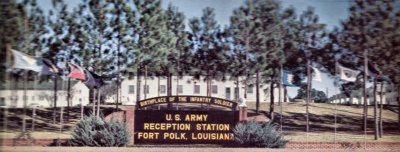

People I encountered at Fort Polk. Continue reading →

Fort Polk, which is named not for the U.S. president (which would be bad enough) but for a Confederate general, is near Leesville, LA.

Fort Polk, which is named not for the U.S. president (which would be bad enough) but for a Confederate general, is near Leesville, LA.

I never heard anyone on the base call the town anything other than Diseaseville. That was cleverer than the nickname for the base itself, Fort Puke.

It was pretty warm there, even in October and November. That suited me fine.

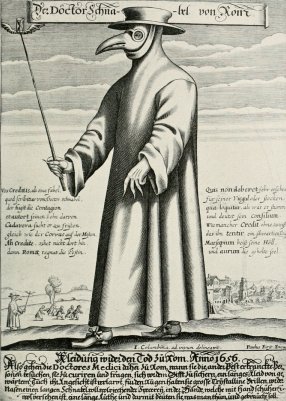

These are close to what we wore. Snazzy, eh?

Our first day was mostly devoted to waiting in line for haircuts and getting gear. You could tell the barber what you wanted: Class A (no hair), Class B (almost no hair), or Class C (a little hair). A few guys were stupid enough not to pick A. The sergeants made most of them go back in. Some ended up getting three or more haircuts. My military ID had a picture of me like this. I lost it in 1975 when I lost my billfold. Sue thought that I looked like a prison inmate.

Believe it or not, the measurements for my olive-drab (OD) trousers were 29-34. I wore nothing but fatigues for eight weeks. We were provided with an OD duffel bag in which to stow our gear. My name and Social Security Number were stenciled on mine. In the barracks we were each given a footlocker. Our army-issue stuff went in the footlocker in a precisely prescribed manner. Our civilian clothes and anything else we brought or acquired went in the duffel bag.

An important lesson we all quickly learned was this: Before you interact with anyone you must check his (there were no women to interact with in Basic training) sleeves and collar to determine his rank. Sergeants had at least three stripes. They were always addressed as “sergeant”. Officers had bars, oak leaf clusters (commonly called “salad”), eagles, or stars. They were always addressed as “sir”.

This is a true story. As we were waiting in line for something an officer asked one of the men a question. He did not like the answer and said “Give me twenty, boot.”

He was ordering the guy to do push-ups. The soldier addressed happened to be in great shape. He whipped off twenty and then said “Permission to recover, sir?”

The officer replied, “Sure, as soon as you give me my twenty. I didn’t hear anything.”

This time the guy called out “One”, “Two”, and so forth as he did his push-ups and then repeated the request to recover. The officer replied again, “Sure, as soon as you give me my twenty.”

My recollection is that the poor guy had done eighty or one hundred push-ups before he realized, after hints from the peanut gallery, that he needed to say “One, sir”, “Two, sir” and so on. Otherwise the officer would think that he must be responding to someone else’s order.

If you called a sergeant “sir”, he would undoubtedly say “I work for a living.” I don’t know what officers said if you called them “sergeant”. I avoided officers.

Our DS wore his hat much lower in front.

We met our drill sergeants. Ours was younger than I was. He wore his Smokey Bear hat tilted down at a very sharp angle. He gathered our platoon together at the very beginning and told all of us that we should never volunteer for anything. A few minutes later we had an assembly in which they asked for volunteers to give blood. Of course, absolutely no one in our platoon volunteered. The sergeant had to gather us again and tell us that giving blood was the one exception. Most guys then volunteered; I did not. My blood type is A+, the universal recipient. They never need it. Also, I have a rather severe phobia of needles. It was bad enough that we got unexplained inoculations every Wednesday. I was not about to volunteer for more skin punctures.

One guy in our company had completed his service in the Navy and reenlisted in the Army. He had to start as a private, but after training he was guaranteed the equivalent of his Navy rank. He ran a loan-sharking business for the other trainees. He would loan money until pay day. What were his rates? He kept it simple. “I give you one. You give me two on pay day. I give you five; you give me ten. How much do you need?” He had no shortage of customers.

One guy in our company had completed his service in the Navy and reenlisted in the Army. He had to start as a private, but after training he was guaranteed the equivalent of his Navy rank. He ran a loan-sharking business for the other trainees. He would loan money until pay day. What were his rates? He kept it simple. “I give you one. You give me two on pay day. I give you five; you give me ten. How much do you need?” He had no shortage of customers.

There were more enlistees than draftees in our company. The enlistees were required to serve three years of active duty; the draftees’ requirement was only two years. However, the enlistees were allowed to choose either their first duty assignment (at least 12 months) or their MOS (military occupational specialty). Neither of these guaranteed that they would not go to Vietnam. Many of the enlistees were surprised to learn this when they got to Fort Polk. They had been bamboozled by a recruiting sergeant.

The recruiting sergeants in those days had high quotas for certain MOS’s. One, of course, was infantry, but it was difficult even for them to portray slogging through rice paddies under enemy fire as romantic, exotic, or practical. On the other hand quite a few guys signed up for another MOS: “helicopter repairman”. They probably envisioned themselves in a bulletproof hangar doing interesting work and developing a marketable skill. Unfortunately, these guys learned that their job had a co-equal assignment as tail-gunner on helicopters, and their survival rate was not high.

One guy, whose last name and home town were both Houston, was a very unusual case. He was a very dim bulb. He had red hair and wore glasses that looked like the bottoms of coke bottles. He seemed more like a cartoon character than a human.

Houston’s life ambition was to be a quartermaster in the Army. Army quartermasters are in charge of supplies. They distribute field jackets, blankets, etc. He had twice tried to enlist, but he had been rejected because of his poor vision. Jack Vance solved this problem in 1941 by memorizing the eye chart. I don’t think that Houston had the mental acuity to do that, but he somehow got in on the third attempt. A lazy or overly gung-ho person probably looked the other way at his physical.

At Fort Polk Houston was crestfallen to discover that his enlistment contract did NOT guarantee that he would become a near-sighted quartermaster. He learned at the end of training that he was actually assigned to infantry. I wonder what happened to him.

We spent one day learning about grenades. They have two safeties

We spent one day learning about grenades. They have two safeties—the handle and the pin. You first squeeze the handle, then pull out the pin, then throw it and duck behind something solid. A few second later the grenade is supposed to explode. You never check it. Ten or fifteen minutes would be reasonable for this lesson. We spent half a day.

Before we were rewarded with the thrill of throwing a live grenade, we had to demonstrate that we understood the technique by throwing a dummy. I was standing in line when Houston’s turn came. The sergeant handed him the grenade. Houston looked at it quizzically, squeezed the handle, pulled the pin, dropped it and then kicked it as he tried to pick it up. Even the Army would not let him throw a live one. Of course, the pencil-pusher who assigned him to infantry did not know about this episode.

One other person in our company was not allowed to throw a live grenade, my bunkmate, whose last name was Rosensomething. Everyone except me called him Rosey. I called him by his first name, Larry. He had a degree in music. Both of his parents were also musicians. He had NEVER played any sport. He had never even thrown a football, a baseball, or anything else. His best effort at throwing the dummy grenade might have gone ten yards. It was beyond pitiful.

Rosey had perfect musical pitch and a fine counter-tenor (higher than Pavarotti or Juan Diego Flores) voice. When the sergeants discovered this, they would often have Rosey call the cadence or lead us in one of our semi-obscene marching songs as we marched from one training area to another. They found this very entertaining, and they loved to showcase his abilities when we passed within earshot of other training companies.

At the start of training Rosie was in horrible condition. I was usually next to him when we jogged every morning. In our first run he was winded within the first minute or two. The sergeants made it quite clear that it was everyone’s responsibility to make sure that everyone kept up. I often had to help Rosey stay on his feet, but I did not mind at all.

On one of the final days he had to run a timed mile in combat boots. His time was twelve minutes plus, which is horrendous, but it was much faster than he could manage the first week.

There were three primary topics of conversation in our barracks:

1) How tough I am;

2) How fast my car is;

3) How beautiful my girlfriend is.

Lots of guys carried around pictures of #2 and #3. I had nothing to contribute to these conversations beyond “Nice.”

After a few weeks of Basic, everyone knew precisely where everyone else stood with regards to #1. At the top of the list was a rather small black guy from Chicago who was a Golden Gloves boxer. He was in another platoon. The most bizarre experience of the entire eight weeks was when I walked into the barracks on a day that we had off. Everyone was talking about how this guy from Chicago had punched me out. A few people were outraged because they knew that I would never start a quarrel. It turned out that he had cold-cocked a guy from another platoon. The victim wore glasses and was about my size (but heavier; everyone was heavier).

The guy in the next bunk (no clue as to his name but I can visualize him: a typical kid of 18 or 19 from a rural town) made everyone look at pictures of his girlfriend standing by his Corvette. Before he left she had sworn her undying love. He wrote to her every day. She responded. However, she stopped writing about the fifth week. Somehow he found out a while later that she was seeing another guy and even letting him drive the ‘vette. This guy wanted to go AWOL, but a few of us talked him out of it.

I had a lot of respect for one guy from Mississippi in our platoon. He was married and had a kid. He enlisted because he could not find a job in his home town. When we got paid (something like $125 per month), he immediately endorsed his check and mailed it to his wife. You could live on the base without spending any money, but a “roach coach” came to our company every day, and it was very tempting to buy a candy bar or a bag of chips. He never gave in.

The intellectual level of our company was low. On a day that we had off I went around to all four barracks to ask if anyone knew how to play bridge (which in the sixties and seventies was played by college students everywhere). There were at least three hundred people in the company, but no one admitted to knowing anything about bridge.

My only real friend, other than Rosey, was another guy from Mississippi named Todd Pyles. He seemed like a pretty intelligent guy, but that did not stop people from calling him Gomer. He had attended Ole Miss for a couple of years, but he dropped out to join the army. His attitude could be summed up by his favorite aphorism, “They can kill you, but they can’t eat you.”

My only real friend, other than Rosey, was another guy from Mississippi named Todd Pyles. He seemed like a pretty intelligent guy, but that did not stop people from calling him Gomer. He had attended Ole Miss for a couple of years, but he dropped out to join the army. His attitude could be summed up by his favorite aphorism, “They can kill you, but they can’t eat you.”

At the end of week six or seven we were allowed to go to a place on the base where you could buy a beer. I doubt that I had had two beers in my life before this, but when Todd asked if I wanted to go, I agreed. We sat down, sipped our Miller High Lifes, and solved a few of the world’s problems. At one point I asked him why he had dropped out and enlisted when he could have stayed in school and avoided the draft. He said that he had problems. I asked him what kind of problems. He replied, “You know, heroin.” That shut me up.

A couple of guys went AWOL. One fellow from our platoon who went “over the hill” was a Latino named Victor. He was caught a few days later and brought back. Our drill sergeant gathered us together and told us that we should welcome Victor back and not quiz him about his attempted escape. He bugged out again a few days later, and we never saw him again.

I spent most of my spare time reading murder mysteries. I also bought a couple when, after a few weeks, we were allowed to go to the PX. I was known in the company as “the guy who reads.” I always carried a book with me. We had plenty of free time, but it usually came in intervals of only 15-20 minutes. These breaks were announced with “Light ’em up if you got ’em.” We had to sit on the ground. I would persuade someone to sit back-to-back with me while I read a few pages.

Having seen nearly every episode of “The Beverly Hillbillies”, I knew that the species existed, but I had never encountered one. There were quite a few hillbillies in our company and one in our squad of a dozen or so guys. He had a radio that was set to a local country station, and he turned it on every morning. I started every day in a bad mood for eight weeks.

There were two other subspecies that were new to me: Cajuns and Creoles. Both were very difficult to understand. We had one of the former in our platoon. I could not understand anything that he said. One of the drill sergeants had a Creole accent, which for him seemed to mean the elimination of most consonants. On one occasion one of his troops was missing. He went around screaming what sounded like “Weh ih eye ann owns?” with a heavy emphasis on the last syllable. He meant “Where is my man Jones?”

There were, of course, quite a few black guys. There had been none in my grade school and only one in my high school. Of course, there were some at Michigan, but fewer than you might think. The black guys in Basic did not seem much different from the other guys, but they all called one another “Holmes” or maybe it was “Homes”. One thing that they were adamant about was their refusal to eat pussy, not that I asked about it.

I never witnessed any overt discrimination, but who knows went on when I was not around?

The First Sergeant in any company is called “Top.” I had a run-in with ours. We were strongly encouraged to purchase savings bonds. If everyone did, they would get to post a banner boasting 100% compliance at HQ. Myself and a few others were not persuaded by this line of reasoning.

Top called our obstinate group aside while everyone else was eating lunch. He seated us in a small grandstand at a baseball field so that he could explain why saving money was good. When he finished his spiel, about half the guys, fearful of missing lunch, signed up and rushed to the mess hall.

I asked him what the interest rate on the bonds was. He said that he did not know. I told him that savings bonds at that time paid lower interest than savings accounts at banks. Elsewhere there were much better opportunities for saving than either of these. Both of these statements were true at the time.

I asked him what the interest rate on the bonds was. He said that he did not know. I told him that savings bonds at that time paid lower interest than savings accounts at banks. Elsewhere there were much better opportunities for saving than either of these. Both of these statements were true at the time.

He said that he did not believe that anyone offered a better deal than the United States government, a completely bogus argument. He also mentioned that the purchase could be deducted from the paycheck. This was a point, but if I was saving for a rainy day, I considered this period in which we were being paid so little to perform loathsome tasks to be a monsoon. I wanted access to every penny of my money.

Only a couple of us were left at the end. The lunch period was over, but Top got them to fix us something. I am not sure whether the others succumbed, but that banner never went up while I was there.

I had a similar experience with life insurance. The lady at the desk asked me if I knew what insurance was. I replied, “Yes, my father works for a life insurance company. I have worked at life insurance companies for three summers, the last two in actuarial departments. I have a degree in math, and I have passed the first two actuarial exams. I have no dependents, which makes me a poor candidate for insurance, and life insurance policies are horrible investments for someone like me.”

I suspect that she was supposed to press me to buy something, but she just let me go.

I kept a very low profile for all eight weeks, and I avoided any gathering that included officers or sergeants. In the eighth week one of the drill sergeants for another platoon in our company saw me in line at the mess hall. He challenged my right to be in line because he could not remember ever seeing me in eight weeks. The guys with me assured him that I was in their platoon. I was very proud of my anonymity.

We were inoculated every Wednesday. I dreaded these shots much more than anything else in Basic training. The last one was, by far, the worst. All the previous ones had been done by medics with guns. They took a split second. For the last one we got two shots, one in each arm, administered by doctors and nurses, and the needles were in our arms for at least fifteen seconds. The rumor was that these were black plague shots, but who knows? The sergeants and officers never told us, but they all knew what was coming.

We were inoculated every Wednesday. I dreaded these shots much more than anything else in Basic training. The last one was, by far, the worst. All the previous ones had been done by medics with guns. They took a split second. For the last one we got two shots, one in each arm, administered by doctors and nurses, and the needles were in our arms for at least fifteen seconds. The rumor was that these were black plague shots, but who knows? The sergeants and officers never told us, but they all knew what was coming. These shots were right after lunch, and we had no training that day. We went to the barracks and sat on our bunks. No one had any energy, and most of us slept. They woke us for supper, but half of the guys stayed in the barracks.

These shots were right after lunch, and we had no training that day. We went to the barracks and sat on our bunks. No one had any energy, and most of us slept. They woke us for supper, but half of the guys stayed in the barracks. I was not select for the language school. More than a decade later I learned from our company’s accountant that he had attended the school at Fort Lewis at about the time that I was talking with the captain. Only one language was being taught there, Vietnamese, and only one MOS was offered to the students, interrogator. Furthermore, most of these interrogations took place in helicopters. I was quite lucky that the Army in its infinite wisdom decided not to accept my offer to go to Ft. Lewis.

I was not select for the language school. More than a decade later I learned from our company’s accountant that he had attended the school at Fort Lewis at about the time that I was talking with the captain. Only one language was being taught there, Vietnamese, and only one MOS was offered to the students, interrogator. Furthermore, most of these interrogations took place in helicopters. I was quite lucky that the Army in its infinite wisdom decided not to accept my offer to go to Ft. Lewis.