She knows there’s no success like failure, and failure is no success at all.—Bob Dylan’s “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” Continue reading

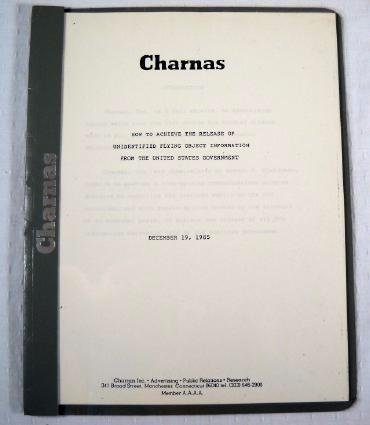

In the early years of the marketing of TSI’s GrandAd system for advertising agencies I distinctly remember being disappointed that the second installation (at Potter Hazlehurst) was even more difficult than the first. This tendency was definitely repeated with the system for retail advertising departments, AdDept (design described here). The second installation, which was began in the spring of 1990, was much more problematic than the first.

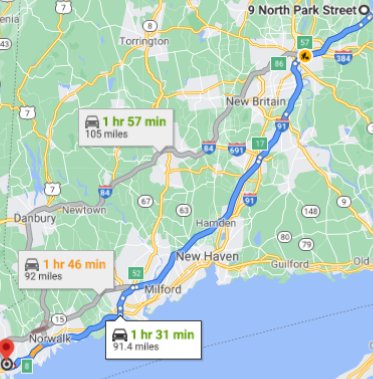

I had never heard of P.A. Bergner & Co. I now know that the chain’s original store was in Peoria, IL. After it acquired the Boston Store chain in 1985, the company moved its headquarters to the upper floors of the Boston Store in downtown Milwaukee. In 1989 the company also acquired the Carson Pirie Scott stores. The corporate management of all of these stores, including all aspects of advertising, was handled in Milwaukee.

I was not yet familiar enough with the nature and history of American department stores to understand the importance of the timing of that last acquisition. Bergner’s advertising department was presumably given a budget to acquire a computer system to enable it to handle the absorption of the Carson’s stores. The money probably had to be spent in 1990. Any portion that was not spent vanished. Little or nothing for future years was budgeted. I came to understand these things later. I wish that the situation had been spelled out to me.

Moreover, Sue and I continually tried to portray TSI as a strong stable organization that was especially good at big projects. That was true a few years later, but in 1990 the company consisted of:

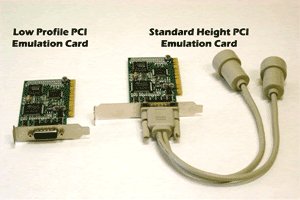

- Me,

- Sue Comparetto (who basically wrote checks, closed the books, and did presidential stuff),

- Sandy Sant’Angelo, who could do simple programming, of which there was still quite a lot,

- Kate Behart, who helped with marketing and served as day-to-day contact with some clients,

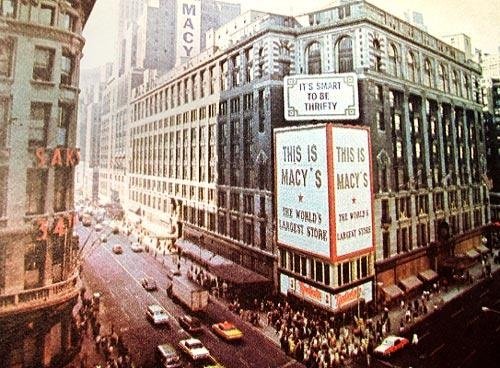

- Denise Bessette, who worked only part time, all of which was devoted to projects for Macy’s East,

- One or two administrative people.

The only way that the whole Bergner’s project could be implemented on time was for me to do almost all the programming work myself. The closest that I came to admitting this to Bergner’s was when I told them that Sue was terrible about time. Anything with a deadline had to come through me. Dan Stroman was quite taken aback when I said this. I was also pretty shocked when I had discovered this, but there was no sense in denying it.

Several IBM reps were involved in the sale of the AS/400 for the AdDept system to Bergner’s. The one whom I remember best was Sue Mueller. One of our last meetings took place shortly after the trip that Sue Comparetto and I took to England (described here). Sue brought to Milwaukee a copy of the magazine. When Sue Mueller saw my picture on the cover, she literally did not believe that it was a photo of me.

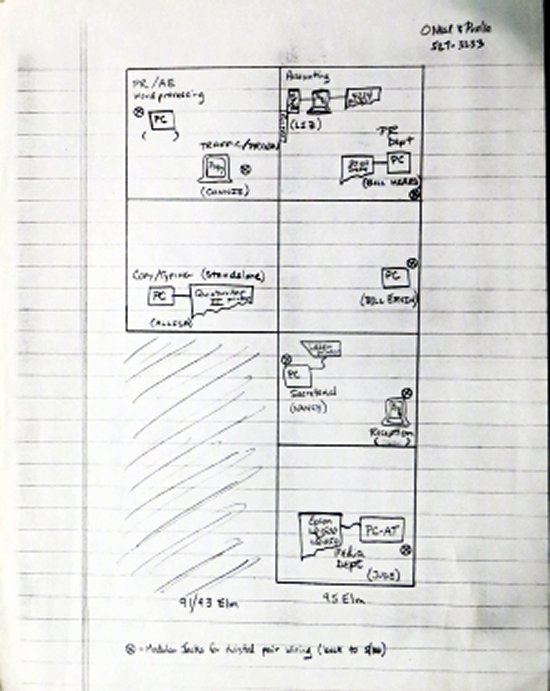

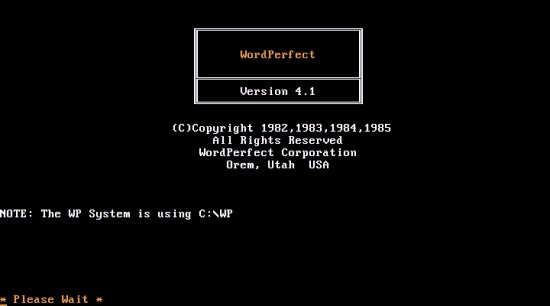

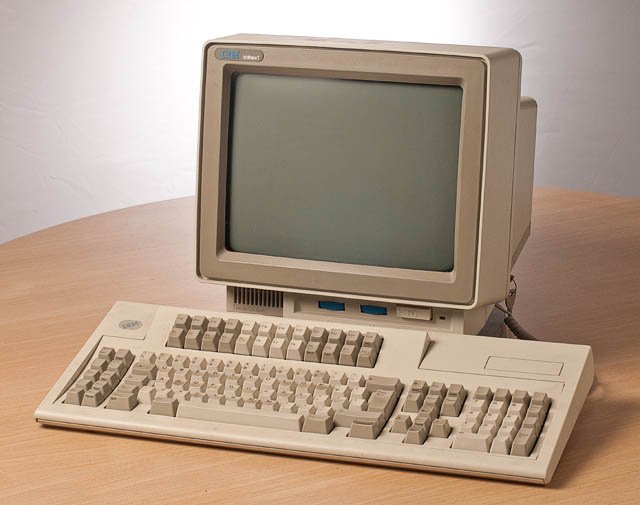

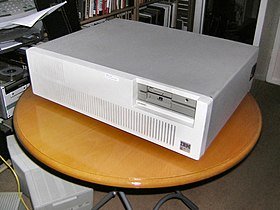

My recollection is that IBM sold Bergner’s a model B30 of the AS/400, the same machine that Macy’s was using. I think that it also had the faxing software and the modem that it required, and it definitely included OfficeVision/400, the word processing software.

Our primary contract person at Bergner’s during the negotiations was Dan Stroman1, who was either the advertising director or the production manager. He arranged for me to meet with the individual managers—production, ROP, direct mail, and business office. Either I did not do a very good job of collecting the requirements from them, or they did not do a good job of describing what they needed.

We tried to emphasize to Dan the importance of having one person designated as the liaison between TSI and the users. At first he wanted the liaison to be a person from the IT department. However, everyone agreed that the person whom the IT department assigned to the project, Kee-Huat Chua, would never have worked for many reasons. So, the job was given to Sheree Marlow Wicklund2, who at the time was the manager of the merchandise loan room.

I don’t think that in 1990 TSI yet owned the tools to produce detailed design documents. If we did, we certainly did not use them for that purpose in this installation. I merely described in the proposal what we planned to do.

The project was focused on quite a few things that required significant design changes.

- Bergner’s stores had four or five logos (the name on the store’s signs). So, a table for logos had to be created, and separate versions of each ad were needed for each version of an ad.

- On some pages of some direct mail catalogs and newspaper inserts the merchandise varied by market. That is, one “block” on a page might show items from one department in one market and different ones in others. Bergner’s called these “swing pages”. Providing a way to handle them meant, among other things, that the entire approach to measuring books needed to be rethought.

- Bergner’s wanted to use the system to “traffic” production jobs. We proposed to do this by defining lists of steps, which we called “production schedules” and “timetables”—date relationships to the release date (the date that the materials were delivered to the printer or the newspaper). This approach worked well for setting up the original schedule, but the traffic coordinators did not like to use it, and I never did figure out how we could make it more useful for them. Sheree was certainly of little help.

- Macy’s newspaper coordinators ordered their space reservations by phone. Joyce Nelson3, the newspaper manager at Bergner’s, sent a schedule to each paper once per week with all the ads, positioning requests, and other notes for every ad to be run in that paper over the next week. She wanted the system to fax them all. I was very happy to add this feature.

- Bergner’s employees wanted to be able to record comments in many places. These requests were often difficult to accommodate. I devised a trick to handle some of them. IBM’s office-vision software had the ability to run programs within documents and to display the output sent to an output queue within the document instead! The parameters for the program could even be included in the document. So, a form letter could be created for sending detailed information about an ad to a group of people. The text surrounding the report could be changed every time. I especially liked this approach because I was fairly certain that it could not be replicated on any other system.

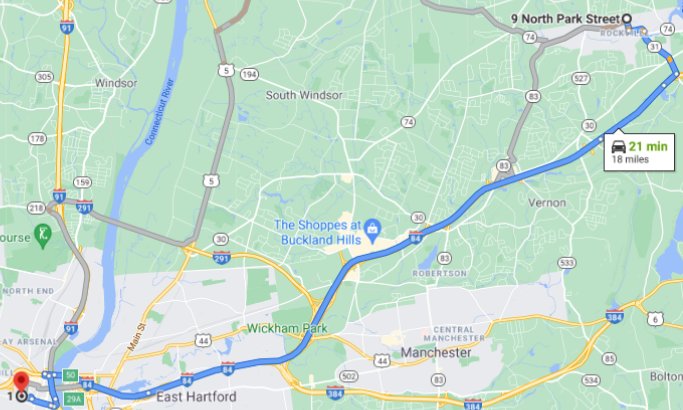

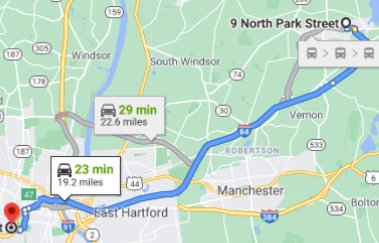

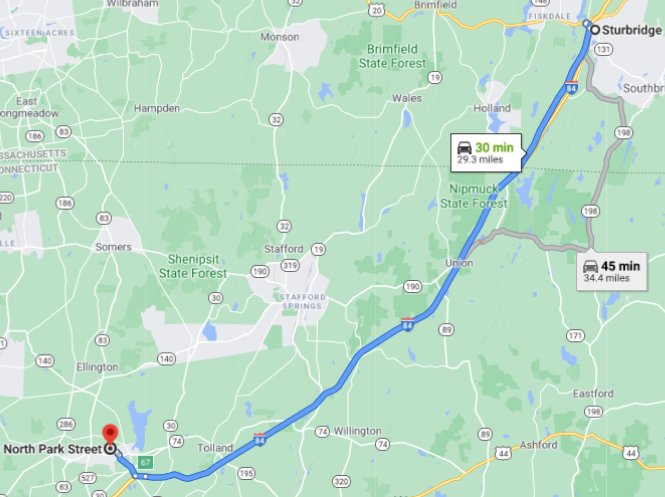

By the time that the software was delivered, TSI had a small AS/400 in its office, and we quickly established peer-to-peer communication with Bergner’s system. This allowed us to sign on to their system from TSI’s office and to send programs directly from our AS/400 to theirs over the phone lines. I worked all day on programs in TSI’s office and installed the ones that I deemed to be working early in the morning. This was feasible because our office was an hour ahead of theirs.

I communicated with Sheree via the AS/400’s messaging system, which supported both plain text and word processing documents. Kate communicated with Sheree by telephone. I expected Sheree to interact with the users and managers personally. Instead they had weekly meetings that all the managers attended. They appear to have been mostly gripe sessions. Sheree took notes and sent me a list of the issues reported. She did not send one document per area; all areas were included on one document.

I liked the idea that we received a written record of the issues, but my responses expressed my exasperation at some of them. Often users were still complaining about things that I was positive had been fixed. In other cases they had changed their minds about decisions that they had previously made and we had implemented. I responded to all of the issues that Sheree had sent in one document. I did not anticipate that Sheree would share all of my responses with all of the managers. I guess that I should have anticipated that possibility, but I had not worked at a large company for seventeen years, and the meetings at Macy’s were usually limited to one area at a time.

At any rate, I ended up on several shit lists because I responded negatively in print to some managers’ comments, and all of the other managers got to read. It never occurred to Sheree that if I had wanted everyone to read my answers, I could easily have sent the document with the responses to each of them.

Privately I was outraged that Sheree had violated what I considered to be a special relationship between the developer and the liaison. I expected her to be a strong advocate for the system when working with the users and an equally strong advocate for the users when speaking with us. She evidently considered herself more of a project manager whose responsibility was to organize and keep everyone informed. She did this. However, for such a complex system with such a compressed timeline, this was just not enough.

I talked with Dan about the situation, and I pleaded for a different liaison. He said that it was out of his hands. Ouch.

The installation at Bergner’s should have been a great success story. Some of the areas—notably the newspaper and loan room areas—were working very well in record time. The other areas proceeded much more slowly. I felt extremely frustrated by the incredibly inefficient process upon which Bergner’s insisted.

Nevertheless, by the time of my visit in December of 1990 the ill will had dissipated to the point that they invited me to the department’s Christmas party. I could hardly believe it. A live band was playing. There was a mosh pit! The young people who worked in the creative and production areas were going crazy. The old fogeys with whom I dealt were much more subdued.

That evening Joyce Nelson asked me to give her a demonstration of my technique of throwing playing cards. She produced a deck of bridge cards, which are not as easy to throw as poker cards. However, I was sure that I could spin one at least twenty yards. Unfortunately, the ceiling was too low. To get a card to go a long way, its flight must describe a loop. I could not possibly throw a card at high velocity without it crashing into the ceiling or floor after a few yards. I had to demur, and I never got another chance to display my prowess.

I located in our basement a few pages of memos written by me or Sheree about the installation. Kate had written notes in the margins. At a distance of thirty years (!) I could not understand the details of what was being discussed, but it was evident that I was trying to juggle a large number of balls at once. However, the use of the test system and the attitude of some managers made it seem like the balls were all coated with fly paper.

At some point in 1991 Bergner’s agreed that we had met the terms of the contract, which, by the way, was TSI’s simple version with only a few amendments. They made the last payment and also indicated that they also wanted to prepay TSI’s software maintenance for, I think it was, a year. They asked us to send them an invoice for this, but they wanted the description to be something like “Miscellaneous programming projects”.

The proverbial wolf was at TSI’s door again, and we had never turned down a check. So we did what they asked.

Bergner’s also approved quite a few enhancements that TSI had quoted. These projects were not covered by the original contract. So, I was still very busy with writing and installing all of the new code.

We used part of the money to hire Tom Moran to help with marketing. His role at TSI is discussed here. Perhaps I should have hired a programmer instead. I was more confident in my ability to produce an abundance of good code than my skill at closing sales. Also, I could not afford to devote the time necessary to train a programmer.

Bankruptcy: By August of 1991 Bergner’s had not sent TSI any checks in several months. We learned that the company had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. My recollection is that they owed us more than $10,000. We had no experience with this; none of our previous clients had ever done this.

Dan told me on the phone that Bergner’s would not be allowed to pay any invoice that was received prior to the default date and was still open. I realized immediately that they must have suspected that this was coming. That “miscellaneous” check was done that way so that we would be obliged to provide support for programming projects that they never paid for.

I wrote them a letter that said that we intended to apply the money from the miscellaneous check to the projects that we had delivered but they had not paid for, and we would begin to bill them for software maintenance. The Senior VP of advertising, Ed Carroll3, was furious at me personally. Dan Stroman called me about the situation. He said that I didn’t know who our friends were.4 Well, he might have been a friend, but I don’t think that many people at Bergner’s qualified for that distinction. I told him that our legal advisers (Me, Myself, and I) said that money given on deposit like that could be applied to open invoices. Dan did not respond to that. Instead, he asked if he wanted us to continue as a customer. I told him that I wanted them to become a paying customer.

I don’t remember the details of the rest of this episode. We continued to support the users at Bergner’s. They asked for a few more projects. We felt compelled to bill them at higher rates to try to make up for the money that we had lost.

I learned later that much of the retail advertising community considered Ed Carroll a sleazeball. What his advertising department did with that invoice was probably illegal or at least against company policy. He resented that what I proposed would make him look bad.

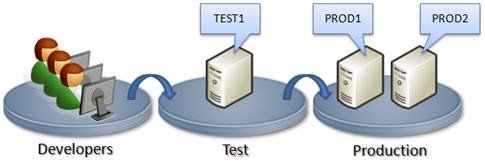

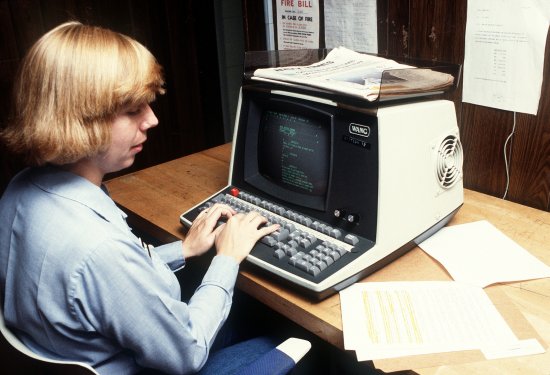

Test Environment: I found a letter dated May 13, 1992 that Kee-Huat Chua sent to TSI. It began with these two sentence fragments.

As you are aware of PAB’s intention to set up separate program environments for the AS/400 system. What it entails: one environment for intensive testing by users and one environment for developer/programmer to perform units [sic] test on the program module(s).

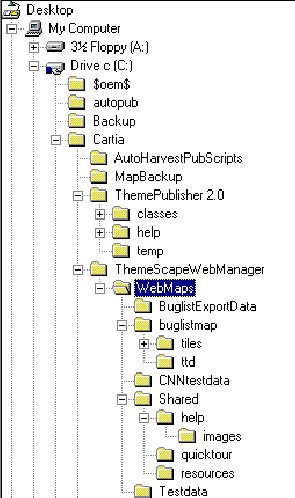

It then describes electronic forms that we needed to fill out before we made changes to the system. After we sent the form to him, he would copy the entire production library and the entire data library to the test environment. When this would happen is not designated in the letter. It could not be done if anyone was using the system. So, presumably it would be done at night.

After the libraries were duplicated, we would be allowed to sign on and implement the changes. We were also supposed to test them and send him a memo documenting that we tested them.

I guess that the users would then test them, but the letter does not mention it. It also does not mention how the changes will get into the production environment.

However, it does emphasize (in bold print, capital letters, and underlines), “NO COMPILING OF PROGRAMS ALLOWED DURING OFFICE HOURS UNLESS UNDER SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES; when making program modification.” Those special circumstances are not described.

Kee also included a list or reasons why this approach would be good for “TSI/Programmer:”

– To better perform & concentrate on their development.

– Less interruption and delay for development tasks.

– Secure production application: AdDept.

Although I considered this additional requirement a breach of our contract, I did not feel that I could refuse outright. I was sure that no matter what the missing details were, it would slow down our delivery of projects that they had requested by 50 percent or more. It also pretty much excluded them from ever getting new releases of our software.

This time Dan called me. I told him that we could have done it using test libraries from the beginning, but the project would have been hopelessly behind schedule if we had. He replied that he thought that that was what I would say.

I didn’t say this to Dan, but I also knew that this approach guaranteed that we would be doing a lot of extra work for which we would not be compensated. I cannot imagine who would really benefit from this. The alleged benefits for Bergner’s were equally bogus:

– To stabilize the “live”/production system both in the short run and the long run.

– To adhere with PAB’s standard of implementing computer systems established by Management Information Systems

– To encourage more users involvement with the implementation of the application.

I was mostly thankful that they did not come up with the idea of inserting this guy from the IT department between us and their system while we were still working on the base system specified in the contract.

This was a good example of why it always took IT departments ages to develop and install new software and why so many companies ended up outsourcing the IT department itself. My shoot-from-the-hip approach admittedly required some pain and frustration for a short period of time. However, it had worked extremely well in the ad agency environment, and it would also eventually prove effective in many other retail advertising departments.

Documentation and Ease of Use: Macy’s East’s long and involved contract did not require TSI to provide written documentation of how the programs worked. Although they demanded a commission for any AdDept systems sold in the first year after it was signed, they considered the whole project a custom job.

I no longer possess a copy of our contract with Bergner’s, and so I cannot check on whether it specified anything about documentation or not. I doubt it. Producing a user’s handbook that covered every eventuality of every aspect of the system would have been an overwhelming undertaking that got worse with every program change or new module. Instead, I made a conscientious effort to try to make the system fairly easy to use.

- The layout of all of the screens was consistent.

- The top three lines of data entry screens described the purpose. The screen number was in the upper right corner.

- If a new item was being created, the word “New” was also in the upper right corner, and it blinked.

- If the item already existed, the user ID, date, and time of the creation and last change were displayed.

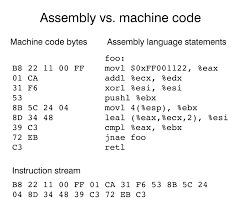

- All binary fields required the entry of Y or N. The 5250 standards used by all of the terminals and PC’s did not support check boxes.

- The options for all fields that would have had radio buttons on a GUI (graphical user interface)5 were listed on the screen.

- Two function keys were available at all fields that were verified against the database. F2 produced a detailed description of the field. F4 called a program that allowed the user to list and from the existing entries. Exiting these programs returned the user to the original screen with the cursor position maintained.

- All dates were entered in the form MMDDYY.

- All fields were verified when the Enter key was pressed. Any entries that were not valid were highlighted, and the cursor was positioned there.

- The format for all reports was as consistent as possible. The report number was almost always in the upper right corner.

- A list of the names of the most important tables and their key fields was provided for querying purposes. The names of the fields was consistent from table to table.

The biggest gripes were the lack of a user handbook and that the system was not “intuitive”. I considered trying to write a handbook, but I could not figure out a way to do it. Furthermore, I could not even start on it until all the programming required in the contract had been completed.

In all honest, I have never seen a system that was intuitive. The text-based user interface, which the only thing IBM provided at the time, probably seemed difficult to people who had never learned the keyboard.

I thought of a few ways to provide better documentation later, and we provided them to both new and existing clients. By then, however, Bergner’s had decided to try to find a different system.

Camex Interface: We were not the only software developers who felt Bergner’s wrath. When the AdDept installation began, Bergner’s produced its ads using Camex software on very expensive workstations from Sun Microsystems. Macy’s East did, too. Both of them wanted Camex to work with us for a two-way interface between the two systems. The story of how this project never got off the ground is recounted here.

Epilogue: The story of the installation has at least four epilogues:

- I think that after the bankruptcy brouhaha Bergner’s hired Gary Beberman, who had done a fantastic job as our liaison at Macy’s East, to help them. He called me about it. I told him that they had a good system installed, but we did not get along with some of the people there. I told him about the restrictive process that IT had set up for me to use. He was sympathetic, but he had no advice about how to turn around. He also warned me not to use Bergner’s as a reference account.

- Bergner’s advertising department tried unsuccessfully to replace AdDept for years, maybe even decades. I went back there for something some time in (I think) 1992. Joyce told me that they now had two systems, a pretty one and an ugly one. She said that she preferred the ugly one that worked.

- Bergner’s emerged from bankruptcy in 1993. They paid us pennies on the dollar. In 1998 the company, then known as Carson’s, was acquired by Proffitt’s Inc., which later became Saks Inc. All of the other Saks Inc. divisions used AdDept. Carson’s was merged with Younkers and Herberger’s, which both had successfully used AdDept. The resulting entity was called the “northern division”. Saks Inc. sold the division to the Bon-Ton in 2005, which closed down all 267 stores in 2018. During that entire disastrous sequence of events Ed Carroll ran the advertising department in Bergner’s. Carson’s, the northern division of Saks Inc., and the entire Bon-Ton.

- Some time early in the 2000’s I unexpectedly ran into Ed and Sheree (?!) at Saks Inc. in Birmingham, AL. Steve VeZain, who was in charge of the corporate marketing group, had asked me to come there for some other reason. Sheree was cordial to me, but when Ed saw me he barked, “What are you doing here?” More about this event is documented here. I never saw Dan Stroman again. I have no idea what happened to him.

Miscellaneous: Here are a few things that I remember about the installation:

- Dan and his wife had Sue and me over for supper on evening. She was a big University of Wisconsin fan. I remember her saying “How could you not love Bucky Badger?” I thought that Bucky Badger was ridiculous then. I have subsequently learned to hate him. The Stromans’ house was on a large pond. Dan had a boat. I don’t know why, but he revealed to me that he had had a vasectomy.

- Bergner’s insisted that I stay at the Mark Plaza Hotel when I was in Milwaukee. It had a doorman. He held the door for me even though I always had a free hand. I guess that that was his job, but it annoyed me. I have always hated it when people offered an unsolicited service and then expected a tip.

- One evening I tried to get some work done in TSI’s office, where I had “passed through” to Bergner’s system. After a while I became too drowsy to be productive. So, I intended to end my remote session. Unfortunately I keyed in PWRDWNSYS on a command line rather than ENDPASTHR. I accidentally shut down their system! I had to call the IT support line in Milwaukee and talk someone through starting it up again from the system console.

- The German food in Milwaukee was unbeatable.

- One day Dan Stroman, a guy from production whose name I don’t remember, and I went to lunch at a Thai place. I didn’t think much of it.

- I had fun jogging down by Lake Michigan in the evenings.

Failure: This entry has made me think about the nature of failure.

For about thirty-five years I designed, wrote, implemented, documented, and supported software systems. In the fifteen-year period that we actively marketed AdDept, we had thirty-five installations. Of all of those, the only one that I would characterize as a failure was the one at P.A. Bergner & Co.

I probably made mistakes. I tried to work on everything at once. I wanted to provide each stakeholder in the department with something to show that we were making progress.

Perhaps I should have insisted on doing one media at a time. Would Bergner’s have accepted that strategy? Who can say? They put a lot of pressure on us to get the entire project delivered. They seemed to have underestimated how much new programming they wanted. I am certain that I never said that we had already written software that was not actually working, but we were definitely trying to be optimistic. We desperately wanted the job. Maybe some statements that we made got misinterpreted.

I often took the “one area at a time” approach in other installations. We usually started with ROP and quickly achieved successful faxing of insertion orders and printing of schedules. That served as a confidence booster. If we had achieved important objectives quickly, perhaps no one would have suggested that wretched test environment. That approach would probably have also eliminated the weekly committee meetings. If my reports had been to one manager at a time, I would have been more careful in my comments.

In some future installations I designed one-time programs to help with the initial loading of tables by reading in user-supplied spreadsheet files. It did not occur to me to try this at Bergner’s, and no one suggested it. I am not sure that they actually had any files that I could have used.

I learned my lesson. In all subsequent AdDept presentations, I emphasized what I called “our dirty little secret”, to whit, the biggest factor in determining the success of an installation was the person who acted as liaison. I also took pains to specify what precisely the liaison’s responsibility and traits should be.

I also recognized that I should never have put in writing anything even slightly derogatory about a third party. Thereafter I always assumed that everyone would read every word that I wrote.

I learned one other lesson from this experience. I needed to investigate prospective clients more closely. From then on I asked prospective clients why they had decided to pursue automation of their advertising department at this point in time.

I can’t be too hard on myself, however. I don’t know of anyone else who managed to automate two advertising departments of large retailers. Over the years I installed thirty-five AdDept systems.

1. I never saw Dan Stroman again. I have no idea what happened to him. I suspect that he must fallen out of Ed’s favor. He may have been blamed for selecting TSI to design and implement the administrative system and for the collapse of the Camex interface project.

2. Sheree (pronounced like Sherry) Wicklund now goes by Sheree Marlow. Her LinkedIn page is here.

3. Joyce Nelson worked for the company until 2004. Her LinkedIn page is here.

4. Ed Carroll, one of the very few people in my life who really hated me, died in 2016. His obituary is here.

5. IBM did not provide OS/400 with a real GUI until more than a decade later, and even then what they suggested was slow, resource-intensive, and lame compared to what people were accustomed to on PC’s and Macs. TSI’s screens maintained the same format throughout the history of the company because we never found a way to convert the hundreds of screens that we had to produce something that was reasonably attractive. The approach that came closest was to write everything over in a language that used CGI for HTML files. That was how AxN worked.