My short career at Hartford Life. Continue reading

Needless to say, I spent the first half of my first working day at the Hartford1 filling out forms. Then I was told that I would be working in the Group Department. My supervisor for the afternoon was the woman who kept score at basketball games. However, the next day I was reassigned to the twenty-first floor, the home of Life Actuarial, Individual Pensions, and Special Risk Underwriting.

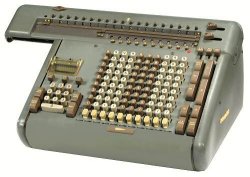

The insurance world had advanced somewhat while I was in the Army. The hordes of clerks with huge Fridens on their desks were still there, but there were a few electronic calculators as well. In 1972 electronic calculators required electricity, and cost as much as the Fridens, about $1,000 each, roughly half the price of my car, Greenie! The companies took strong measures to keep them from being stolen.

My specific assignment was to assist Mike Winterfield,2 an actuary who had joined the Hartford when his old company (in St. Louis, I think), which specialized in variable annuities3, was purchased by ITT and folded into the Hartford. He had a vacation planned, but first he needed to submit a business plan for the VA product to his bosses at the Hartford.

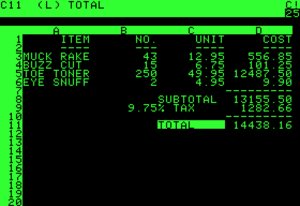

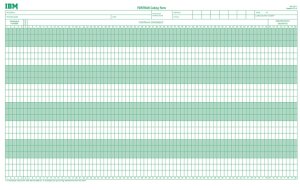

My recollection is that ITT required a return on investment (ROI) of 15 percent for all of its subsidiaries. So, the algorithms that Mike developed for the business plan fixed the return ratio at .15 and juggled the other assumptions to make it work. There were no spreadsheet programs available yet in 1972.4 To evaluate the assumptions Mike designed an accountant’s worksheet with about eleven columns and I don’t know how many rows, probably one for each year. I only helped worked on this for a few weeks; I don’t remember many details. He would change one or two assumptions, I make all through the calculations to determine how much capital infusion the infant product needed to reach the desired rate of return.

Someone else would check my work and put little red dots beside each number that had been verified. This approach, of course, meant that all of the clerical work in the department had to be done twice, but when programs were written to replace the accountant’s sheets, nothing replaced the red dots.

Finally, after many iterations everything seemed to be in order. The plan was submitted, and Mike went on vacation. A day or two later I had the dubious distinction of being quizzed tin a three-way phone call about the plan. The interrogators were Don Sondergeld,5 Vice President and Actuary, and Bob Goode, a high muckety-muck of the Hartford. They asked me several questions that stumped me. I disclosed what I did know, which was limited to how each cell on the worksheet was calculated. I am pretty sure that this information was not what they were looking for. Before I hung up I had to wipe off about a quarter cup of perspiration from the receiver for the telephone, which I shared with Sue Comparetto,6 the only clerk with an electronic calculator.

The only other duty that I remember from my time in the VA area was calculating proposals for salesmen. They told us how much money prospects wanted to invest and when they wanted to receive the annuities. I, of course, had no clue what the market would do in the interim. So, we made an assumption of a specific interest rate, perhaps 6 percent. The sales agents would occasionally call to complain that a competitor’s proposal assumed a higher return that yielded a higher annuity amount or lower premium. I tried to explain that any company could in theory use any interest rate, but the Hartford’s policy was to use the same rate on all proposals. The salesmen often heard the first part, but not the second. They would try to pressure me into giving them a better quote. I never gave in, but once again the phone got drenched with sweat.

For some reason I kept getting moved around. My recollection is that in my first six weeks or so at the Hartford, I sat in five or six different grey steel desks. All of the actuarial students were rotated from one area to another, but nobody moved as much as I did.

My next stop was in the Individual Pensions Department. The name was a little misleading. The purchasers of the product were small businesses, not individuals. For some of the prospective customers it worked out better to buy individual policies for each eligible employee than one group policy.

My first assignment there was to take over maintenance of the program that was used to calculate proposals for the pension plans. An actuary named Fred Smith had been doing this, but the bosses had more important assignments for him. The Hartford offered several varieties of them from single-premium fixed interest to variable annuities. The proposal program could use any interest rate to generate the premiums for a fixed-benefit plan or the benefits for a fixed-cost plan.

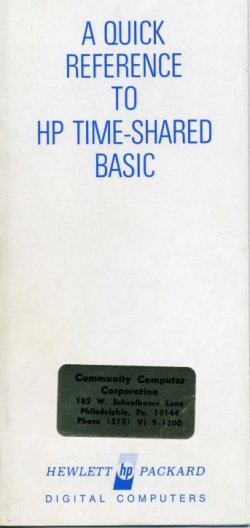

This program ran on a computer that was located not at the Hartford but at Kaman Aerospace. The Hartford had its own computers, of course, but their use was jealously guarded by the Data Processing Department. Many actuaries were quite capable of doing the programming, but it was very difficult to get access to the mainframes. So, the Actuarial Department rented time from two different companies. Kaman had an HP 2000A; Tymshare had a DEC PDP-10. Kaman was cheaper, but Tymshare had more features. We used interpreted BASIC on both systems.

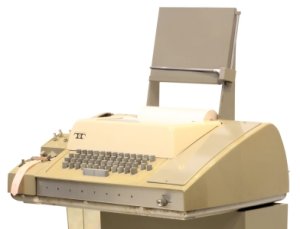

We gained access to the remote systems using a teletype machine connected to a phone line. Our data was stored on paper tape. I think that we stored the programs on the remote hard drive, but I might be mistaken. The teletype had the ability to take information from the keyboard and/or the tape reader. Output was printed on an 8.5″ continuous roll in 10-pitch Courier at a breathtaking ten characters per second. The unit also including a tape-punching device. Because it made a lot of noise when printing or punching, the teletype was isolated in a very small room, maybe 4′ x 8′.

Later a second unit was added. It did not have a tape device, but it printed at thirty characters per second using a round disk. It was not a “daisy wheel”; the disk was metallic and was perpendicular to the page. People came from every floor and from the Hartford’s other building just to watch that baby hum. To many it seemed magical that it could print so quickly and accurately.

The pension proposal program was in good shape when Fred turned it over to me. There was an up-to-date listing, and Fred had inserted a lot of comments. I had to learn BASIC, but a thin handbook of the commands was available. BASIC was similar enough to MAD, the only language that I had ever coded in, that I mastered it fairly quickly.

The first thing that I did was stupid. I removed all the comments to make the program more efficient. In my defense:

- I documented what the program did did on a separate document referencing the line numbers.

- Programs in those days were so slow that removing the comments actually did make it slightly more efficient.

- My one and only programming class was six years earlier, and Господин Muchnik never taught us about documentation.

- I had no training for this job.

- Shut up; I already admitted that it was stupid.

Patti Lewonczyk7 was in charge of producing the proposals. A girl named Paula, who was, I think, fresh out of high school, did most of the data entry. One time something went wrong. I don’t remember what the problem was, but I fixed it easily. However, I had to ask Paula to run the program again for one plan—perhaps a fifteen-minute job. She got very upset and started crying. Evidently she thought that I was yelling at her. I told her that she did nothing wrong, but she was still very distraught.

My second big project in Individual Pensions involved the reports that were sent annually to the companies that had purchased one of these products. A company in New York had developed a software program to produce these reports. A group of clerks led by Carolyn DesRochers filled out coding sheets with the current census information for each plan a month or so before the anniversary. This information was supplied to the Hartford by the customer.

How, you may ask, did we get the coding sheets to the software company? Someone from the Hartford transported a box of them every day to the bus depot downtown. A Greyhound bus then brought them to New York where someone from the vendor picked them up. The vendor’s software program then processed the data and created the report on attractive formatted paper and sent it to Hartford in a box on another bus. Someone from the mailroom picked it up at the bus station and delivered it to Carolyn.

Dave McDonald’s8 title was only Secretary, but that indicated that he was the top man in the department. He summoned me to his office one day to tell me that for some reason the program to produce the annual reports was no longer producing accurate information. The clerks had been observed whiting out the numbers printed on the reports by the computer and inserting corrected numbers using typewriters. This required a great deal of time and produced ugly reports that reflected badly on the company and especially the department.

I Iinterviewed Carolyn and a clerk or two about it. I also talked with someone knowledgeable at the vendor. It turned out that the vendor only allowed for a few choices of interest rate when setting up a policy. This caused no problems for a while, but by 1972 interest rates had started to rise, and the Hartford was quoting (and selling) plans with higher interest rates than the program could handle. The proposal program that Patti’s group ran calculated the interest using standard compound interest formulas. The report program, however, did not calculate interest; it looked it up on tables that someone had populated when the system was written. Evidently the designer of the program did not know the actuarial formulas, and no one had foreseen the significant increases in interest rates. I asked my contact at the vendor if their programmers could fix this. He was not sure that anyone would know how to address it.

I reported back to Dave McDonald all that I had discovered. He was gobsmacked. I never found out what was done about it, and I did not ask who had approved the purchase of a service with such a severe and obvious flaw in it. I designed thousands of programs over the subsequent five decades. I took some wrong turns, but I never made this big of a mistake.

The other task that I remember concerned lapse rates. In determining a reasonable premium for any life insurance product—all the pension plans had an insurance component—it is important to account for the possibility that whoever pays the premium might allow the policy to lapse. In general, there are quite a few lapses in the first year of life insurance policies and much lower rates later. On these policies there were inordinately high lapse rates for the first five or six years. I was asked to examine a sampling of the policies to determine what the causes were.

I discovered that most of the alleged lapses were not caused by the customers’ failure to pay the premiums. Instead, the sales agents were arranging “attained-age conversions”. The agent went to an existing customer and told them that the Hartford was now offering a new product that would be a better deal for them. He would request a quote from Patti for converting the plan. This was done by lapsing the policies on the old plan and issuing new policies based upon the current age of the policyholders. The agent was right. The customer who converted received either lower premiums or higher benefits.

It was a win-win-win-lose situation. The customer and its employees got a better plan, and the agent got a first-year commission on the same plan. Since the first-year commission on many life insurance policies is more than 100% of the first annual premium, this was a real windfall for the agents. Moreover, since the Hartford had four or five individual pension products, an agent could pull the same trick more than once. Quite a few agents had been doing this for years. The Individual Pension products were yielding good sales but no profits.

I know that there were fairly high level meetings that involved Dave, Paul Gewirtz, the actuary in our department, and the Sales Department. The sale people were adamant that this technique should not be taken away from them. Evidently some of the agents who used it were very influential. The problem was not resolved by the time that I left, but in the end my understanding is that the Hartford (and most other companies) stopped selling these products.

At some point someone put me in charge of the computer room and the computers. This did not involve much responsibility, but no one was suspicious if I spent time in there during slack periods. I wrote a program to produce sheets for a football pool. Each week I selected twenty competitive college games and five programs. At the bottom of the page I listed my Bottom Ten college teams. I think that I charged $1 per entry, and the person with the highest score won the whole pot, which was between $20 and $30. I might have gotten in trouble for this, but the spirit of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” prevailed. I won the jackpot once.

On paydays there was also a pool that was run by Wayne Foster. At first employees bought tickets, and the person whose ticket was drawn won the prize. I bought a ticket every week, but I never won. Sue Comparetto won the pool once, and she tried to use the money to buy a round of drinks at the Shoreham Hotel, the site of the customary Friday night get-together of employees from the twenty-first floor. Since she was almost certainly the poorest person in attendance, the offer was rejected and, in fact, roundly disparaged as contrary to the spirit of the payday pool.

After Connecticut instituted a lottery, the rules were changed so that half of the pot was used to buy lottery tickets. The lucky winner got both the remaining cash and the tickets. I never participated in this, and it surprised me that any actuary would have anything to do with lottery tickets, which have a worse payoff than the numbers racket.

At some point Don Sondergeld assigned a special project to Tom Corcoran and me. The company that marketed the software for the APL programming language wanted to sell the Hartford the rights to use the language on the mainframe. The plan was to install in the handful of departments in which actuaries worked expensive APL terminals that were connected to the mainframe. A certain portion of the computer’s disk space would be allocated to the APL users. Something may have been done about sharing memory, too.

The advantage was that the actuaries would gain access to the computing power of the mainframe without being subject to the rules of the Data Processing Department. In those days tying to get new software projects approved and implemented by the DP people was an incredibly time-consuming task. The standard joke was that if you wanted to know how long a project would take, double the estimated amount and use the next higher unit. So, one hour meant two days; six months meant twelve years, etc.

APL programs require far less (in terms of number of characters) of computer code to make the same calculations. However, the APL representatives were unable to give us an example of a project that was relevant to Life Actuarial or Individual Pensions that APL could handle significantly better than Fortran or BASIC. It would be totally inappropriate for the two big projects that I had worked on. Both required extensive use of string variables. In APL a string of characters was treated as an array rather than a different type of simple variable. To me this seemed like a fatal flaw. Tom was more enthusiastic than I was. He liked the simplicity, and he had heard good things about it elsewhere.

I am pretty sure that the Hartford never purchased the product. This project was probably doomed from the start; my specialty was debating on the negative. Selling me on anything is very difficult.

The bills from Kaman and Tymshare produced a strong reaction. The Hartford bought its own HP 3000 computer and charged the Operations Research Department, not the Data Processing Department, with its management. A guy named Gerry Schwartz was put in charge of the new machine. Its operating system supported both BASIC and Fortran. The connections were over telephone lines using teletypes. Users in several departments brought over some simple BASIC programs that they had been using on Kaman’s HP 2000, and things went quite well for a while.

After my stint in Individual Pensions I was rotated to work for Jan Pollnow. My primary responsibility was to produce a monthly report, which my predecessor Chris DesRochers9 (husband of Carolyn), had been generating using a set of columnar accounting sheets.

I decided to write a BASIC program on the HP 3000 to replicate Chris’s sheets. As I added more code it got slower and slower. Eventually it brought the system to its knees. I had to set it off to run when I left at 5:00 and hope that it finished before I arrived fifteen hours later.

Gerry Schwartz blamed this on BASIC. He said that I should convert this new program to Fortran. Since I had never used Fortran, it took a while to do this. The conversion helped a little, but it still was horribly slow. Then Gerry suggested that I use “the segmenter” on the Fortran code. This involved breaking the program into pieces. This was a new concept for me, but at least there was printed documentation. I don’t remember any details of this implementation, but segmenting did improve the performance to a level of barely tolerable.

I spent a great deal of time getting this to work, but it made the monthly task much easier. The program ran without problems for a few months, but then one month’s data produced erroneous results. The problem was easy to fix, but it was a black eye for the department, and Jan called me on the carpet for it. As usual, no one checked my work.10

A few months before my departure Jim Cochran was brought in to our area to work with me. I made sure that he understood both the technical and operational aspects of the program before i started my next adventure.

I retain a few other vivid memories of my days working at the Hartford. People with a “coffee cart” came around every day at about 10 a.m. to sell coffee, donuts, and other pastries. This prompted a coffee break that became longer and longer over the weeks. Eventually the bosses warned everyone not to turn it into a floor party

I cannot remember the exact time that the buzzer rang to indicate that it was closing time. I wager that most of the clerical employees can. A large portion of the clerks, almost all of whom were female, would have all of their materials put away and their belongings gathered well in advance. The mad dash to the elevators when the buzzer sounded was somewhat comical.

Most of the clerks in Life Actuarial were supervised by Bob Riley. Almost all of them had Fridens on their desks, and they used them all day long. The machines were not 100 percent reliable. Every once in a while one would go berserk while performing division and start making awful noises. I am not sure why the clerks themselves were not allowed to unplug the calculators, but Bob always rushed over to take care of it. They generally seemed to work OK after they were plugged back in.

There must be a mountain of those Fridens somewhere. I wonder where it is.

Making copies of documents in those days was a process. At the time photocopiers were both rare and expensive. To my knowledge there was only one in the entire tower. It was manufactured by Xerox, and everyone called it the XM11 machine. Someone would carry the document from the department to the floor on which the machine resided. The courier would stand in line near the operator of the machine. Sheaves of documents were presented one at a time to the operator, who passed judgment on whether they were worthy of duplication. For those that qualified copies were made, and both sets were given to the courier.

It might have been possible to use interoffice mail to do this, but there was no telling when (or even if) the documents would be returned.

I searched the Internet for pictures of photocopiers from this era, but I found nothing that approached the bulk of the one used at the Hartford (as I remember it).

1. I did not realize this at the time, but the Hartford was owned by ITT, which was then the prototypical conglomerate. Under Harold Geneen the company acquired all kinds of businesses. When Geneen left, the ITT spun off the Hartford.

2. In 2023 Mike Winterfield was still an active member of the Hartford Bridge Club. I played with him at a tournament once, as described here.

3. The purchaser of an annuity agrees to pay an amount—all at once or in installments. The party selling the annuity adds interest and deducts expenses and profit before paying it back in installments when the purchaser reaches a certain age. In variable annuities the interest rate is recalculated each year based upon the performance of the stock market or another index. Insurance components complicate the calculations. In the early seventies few actuaries were familiar with this product.

4. VisiCalc was released in 1979, but it only ran on an Apple II. Lotus 123 did not appear until four years later! Excel was introduced in 1987.

5. In 2020 Don Sondergeld is retired, but he is an active member of the Hartford Bridge Club.

6. There is much more information about Sue here and in subsequent entries.

7. Patti and Tom Corcoran married while I was coaching debate in Michigan in the late seventies. They had two children, Brian and Casey. In 2021 they both live in Burlington, VT, with their respective families. Patti died in 2011. My tribute to her can be read here.

8. Dave McDonald retired from the Hartford in 1995 as a Senior Vice President. He died in 2011. His obituary is here.

9. Chris died in 2013. His obituary can be read here.

10. These four words will probably be on my tombstone: Nobody checked his work.

11. XM stood for Xerox machine, but everyone still added another “machine” on the end when talking about it.