Getting to and learning about SEAD. Continue reading

My recollections of the period between my departure from SBNM and my arrival at SEAD are very sketchy. Someone on the base in Albuquerque must have helped with the travel arrangements. I am pretty certain that I did not bring my golf clubs, my stereo and speakers, my album collection, and other bulky items to SEAD. So, they must have been shipped to my parents in Leawood, KS. I assume that before I left I was also debriefed, which is the Army’s way of saying that I was warned me not to tell any communists about any of the mission-critical classified information and activities that I saw at SBNM.1

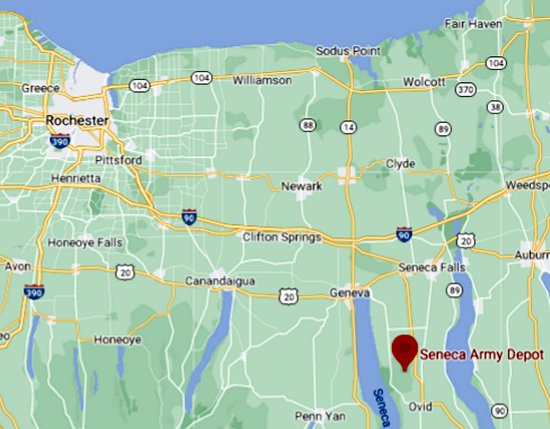

I flew from the Sunport to KC, spent a few days with my family, and then on January 10 I flew to Rochester, NY, which is as close as you can get to SEAD using commercial aircraft. I don’t remember any of that.

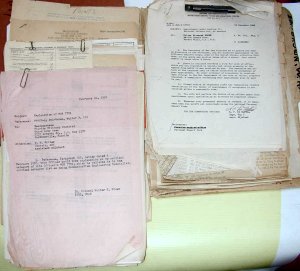

The one thing that I clearly remember is that I was handed my own personnel file (called a 201) and told to hand it over when I arrived at my new post. This amazed me. If they let me do this, it seemed likely that each person who was relocated must have been entrusted with his own 201 file. I immediately looked through mine to find the letter of commendation from the base commander prainsing the heroic acts performed by me and my clipboard during the harrowing Siege of Sandia Base that is described here. I found it. What if there had been a letter of reprimand? I could conceivably have received one for my run-in with Capt. Creedon or my attire at the base EM committee meetings (both described here). Could I have just removed derogatory items at will? I don’t see why not. Computerized records were not yet ubiquitous. Paper still ruled.

The one thing that I clearly remember is that I was handed my own personnel file (called a 201) and told to hand it over when I arrived at my new post. This amazed me. If they let me do this, it seemed likely that each person who was relocated must have been entrusted with his own 201 file. I immediately looked through mine to find the letter of commendation from the base commander prainsing the heroic acts performed by me and my clipboard during the harrowing Siege of Sandia Base that is described here. I found it. What if there had been a letter of reprimand? I could conceivably have received one for my run-in with Capt. Creedon or my attire at the base EM committee meetings (both described here). Could I have just removed derogatory items at will? I don’t see why not. Computerized records were not yet ubiquitous. Paper still ruled.

The instructions on my orders indicated that after my plane landed I should board a bus for Canandaigua, NY. When I arrived at the bus station there, I was still thirty miles or so away from SEAD, which is located near Romulus, a bump in the road between Seneca Lake and Cayuga Lake. I have no clear recollection as to how I made the last leg of the journey. I remember that there was no snow on the ground as we approached the base, but it had started to snow before I exited from the bus, van, car, or truck that brought me. Soon it was coming down hard. Incidentally there was snow on the ground all the way to the day that I left, April 10.

The instructions on my orders indicated that after my plane landed I should board a bus for Canandaigua, NY. When I arrived at the bus station there, I was still thirty miles or so away from SEAD, which is located near Romulus, a bump in the road between Seneca Lake and Cayuga Lake. I have no clear recollection as to how I made the last leg of the journey. I remember that there was no snow on the ground as we approached the base, but it had started to snow before I exited from the bus, van, car, or truck that brought me. Soon it was coming down hard. Incidentally there was snow on the ground all the way to the day that I left, April 10.

You can just drive in now, but the barriers were always down when SEAD was still operational. At least two MPs with rifles manned the main gate.

I remember that the main gate seemed to have a much more serious security detail than at SBNM. The MPs were armed with M16s, and they stopped every vehicle. There were three sets of fences; one was topped by rows of barbed wire and one electrified. At SBNM we ordinarily just waved everyone in.

Someone showed me to my room. The barracks were not nearly as opulent as the ones at SBNM. Every room had two occupants. My roommate was from Texas. I don’t remember his name—in fact, I only remember the name of one person whom I encountered in my three months at SEAD. This failing astounds me. I usually remember names.

He was a little shorter (in height, not less time remaining) than I was, but he was powerfully built. I later learned that he was the high school state champion weightlifter in his weight class. He had a temper, too. I gave him a wide berth.

I asked him if they had regular room inspections. He said that there were inspections, but they were not very common. So, I just piled all my stuff in my locker and locked it. I didn’t make my bed every morning either. My lack of standards for orderliness became a sore point with him. He might have resented the fact that I was so short (in the Army sense), too.

The next morning I was interviewed by a female2 civilian in the MP office. This was something of a surprise to me. SEAD had a lot of civilian employees. SBNM did too, but there they almost all worked for Sandia Labs doing God knows what. Civilians at SEAD were hired for jobs that I would have expected military personnel to do at SBNM.

I handed my personnel folder to the lady who was interviewing me. She was shocked and disgusted when she discovered that I only had eighty-eight days before I ETSed. “April 10! What are we supposed to do with you for less than three months?” I had no answer. They decided to assign me to help with paperwork at the Intelligence Office, which required a walk of a block or two from the barracks. I never worked even one day as an MP at SEAD, but I still stayed in the MP barracks.

The commanding officer of the 295th MP company was Capt. D’Aprix. He gave a security briefing to a handful of newbies. Some might have been civilians. Some might have come from SBNM.

The first sergeant of the company (always called “Top”) may also have been there. If he said anything, it did not impress me enough to stay in my memory.

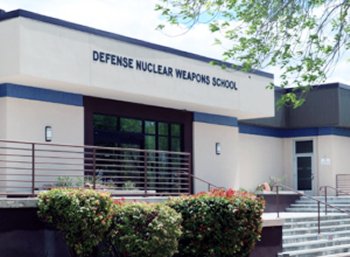

Capt. D’Aprix emphasized that security was everyone’s responsibility at SEAD. A “depot” in military terminology is a place to store something. He said that “special” weapons were stored there. The actual nature of the weapons was—and still is!—highly classified, and we were not allowed to disclose what kind they were. He did not mention it, but the units of the soldiers who worked on SEAD were not classified. All the MPs and all the technicians who maintained the weapons wore patches with mushroom clouds on their sleeves identifying them as belonging to the Defense Nuclear Agency. The technicians all came from SBNM, an open base. The building in which they were trained displayed the words “DEFENSE NUCLEAR WEAPONS SCHOOL” in letters that were more than a foot high. Anyone who could not figure out what kind of weapons were in the depot was too stupid to be dangerous.

We were also told to be on the lookout for card-carrying communists and other shady characters who were interested in what went on at SEAD. It was not feasible for all areas to be guarded all the time. Therefore, the MPs patrolled the entire base (or at least the part within the fences), and the ever-changing routes that they employed were TOP SECRET. So, if we were in a bar or other establishment in one of the neighboring towns, we needed to keep our guard up and our mouths shut.

I was there in the winter. Unless a relative has died, absolutely no one goes to this part of the Finger Lakes in the winter. I guarantee that if any unfamiliar people appeared in Romulus (population about 4,000), they would be noticed by everyone immediately. I suspected as much even on that first day, but I later became certain.

I found the following interesting write-up at https://www.senecawhitedeer.org/index.cfm?Page=Military%20History.

This is a recent satellite image of the entire SEAD complex, which has pretty much gone to SEED since the Army abandoned it in 2000.

In the mid 1950s the north end of the Depot property was transformed into a special weapons area. These special weapons areas (19 in total in the United States) were designated as “Qs”. Becoming a Q area represented the highest security levels known at that time because their mission was to house atomic weapons which indeed were very special weapons.

The Q was built over two years and consisted of about one square mile of area, eventually resulting in 64 igloos, some of them atomic bomb blast resistant. The Q had its own security force, specially trained Military Police who patrolled the Q 24 hours a day. The Q area had a triple wall fence surrounding it, with the middle fence being electrified at 4800 volts. No one was allowed inside the Q without a heavily armed MP escort.

Although the Army still does not acknowledge that storage of atomic weapons occurred within the Seneca Depot, other documents found by SWD suggest that the Seneca Army Depot was the US Army’s largest arsenal of atomic weapons and the second largest atomic stockpile in the entire United States. Besides atomic bombs, the Depot also housed atomic artillery shells for Atomic Annie, a long range artillery gun only fired once in Nevada.

Today, the Q is peaceful once again, this time being leased by Finger Lakes Technologies Group, as it recycles some of the igloos for secure document storage.

I never heard anyone talk about the Q area. I had no idea that there was anything else on the base besides the part that we patrolled.

After the base closed in 2000, a group of locals developed really ambitious plans to make it profitable, but very little came of it. The place is now a veritable wasteland.

1. In point of fact, the only thing that I did or saw that required a clearance was the night that I stood watch on Manzano Base. The irony is that at that time my clearance had not yet arrived. I described this incident here.

2. There were no female MPs in the Army in my day. This was the only part of the first half of the movie Stripes that I found outrageously discordant with my experience. Women were, in fact, allowed to become MPs in 1975, and the movie was made in 1981. So, I guess that inclusion of the MP babes was vaguely plausible. That they were attracted to two middle-aged (Bill Murray was 31 at the time, and Harold Ramis was 37) layabouts is questionable.

However, the entire second half of the film featuring the “Urban Assault Vehicle” was, of course, preposterous.