A very memorable day. Continue reading

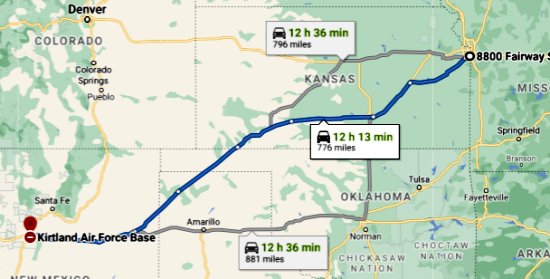

The announcement that the three bases—Kirtland AFB, SBNM, and Manzano Base—were being merged was made on Thursday, July 1.

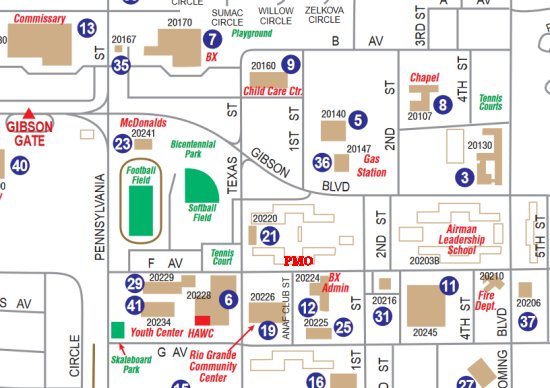

Capt. Dean must have known that this was coming. He had already scheduled an all-day party for MPCO with free food and free beer at the softball field on the other side of E. Texas St for Sunday, July 4, Independence Day. I don’t remember what time the outing started or ended. It seemed like a very big celebration. Lunch might have been served or supper or both. All the MPs were invited. I don’t remember anyone else being there. One of the patrols must have reported for the day shift, and one must have manned the swing shift that day. This makes me think that the party must have started well before 2:00 and ended well after that time. Capt. Dean clearly wanted everyone to be able to attend.

Sunday turned out to be a beautiful day for a picnic. I don’t actually remember what it was like, but if had not been sunny, warm, and breezy, I certainly would have remembered it.

Since it was Sunday, I probably went to mass. There was only one chapel on the base that was used for all of the Christian services. The base chapel currently has masses on Saturday at 5 p.m. and on Sunday at 9 a.m. If I did not attend on Saturday evening, then I certainly went on Sunday morning. The services themselves were in no way memorable—I don’t remember the priest at all. On the other hand, if, for some reason I had not gone to mass, I would remember it. I was a good Catholic; I never missed mass.

I know that it supposedly came from the Land of Sky Blue Waters, but to me it tasted more like the familiar yellow waters.

At some point I ambled over to the baseball field for the party, which I remember as a rather low-key affair. Everyone was in civilian clothes. Capt. Dean may have given a short speech, but by and large it was unstructured.

I think that there was a softball game, but I don’t remember playing in it. The only thing that I clearly recall was that a very large amount of beer was provided. It was all in twelve-ounce cans, and it was all Hamm’s.

I probably drank a can or two. I definitely did not get drunk. I clearly remember the first time that I got drunk, and it was still a few years in the future. Others certainly drank more than I did, but I don’t think there were any incidents worth mentioning. All my recollections are very vague. I probably hung around with my friends. I am certain that I avoided the officers, the sergeants, and the other lifers.

The rumor mill was certainly running at maximum power. Talk centered on two things. In the first place, it was now pretty well established that draftees were going to be allowed to ETS early. How early? The most commonly heard period was six months. However, no one had yet been assigned a new ETS date. Someone at the party might have asked me how short I was. If so, I would have without hesitation answered 457 days. It would be presumptuous to subtract six months before it was official. The other topic of speculation was the takeover by the Air Force. When would it take effect? Would everybody ship out? Would we all go together? No, of course not. Were there other DNA bases we could go to? It turned out that there were, but not many knew this.

The rumor mill was certainly running at maximum power. Talk centered on two things. In the first place, it was now pretty well established that draftees were going to be allowed to ETS early. How early? The most commonly heard period was six months. However, no one had yet been assigned a new ETS date. Someone at the party might have asked me how short I was. If so, I would have without hesitation answered 457 days. It would be presumptuous to subtract six months before it was official. The other topic of speculation was the takeover by the Air Force. When would it take effect? Would everybody ship out? Would we all go together? No, of course not. Were there other DNA bases we could go to? It turned out that there were, but not many knew this.

The combination of the two sets of rumors was enticing. If my new ETS was in April, even if orders came in July, I would have less than2 nine months at the new posting. Usually overseas hitches were for at least twelve months. So I would get paid for travel time, but I would still be stateside.

I think that the gathering lasted until dark or maybe even later. I retired to my room fairly early. Monday was a work day1. I was probably asleep by 10 p.m., and I slept soundly, at least for a few hours. I was roused from sleep—I did not look at the clock—by a loud roaring sound. It kept up for a few minutes, varying in intensity from softer to exceptionally loud.

By this time I had been on the base for four months, and I had become somewhat inured to strangeness. Also, I am a sound sleeper. When the roaring subsided, I rolled over and went back to sleep.

Time passed. Feeling the need to return some Hamm’s to the Land of Sky Blue Waters, I awoke again. This time I did look at the clock. It was 2:30. I went out in the hall in my underwear and was more than a little surprised to see tire tracks on the linoleum. I have never done much research on the subject of tire tracks, but since the hallway was only a few feet wide, I deduced that someone had probably ridden a motorcycle up and down the hallway. That also explained the roaring.

Time passed. Feeling the need to return some Hamm’s to the Land of Sky Blue Waters, I awoke again. This time I did look at the clock. It was 2:30. I went out in the hall in my underwear and was more than a little surprised to see tire tracks on the linoleum. I have never done much research on the subject of tire tracks, but since the hallway was only a few feet wide, I deduced that someone had probably ridden a motorcycle up and down the hallway. That also explained the roaring.

I looked up and down the hallway. Everything seemed to have calmed down. I turned right and walked toward the latrine. Uh-oh. Even without my glasses I could tell that the fluorescent light fixture on the wall by the latrine was hanging limp and dark at an angle approaching 90° from its usual position. Evidently the shenanigans at the post-party had gotten a little out of hand. No one was in the latrine. I took care of business, exited, and walked back to my room. Just before I reached the door I heard a very unusual sound—more startling even than the roar of a motorcycle. It was giggling, high-pitched giggling. So, either some guys had obtained some helium and mixed it with nitrous oxide, or there were girls in one of the rooms.

It was not my business, and it was not my problem. I went into my room and quickly returned to Dreamland. Throughout my life I have enjoyed the ability to get to sleep almost at will and to sleep for as long as I want. I had an alarm clock in the army, but I was almost always already awake when the alarm went off.

My job in the Law Enforcement office, gave me a different schedule from that of everyone else in the second platoon. I had the latrine to myself for the three s’s with which every soldier is expected to start the day. I then went to work. Throughout the morning the banter, if any, was about the previous day’s party, which all four of us—Capt. Huppmann, Sgt. Edison, SP4 Duffy, and myself—had attended. I said nothing about what I had seen and heard in the hallway.

At some point that day the news started to filter through about what had happened in the barracks the previous night. Neither Capt. Huppmann nor Sgt. Edison asked me any questions. I don’t think that they realized that I still lived alongside the guys in the second platoon. To the best of my knowledge neither of them was involved in the official investigation. Neither SP4 Duffy nor I had anything to do with it.

I learned more after work on Monday. Everyone on our floor—except for me—had been called in for questioning by the investigators. I never did find out who ran the original inquiry. Eventually it was turn over to experienced detectives who worked for the Army.

Here is all that I learned. It is all second or third or nth hand.

- Three guys were pulled from duty and confined to the base for the duration of the investigation—Tom Bedell (a good friend who lived down the hall from me), Bob Willems (my friend from AIT), and Paul Calandra.

- Three young girls, children of lifers who lived on the base, were somehow identified as being in the barracks on Sunday night.

- Drugs were somehow involved.

- The most alarming thing was that the girls were still missing.

During the week there was a lot of discussion, but no additional information. I kept going to work every morning. The three suspects were interrogated each day. I did not share with anyone in the Law Enforcement office anything that I heard in the barracks. I puzzled over why the investigators had not asked to talk with me. It wasn’t until several years later that I figured out what must have happened. The investigators probably requested a list of people who lived on our floor. Instead of using a room-by-room list of the guys in the barracks, someone found a duty roster for the second platoon and left out the people who lived off-base. My name would not have been on the roster, and therefore it was not provided to the detectives.

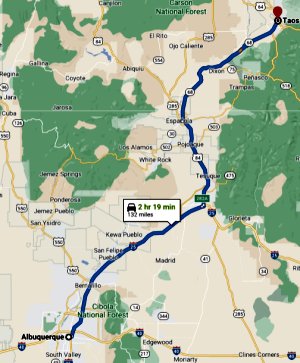

The next weekend the girls finally returned to their homes. Fearful of being punished by their parents, they had somehow made their way to Taos, not exactly a suburb of Albuquerque, to stay with a guy whom one of them knew. Their reappearance was a big relief to my three friends. The guys were still in a lot of trouble because at least one of the girls was underage, but nobody could any longer consider them murderers.

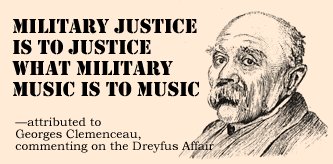

Bob Willems was given an Article 15 (non-judicial punishment) for either marijuana use or distribution. I know that he was demoted one rank, which would eventually cost him a few hundred dollars. He was also confined to the base for another month or two, and he might have been fined.

Everyone except the lifers considered this an outrageously strict sentence for something that transpired literally every day in the barracks. God only knows how much pot was smoked that night in other rooms. If Capt. Dean or whoever determined the sentence imagined that there would be a deterrent effect, he was wrong. It might have worked if lifers moved into the barracks, but none did.

Everyone except the lifers considered this an outrageously strict sentence for something that transpired literally every day in the barracks. God only knows how much pot was smoked that night in other rooms. If Capt. Dean or whoever determined the sentence imagined that there would be a deterrent effect, he was wrong. It might have worked if lifers moved into the barracks, but none did.

Bob could have appealed the Article 15, but only if he submitted to a court martial. He accepted the punishment.

On the other hand, Tom and Paul were offered a deal. They could either be court-martialed on both the drugs and statutory rape charges or they could accept “general” (sometimes called “other than honorable”) discharges from the Army and go home. This would eliminate not only the active duty requirement but also the three or four years required in the reserves.

Both guys thought this over for about one second and accepted the discharges. I am quite sure that virtually all draftees and many guys who enlisted in 1970 would have accepted a general discharge on day 1 of their time in the Army. I certainly would have. The only time that anyone has ever asked me about my discharge was when I bought my Honda in 2018. The salesman at the dealership asked me to produce the paper in order to qualify for the veterans’ discount.

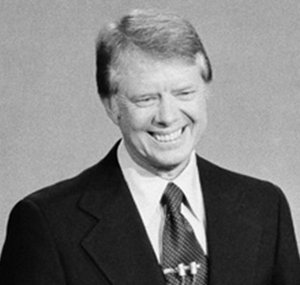

In 1971 there were five levels of discharges from the military: honorable, general under honorable conditions, undesirable, bad conduct, and dishonorable. The latter two were part of the penalty after being convicted in a court-martial. In 1977 President Jimmy Carter instituted a program whereby people who received less than honorable discharges could apply to a special board for the purpose of upgrading them to an honorable discharge. I don’t know whether Tom and Paul went through this process, which in any case would not have qualified them for veterans’ benefits.

In 1971 there were five levels of discharges from the military: honorable, general under honorable conditions, undesirable, bad conduct, and dishonorable. The latter two were part of the penalty after being convicted in a court-martial. In 1977 President Jimmy Carter instituted a program whereby people who received less than honorable discharges could apply to a special board for the purpose of upgrading them to an honorable discharge. I don’t know whether Tom and Paul went through this process, which in any case would not have qualified them for veterans’ benefits.

No one was ever charged with vandalizing the hallway in the barracks.

1. I looked this up. In 1971 the nation celebrated Independence Day on July 4 even though it was a Sunday. July 5 was not a federal holiday that year.

2. I am pretty certain that this is correct usage. Although months are in a sense countable, a month is not a discrete measure of time. If I said 272 days, “fewer than” might be appropriate. If I had said 979,200 seconds, I would definitely have used “fewer than”, even though seconds are technically not discrete either.