Studying and taking. Continue reading

The official title of my job at the Hartford was “actuarial student”. I had two responsibilities—helping with the actuarial work assigned by my bosses and studying for the actuarial exams sponsored by the Society of Actuaries (SOA). It is more complicated now, but in 1972-74 there were ten exams (called “parts”). To become a Fellow of the SOA one needed to all ten. Passing the first five granted one the title of Associate.

For actuaries advancement at insurance companies depended much more on success on the exams than on performance at the workplace. Becoming a Fellow was a big deal. At least one person at the Hartford immediately after passing the tenth exam got a vanity plate for his car with his initials and “FSA”. Some people hired tutors for difficult tests. It could easily be worth the expense; at the time surveys ranked actuaries as the highest-paid occupation in the United States. For decades the number of actuaries increased by over 6 percent per year, and in the seventies demand still exceeded supply.

The actuarial exams were held twice a year—in May and November. The first four were offered both times. Some of the other six were offered in May; the rest were scheduled for November.

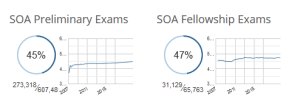

Everyone who has taken them agrees that the exams are very challenging. A few people have taken more than one at a time, but most thought that one was enough. Less than 50 percent of the people pass each test. Many people, myself included, dropped out along the way. The ones taking the higher level exams were by no means a random sample; they had shown the ability and determination to outdo some really smart people again and again.

The Hartford, as well as most other insurance companies, granted actuarial students time during work to study for exams. I think that we got thirty hours for each exam period. Most people took the hours in increments of an hour or two at a time. I always studied in the morning. I came in early and then used an hour and a half of study time. My recollection is that to maintain this privilege one needed to pass at least one exam per year.

The study room on the twenty-first floor was between the elevators and an exterior wall. It consisted of a conference table and, if memory serves, six or eight chairs. For the most part everyone took advantage of the time to study silently and diligently. Occasionally, of course, someone (usually Tom Corcoran) would doze off. We just let them sleep unless the snoring got too loud.

I remember two unusual occurrences. The first involved Pat Adams, an exceptional student who never made any noise in the study room. [This is a good story, but it would be better if I could somehow act it out.] One morning Pat clearly needed to sneeze. She inhaled sharply and then let the breath out. She inhaled sharply again and then emitted something much closer to “Pfft” than “Ahchoo” (or, in my case, a Category 5 blast of AHCHOOOOOO repeated up to eight times).

Upon hearing Pat’s timid sneeze I felt compelled to break the monastic silence of the study room in order to declare that hers was the most pitiful sneeze that I had ever witnessed.

The other occasion of note occurred when Mike Swiecicki and Damon Panels became embroiled in an argument over who was on third base in the ninth inning of a baseball game from a decade or so earlier. It was the kind of dispute that could be solved with Google in less than a minute, but, of course, that was not possible in the seventies. Mike and Damon went on and on, each adding details from his own recollection to try to persuade the other to cede the point. I don’t remember if either of them was ever proven right. It is important to not that no one reported them for breaking the vow of silence because everyone judged that the strictures of l’omertà applied.

UConn offered evening classes at its Hartford campus for the first four exams. I took two of these classes, and I seem to remember that the Hartford paid the tuition.

Over the years I took the first six exams. All the questions on the first five tests were multiple choice. The multiple choice questions were very carefully designed so that all of the answers seemed reasonable. To discourage guessing, a percentage of wrong answers was subtracted from the number of right answers.

Each exam was scored on a scale from 0 through 10. The minimum passing score was 6 on each test. Here is a description of my experience with each exam:

Part 1: The topic was “general mathematics”. Most of the questions involve algebra and/or calculus. I took the exam in my sophomore year at U-M. I did not study at all. My score was a 6. I thought that I had done much better than that. I probably guessed too much.

Sue Comparetto took this exam several times, but she did not pass. Of course, she also did not have the benefit of study time or free classes.

Part 2: The topics were probability and statistics. The first time that I took it was in November of 1969 right after I had taken classes at U-M in both subjects from Cecil Nesbitt. I was too busy with debate and other extracurricular activities to study. More details can be read here. I was not worried about passing, but I should have been. I only received a 4.

I took the test again in May of 1970 in Ann Arbor. Once again I did not study even for a minute, this time out of ennui and disillusionment with the world in general. I was especially shaky about statistics. As the tests were being distributed, I decided to skip all statistics questions except the ones that I was absolutely certain of. In actuality, I answered every probability question and no statistics questions at all. I assumed that I had flunked, but I somehow squeaked through with a 6.

Part 3: The topics were finite differences (about which I remember absolutely nothing) and compound interest. I took this exam in November of 1972 in Hartford. During the previous few months I had attended classes in these subjects at UConn/Hartford. The subject matter seemed rather simple, and I used all of my study time, but I still only managed a 6.

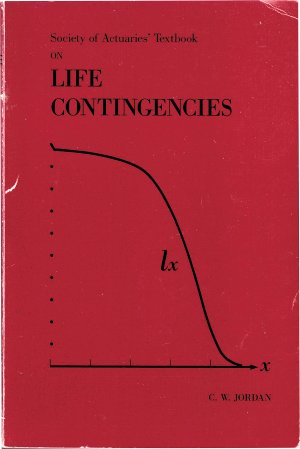

Part 4: The topics was life contingencies. I took the test in May of 1973. Many actuaries considered this the most difficult exam. Once again I attended the classes in Hartford. This time I supplemented my study time with some additional time, but the weather was starting to get very nice in late April and May. By then I also had something of a social life. I counted myself lucky to score a six.

Part 5: There were four exceptionally boring topics: 1) demography (the study of individuals moving in and out of groups over time); 2) principles underlying the construction of mortality and other tables; 3) elements of graduation of mortality tables and other series; 4) sources and characteristics of the principal mortality and disability tables. If the choice had been mine, I would never have considered studying any of these topics. I hated every second that I spent in all four areas.

I took this test in the fall of 1973, a very bad period for me. There were no classes. I studied as hard as I could at the Hartford, and I tried to make myself study at home. However, there were many distractions, and by then I had pretty much decided that I wanted to abandon the world of insurance and return to U-M if possible to coach debate. At the end of the exam, I was pretty certain that I had failed, and I was right. I got a 4.

Part 6: There were three topics: 1) actuarial aspects of life insurance accounting; 2) valuation of liabilities; 3) investment of life insurance funds. I took this test in the spring of 1974. By then I had already been offered the coaching job at U-M, and I accepted it. I planned to leave the Hartford forever in August.

I really wanted to pass this test. I knew that I would never use any of the knowledge that I was cramming into my skull, but I did not want people to think that I was quitting because I could not pass the exams. As it happened, however, my social life had improved by that point. That factor, my excitement about the adventure that awaited me in the fall, and the fact that the accounting aspect was insufferably boring made it difficult for me to keep my nose to the grindstone.

The first part of the exam was short answer/essay. I felt pretty good at the break about my performance. However, I did not feel at all good about the multiple choice questions in the afternoon. I was therefore not surprised when I received another 4.

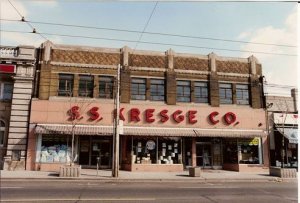

The investment part of this exam was ludicrous. The Society still used a horribly dated textbook that recommended that companies concentrate their investments in downtown real estate properties occupied by department stores like F.W. Woolworth and S.S. Kresge. A few typewritten pages were provided to students to replace these comical suggestions.

After I left the Hartford area, the thing that I missed the least was studying for and taking the tests. The math was not as difficult as what I encountered at Michigan, but at least half or the material was, for me, horribly boring.