Working (or not) with the Zoomers. Continue reading

At some point in July 1971 the Air Force took over command of the entire complex. A gung-ho Air Force colonel whose name I have repressed and could not find on the Internet replaced General Nye as base commander. One person was now in charge of what was formerly three bases (SBNM, Kirtland AFB, and Manzano Base) that had separate commanders. At the time it seemed unusual to replace a two-star general, General Nye, the commanding officer at SBNM, a mere colonel. It came to mind that Jack D. Ripper, the commanding officer at Burpelson Air Base, was only a one-star general. To my knowledge our new CO did not obsess about fluoride. On the other hand, …

At some point in July 1971 the Air Force took over command of the entire complex. A gung-ho Air Force colonel whose name I have repressed and could not find on the Internet replaced General Nye as base commander. One person was now in charge of what was formerly three bases (SBNM, Kirtland AFB, and Manzano Base) that had separate commanders. At the time it seemed unusual to replace a two-star general, General Nye, the commanding officer at SBNM, a mere colonel. It came to mind that Jack D. Ripper, the commanding officer at Burpelson Air Base, was only a one-star general. To my knowledge our new CO did not obsess about fluoride. On the other hand, …

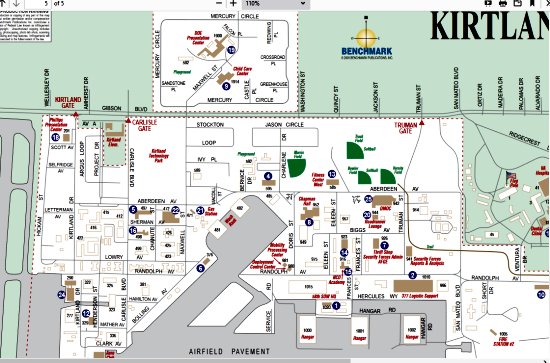

This is the west side of the base. On the west (left) is the Sunport. On the east is the old SBNM. I don’t remember where the jail was. I am not sure that the Mercury Circle area on the north side of Gibson Blvd. was then part of the base.

For reasons that will soon become apparent, I don’t remember too many of the details of the transition. In some ways it was a little weird. From a policing perspective SBNM was much more complicated than Kirtland AFB (KAFB). KAFB had a one-cell jail, and SBNM had none. In every other respect SBNM was larger and much more complicated to police. SBNM contained much more land, had far more permanent residents, and was home to New Mexico’s largest employer, Sandia Labs. The facilities such as the Commissary and BX on SBNM were much larger. I am not sure KAFB even had such stores.

The Law Enforcement Office in which I was working was almost immediately turned over to the Zoomers from KAFB. Capt. Huppmann was replaced by Capt. Creedon, and Sgt. Edison by Sgt. Hungate, who were both much more gung-ho than their counterparts. Another Air Force captain, whose name I don’t remember, was also above Creedon. He might have replaced Capt. Dean. I also remember a Black guy named Lt. Anderson. I don’t know what his precise function was.

I never met the Air Force guys, if any, who replaced Duffy and me. We were not asked to train anyone. We were both simply told not to come to the Law Enforcement office any more and to report to our platoons. Duffy may have been assigned an office job; the Army guys still handled personnel-related issues for MPCO. I am not sure that I even saw Duffy after we were booted out.

I never met the Air Force guys, if any, who replaced Duffy and me. We were not asked to train anyone. We were both simply told not to come to the Law Enforcement office any more and to report to our platoons. Duffy may have been assigned an office job; the Army guys still handled personnel-related issues for MPCO. I am not sure that I even saw Duffy after we were booted out.

As for me, on my first day after getting fired I went downstairs as usual to check the duty roster. Our old platoon was now considered a “flight” consisting of MPs and Air Force “security police”1. Tech Sergeant Budick was now in charge. Sgt. Glenn served as patrol supervisor (a demotion) for a while. I don’t remember if Sgt. Bailey continued to work on the police desk or not. Two Air Force guys, Dick Madden and Dean Ahrendt, worked the desk. I am pretty sure that within a few weeks both Sgt. Glenn and Sgt. Bailey were transferred to other units somewhere. In 2020 it surprises me that I have absolutely no recollection of when or where they (or almost anyone else) went. To me they were just two lifers who were no longer part of my existence.

The main thing that I noticed on our flight’s duty roster for that first day was that my name was missing. That meant that I had the day off. It was also missing on the next day and the day after that. Something was definitely amiss. I did not inquire as to who made the duty rosters after the merger, but no one was EVER given three days off in a row. Two days out of nine (we worked three sets of each shift and then had three days off) would be rare. So, I became convinced that my name was not on the official list2 of guys in my flight. For work purposes I had disappeared.

The main thing that I noticed on our flight’s duty roster for that first day was that my name was missing. That meant that I had the day off. It was also missing on the next day and the day after that. Something was definitely amiss. I did not inquire as to who made the duty rosters after the merger, but no one was EVER given three days off in a row. Two days out of nine (we worked three sets of each shift and then had three days off) would be rare. So, I became convinced that my name was not on the official list2 of guys in my flight. For work purposes I had disappeared.

I put together a plan to make the most of the situation. It involved making myself as invisible as possible. I trusted everyone in the platoon, except maybe Russ Eakle, not to rat me out. The strength of the spirit of omertà had already been well demonstrated by the fact that, despite all the investigations no one had been held responsible for trashing the hallway during the night of July 4-5. So, my plan was to avoid all lifers and Eakle entirely. I would also keep contact with the guys in the other platoons down to a minimum. The main element of my strategy was to spend as much time as possible on the UNM golf course. That meant that I had to keep in fairly close contact with Don Beeson and Terry Burnett, my playing partners and source of transportation. Finally, I never brought up my situation at all. If someone asked me about my status, I answered as briefly as possible. I NEVER gloated.

I realized that my failure to report the anomaly in the duty rosters might result in other guys missing out an opportunities to take a day or two off. However, the way that I looked at it, the Nixon government, as represented by the lifers, had stolen at least eighteen months of my life (plus all those years in the reserves) when I was in my prime. I was just getting a few days (OK, weeks) back. I feel certain that almost anyone else in my position would have done the same.

For a few weeks everything went according to plan. I checked that I was not on the duty roster early every morning. On most days I then played golf. If that was not possible, I made myself scarce. Whenever the platoon was working the day shift or the swing shift, I stayed away from the barracks. I spent time in the stores on the base or the movies. I sometimes just found a quiet place to read. At some point I heard that a guy whom I barely knew in another platoon (and who was less discreet than I) had also had been left off of duty rosters. A day or two later his absence was discovered, and he went back on patrol.

My unanticipated sabbatical lasted almost six weeks. This period is my biggest regret of all of my time in the Army. At the Thrift Shop on the base I had purchased an ancient Underwood portable typewriter. I could have spent that period writing up my recollections of the nine bizarre months that I already spent in the Army. I have long thought that I could have created a best-selling book from this experience.

My unanticipated sabbatical lasted almost six weeks. This period is my biggest regret of all of my time in the Army. At the Thrift Shop on the base I had purchased an ancient Underwood portable typewriter. I could have spent that period writing up my recollections of the nine bizarre months that I already spent in the Army. I have long thought that I could have created a best-selling book from this experience.

I don’t remember who discovered my situation or how. Perhaps because nobody expected a draftee to volunteer for anything, nobody “jumped in my shit”. One day my name just appeared on our fligh’s duty roster. So, I showed up. However, the routine of guardmount, patrolling, and gate duty only lasted a few days. Thereafter I was assigned to work on the police desk with Sgt. Dick Madden and Sgt. Dean Ahrendt. By the way, in the Air Force a sergeant is only an E-4. So, despite the fact that both of these guys had spent a lot more time in the military than I had, we were all at the same pay grade.

So, I did not actually cost my friends any days off. The only people affected were Dick and Dean, and when they learned that I was joining them, they were delighted that they would now be able to take an occasional day off. Neither of them gainsaid me for taking advantage of my situation. We actually became pretty close friends even though they must have wondered why they had volunteered to spend four years in the Air Force doing the same job as an Army guy whose commitment to active duty was now two and a half years shorter than theirs.

The job itself was pretty much the same as what I had been accustomed to from the time that I worked with Sgt. Bailey. We operated out of the same building as before, but we now called it Kirtland Police headquarters rather than the PMO. Our two primary responsibilities were dispatching patrols to deal with whatever events came up and using the same old manual typewriters to produce reports and logs. A few differences stood out:

- There was a little more to do. The Kirtland side had an active air strip and a jail. We sometimes had to send someone to relieve the jailer.

-

An SP5 named Fowler, formerly a medic or something, became a member of MPCO and patrolled with Russ Eakle.

- The base commander was MUCH more active, especially at night. He drove around in his big Jeep, and he always listened to (and occasionally talked on) the police band on the radio. He even occasionally popped into the police station uninvited.

- Sgt. Glenn had never visited us at the police desk; Sgt. Budick, on the other hand, liked to talk to Dick Madden, especially on midnight shifts.

- The Air Force guys carried .38 caliber revolvers.

- Two dozen or more very young, very inexperienced airmen showed up to replace us. Because they had not been trained or tested on the handguns, we could not use them for anything but gate duty. They also lacked security clearances.

- The Air Force used a different 10 series for coded radio communications. The MPs had to memorize it.

1. General Ripper called his defenders on Burpelson Air Force Base “air police”, but I never heard the Zoomers use that term.

2. In all likelihood the same list used for the duty roster was also used for the list of potential witnesses after the July 4 incident. Mine was the only name missing from either list. This did not occur to me until years later.