Our hosts in Chada Camp had no intention of short-changing us on the last day. Our one-hour flight from Katavi's airstrip to the one just north of Mahale Mountains National Park was scheduled for 12:30. A final game drive was to begin right after breakfast. The game drive would end at the airstrip.

I felt pretty good, but I was still worried about that flight. I limited my consumption at the morning meal to cereal and toast. The latter had the consistency of New Hampshire granite.

Before the game drive we were required to have all of our bags packed so that they could be at the airstrip when we arrived after the game drive. I extracted from my duffel the plastic bag that I had originally used to hold electrical converters, cables, and other non-clothes items, and put it in my pocket.

I took care of the tip for the staff before we left camp. If there was a book for comments, I did not see it.

The five New Englanders piled into Molil's Land Rover for the last game drive. Almost immediately Molil spotted a brown snake eagle overhead, but I was unable to photograph it. We spent a good deal of time watching a bull elephant. The first clue to his gender was the fact that he was by himself.Female elephants are generally quite social; males are loners. The shape of the back was another clue, but the difference was not obvious to me. It was easier to tell from the back, but only if you knew what you were looking for. On females the area under the tail was more "boxed off."

We then watched a group of two males and one female giraffe. I took several pretty good shots, including one outstanding one of a long purple tongue. With binoculars it was quite easy to tell males from female giraffes. The horns on a female were hairy and rounded. In contrast, the male's horns were flatter and completely bald.

We saw a white-crested helmeted shrike and a greater blue-eared starling, but I was unable or maybe unwilling to photograph either one of them.

Molil identified a robin by its call. My notes include no indication as to which species it belonged to.

Hippos can be very noisy. We heard some in the distance. Jeff called them the "trombone section."

When we approached a beautiful green tree on the side of the road, Molil identified it as a mahogany.

Molil evidently knew that a pride of lions liked to hang out under a tamarind tree near the huge savanna, and he took us there near the end of the game drive. He told us that there were nine lions in the pride. In the flat savanna over one hundred yards away a group of zebras walked slowly in full view of the lions.

The other Chada vehicle, in which rode Matt, Hannah, Kirsten, Jan, and their guide, was already parked near the lions when we arrived.

We could clearly see a few of the lions, but never more than six or seven at a time. They were lying placidly on a small hill beneath a tamarind tree. There may have been some on the other side of the hill that were just out of our view. The lions that we could see kept their eyes on the zebras, but they never gave any indication that they were much interested in disturbing their siesta for a run at them.

At some point we were joined by a third vehicle that was jam-packed with Japanese tourists. I could not see them very well, but Tom later told me that he saw an astounding number of people in the car, which was air-conditioned. Of course, that meant that their view of the lions and everything else was impeded by the windows.

I do not think that these people were staying in the park. They seemed to be in transit. I suppose that it would not be obvious that this would not be a good way to spend a holiday. Driving in Tanzania was never a pleasant experience. These people did not even have a four-wheel drive car. Furthermore, Tanzania was a big country. If you were interested in diverse experiences, the best way to do it was to take the bush flights between the National Parks. However, don't forget to bring plastic bags; the air sickness bags are unreliable.

Molil eventually needed to back up the vehicle. We almost ran over an African hare that was lying flat on the ground and had exerted no effort to avoid the Land Rover's wheels. It must have been sick or injured. The lions showed no interested in it.

At the end of the viewing Molil pulled the Land Rover up a couple of car lengths so that we could see the huge male sleeping between some palm bushes. Our view was obstructed; we could only see the hindquarters clearly. We had to guess what the rest of him looked like. That was a shame; the full-grown males do not even look like they are the same species as the females and juveniles. They are much more massive in every dimension and, of course, their manes are quite distinctive. Even this one's coloring seemed markedly different.

Molil drove us to the airstrip, where we exchanged goodbyes and best wishes. All of our guides were outstanding, but for some reason I liked Molil the best. To think that he grew up in the separatist Maasai culture, and yet as a young man he was earning his living by communicating with and educating strangers from all over the world. Moreover, he was doing his part to maintain the integrity of something very important. His unique story touched something within me.

Our plane was pretty close to on time. Once again no one weighed the luggage. I was glad that I did not bother to wear my boots. The plane already had four passengers, the two couples whom we would meet when we reached Mahale. Rodd, Amy, Scott, and Shelly were all from Sacramento, CA.

I sat in the back row. Before the plane moved an inch I removed the air-sickness bag from the seat pocket, and the plastic bag from my jacket pocket. I then placed both items on my lap and donned my sleep mask.

It was only a forty-five minute flight, but the wind was blowing, and the flight path took the Cessna over the northeast corner of the Mahale Mountains. It was much bumpier than the flight from Kogatende to Tabora. The others were all talking about how scary the landing was. The plane reportedly cleared the last mountain by only a few feet, and from that height the runway, which ended at the edge of Lake Tanganyika, appeared very short.

I saw only the back of my sleep mask. My mind's eye was focused on a pig-pile of lions snoozing on one another.

The airstrip in Mahale was nicer than the other two. The toilet was relatively civilized, and there was a comfortable banda in which to sit at tables in the shade. It also had an office in which we had to check in. We had to register with an official there, just as we had been required to fill in our names and other information on a register at the other airstrips. When I filled in my name, I glanced at the age column. My entry was by far the highest number on the page. I was just happy to have made this trip while I still could. Having survived the flight without upchucking, I felt invincible.

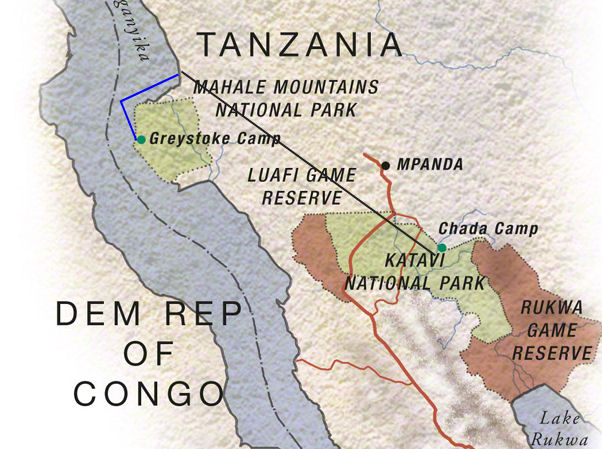

I took a photo of the map of the National Park that was on the wall. It appeared to be intended to be handed out to tourists, but the only other copy that I saw was in a book in Greystoke Lodge.[1] I could not find an image of it on the Internet either.

Before long the dhow arrived. While we waited, our luggage was transported down to the lake in what could best be described as a very large wheelbarrow. Our plane also brought a few boxes of supplies for the camp. All of this was eventually loaded onto the dhow.

All eleven of us boarded the boat. The sun-starved English couple and I immediately sought out the sunny section. One of the guides, whose name was Butati, introduced himself, the other guide, Matius, and the captain of the dhow, whose name I was unable to catch. Butati and Matius then produced from belowdecks a lunch of finger-food for us. They also provided drinks. I felt up to having a beer.[2] I was not too worried about getting sick in a boat.

While we were eating, Butati, who reminded me more than a little of Cleavon Little, regaled us with fun facts about Lake Tanganyika. It was 1,473 meters deep, second only to Lake Baikal in Siberia. It was also second to Lake Baikal in total volume, although its surface area was a little greater.[3] It snatched the gold medal in at least one category, length. Its north-south length was 420 miles, which was slightly more than the width of my home state of Kansas. Butati also claimed that it held 17 percent of the world's fresh water.[4]

Two main rivers and numerous small streams flowed into the lake. It was drained by one major river, the Lukuga, which fed the Congo River system, so that the water ultimately ended up in the Atlantic Ocean.[5]

The National Park owned the rights to the water within one mile of the coast, which was 60 kilometers long. Commercial fishing was prohibited in this area. Guests were allowed to fish on a catch-and-release basis. The lake was home to at least 250 different cichlids, the type of fish that was very popular in home aquariums. Ninety-eight of the cichlid species were endemic to the lake. Eighty percent of the non-cichlid species were endemic.

The most popular commercial fish was the yellow-belly, which locally was called "water chicken."

Two snakes, the water cobra and the Tanganyika water snake, could occasionally be found in the lake. Lake Tanganyika also served as part-time home to two species of otter, both Nile and slender-snouted crocodiles, and hippos.

Butati also talked about the villages that were visible to the left before we reached the National Park. The people there were engaged primarily in fishing for sardines and in agriculture. We later learned that he came from one of those villages.

We saw a palm-nut vulture flying almost parallel to the boat. I managed to get a shot of it, but I was unable to focus in on it.[6]

We also saw spotted red colobus monkeys on the shore. My old eyes could not detect them at all without using the camera's zoom, but I think that the camera managed to capture an image of one.

We passed the Flycatcher Camp, which appeared to be closed. Shortly after that a startling black and white bird flew up onto the rail. Butati told us that it was an African pied wagtail that actually had built a nest in the boat. We saw this one and its mate repeatedly throughout the visit.

The first view of the Nomad Camp was enough to knock anyone's socks off. It truly resembled a paradise in the wilderness, which is what it really was. When we landed, we were greeted by Kate, who was originally from southeast England. She apologized for the absence of her husband, Cam, who was suffering from sunburn as a result of playing cricket without benefit of sunscreen. Make no mistake; the equatorial sun was brutal twelve months a year.

Kate gave us a short orientation talk concerning the camp and the daily schedule. We learned that the chimpanzees that we would be allowed to observe formed a group of sixty-four adults and children. Other groups of chimps lived in the Mahale Mountains, but this group had been studied by various Japanese scientists for thirty years. The researchers referred to the ones that they studied as Group M. By 2015 these chimps were therefore quite comfortable in the daily company of humans.

At first light the team of trackers ventured into the woods and mountains to look for the chimps, which usually slept in a different set of nests in the trees every night. When the trackers located the chimps of Group M, they radioed back to the camp. The dhow then took the tourists as close as possible. The rest of the journey was a trek through the forest. It might be easy and quick, but it might be time-consuming and arduous.

Lunch at Greystoke Lodge was usually served at 1:30 or as close to that as possible. Everyone could assemble at the main banda for "tea" at 4.[7] Hikes and boat trips — for swimming, fishing, and wildlife viewing — were available after tea.

In addition, Kate insisted that it was completely safe for guests to swim in the water adjacent to the beach. Kayaks were available for the more adventurous (that is, younger) tourists.

At some point the star of the show, Big Bird, a great white pelican that had attached himself to the camp a year or two earlier, when he was a very young and helpless orphan. He had subsequently become an international star because of a YouTube video that went viral. You can view it here

At 7:00 everyone assembled up at the bar to watch the sunset and discuss the day's activities. When supper was announced, each tent was supplied with a powerful flashlight. We all paraded to the feast at the main building. The campfire in Mahale was held after supper was concluded.

There would be no chimp-viewing on the first day of our visit and none on the last day. So, we would have three opportunities to interact with the chimps. We learned that in one respect this camp was dramatically different from the previous camps. The entire group always arrived together and left together. The other camps allowed the tourists to stay as long as they wanted.

Sue and I had no interest in hiking or boating on that first afternoon. We were old, and old people prefer to nap. Some of the others may have gone out. I did not make any notes about that.

At the gathering in the bar in the evening Matius, who, we learned had recently been promoted from tracker to guide, presented a list of rules about interacting with the chimps. It was quite a long list.

1. Each human was required to wear a surgical mask whenever the chimps were near. A few chimps had apparently contracted fatal cases of pneumonia from visitors a few years back.

2. Humans must not get within ten meters of the chimps. However, the chimps sometimes violated the rule. If a chimp approached, stay still and let it pass.

4. No more than six tourists at a time may view the same group. We would always have two groups. It was possible to run into other groups as well. Patience might be required.

5. No flash photography.

6. No food or drink could be given to the chimps.

7. No food or drink could be consumed within 250 meters of the chimps. If it was necessary to do so, the guide should be contacted to escort the tourist away from the chimps and then back to the group.

8. Relieving of oneself was likewise prohibited within 250 meters of the chimps. If it was necessary to do so, the guide should be contacted to escort the tourist away from the chimps and then back to the group.

9. No clothing with images of gorillas or leopards or leopard spots was allowed.

There may have been another rule or two that I missed.

Pork filets comprised the entrée for supper. Everything was delicious. Kate told us to come to breakfast ready to go chimping the next morning. We might be able leave right after breakfast. We might have to sit around throughout the morning or even into the afternoon until the trackers located the chimpanzee troop. The chimps called the shots.

She also assured us that escorts were not needed in camp because it was safe. Well, …

[1] Greystoke Lodge was the official name of the place, but everyone calls it "Nomad Camp." Nomad was the name of the company that runs both Chada Camp and this one.

[2] Two of the most popular beers in Tanzania, Kilimanjaro and Safari, are produced and distributed by subsidiaries of SAB Miller.

[3] The combined surface area of the two deep lakes was less than the surface area of Lake Superior, which was not nearly as deep.