishop’s vestments. The bishops wore red only on Easter.An icon showed the biography of St. Katherine. I could not find a Russian saint with that name. It surely could not be Katherine of Siena; she lived after the Great Schism. I think that it must have referred to St. Katherine of Alexandria.

Andrei went to school in the San Francisco area. The school apparently began with an H, but for some reason he was unable to pronounce it. This seemed weird. He might have been making a joke.

At one point we heard rain outside. Andrei was elated at the prospect of a little precipitation. Evidently the area had received none in many weeks.

Andrei rushed outside and retrieved some colt’s foot, which he said was called “mother and step-mother” One side was soft; the other was rough. He then told a joke. One guy said to another, “You know, my mother-in-law is an angel.” The other replied, “You are lucky; mine is still alive.”

Embroidery was strictly a female business. It took two to three weeks to perfect each square inch. Many ladies went blind as a result.

The tour of the museum ended with a compulsory stop in the gift shop. I did not mind this too much, per se, but I wish that there had been a place to which those of us who had no interest in buying any of this stuff could have gone. All that I was interested in was a place to sit down.I feel compelled to register another complaint about not being able to take photos inside the museum. I guess that the monastery must have relied on the gift shop to finance the operation, but I was not about to shell out hundreds of rubles for pictures of what appeared to be third-rate items. As a result, I came away with nothing but photos of the very mundane exteriors of the monastery. There are plenty of photos of the icons on the web.

We went over to the lake that adjoined the monastery. Andrei said that it was very deep, and the legend held that a dip in it would make anyone ten years younger. Some kids were swimming there. For all I knew, they might have been octogenarians when they woke up this morning.

In the winter the ice was two and a half feet thick. Andrei said that the locals used Swedish tools and Shakespeare fishing rods.

We then went into a room with benches and a very high ceiling. We listened to a four-man choir perform songs from the nineteenth century. The acoustics were very good. I was especially impressed with the bass.

In 2010 the government was reportedly spending one million rubles per year on restoration of the monastery. Putin had allegedly pledged more, but they had not seen it.

Back on the bus Andrei told an inane story about being able to calculate the number of angels in heaven using scripture. He also claimed that before the revolution rye beer was more popular than vodka. The natives celebrated Christmas and New Years twice a year. They closed the schools when the temperature fell below -30 Centigrade, which is only -22 Fahrenheit. What a bunch of sissies. Next they will probably ask for heated classrooms.The farmers in the area grew barley, oats, flax, and potatoes. A favorite activity was harvesting some of the thirty-two different varieties of mushrooms to be found in the forests. According to Andrei, agriculture was destroyed by Yeltsin’s policies.

This was a dreary day. The monastery was not very attractive, and the scenery was not very interesting either. I was probably too hard on Andrei. He was very enthusiastic, and he provided quite a bit of information. I could not pinpoint what he should have done differently.

From the deck of the ship I watched Gennady march up to the gift shop at the harbor to herd the last stragglers back to the ship so that we could leave Goritzy on time.

I went to Konstantin’s port talk at 7:15. He said that the River Sheksna became shorter when they put in the artificial lake. The city of Cherepovets was famous for its large chemical factory. Ten years earlier the Viking ships asked all passengers to seal the windows of their cabins when they went by.Everyone either stands or kneels during Russian Orthodox church services. The interiors were much smaller than I expected.

Yaroslavl, our next destination, was founded in 1010 (or thereabouts) by Yaroslav the Wise. It would therefore be celebrating its millennium while were there. The famous Church of Elijah the Prophet was built by a rich merchant in hopes of impressing his friends and rivals. Yaroslavl was famous for its honey.

Supper was not served until 7:30. It was an “international dinner,” but I did not record any details about it, and I did not take a photo of the menu. It is obvious from one of the photos that the ship was passing through a lock while we dined.

I must have had a reason for agreeing to shell out fifteen units to attend the Vodka Tasting, but at this writing it has escaped my recollection. Philipp, the hotel manager, was in charge. He gave each of us a sheet of paper with more than anyone would ever want to know about vodka.

The Sky Bar was nearly full. There were even some spectators sitting on bar stools.

A guy named Murray joined Tom and me at our table. Murray was about my age and was formerly the editor of the publication Chain Store Age. He told us that he had retired a couple of years earlier when the economy looked really bleak. His magazine had to lay off a good number of people. I was familiar with the publication. When I told him what our company did, he said that if he were still working, he would have had a contract with him and would have persuaded me to buy some advertising space before the end of the Vodka Tasting. Maybe yes, maybe no. We bought an ad in a magazine exactly once and vowed never to do it again.Philipp emphasized to us that vodka should always be drunk with water on the side, and it should never be consumed on an empty stomach. Therefore, an impressive buffet was laid out on a table in the Sky Bar, and we all filled up our plates with munchies. The first bottle was called Diplomat, a brand that has been around since 1721. Aivar showed us how to drink a shot balanced on the elbow. Philipp insisted that other countries drank more vodka than Russia, but he did not name any. The second one was 5-Star (Pyatizvesdnaya – пятизвездная). Philipp said that Kristall was the most famous distiller and distributor of vodka in Russia. Gorbachev had taxed vodka heavily and inadvertently created a huge black market in dangerous vodka.Russians also love tea. They drink two-hundred fifty liters of tea per year.

Vodka should always be drunk ice cold, and it always should be accompanied by food. Shot glasses should be frozen. Russians never mix vodka with anything.

The third round of the tasting was Smirnoff. The company was started in 1860 and has won several gold medals.

The fourth was a black currant-flavored Absolut. Russian menus show weight in grams. Vodka is drunk in tumblers, not shot glasses.The fifth was Nemiroff, which was flavored with peppers and honey.

The last one was Russian Standard (Стандарт). After it was served, they cut the fish, and some of us tried a little. I thought that it tasted a lot better than the vodka.At this point I knew that I was probably going to be sick. I have never been much of a drinker. I just hoped that I could make it to the cabin.

I made it to #322 without a proplem, but for a while I could not find my key card.[7] When I located it, I successfully inserted it in the door and went inside. Sue was watching the old James Bond movie, From Russia with Love on television. I up-chucked many times. In between I found the sound of the movie intolerably annoying, and I asked her to turn it off. She did, but she complained that she found the sound of my retching even more annoying. After I was pretty sure that I had thrown up everything that I had consumed as well as the meals for the next day or two, she gave me some Alka-Seltzer. I went to sleep immediately and had no more problems.

I will say this for Russian vodka; it tastes a little better on the way down than on the way up. If I never see another bottle, that will be fine with me.

[1] This is what I wrote in my notes, but I am pretty sure that if anything, the White Army fought against the Germans.

[2] I could find no evidence of him ever being ordained. As a youngster he seemed to have aspired to join the Jesuit order, but I don’t think that he ever did.

[3] This is what I wrote down, but it is wrong. Less than fourteen thousand were killed, but hundreds of thousands contracted diseases in Afghanistan.

[4] This is not the famous St. Cyril, for whom the Cyrillic alphabet is named. He and his brother St. Methodius lived five centuries earlier and never visited Russia.