The Air Force approach to policing. Continue reading →

The approach of the Air Force to policing was substantially different from what the MPs were accustomed to. The Army officers and sergeants interfered much less in the day-to-day operations of the police desk and the guys on patrol. In fact, in my experience they hardly wer involved at all. On the other hand, at four different levels the Air Force brass were much more hands-on. Sometimes they imposed discipline in important areas, but sometimes they were just disruptive.

- Our flight leader, Tech Sergeant Budick sometimes drove around in the patrol supervisor’s car. On midnight shifts he often came in to talk with Dick Madden about all kinds of subjects, mostly unrelated to work. For example, we learned what a great chess player his son was. “He can see several moves in advance!”

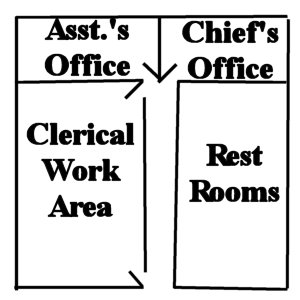

Sgt. Hungate, the top NCO in the Law Enforcement office (or whatever the Zoomers called it), often visited the police desk. He made certain that we all knew where the SOPs, checklists of tasks to be accomplished in the event of unusual but important circumstances, were, and he encouraged us to familiarize ourselves with them. The SOPs were contained in a big binder behind the police desk. He also asked a lot of questions.

Sgt. Hungate, the top NCO in the Law Enforcement office (or whatever the Zoomers called it), often visited the police desk. He made certain that we all knew where the SOPs, checklists of tasks to be accomplished in the event of unusual but important circumstances, were, and he encouraged us to familiarize ourselves with them. The SOPs were contained in a big binder behind the police desk. He also asked a lot of questions.- Sgt. Hungate’s boss, Capt. Creedon, was not around as often, but he was a stickler for details. I had one unpleasant run-in with him just before I departed.

- The base commander, a colonel whose name escapes me, liked to drive around in his big Jeep. He always had the onboard radio set to the police band. If something sounded untoward, he would demand to know the details. He even made surprise visits to the police headquarters.

Most MPs found this extra attention annoying, but Russ Eakle seemed to like the new environment. His new partner, whose last name was Fowler, somehow had wangled a transfer into the MP Company. My recollection is that he was formerly a medic, but I may be wrong. I never heard if Fowler called Eakle “Duke” or not.

The Duke appeared in Big Jake in 1970. Maybe this inspired Russ Eakle.

One day Russ really surprised me. He approached me in the barracks and told me that he wanted to purchase a motorcycle. Evidently he could not afford to pay cash for it. He said that a bank had told him that it would loan him the money, but he needed someone who was over 21 to co-sign the loan. I might have done this if (1) I did not already know that soon we both were going to be transferred to new posts; (2) I did not already know that I would ETS within a year, and Russ would not; and (3) Someone other than Russ Eakle was doing the asking. Russ was a little put out that I turned him down. Surely I was not the first person whom he asked, was I?

One night I was working the police desk. I am pretty sure that it was early in a midnight shift, but it might have been late in a swing shift. Sgt. Hungate walked up to the desk, which was about five feet high. Dick Madden, Dean Ahrendt, and I were sitting behind the desk. We were sitting on wheeled chairs on a platform raised a foot or so above where Sgt. Hungate was standing. So, we could only see his bald head. From there he could see all three of us, but if he took a step or two back we would be invisible to him.

“10-33, 10-33, 10-37.”

I was sitting nearest the microphone for the radio. Sgt. Hungate told me to issue the code that the station was under duress. At that time I knew the code well. I think that it was 10-37, but I might be wrong. I also knew the code for “all cars”, which I think was 10-33. So, I said, deliberately and loudly “10-33, 10-33, 10-37. I say again: 10-37.” Military personnel always say “say again” rather than “repeat”.

Sgt. Hungate critiqued my delivery. He had wanted me to issue the code in a nonchalant manner. I was aware of his intention, but he did not order me to announce it that way. I, of course, was worried that during such a dull period all the guys on patrol might be “cooping”, i.e., napping or goofing off. He would not be happy with them if no one responded.

What? No Snickers?

Hungate then told us to hide under our work table so that no one could see us without coming behind the police desk. He also ordered us not to make a sound. He also hid in a nearby office. Marshall Anderson, who was patrolling by himself1, broke the radio silence. “Kirtland Police, Police 9, 10-7. I need a candy bar.” “Kirtland Police” was the police desk. Marshall’s vehicle was “Police 9”. “10-7” was a request for a break.

Sgt. Hungate indicate that we should not respond. The desk ALWAYS responded. Guys on patrol were not allowed to take a break without approval from the desk. So, Marshall should have stayed in his truck in the parking lot and asked for a break again.

Instead, Marshall moseyed into the station, came into the area surrounding the police desk. and put his chin over the top of the desk. He could not see us. Then he called out “Hello!” a few times, shrugged, went into the break room, bought his candy bar, and strolled back to his truck in the parking lot.

Another couple of minutes passed. Russ Eakle, who was on patrol with SP5 Fowler, could be heard on the radio. “Kirtland Police, Police 13, say again the last transmission.” We stayed hidden and silent.

Shortly thereafter, Eakle and Fowler entered the station with their weapons drawn. My heart skipped a beat. This was the first (and only) time that I was around any MP with his hand-cannon removed the holster. E&F looked over the top and saw that no one was visible, but they did not come behind the desk. They heard a noise from upstairs, where the captain was working late. We could hear the two of them rapidly ascending the stairs. Hungate called out to them before they got very far, but he was facing two .45’s pointed at him while he explained the exercise.

I could think of many ways that this episode could have ended really badly. I was very relieved when those pistols went back in the holsters. I imagine that someone got chewed out over it, but I don’t remember ever hearing about it again.

That SOP binder was very useful on a couple of occasions. The first time was when Dean or Dick took a call from the manager at the commissary, who reported that someone had phoned him to warn that a bomb had been planted somewhere in the store. We dutifully executed the prescribed steps in order. The most important assignment was to cordon off the area around the commissary and evacuate everyone from the area. I don’t remember precisely how we managed to do this. We usually only had three cars on patrol. Maybe guys from the traffic area were shanghaied from the Day Room to help out. They were free most of the day.

That SOP binder was very useful on a couple of occasions. The first time was when Dean or Dick took a call from the manager at the commissary, who reported that someone had phoned him to warn that a bomb had been planted somewhere in the store. We dutifully executed the prescribed steps in order. The most important assignment was to cordon off the area around the commissary and evacuate everyone from the area. I don’t remember precisely how we managed to do this. We usually only had three cars on patrol. Maybe guys from the traffic area were shanghaied from the Day Room to help out. They were free most of the day.

Meanwhile we called the EOD (Explosive Ordnance Disposal) Team. It was their job to find the devices, if any, to remove them, and to dispose of them safely. Our primary responsibility was to keep everyone out of the danger area until EOD declared the area safe.

Meanwhile we called the EOD (Explosive Ordnance Disposal) Team. It was their job to find the devices, if any, to remove them, and to dispose of them safely. Our primary responsibility was to keep everyone out of the danger area until EOD declared the area safe.

The commissary was the size of a major supermarket. It took the EOD team more than an hour to search it thoroughly. They certainly did not want to hear a BOOM after they had declared the area clear. During that time traffic in one of the busiest parts of the base was seriously disrupted. Eventually, however, EOD told us that it was OK to let people back in, and we relayed the message to the guys on patrol.

A few minutes after the dust had settled, a red-faced Sgt. Hungate stormed up to the desk and demanded to know why we had failed to notify the base commander of this incident. Dick showed him the SOP for a bomb scare and pointed out that nowhere did it tell us to contact the base commander. Hungate examined the SOP for himself. We could see that his jaw was tightly clinched as he took the binder away and stomped up the stairs to his office. He returned it later with a revised list of steps for responding to a bomb scare.

As luck would have it, when, a few weeks later, a second threat was received, our flight was again on duty when it occurred. We followed all the revised procedures in our SOP binder. We sent the patrols to cordon off the BX, which was the size of a K-Mart. Once again the EOD team searched the store, found nothing, and issued the all-clear. This time nobody yelled at us.

As luck would have it, when, a few weeks later, a second threat was received, our flight was again on duty when it occurred. We followed all the revised procedures in our SOP binder. We sent the patrols to cordon off the BX, which was the size of a K-Mart. Once again the EOD team searched the store, found nothing, and issued the all-clear. This time nobody yelled at us.

Someone might have searched for the perpetrators of these threats, but it was not the patrols. This sort of thing was, as they say in the military, “above our pay-grade”. Either they caught whoever made the threat, or he/she/they was no longer entertained by the sight of us holding up traffic for several hours. There were no further threats while I was in Albuquerque.

The thought occurred to me that if I were planning a major crime on KAFB, I would have someone phone in a bomb threat first. We devoted 100 percent of available police resources to keeping people away from the threatened area. Nowhere in our SOPs did it say what we should do if a major crime was committed while the cops were all deployed to prevent angry motorists from entering thee threatened zone.

Air Force One was our imaginary guest.

Some time later, probably in November or December, we received word that an Inspector General was coming to the base for several days of inspections. Part of that effort would be an assessment of how security forces (us) would respond to unusual situations.

This time our flight was working the swing shift. The day shift had been required to deal with a make-believe landing of Air Force One at the Kirtland air strip. We figured that we were probably off-the-hook, but almost as soon as we sat down, the phone rang. I answered it. It was an unidentified guy claiming to have placed a bomb in the BX. I got as much information from him as I could before he hung up on me. We then executed our instructions as before. I think that we probably helped the base get good grades on the inspection. There was only one chance in sixteen that the same flight would handle all three situations, but it happened to us.

Two other memorable events occurred on our shift during the Air Force period. The first should have been routine. It was a very windy night. The alarms at the bank, the commissary, and the BX all sounded. Since no one was working at the time, they were presumably set off by detectors of sound or motion. It was unusual for all three alarms to sound simultaneously, but we had responded to a fairly large number of such incidents before the Air Force took charge. The MPs walked around the building to make sure that there were no intruders. Then we called someone to reset the alarms.

On this occasion we sent Sam Noce, a Zoomer with considerable experience, and his MP partner to check out the bank. Evidently his experience on the west side of the base did not include the wind setting off alarms. Maybe none of those buildings had sound/motion detectors. In any case, when they arrived at the bank, Sam drew his .38 and crept around the edge of the building with his pistol in the ready position. We had to tell him that although we always checked out the alarms, on windy nights the chance of false positives was close to 100 percent. So, the best strategy is to check thoroughly and, if anything is amiss, call for backup.

The other event occurred at the jail on the old Kirtland side. They had a prisoner, an AWOL I think. Somehow, the jailer, who was a good friend of both Dick and Dean, had made some mistake that allowed the guy to run away. After our shift was over we drove around the base looking for the fugitive, but we never spotted him. I don’t remember whether the jailer got in trouble or not.

The other event occurred at the jail on the old Kirtland side. They had a prisoner, an AWOL I think. Somehow, the jailer, who was a good friend of both Dick and Dean, had made some mistake that allowed the guy to run away. After our shift was over we drove around the base looking for the fugitive, but we never spotted him. I don’t remember whether the jailer got in trouble or not.

There were also a few incidents that did not relate to work. The new base commander organized a committee of enlisted (i.e., ranking below an NCO) personnel. Each unit was represented at their meetings by one person. Somehow, I was chosen to represent the MPs at these gatherings.

It was a meaningless role; the committee had no power. I don’t know what the meetings were supposed to accomplish; I don’t even remember anything that we discussed. The committee met during normal work hours. I was off-duty, and I was not about to don my costume for one of these meetings. So, I showed up in a golf shirt, flared pants, and my cowboy boots. By then I also owned a cowboy hat that I might have also worn. Everybody else was wearing their “Class A’s”. The base commander scowled at me, but he did not say anything.

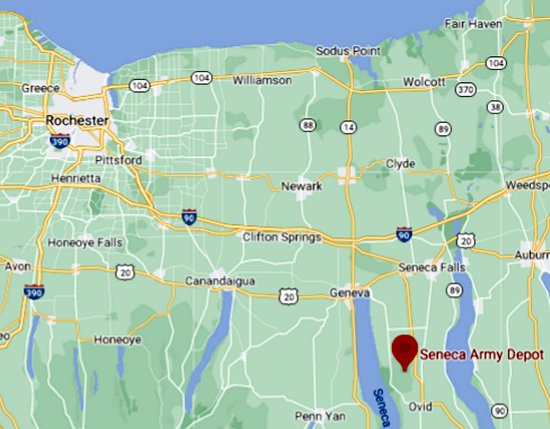

By December all of the MPs had been notified of their new duty assignments, and the draftees were told their new ETS dates. I was assigned to Seneca Army Depot, abbreviated SEAD, which was situated between two of the Finger Lakes in upstate New York. I was ordered to arrive on January 10. My new ETS date was April 10. So, I would be spending the rest of the winter in one of the snowiest parts of the country.

By December all of the MPs had been notified of their new duty assignments, and the draftees were told their new ETS dates. I was assigned to Seneca Army Depot, abbreviated SEAD, which was situated between two of the Finger Lakes in upstate New York. I was ordered to arrive on January 10. My new ETS date was April 10. So, I would be spending the rest of the winter in one of the snowiest parts of the country.

Almost everyone else was assigned to either Sierra Army Depot (SIAD) in California or Savanna Army Depot (SAAD) in Illinois. Most of my close friends went to Savanna. Despite the fact that I lived closer to SAAD than any of them and farther from SEAD than any of them, I was chosen for SEAD. I might have been the only guy from SBNM who was assigned to SEAD.

One day in December after I had finished working the day shift Lt. Anderson invited me into my office and delivered an encomium on the life of an Air Force officer. I was very short and was eager to return to civilian life. He then asked me if I was a college graduate. I admitted as much. When asked me what I majored I told him “Math”, and he quickly said, “Oh, forget about it. They would make you work with computers.”

The Air Force (or maybe just my flight) had an interesting policy for the holiday season. We fielded only a skeleton crew for both Christmas and New Years. The married guys, one of whom one was Dick Madden, all got Christmas off, whereas the unmarried guys, including Dean and me, all got New Years off. Therefore, Dean and I had to work the day shift on Christmas. I missed perhaps the greatest NFL game of all time, the two-overtime victory by Miami over the Chiefs, who were the defending Super Bowl champions. In KC this was known as the “Ed Podolak game”. He contributed a playoff-record 350 total yards: 85 rushing, 110 receiving, and an incredible 155 on returns, but it was not enough.2

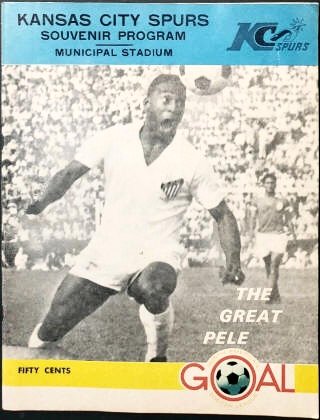

The Air Force (or maybe just my flight) had an interesting policy for the holiday season. We fielded only a skeleton crew for both Christmas and New Years. The married guys, one of whom one was Dick Madden, all got Christmas off, whereas the unmarried guys, including Dean and me, all got New Years off. Therefore, Dean and I had to work the day shift on Christmas. I missed perhaps the greatest NFL game of all time, the two-overtime victory by Miami over the Chiefs, who were the defending Super Bowl champions. In KC this was known as the “Ed Podolak game”. He contributed a playoff-record 350 total yards: 85 rushing, 110 receiving, and an incredible 155 on returns, but it was not enough.2

On New Years my flight was working mids. I celebrated my day off by sleeping. I don’t know what Dean did.

Yes, I know, but I only drove the danged thing ten yards!

One of my least pleasant memories of the ten months in Albuquerque occurred around this time. One of the guys had parked one of the trucks in the wrong place. I needed to move it to a different spot about ten yards away. There were a couple of other parked vehicles, but no one else was driving in the parking lot, which had space for at least twenty vehicles. Capt. Creedon saw me execute this fifteen-second maneuver and somehow noticed that I did not fasten the seatbelt before I did it.

He called me into his office and yelled at me for the better part of an hour. I suppose that he could tell from my body language that I did not take this situation seriously, but I don’t think he understood why. He probably thought that I was not lying or at least exaggerating when I claimed that I was always conscientious about wearing a seat belt when driving. In fact, that was absolutely the only time that I had EVER failed to wear a seat belt while driving. I had even persuaded both of my parents to buckle up.

I just knew that I only had to put up with this kind of Mickey Mouse stuff for only a few more months, and the knowledge revealed itself as a smug look on my face.

1. This certainly indicated that it was a midnight shift. Marshall was well known as a space cadet. We did not trust him to patrol by himself during business hours.

2. Thus ending the first of fifty years of frustration for fans of the KC Chiefs.