I rolled out of the sack a few minutes after five, shaved, took a shower, and then set to work on my journal. I went back to sleep at about 6:50, but I was awake again in plenty of time for breakfast. I must have been a little late getting down. The breakfast room seemed awfully crowded this morning. I did not see any hot water for tea. They seemed to have run out of coffee, too. I sat with Dorothy, Ruth Abad, and the Mazurs. Sue never made it down to breakfast.

There was talk of a rebellion. Everyone wanted to stay at the Castello for at least one more day. Sue told me that she and Ed Mazur were the instigators of the revolt. I opined that most people were a little sad that the tour was more than half over. There was no doubt that everyone was thoroughly enamored of the Castello. Nevertheless, everyone showed up on time for the bus. In fact, Sue and I were the last ones to board. I remembered that we had been the last to board when leaving the agriturismo in 2003 as well, and we had been publicly remonstrated for failing to wipe our feet on the bus driver’s mats.

We had a somewhat long bus ride from the Castello to another agriturismo named Il Poggio. On the way we stopped for a restroom break near a Holiday Inn of all things. After the break Nina handed out delicious soft Tuscan cookies known as Ricciarelli. This was really not a bad way to live.

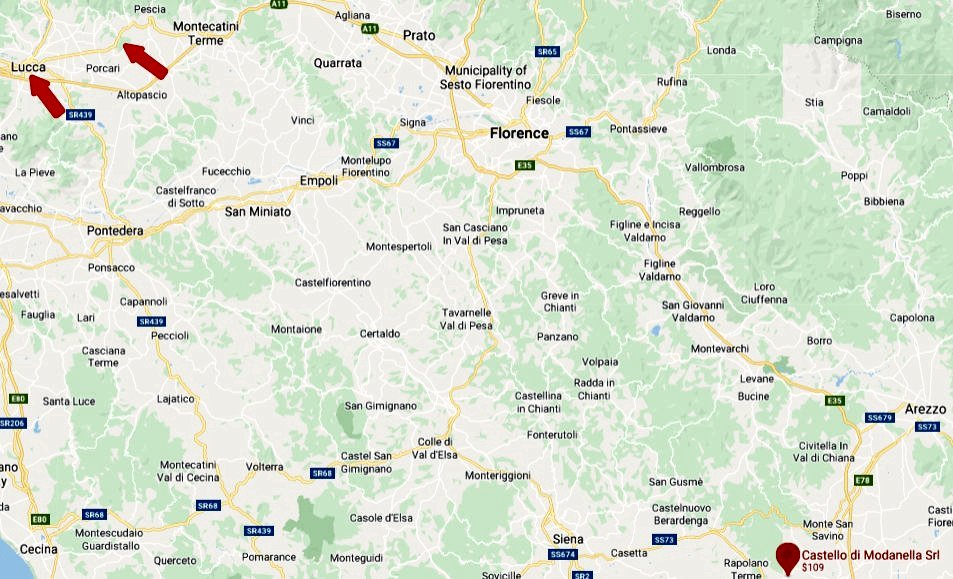

Il Poggio was near the village of Montecarlo, which was between Florence and Lucca. Montecarlo was named after Charles, a French prince or something who apparently was hired by the lucchesi to defend them against the Florentines. We learned that Charles' forces won the battle, so they named the small nearby mountain after him. The village, in turn, was named after the mountain.

Our guide in the tour of the estate was a clever little blonde lady named Elena (accent on first syllable). She had an excellent command of English, and she had obviously put in considerable time and effort developing her patter. She made no secret of the fact that she was from Lucca and that, like all lucchesi, she thought very little of the people from Pisa. The way the lucchesi express it is: “Better a dead man in the house than a pisano at the door.”

We walked through the vineyards with Elena and the large black dog Lazarone. At one point we passed a much smaller group of slow-moving French people who were being led on a tour of the estate a different guide. When we reached a spot between an olive grove and a wine grove, Elena explained about both crops.

She said that the poggio, which the dictionary defined as “hill, hillock,” referred to the fact that the olive and grape groves were raised a few inches above the level of the path. She told us that grapes are mostly roots; 80 percent of the plant was below ground. She also said that a plant can live forty to fifty years. The primary grape that they grow is Sangiovese, but they also grow Trebiano and several other kinds. The grapes are picked by hand. She claimed at first that they also pressed the wine with their feet – “red wine dirty feet; white wine clean feet” – but she later admitted that they use a machine for pressing. The skins and seeds are used to make grappa.

They grow both black olives (which are blue) and green olives (which are brown). Elena said that Tuscany was the northernmost location in Italy in which olives can be successfully grown. Further north it is too cold in the winter. They pick a lot of the olives at Il Poggio, but they also use nets and shake the trees. She said that her grandfather insisted that it is much better to use nets made of jute than of plastic, an opinion with which she concurred. She also said that olive oil will last three years if kept out of the light at room temperature. However, a bottle of olive oil in Italy only lasts a family one week because they use it on everything.

They also sell balsamic vinegar at Il Poggio. Elena said that it was so mild that they even use it on strawberries. I'll pass.

Elena and some other staff members of Il Poggio served us a fantastic lunch in a large room with a very high ceiling. Elena had us taste five bottles of wine – a dry white, a sweeter white, a mild red, a more robust red, and a “holy smoke” red wine aged in oak barrels from Canada. The wines sold here contain no sulfates (sulfides?), so they cannot be shipped to the United States.

Somehow the subject of note-taking came up. Elena wanted to know who was taking notes. Everyone pointed at me. She called me “schoolboy.” For some reason everyone seemed to think that this was hilarious.

Elena told us the percentage breakdowns of each of the wines served at dinner. I noticed that there was always one primary wine and several secondary wines. In every case the percentage of each secondary wine was the same. That is, no secondary had a higher concentration than any other secondary wine. I asked Elena why this was. She said that I should ask the owner, who made all of the decisions about making the wine. We did not, however, get to meet the owner, although we got a glimpse of his Mercedes Benz.

The meal started with a very tasty pasta. Then came a bruschetta of oil and garlic. Next were plates of salami and prosciutto with fennel and pecorino cheese. I made a sandwich using the salami and the fresh bread that they had placed on the table. They even brought seconds on wine – every thing except the “holy smoke.” The dessert was Tuscan almond cookies with vin santo. We even got a shot of grappa at the end. That was nine bottles of wine plus vin santo plus grappa for a lunch for a table of 12 people.

Elena was a very good salesperson. Almost everybody bought wine, olive oil, or both.

After lunch Mario drove us to Lucca. On the way Nina announced that after our orientation walk we would be renting bicycles to ride around the city on the top of the walls. Immediately someone announced that we should have a palio. This planted the seed of an idea in my fertile, or at least heavily fertilized, imagination.

The bus could only go as far as Porta Santa Maria. We walked from there to our hotel, the Albergo La Luna. Sue and I were in room 240, which was in the main building. It seemed strange to ask in Italian for the room key when the woman behind the desk was clearly from India. She complimented me on my pronunciation of duecentoquaranta: “Perfetto.”

Our room was on the second (i.e., third – they didn’t count the ground floor in Italy) floor. There was no elevator, so we had to carry our luggage to the room, which I considered truly amazing. The ceiling must have been fifteen to eighteen feet high. The room was rectangular, but the ceiling was square. It extended out over the bathroom and the hallway. The ceiling in the bathroom was only about eight feet. The ceiling in the room was painted with a blue pattern as one might expect in a ceiling of a Renaissance drawing room to be painted. There seemed to be a hole right in the middle for a chandelier. The windows were at least six feet tall; they had wooden shutters; and on the inside they were concealed by huge draperies. The most startling feature of the room was a pair of frescoes. The one over the bathroom was difficult to see from anywhere in the room. Some of the plaster had fallen off of both frescoes.

Sue decided not to participate in the orientation walk.

As usual we began our sojourn with an orientation walk through the city. This one was conducted by another woman named Nina, who was a native of the Flanders area of Belgium. She and her husband, Jamie, who was employed as a guide for Rick Steves, live in Lucca.

Lucca may be the only old city in Italy that has walls that were still completely intact. The Romans had originally built a small city of square walls. The still standing medieval wall encompasses at least twice as much as the old Roman city. The walls were about twenty yards thick, and there were a dozen or so bulwarks that jutted out much farther. The walls were designed to be thick enough to absorb any kind of cannon fire. Moreover, one hundred thirty cannons were mounted on the walls. Nina said that in those days the lucchesi had spent one-third of their income on self defense. No one ever attacked the city. In this area that was certainly amazing. Wars among the cities, the emperor, the pope, and foreign invaders were commonplace for centuries.

Nina said that Lucca became prosperous because of the silk trade. This was a little hard to fathom, since the town was 20 miles from the sea. They tried to get Pisa to allow them to use its port, but the Pisani would not let them. This refusal was evidently the source of the long-standing enmity between the two town. The lucchesi were force to travel to Genoa to launch ships.

Our hotel was on one of the main streets of Lucca, Via Fillungo. The group walked up the street a ways before stopping at the church of San Michele. This church was an important stop on the pilgrim’s tour in the middle ages. The bishops evidently felt the need to perform miracles in order to get the pilgrims to stay longer. One of the miracles that could be produced on demand was to get the wings on the statue of Saint Michael the Archangel to flap. Needless to say, the wings were on hinges, and the flapping was done mechanically.

Nina took us by the old Roman amphitheater, which was right on Via Fillungo. The shape has been preserved, but it is now a large round piazza with shops on all sides.

There are many places in which you can walk under or through the town walls. We explored a few of these places.

The best part of the tour from my perspective was Nina’s remarks about what it was like to be a foreigner in Lucca. She said that the public schools were very rigorous. At first she had enrolled her kids in a private school, but she soon discovered that, despite what the people at the private school had told her, the public schools were indeed open to foreigners and were just as good as the private ones. The only problem, from her perspective, was that the schools tended to emphasize memorization and rote learning over critical thinking and imagination. She said that at first she was very worried about the fact that they let the kids go out for lunch on their own once a week, but now she doesn’t worry about them at all.

Nina said that she and Jamie lived outside the walls of Lucca. Their neighbors all seemed to own lots of precious antiques and other such treasures. They generally kept their shutters and curtains closed to preserve them from damage. Nina and Jamie kept theirs open to allow in more lights. The neighbors thought that they were pazzo.

Nina’s biggest complaint about living in Italy was that it was very difficult to deal with the government’s bureaucracy. She said that she spent months getting the right stamps and forms to establish residency. Then she found out that she had been given the wrong forms and the wrong stamps. She asked for help from her neighbors. They shrugged and said, “Fumo negli occhi!” They also said that Nina and Jamie should never pay taxes until they see them paying them.

The tour ended at the bicycle rental place named Cicli Bizzarri. It was located in the vicinity of Porta Santa Maria. Almost everyone, including the two Ninas, took a bike. I decided to go in a clockwise direction around the wall because I was pretty sure that I could recognize the exit more easily from that direction. Almost everyone else seemed to go the other direction. The ideal weather made the cycling a quite pleasant experience. Most of the path was shaded by trees; the originals were planted by Napoleon’s sister in the early part of the 19th century. The bike path is almost perfectly flat. The only people who had a lot of trouble were the Boggetts. Barbara fell off her bike twice. The second time she almost crashed into someone. I learned later that Tom and Patti had stopped to help Barbara.

I did two laps, stopping a few times to take photos. On the last of these occasions Ruth Abad and Dorothy picked the same place as a photo op. I volunteered to take a photo of them together by the wall. This repaid them for the nice photo one of them took of Sue and me at the fish restaurant in Chioggia.

I returned the bike shortly after the break for photos. I was surprised to discover no employees present at Cicli Bizzarri to check in the bikes. Evidently they trusted us. I walked back to La Luna. Sue and I planned on consuming the leftovers and other things that she had accumulated for supper. Sue went down to the desk and cajoled them into letting us borrow some plates, silverware, and napkins. We had some cherry tomatoes, Sue made each of us a sandwich, and we had a few slices of cinghiale sausage. The food was pretty good, but we could have used some chips and something more interesting to drink than water. Let the record show that we proved that it was indeed possible to dine on the Italian peninsula without consuming any alcohol.

We considered attending the concert that Nina had told us about on the bus, but by the time that we determined where and when it was, the concert had already begun, or at least the scheduled starting time had passed. Who knows when it actually commenced? We decided to try to attend the one on the following evening. The one that we missed was the weekly performance of music composed by Puccini, who was born and raised in Lucca. The one scheduled for the next evening was a concert of Mozart’s music. Both were being held in a church that was in easy walking distance.

After our little meal we had planned to go out for a gelato or a drink, but I got into bed, and within seconds I was dead to the world.