Transition. Continue reading

In June of 1996 my dad and I made our first and only road trip together. The primary purpose was to help me decide between the University of Iowa and the University of Michigan.

Our first stop was in Detroit, where my dad introduced me to Howard Finsilver1, a sales agent for my dad’s employer, BMA, and his son, Sandy, who was my age and planned to attend U-M in the fall. I spent some time with Sandy and a group of his friends from (I think) Mumford High. At least one of them was also going to U-M. Then (as now) most good students in the state hoped to attend U-M. In some parts of the country many top students disparage state schools, but not in Michigan. Sandy and all of his friends were quite impressed that I had been admitted as an out-of-state student.

We shot some pool in the basement of the house of one of the friends. Someone then drove Sandy and me around Detroit to show me some of its highlights. I don’t remember details, but I doubt that the Chamber of Commerce would have agreed with the sites that they chose.

On the next day dad and I drove the thirty-seven miles to Ann Arbor to talk with a professor from the math department. I don’t remember the specifics of the conversation, but I absolutely fell in love with the town, the campus, the entire atmosphere. And that was before I ever set foot in the football stadium. Just about everyone who visits the town in the spring or summer has this reaction.

On the way to Iowa, we stopped somewhere in Indiana to play some golf. I don’t think that either of us enjoyed the round much.

The last hundred or so miles before we got to Iowa City we saw almost nothing but corn on either side of the road. The professor we talked to at the university made a pretty good case, but I had already decided that I wanted to attend the University of Michigan.

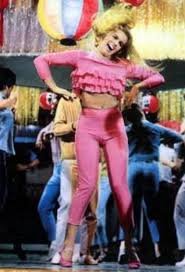

My dad was fairly often involved in providing entertainment for some of the company’s salesmen and regional sales managers when they came to the home office in KC. In the middle of July one of the salesmen had brought two of his sons with him on such a visit. One was close to my age and the other, who also worked as a BMA salesman, was in his twenties. I think that their last name was Roberson. BMA bought three primo tickets for me and the two sons for the Starlight Theater, an outdoor venue in Swope Park that showed musicals in the summer. The show was Bye-Bye Birdie, and it starred the rock group Gary Lewis2 and the Playboys. This occurred at the height of the group’s popularity. The group had one big hit, “This Diamond Ring”, and a number of other songs that did well on the charts.

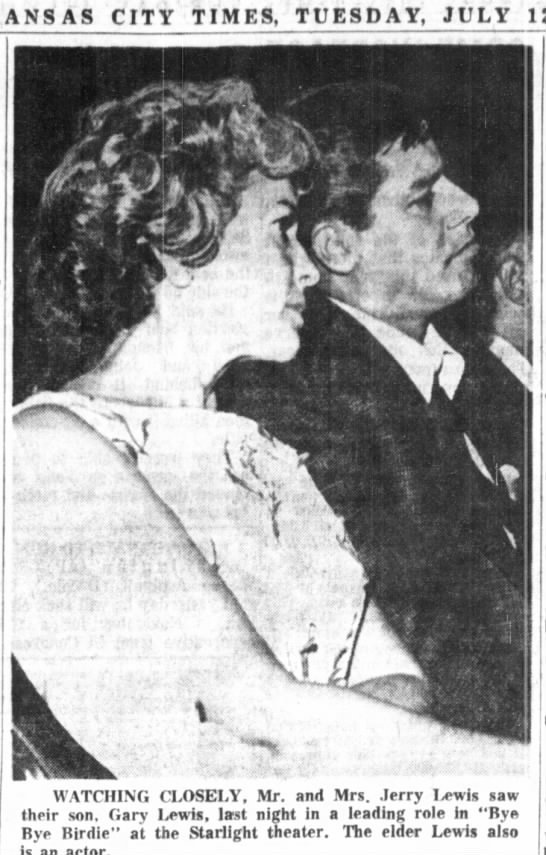

Gary Lewis’s father was the comic actor, Jerry Lewis. On Monday, July 11, Jerry and his wife and entourage were in KC for their son’s opening night. Believe it or not we were in the fifth row right in the middle. Jerry Lewis was seated in the fourth row between his wife, who did not utter a word all night, and another woman who must have been an agent or something. Jerry Lewis himself sat a few inches from my right knee.

As soon as Jerry Lewis arrived, he consulted privately with another staff member who was seated on the other side of Lewis’s wife. The staffer left for a few minutes and then returned with a large paper cup that was quite different from the kind available at the concession stand. Lewis sipped from it until intermission. Before the play started a few young people came up to ask for his autograph. No dice. The staffer who brought the drink did not let them get close to the star.

During the first few minutes of the performance J.L. tried to record the sound. He had great difficulty operating the recording device. The results of his efforts were a snake’s nest of tape around his feet and a torrent of blue language, the likes of which I would not hear again until I took part in basic training at Fort Polk in 1970. He abandoned the recording project somewhere before intermission.

At intermission J.L. and the staffer exited through a door that was not accessible to the public. They returned just before the play resumed. J.L. was fidgety and generally disruptive throughout the rest of the show. He downed another large paper cup of the mystery beverage during the second half. The Robersons told me that they could smell alcohol.

The play itself was OK. The rest of the actors were fine. I am not a big fan of musical comedy, but I had really liked the story when I saw the movie with Ann-Margret3. Gary Lewis was not believable as a teen dreamboat, and his rendition of “One Last Kiss” was almost laughable, IMHO. The group then played “This Diamond Ring”. They might have also played one or two other songs. There was no screaming from teenage girls in the audience.

At the end the Robersons asked the staff lady politely for autographs, but Jerry Lewis wanted only to get out of the theater immediately. He was in a very bad mood.

My opinion of Jerry Lewis did not change much. I thought that he was a self-centered obnoxious jerk both before and after this occasion. He pretty much ruined the event for everyone within fifteen feet of him.

I don’t remember what I did for the rest of the summer other than mow lawns and play golf. I don’t recall a job.

In late August my parents drove me and some of my belongings to Ann Arbor. Jamie probably came with us. I don’t remember much about the trip except my eagerness to get on with the next phase of my life. Of course, I was also a little nervous.

The University had notified me that I had been assigned to 315 Allen Rumsey4 House in West Quad. We drove there and met the third-floor RA, Jim Krogsrud, whom everyone called Gritty. Because classes did not begin until the following week, almost no one had moved in yet. Nearly all incoming freshmen had attended the week-long orientation period during the summer. I was allowed to stay in room 315 while I attended the orientation.

Gritty explained that all the rooms were doubles, but three people had been assigned temporarily to room 315. He said that he was sure that this would be promptly resolved. The family helped me carry my stuff up to the room. Then I said good-bye to them, and they drove off into the sunset.

Gritty asked me a few questions, one of which was whether I played bridge. He was very happy to hear that I did. He and Andy, the house’s RD, liked to play, and they were looking for opponents. He also explained how the laundry and other aspects of life in the dorm worked.

They must have served meals in the West Quad dining room for the few of us who were there that week. I don’t remember having to find restaurants or walk to another dorm.

After breakfast on the day after my parents left I met with my orientation group. Our group leader was a guy. I don’t remember his name. The members of our group were all enrolled in the college of Literature, Science, and the Arts. One of the first orders of business was taking language placement tests. LS&A had a two-year language requirement. I was preparing myself mentally for the Latin test when the group leader told me that he had received a note stating that I did not need to take the test. He said that he had never heard of such a thing. He advised me to take the test anyway.

I showed up for the Latin test. It consisted of a multiple choice grammar test and a sight translation of some lines from Vergil. It seemed pretty easy to me; I was the first person to leave the test room.

I later learned that my 790 on the SAT’s Latin achievement test was the reason why I did not need to take the test. However, I did not get any academic credits for skipping the four semesters of introductory Latin. I did, however get three credits for Advanced Placement English and eight for AP math.

A few days later I got to consult with my academic advisor, who was, of all things, a biology professor. I only met with him for a few minutes once per semester; I don’t recall his name. He told me that I should have been invited to the honors program. He made a few phone calls, after which he told me that I was now in it. He then penciled in a schedule of four classes for me:

- Math 195. There were three math sequences, two for honors and one for others. 195 was the first class for the higher ranking of the two introductory honors math sequences.

- Great Books, an honors class in the English department.

- Chemistry 103, the introductory class for students who did not take chemistry in high school.

- Russian 101, which would meet a requirement for math majors—two semesters of Russian or German.

- Two semesters of phys ed were also required for freshmen. I picked the course in golf for the first semester.

However, when I got to the actual registration, I discovered that all sections of Great Books were closed. So, I added a 300-level Latin class that focused on Cicero’s orations. It was only a two-hour class, but I already had eleven credits under my belt from the AP tests.

I felt pretty good about this schedule. The subject that worried me the most was chemistry. I figured that I would need to work harder than I did in high school, but that was not really saying much.

While at registration I came across a girl distributing flyers for the U-M debate program. On Tuesday, the day before classes began, the team was holding an open house for anyone who was interested in debate. Based on my lackluster high school career, I had little expectation of debating at U-M, but I took the flyer anyway.

I was on my own in Ann Arbor. I knew almost no one. Only a handful of guys5 had moved into Allen Rumsey House yet. The only other person on the third floor of AR was Gritty. I probably should have made an effort to meet people in my orientation group—in all likelihood most were from other states with no friends in Ann Arbor. It never occurred to me. That’s the way I am.

I spent a great deal of time in my room that first week playing one-at-a-time, once-through-the-deck Klondike solitaire. I recorded all of my scores. I also read quite a bit. I had an AM-FM radio, but no other electronics.

In 1966 all freshman students were required to live in dorms. The residence halls were called “houses.” The men’s houses were in three groups. The houses in East Quad and West Quad had only males. South Quad had men’s houses and women’s houses. The remainder of the houses for girls were on the northeast side of central campus in the area known as “The Hill”.

Having been constructed in the thirties, Allen Rumsey House (#1 in the above photo) was the oldest dorm on campus. Little had been done to modernize it in the ensuing decades. With approximately one hundred guys, it was also the smallest house.

Having been constructed in the thirties, Allen Rumsey House (#1 in the above photo) was the oldest dorm on campus. Little had been done to modernize it in the ensuing decades. With approximately one hundred guys, it was also the smallest house.

On the east side was a corridor between AR and the International House (#3). Wenley House (2), which was almost as old as AR, shared a wall on the west. South Quad was to the south, on the other side of East Madison St. On the north side was a courtyard. Two doors on the other side of led to the central section of West Quad, which contained the cafeteria and a lounge area. A third door led to the bowling alley (#4) and a shortcut to the Michigan Union (#5) and the rest of the central campus, the site of all my classes.

I quickly found the lounge on the first floor of Allen Rumsey House. It had comfortable chairs, a trophy case, a rug, and a piano. The house subscribed to the Michigan Daily, the Ann Arbor News, and a few magazines, including, I later learned, Playboy.

Downstairs was a game room with a small pool table, a ping pong table, and a free juke box! A section of this room and a separate room had televisions and chairs. Both TVs were 19″ black and whites. Next to the small TV room was a study hall that AR shared with Wenley House.

I eventually got up the nerve to shoot pool with another lonely guy named Dan Schuman. He had no hair anywhere on his body, and he was very cynical. We got along great. We played eight-ball. Although he was a better shot than I was, he was unaccustomed to an opponent who always left the cue ball pinned to a rail. The games were long and, for him, frustrating. I usually won.

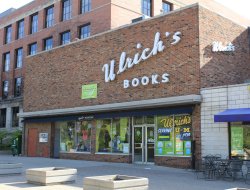

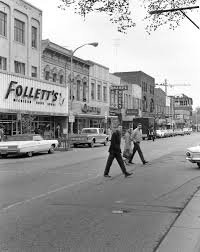

Used books for every class could be purchased at the two big bookstores, Ulrich’s and Follett’s. Ulrich’s was on South University; Follett’s was on State St. I bought the textbooks for Russian, Math, and Chemistry at one of them. The Latin class had no textbook.

I think that classes started on the Wednesday after Labor Day, September 7. By Tuesday I knew that my roommates in 315 were Ed Agnew from Bloomfield, MI, and Paul Stoner from Adrian. Across the hall in 314 was Dave Zuk. His assigned roommate did not show up. So, Gritty had us draw straws or something to decide who would move across the hall. Paul was selected.

This was good news and bad news. I did not like Ed very much, but I did like his stereo. His taste in music did not accord with mine or anyone else’s that I have ever met. He loved “big band” music, and his all-time favorite recording was the soundtrack from Victory at Sea. However, he did let me use his stereo when he was not around, which, I soon discovered, was essentially every afternoon and evening.

I did not bring any of my records, but 1966 was an exceptional year for popular music. I spent most of my savings on albums. That is to say, I bought three or four records.

Our room was on the north (courtyard) side. I claimed the bed on the west side, leaving the one on the east side for Ed. Two big windows on the north side were fronted by a large double desk with two chairs. The east wall was an external wall, but there were no windows. We each had a dresser. Maybe we shared a closet. There was a sink with a mirror over it on my side. There was also a slot over the sink for disposal of dull razor blades. I have never seen anything like it anywhere else. I wonder how many blades were inside the wall. I used an electric razor in college. Each room had a plain wall phone. I don’t remember whether they allowed us to make calls on it or not. To get mail you had to walk to the center part of West Quad next to the cafeteria.

I attended the debate meeting in a room on the second floor of the Frieze Building, the headquarters of the speech department. About twenty people attended. We got to meet Dr. Bill Colburn and a couple of grad student coaches, including Jeff Sampson, who debated at Northwestern, a national power. Evidently there was no individual events program.

All of the new people filled out a form outlining our experience and interests, and then we watched a debate between two of the varsity teams. I thought that they were both horrible, and I was shocked to learn that they were U-M’s best teams.

I was paired with a fellow from Portland, ME, named Bob Hirshon. They told us that the topic was “Resolved that the United States should substantially reduce its foreign policy commitments.” Bill and Jeff privately made it clear that they were excited that Bob and I were interested in debate, and they wanted us to represent U-M at the Michigan Intercollegiate Speech League (MISL) novice tournament in October. We would be debating only on the negative. I was second negative.

I was shocked to be on the receiving end of all of this attention. I was uncertain whether I would be able to handle it, but I agreed to try. So did Bob.

1. Howard Finsilver died in 2005.

2. According to Wikipedia Gary Lewis was a better drummer than a singer. His voice was overdubbed on the recordings of his hits. I was surprised to learn that he was drafted the following January and served in Vietnam and Korea. After his hitch in the army he stayed on the fringes of show business with new incarnations of his band. In 2020 he was still performing at age 74.

3. Just to be clear, Ann-Margret appeared in the movie; she wasn’t my date.

4. Ann Arbor is named after Ann Allen and Ann Rumsey, early settlers of the town.

5. In 1966 there were no coed dorms at U-M. In fact, female students were not even allowed to enter Allen Rumsey House except under special circumstances.