MP Training at Fort Gordon Continue reading

My orders instructed me to report to Fort Gordon, GA, another military base named for a Confederate general, for training as a Military Policeman. Fort Gordon is near Augusta. I flew to the Augusta airport from KC. Almost five decades later I can still remember the smell of the air around the airport. I don’t know what produced the stench

My orders instructed me to report to Fort Gordon, GA, another military base named for a Confederate general, for training as a Military Policeman. Fort Gordon is near Augusta. I flew to the Augusta airport from KC. Almost five decades later I can still remember the smell of the air around the airport. I don’t know what produced the stench—something industrial, i think. It was almost overpowering.

I was assigned to E-10-4: echo company, tenth battalion, fourth MP training brigade. I was surprised to find that, in our platoon at least, there seemed to be quite a few college graduates. I later learned that the minimum GT score for MP’s was 90. Our company in Basic had been roughly evenly split between draftees and guys who enlisted. Here almost everyone had been drafted.

We shared the mess hall and the training schedule with F-10-4, called “F Troop” by everyone including the guys who were in it.

I don’t remember the name of our platoon sergeant. He barely went through the motions of supervising, and he did no training at all. He spent most days in the rec room shooting pool while we were out training.

As in Basic, each squad had temporary corporals. The ones in Basic had just been guys appointed, apparently at random, by the drill sergeant. The ones at MP school had volunteered to spend a week or two after Basic being trained how to be a corporal. In exchange, if my memory is right, they were guaranteed a promotion to E2 (one stripe!) at the end of AIT.

Our squad’s pseudo-corporal was named Burt. I don’t remember his first name. He had enlisted with the intention of becoming an MP for life. He kept in his locker a leather-bound family bible that was at least three inches thick. He was very proud of it. He showed me once how it included pages to record marriages, births, and deaths. He told me that how much it cost, and the figure astounded me. I asked him why he did not buy a cheap bible and a spiral notebook for the family history part. He took my question seriously.

One of the other temporary corporals was named Junkker. He allegedly scored 160 on both GT tests. I never got a chance to know him very well.

Here is a list of the guys in my squad. I might have missed one or two people.

- Ken Wainwright went to Boston College. He knew two of my friends from high school, John Rubin and Pat Dobel, my first debate partner. They had both attended BC.

- Since Dawson Waites was a little chubby, he was designated as a “road guard”. Whenever the company, while marching to a training area, approached an intersection, the sergeant or officer leading us would yell “Road guards post!” Dawson and the other road guards had to run to the front to stop traffic. In the Army they often talked about the (Airborne) Ranger Shuffle. Dawson perfected the Forest Ranger Shuffle, which was slightly slower than a standard walking pace.

- Jerry White was a 6’9″ black guy who flew to Cincinnati every weekend to play semi-pro basketball. Since we had almost no free time during the week, the rest of us did not get much chance to know him very well.

- Bob Willems was from New Jersey. He went to Rutgers, the state university of New Jersey.

- AJ Williams lived in the Boston area and went to Bates College in Maine. He was the state champion in the mile run.

- Ned Wilson went tp Ohio State, but I tried not to hold it against him. He was married and kept to himself most of the time.

- Dave Zimmerman went to American University in DC.

As you might have guessed, we were assigned in alphabetical order. We had single beds (not bunks). Mine was between Dawson Waites’s and Jerry White’s. Aside from Jerry and Acting-Corporal Burt, we were a fairly homogeneous group of pretty well-educated draftees who were just trying to get through the next two years in one piece. It was pleasant to be able to have conversations about something besides toughness, girlfriends, and cars.

Rumors were slightly less prevalent than in Basic. Most centered upon our future duty assignments. About halfway through our training the chief cook at the mess hall disappeared. The rumor was that he had been caught selling meat on the black market.

One of the biggest differences between Basic and AIT was that we were actually graded. In theory it was possible to flunk. A couple of guys tried to fail the training, which would have got them assigned to some other MOS. My recollection is that we were required to score at least 700 out of 1,000 points. The last test was physical fitness. A guy named Walton had deliberately done badly enough that his total score was only 695. However, before they posted the total his “commander rating” had been improved enough to put him over the threshold. It was a little surprising that he even had a commander rating. He had gone AWOL once, and he absolutely refused to march in formation. He shuffled along behind us.

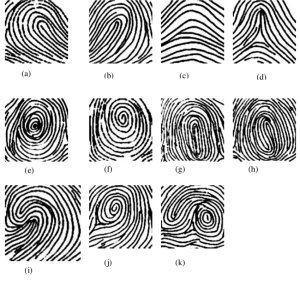

Some of the training classes were fairly interesting. They were all better than map reading in Basic Trainig. My favorite was learning about the various categories of fingerprints. My own set of ten, which I had never contemplated before, contained examples of almost every category. We also learned how to take prints using ink and paper.

Some of the training classes were fairly interesting. They were all better than map reading in Basic Trainig. My favorite was learning about the various categories of fingerprints. My own set of ten, which I had never contemplated before, contained examples of almost every category. We also learned how to take prints using ink and paper.

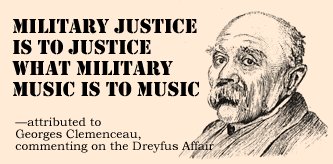

The military law classes were a joke, which was probably appropriate. After all, there is a famous book, which I have read, called Military Justice is to Justice as Military Music is to Music. The title comes from a quote from Groucho Marx, who probably stole it from Georges Clemenceau. Before presenting any material that would be on the test, the instructor loudly announced, “THIS IS IMPORTANT!!”

The military law classes were a joke, which was probably appropriate. After all, there is a famous book, which I have read, called Military Justice is to Justice as Military Music is to Music. The title comes from a quote from Groucho Marx, who probably stole it from Georges Clemenceau. Before presenting any material that would be on the test, the instructor loudly announced, “THIS IS IMPORTANT!!”

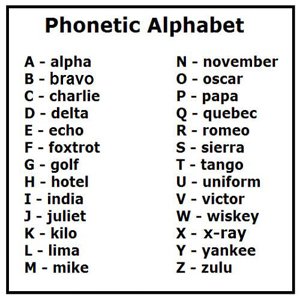

We also learned to talk on the radio. We had to memorize the Army’s phonetic alphabet (in which alpha, bravo, charlie replaced the Able, Baker, Charlie series that was used in World War II) and the ten-series (a la Broderick Crawford). We were also enjoined never to use the word “repeat”. Instead, you should say “say again”.

We also learned to talk on the radio. We had to memorize the Army’s phonetic alphabet (in which alpha, bravo, charlie replaced the Able, Baker, Charlie series that was used in World War II) and the ten-series (a la Broderick Crawford). We were also enjoined never to use the word “repeat”. Instead, you should say “say again”.

We did not have to carry weapons with us. The only time that they issued us M16s was when we went on bivouac, a camping trip that lasted a few days. The only weapon that we learned to use was the Colt .45 caliber handgun. There was a sharp contrast between this hand cannon and the rifle that we were all now familiar with. The M16 had almost no kick. The .45 would rip your arm off if you were not careful. Furthermore, those huge slugs were very scary. The trainers told us that if one hit you in the toe you would go down. The biggest difference was that it was MUCH easier to hit a target at 300 meters with an M16 than it was to hit one with a .45 that was ten times closer!

We did not have to carry weapons with us. The only time that they issued us M16s was when we went on bivouac, a camping trip that lasted a few days. The only weapon that we learned to use was the Colt .45 caliber handgun. There was a sharp contrast between this hand cannon and the rifle that we were all now familiar with. The M16 had almost no kick. The .45 would rip your arm off if you were not careful. Furthermore, those huge slugs were very scary. The trainers told us that if one hit you in the toe you would go down. The biggest difference was that it was MUCH easier to hit a target at 300 meters with an M16 than it was to hit one with a .45 that was ten times closer!

We fired these things a few times on the firing range before we were tested on our marksmanship. “Up and down-range” was constantly yelled at us. Unfortunately, it was always yelled in English, and that was not the mother tongue of some of the guys from Puerto Rico, particularly Private Manuel.

When the instructor explained how to hold the pistol so that the recoil did not brain you, Manuel evidently missed it. The first time that Manuel fired the .45 it kicked back and smacked him in the forehead. He was only stunned, but the gun made a big mark in his forehead that did not go away for weeks.

Another time on the firing line an instructor noticed that Manuel was doing something wrong. He approached Manuel from the rear and addressed him by name. Manuel spun around so that they were facing each other. Manuel’s .45 was pointed at the instructor’s head. The .45 was loaded, the safety was off, and a round was in the chamber.

The instructor calmly said. “Manuel: about face.” Manuel knew this command, and he turned back toward the firing range. The instructor, still behind him, then reached toward Manuel’s weapon and told him to hand it to him. Once he had the .45 in his hand, the instructor loudly informed Manuel what he had been doing wrong. He may have even made him do some push-ups.

Towards the end of the training we were given the chance to try to qualify with the .45. We took forty shots at targets, and an instructor kept score. Here are the details:

-

- The passing score was 300 out of a possible 400.

- The test had two parts. The first used standard bullseye targets with ten concentric circles. The innermost circle was worth ten points. The outermost was worth one. For this part of the test we were able to take our time, hold the weapon with both hands, and aim carefully. I think that ten shots were at twenty meters, and ten were at thirty meters.

- For the second part the bullseye target was replaced by three truncated life-sized silhouettes. This time we shot twenty times at thirty, twenty, and ten meters, and we had to shoot rapidly from different positions. The last few at ten meters were shot “from the hip” like a cowboy in a gunfight. Each hole in one of the silhouettes was worth ten points.

We all took our forty shots in the first round. A few guys who were experienced shooters qualified on that round. They were allowed to return to the barracks. The rest of us remained until we qualified, or they gave up on us.

Nobody from our squad qualified on the first try, but all the rest of the guys did better than I did. My score was only 68 out of a possible 400! I thought for sure that all three of my shots from the hip must surely have hit one of the silhouettes. They were only ten meters away, but I missed all of them!

For the second round a new rule was added. If you did not score at least 100 on the bullseye, you would not be allowed to shoot at the silhouettes.

I can proudly report that I did much better on the bullseyes the second time. I looked at my target and quickly added my score in my head. It was 80 or 81. I was thrilled. That was much better than the first time. I knew that I would not be allowed to shoot at the silhouettes in this round, but I now felt that I had some chance of qualifying in round four or five.

When the instructor came around to grade my bullseye, he informed me that I would “need to hit nearly all of the silhouettes to qualify.”

The words “nearly all” banged around in my head, but I gave the correct response, which was “Yes, sergeant.”

So, I was allowed to shoot at the silhouettes. Once again, I did much better. At the end I could see that I had hit one of the targets nearly half the time, and there were also four or five ricochets. The ricochets are easy to discern. Regular holes are round. Ricochets are much higher than they are wide because they have bounced off of the ground up toward the target at a steep angle.

One again the instructor surprised me. He looked at my targets and said, “Well, some of these holes look like they have two or three bullets in them. You qualified. Turn in your weapon.” He obviously knew about ricochets. Either he was extremely poor at arithmetic, or he just wanted to put an end to this as fast as possible.

Only a few guys qualified in the second round. The rest stayed at the testing area to go through the process again. The best part was that the guys who qualified in the first round learned when they arrived back at the barracks that they earned the privilege of being on KP for supper. By the time that I arrived with the second group, the KP roster was filled. We were actually left on our own, a very rare thing.

So, the Army allowed me to wear a ribbon touting my skill with the hand cannon. However, I knew in my heart that I was a terrible shot. I vowed never again to squeeze the trigger on one of those things. If I ever needed to use it, I would throw it rather than fire it.

We were supposed to learn how to drive a five-speed standard-transmission Jeep. We did have one class in it, but we were supposed to have two. They warned us that the Jeeps had very high centers of gravity. They said that we should NEVER drive faster than 35 miles per hour.

We were supposed to learn how to drive a five-speed standard-transmission Jeep. We did have one class in it, but we were supposed to have two. They warned us that the Jeeps had very high centers of gravity. They said that we should NEVER drive faster than 35 miles per hour.

Most of the guys got to do some driving. The guys who were familiar with standard transmission cars leapt at the chance to drive a Jeep. I never got to drive at all.

I suspect that Private Manuel, who had never operated any kind of car, set a new world’s record for driving the shortest distance before totaling a vehicle. The previous driver had left the Jeep in first gear with the brake off and the steering wheel turned hard to the left. Another Jeep was parked to his left and less than a foot in front. Manuel turned the key and his Jeep lurched into the other Jeep’s rear corner, which was armored. Manuel still had his hand on the key, and he kept turning until something important under the hood was dismembered, and the engine in Manuel’s jeep went silent forever.

Approximately three-fourths of us actually got to drive. Two drivers flipped their Jeeps because they went too fast around a corner. One was Manuel. I don’t remember if there were injuries. If so, they must not have been too serious.

We had to take a driving test. I flunked. They gave me an hour or so of personalized instructions in the evening, after which I passed easily. Subsequently all of my personal cars (except for the Duster that Sue bought) have had standard transmissions up until 2018, when it was no longer available. I did learn something in the Army.

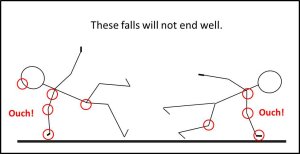

We had an interesting class in hand-to-hand combat. The first part involved showing us how to bodyslam an opponent. Since this technique is essentially useless outside of a professional wrestling match, they were actually teaching us how to take a fall without breaking any bones.

We had an interesting class in hand-to-hand combat. The first part involved showing us how to bodyslam an opponent. Since this technique is essentially useless outside of a professional wrestling match, they were actually teaching us how to take a fall without breaking any bones.

Our company was joined for this training by a small group of Marines. The instructors had a side bet on whether the first trainee to break a collarbone would be one of the 200 Army guys or the 14 Marines. The guy who bet on the jarheads won, but two of our guys also broke collarbones. In both cases the guys survived the first slam, but they both tried to break their falls with their hands. The instructors told both of them that if they did that again they would probably break something, but they could not help themselves.

It pretty much goes without saying that one of the guys who broke his collarbone was Manuel. They took him to the hospital, and we never saw him again. I don’t remember the other guy.

I really enjoyed learning how to escape from a side headlock. For the next thirty years of my life I secretly hoped that someone would have tried to put a side headlock on me. If they were under 250 pounds, they might have been in for a surprise.

I really enjoyed learning how to escape from a side headlock. For the next thirty years of my life I secretly hoped that someone would have tried to put a side headlock on me. If they were under 250 pounds, they might have been in for a surprise.

The most memorable aspect of MP training was bivouac, an overnight camping trip. Each of us was issued a pack and half of a tent. We were paired up with another member of our squad, in my case Dawson Waites. We were also issued M16s and a cartridge full of blanks. Since Dawson was one of the road guards, he was issued an M60 machine gun, which was heavier, instead of a rifle. He also was assigned to the TOC (Tactical Operactions Command). So, we put up our tent together, but he spent the night at the TOC. I had the tent to myself.

A few of the guys were assigned to be the enemy. They were supposed to plan some kind of attack on our campsite. We were told to set up a schedule so that one of the two occupants of the tent was on guard at all times. I, however, did not have a tentmate. So, my choices were to go to sleep, to stay up all night guarding an empty tent, or to do some combination of the two. I chose the first option.

AJ Williams was in the tent next to mine. When he was on guard duty and I was half-asleep, he ran around yelling about how he had spotted the enemy. He set his rifle on my tent about one foot from my head and shot off a round or two. Then he ran around and yelled some more. He put the rifle back near my head and shot off a few more rounds. I pretended that I didn’t hear him and stayed in the tent. I kept up the act the next morning and remarked about how easy it was to sleep in the fresh open air.

On the next day we went to MP City, which was a mock-up of a few blocks of a real city. They taught us riot control. The techniques that we learned bore no resemblance with what you see in 2020. Basically, we just stomped our feet as we walked.

A sergeant taught us the proper way to search someone. To see if we learned the lesson he gave half of us a bunch of pencils and told us to hide some on our bodies. Then another trainee would search us to see if he could find all of them. The guy who searched me was from F Troop. It did not surprise me that he could not find any of the six pencils that I hid in or under my clothes.

We also learned how to direct traffic. The public is supposed to assume that you have a stop sign on your chest and your back. You never face the traffic that you want to proceed. Those cars are on your right and your left.

The written test and the physical test were both pretty easy. No one studied or practiced, and everyone passed.

The last big event that we faced before the graduation ceremony was the commander’s inspection. Our CO, whom I remember not at all, was scheduled to come to the barracks wearing a pair of white gloves. In addition to looking for dirt, he also could quiz anyone on any subject.

We were allowed a few hours to prepare our gear and our brains for the inspection. For the first time ever our sergeant appeared in the barracks. He called us together and told us, “If anyone asks you if anyone checked you out for this inspection, tell them that I did. Has everyone got that?” Then he left to shot a few more racks of pool.

An hour or so later the sergeant came back and walked around the barracks. He eventually came over to me and asked me, “Did anyone check you out for this inspection?”

I quickly responded, “Yes, sergeant.”

“Who checked you out?” he asked.

“You did, sergeant!”

He then examined the name tag on my fatigue shirt and jotted it down in his notebook.

The inspection itself was not very memorable. Jerry White had a skin condition that prevented him from shaving. He used some kind of depilatory cream. In the place in his footlocker reserved for a razor he had placed the knife that he used to remove the cream. The captain may have let him skate on that, but the knife was clearly marked as belonging to the mess hall. Jerry had stolen it. He got yelled at, but nothing came of it. At that point they just wanted to get rid of us.

The next day at roll call the captain announced the names of a dozen or so trainees, including Ned Wilson and me, who had been recommended for promotion. One of the fuck-ups was named Lovado, and when they called my name (mispronouncing it wuh VAH duh), he pretended that they had called his name and danced around in celebration.

We had to face a board of review of sergeants and officers one at a time. They asked us a bunch of questions. I missed one about the name assigned to some kind of flag, but I was the only person who got one of the questions right: “What is the first thing that you do in the event of a chemical, radiological, or biological attack?”

My answer: “Stop breathing.”

So I got promoted to E2. I now was allowed to sew a stripe on my sleeve. It was also worth a few dollars per month, but it ended up being worth more than that to me. I was quite sure that my promotion was all due to the fact that I had lied to the platoon sergeant about my gear being checked out.

Then came the moment of truth in which they announced all the permanent duty assignments. Wainwright got White Sands, NM. Willems, Williams, Wilson, Zimmerman, and I got Sandia Base, NM. So the last five college graduates in alphabetical order all were going to SBNM. This was great news.

Then came the moment of truth in which they announced all the permanent duty assignments. Wainwright got White Sands, NM. Willems, Williams, Wilson, Zimmerman, and I got Sandia Base, NM. So the last five college graduates in alphabetical order all were going to SBNM. This was great news.

We were all ecstatic. I asked one of the sergeants whatt Sandia Base was like. He was astounded that I had been assigned there. He said, “You got Sandia? That’s the best duty in the whole country.

I cannot remember anyone else’s assignment, not even Dawson Waites’. He was not sent overseas, but some people were.

It appeared I and all of my friends had avoided the threat of Vietnam. Now we had to work out some way to tolerate the next twenty months as Army cops.