A good fit for several agencies. Continue reading

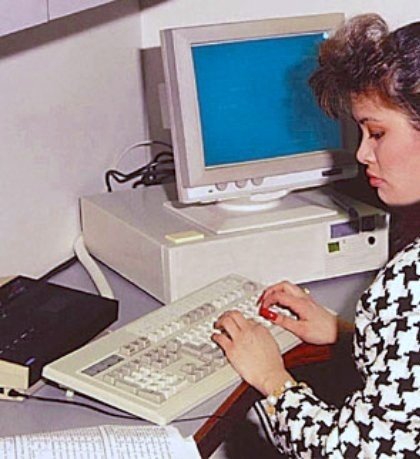

IBM’s Datamaster was widely disparaged in the technical press. PC’s and Macs were the rage. The reasons for this evaluation were persuasive, if a little superficial.

- A Datamaster cost a lot more than a PC.

- The Datamaster’s programs only ran on Datamasters. Many hardware vendors were offering PC’s that were “IBM compatible”.

- The Datamaster could in no way run PC programs.

- The Datamaster’s peripherals—displays, printers, keyboards, and hard drive—were very limited.

- The Datamaster’s specs were inferior. The processor looked very slow.

Nevertheless, the Datamaster was a very good computer for TSI. It was extremely easy to program, and it was very good at the two tasks for which it was designed—data processing and word processing. It was also quite reliable. PC’s crashed all the time. Some of our clients used their Datamaster’s for years without ever making a service call to IBM. Those who did were uniformly satisfied with the attention that they received.

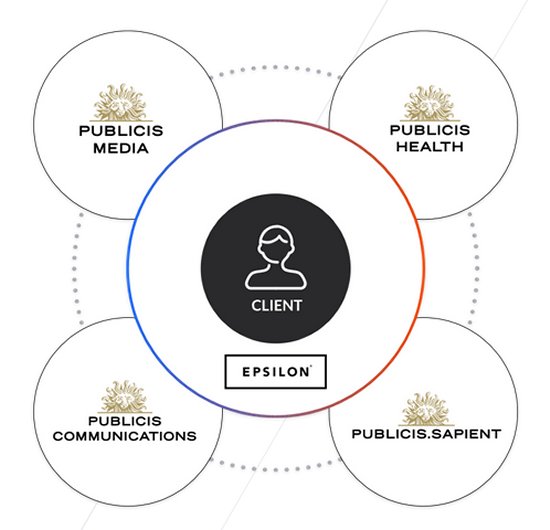

For the ad agency application there was one other overriding advantage. Up to four Datamasters could use the same hard drive. This allowed the media department and the accounting department to have access to the same data. In the early eighties personal computers were totally personal. Reliable networks were many years away.

Yes, the Datamaster was horrible at other tasks such as spreadsheet, and it had absolutely no capacity for graphics. However, most of the people who owned and ran small businesses in the early eighties were interested in addressing business problems. They did not care much about system specs, and the fact that IBM sold and supported the system was of paramount importance to them.

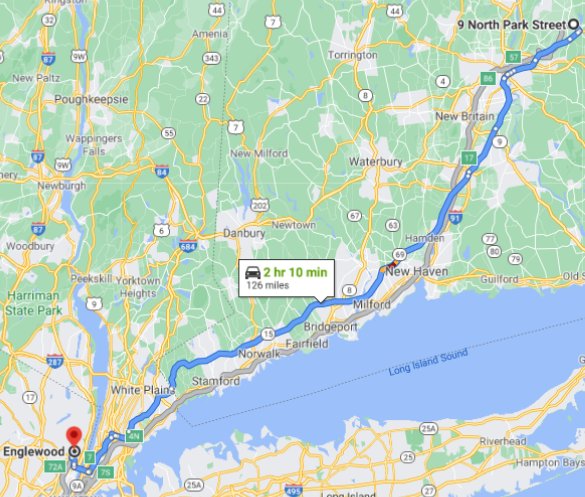

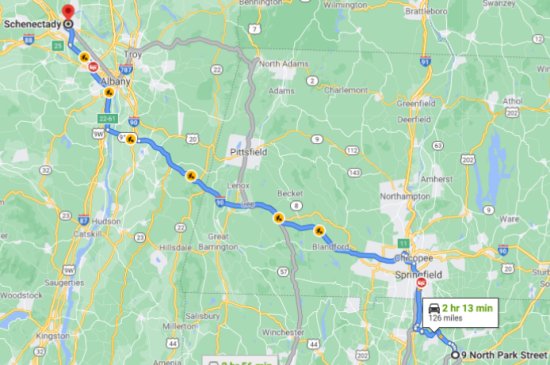

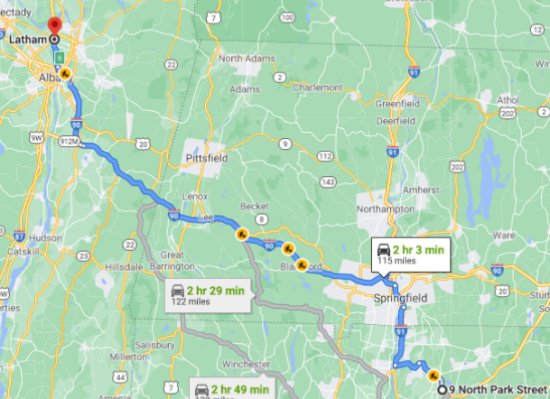

I am almost positive that our third ad agency client was Communication & Design (C&D)1 in Latham, NY, just north of Albany. The principals were Fran (a guy) and Theresa Lipari2. The agency purchased two Datamasters and a hard drive. I am pretty sure that by this time TSI was in IBM’s Business Partner program as a Value-added Remarketer (VAR), and C&D bought the hardware through us. We only needed to make minor adjustments to the software system that we installed at Potter Hazlehurst, Inc. (PHI).

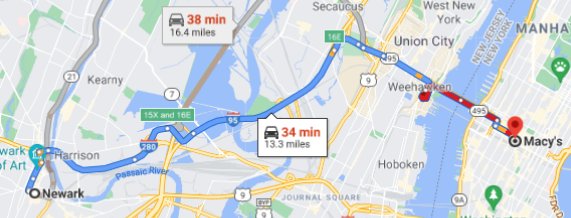

Nevertheless, I made the drive to Albany quite a few times. There was no avoiding personal involvement at several stages in these installations. The transition from manual ledgers to computerized accounting systems was never trivial. The first few monthly closing processes never went completely smoothly.

For several years I worked very closely with the woman most involved with C&D’s system. She was definitely the bookkeeper. She might have also been the office manager. I found her to be intelligent and very easy to work with. I am therefore embarrassed that I cannot remember her name. I recall clearly, however, that she was a big fan of the New York Giants football team. She had even bought vanity license plates for her car that said “NYGIANTS”.

When she left the agency, she was replaced by a woman who was as tall as I was. I don’t remember her name either, but I think that it was French, maybe Bissonet.

I also dealt with the media director when they implemented the media system. I don’t remember her name either, but she was, I am pretty sure, also a principal in the business. She explained to me about inserts3—the advertising pieces that were stuffed into the middle of a newspaper, usually on Sundays and Thursdays. From a database perspective they had pages like direct mail pieces but schedules (lists of newspapers and dates) like newspaper ads. Since we were already using the same set of files for direct mail and newspaper ads, it was not too difficult to set up ad types for inserts.

I remember meeting with Fran after the whole system had been in place for a while. He told me that the media director had started her own agency, and she had taken some of his best clients with her. I never encountered any business that was as “dog-eat-dog” as the ad agency business.

I generally drove up to C&D early in the morning and back at night. I sometimes stopped for supper at a restaurant in East Greenbush. I generally listened to WAMC, the powerful NPR station in Albany. Once I heard—for the first time—the entire recording of The Phantom of the Opera. On another occasion I listened to Lt. Col. Oliver North defending his actions in the Iran-Contra hearing.

A couple of times I stayed overnight. A Howard Johnson’s hotel was right across the street.

Perhaps our easiest installation ever was at The Edward Owen Co. in Canton, CT. The owner was Ken Owen, who was a few years younger than I was. We had (and still have) similar interests. He majored in the classics at Harvard, which prepared him well both to teach Latin and/or Greek somewhere or to take over the family business after he graduated. He chose the road more taken.

The company was named after Ken’s grandfather, who had built the business up to be one of the most successful in the Hartford area. Ken’s father had apparently undone most of that. When we worked with the company Ken had only a part-time assistant and a resident artist who was not on the payroll. His father, who taught Latin at Avon Old Farms school, stopped by occasionally.

It was an easy installation because Ken was the ideal client. He understood and could explain exactly what he wanted. Furthermore, no one else had their fingers in the pie.

Ken and I initiated a lifelong habit of greeting each other on Exelauno Day4 (March 4). Sue and I also went to visit him, his wife Patti, and their two sons a few times. He drove to our house for one of our Murder Mystery parties, too.

Ken was a serious runner. The advertising agencies in New England sponsored a mile run for CEO’s every year. He easily won whenever he entered. I often asked him for advice about running, although what I did he would probably call strolling. I was never close to being in his league.

I don’t remember the name of the artist who worked there, but I vividly recall the nice drawing that he executed for us. It showed three people in choir robes singing from three different hymnbooks labeled “accounting hymns”, “media hymns”, and “production hymns”.

We also asked Ken to help us with the one and only advertisement that we ran. It appeared in one issue of AdWeek New England. That experience is described here.

We created one new module for Yellow Pages advertising. The unique thing about Yellow Page advertising was that the agency only ordered it once. It then ran year after year until someone canceled or revised the ad. Ken’s father said that it was the best kind of advertising. All you had to do was open the envelope every year and endorse the check. Unfortunately, none of our other clients ever had a used for this module.

Ken’s business near Route 44 was next to a strip mall that contained a Marshall’s. We did not have stores like that east of the river. I often popped in there to see if they had anything cheap in my size.

Ken’s company is still in business. He moved the company to Sheffield, MA, which is south of Great Barrington. He also changed the focus of his efforts to, of all things, custom programming. The company’s web page is here.

As you can probably guess, Group 4 Design, which had offices on Route 10 in Avon, CT, was not a full-service advertising agency. They did not place any ads, and, in order to avoid charging sales tax, they were careful not to deliver anything tangible to their clients.

In other ways, however, they were like an ad agency. They billed the time spent by employees, and they could use the job costing and accounting functions designed for ad agencies. So, we treated them as an advertising agency without a media department, an approach that seemed to work well.

I am not sure who the other three members of the “Group” were, but when we worked with them the firm was definitely run by Frank von Holhausen5. Once the system was up and running he seemed satisfied with it. The only thing that I can remember about him is that he was in a dispute with the state because his company had not been charging its clients tax on Group 4’s services. At the time the state had a tax on services6 and the only services exempted from the tax were legal and accounting. Frank complained, “They want to tax my brain!”

I worked almost exclusively with Joan Healey, the bookkeeper. She had difficulty with the first few monthly closings, but after she understood the process, Group 4 was a good reference account for TSI.

Adams, Rickard & Mason (ARM), an ad agency in Glastonbury, CT, used the GrandAd system until it merged with another agency in 1988. I never met any of the principals. In the negotiations and the initial installation we dealt with the head of finance for the agency. His name was Dave Garaventa7.

We met at the house in Rockville. Debbie Priola and Denise Bessette were in the office working. Sue and David and I sat around a table in the office. We were going over some reports that he wanted included in the system. Four of the five people in the room were smoking. After about an hour of this I felt horrible. I excused myself and walked outside to get some air.

At the time of the installation ARM was in the process of moving into offices that someone at the agency had designed specifically for them. Visually, they were quite striking. However, half of the building was on stilts. the area beneath it was used for parking, However, in the winter that half of the building was always cold because it was surrounded by cold air on all sides.

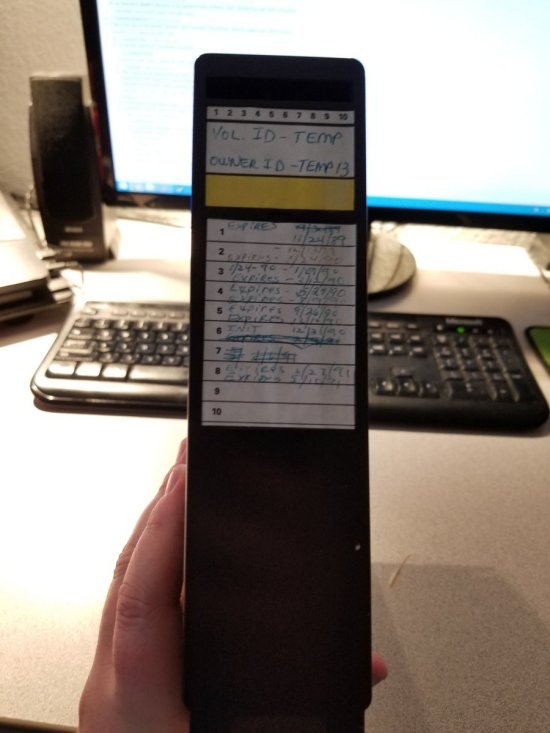

All of the employees were forced asked to take a pencil-and-paper multiple-choice test to determine whether they were “left-brained” or “right-brained”. The results were interpreted as a multi-colored strip that was displayed beneath names on offices and desks. I am not sure why the agency did this. I researched hemispheric specialization pretty thoroughly in college. This was bogus.

Our software maintenance contract with ARM was the same one that we had with every other client. We offered free telephone support during business hours, which were clearly explicated in the contract.

Weekends were sacred to me. I had virtually no time available during the week to program. I spent those days driving around to clients and prospects, training Denise, setting up her work, and writing proposals and documentation. On Saturdays and Sundays I worked on the custom programming that I had promised our clients from before dawn until I got very sleepy in the evening.

On one Sunday morning the phone rang. It was Dot Kurachik (or something like that), the bookkeeper at ARM. I worked with her for almost an hour and solved her problem. I sent her a bill for $75, our minimum charge at the time. She refused to pay. I talked with her boss, and he overruled her.

Cronin and Company of Glastonbury, CT, might be TSI’s only Datamaster client that is still functioning as an ad agency in 2021. Our primary contact was Mike Wheeler, who was, I think, the head of finance. He seemed very level-headed. We did only a little custom work for them.

The main computer operator’s name was Jeannine Bradley8. After using the GrandAd system for several years, Cronin was persuaded to convert to a different software system. We did not get an opportunity to bid on this. We would have proposed a System/36 or an AS/400.

Jeannine called our office about something (I don’t remember what), and she confided to me that they now thought that they had made a mistake when they bought the new system.

I don’t recall any strange or funny stories about this account. The employees always seemed straightforward and competent to me.

The strangest of all of our installations was at Donahue, Inc., an ad agency in Hartford. We did not sell them a Datamaster. They somehow obtained one that had been purchased by Harland-Tine back in the early eighties. The installation at Donahue began in the first months of 1988. It was TSI’s last Datamaster installation.

Donahue’s building did not look like it housed an ad agency or any other business. It looked like an old school, which is close to what it was originally used for. It was the custom-built home of the Cathedral Lyceum9. That designation was clearly etched above the front door.

I don’t remember ever talking to a principal there about what they hoped to accomplish with their system. Their goals, which were explained to me by a woman whom I hardly saw again, were relatively modest. They just wanted to automate their billing and accounting.

The only person whom I dealt with after that was the bookkeeper, a young inexperienced guy. He knew nothing about computers and very little about either bookkeeping or advertising. He and the Datamaster and the printer shared office space with the agency’s kitchen, which was on the ground floor of the building. The first few monthly closings were a nightmare.

Did I mention that there was no heat in the kitchen? The two of us sat there wearing overcoats and stocking caps. The person not operating the Datamaster wore gloves. People wandered in, got a cup of coffee, and quickly retreated to the area of the building that was heated.

The young man who did their books and operated their Datamaster confided to me that his goal in life was to become a real estate agent for Century 21. He really thought that their trademark blazers were cool.

Darby O’Brien Advertising (DOB), a full-service ad agency in downtown Springfield, MA, was not actually a Datamaster client, but I included them is this blog because they used the version of the software designed for the Datamaster. Darby10 insisted on using a Wang PC sold by one of his clients, a store that sold and repaired computers. We grumbled about this plan, but supporting their system this way turned out not to be too difficult for us.

They needed to purchase a license to use Work Station Basic11, a DOS-based product that supported all of the syntax used by the Datamaster’s version of BASIC. We also charged them for converting our code to a format that the Wang12 PC could use, but that took less than a day. In the end they probably paid more for a demonstrably inferior product. Unlike the Datamaster, a Wang PC could run other applications such as Lotus 123, but to my knowledge it was never used for that purpose.

When we installed the system, the accounting person was Caroline Harrington. For some reason Caroline resigned her position at DOB and came to work for us. Sue must have arranged this. I certainly did not recruit her.

The agency’s building was in a rough part of town. It was less than a block away from the stripper bars. I was still relatively bullet-proof then, but I did not like to be there after dark. We did go there at night once, and we had a great time. The agency threw a party, and they invited all of their clients and vendors.

A very good live band played oldies from the fifties and sixties. The highlight of the evening was when they played the Isley Brothers’ hit, “Shout!” Everybody (except for me and my monkey) knew when to get down low, when to raise up, and when to shout. I hate rituals, but this one sort of made me wish that I had gone to at least one mixer.

The restrooms in the DOB offices were easy to find. The door to the men’s room was decorated with a three-foot high picture of Elvis Presley. The ladies’ room had a similarly sized portrait of Marilyn Monroe.

1. The ampersand was important. It was emphasized strongly in the agency’s logo.

2 .The Liparis’ last name was pronounced Lih PAIR ee, unlike the island just off the coast of Sicily, which is pronounced LEE pah ree with a trilled r. I am pretty sure that Fran and Theresa reside in Plymouth, MA, in 2021.

3. I later toyed with the idea of using inserts as the basis of a new business for TSI. Details are here.

4. Ken told me that “Exelauno!” is the Greek word for “March forth!” Google translate does not agree. I sold my ancient Greek dictionary at the end of my senior year. So, I can’t look it up. The origin of this custom is documented here.

5. Frank von Holhausen is now listed as the founder and Chief Design Officer at Forge Design & Engineering of Oxford, CT. His LinkedIn page is here.

6. Frank’s lament and the difficulty that TSI confronted in determining how much of what we did was service and how much was product acted as a key plot element in the short story that I wrote in 1988. The details are here.

7. Dave Garaventa died a year or so after we installed the system.

8. In 2021 Jeannine Bradley lives in Cromwell. She might still work at Cronin. She was promoted to accounting manager in 2012.

9. The Lyceum was built in 1895. You can read about it here.

10. Darby’s agency is still in business, but it has changed locations a few times. The latest headquarters is in South Hadley. He tells his own story here. I can’t believe he let them photograph him wearing a Yankees hat in Massachusetts.

11. Workstation Basic is described in some detail here.

12. Wang filed for bankruptcy protection in 1996.