An unimpressive beginning. Continue reading

In retrospect it seems that it should be rather easy to pin down the date—or at least the year—that our company, TSI Tailored Systems, was founded. The fact is that it was not that big a deal at the time. Sue was already helping to support the software that Gene Brown and Henry Roundfield had installed at their customer’s sites when they proposed that she take on support of the customers as an entity separate from them.

The transition was a simple one. Sue merely had to get a DBA (“doing business as”) from the state of Michigan, which anyone can do. There were no out-of-pocket expenses. Gene and Henry allowed her to use space in theor office in Highland Park. Of course, they were no longer paying her a salary. She needed to make arrangements to get paid by the users of the systems that Gene and Henry had sold. The customers were already paying hardware and software maintenance to IBM or, if the system was new, they soon would be.

One thing that I don’t recall is what was done about phone bills. In those days long-distance calls were expensive, and at least two of the 5110 clients were not local calls. Furthermore, Sue can be gabby on the telephone. I wonder what the arrangements were for those charges.

To tell the truth, I don’t even remember talking with Sue about whether TSI was a good idea. We certainly didn’t draw up a business plan or anything like that. I suspect that she just decided to do it.

The name was definitely Sue’s invention. “Tailored” was the key word. From the very beginning the company’s philosophy was to make the system do exactly what the customer wanted. At first the original code was written by another company (IBM or AIS). After the first few years we wrote and marketed only code that we had written—every single bite of it. The concept of “open source” was not prevalent and definitely not profitable. Even if other developers had offered their code for free, we would not have trusted it. There was a lot of garbage code out there. Some of ours probably was, too, but everyone is used to disposing of their own garbage.

And what did the I in TSI stand for? Fifteen years later it stood for incorporated. Now it stood for nothing, but It was blue with stripes just like IBM’s log.

When did the blessed event happen? Well, all of Gene and Henry’s clients had IBM 5110’s. The 5120, which totally replaced the 5110, was announced in February of 19801. So, TSI must have been started before that. I think that Sue probably made the decision in the last quarter of 1979.

I definitely know what the company’s first asset was. Sue purchased a used steel credenza and somehow got it to the office in Highland Park and from there to our house on Chelsea.

While she was still working in Highland Park Sue communicated with most or all of Gene and Henry’s customers. She told those who were using the AIS software without a license that they needed to obtain a license. I don’t know if Gene and Henry charged them or not. If so, hey must have been furious. In any case, Sue offered them a way out of a potential mess, and most agreed to the offer.

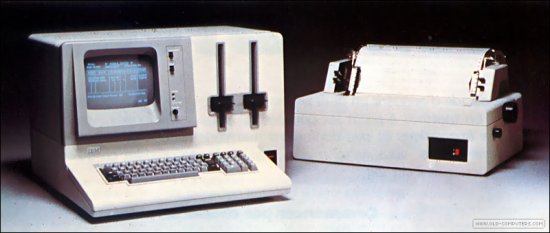

The next major event for TSI was the sudden appearance in our house in Detroit of a 5120. Somehow Sue’s dad, Art Slanetz, arranged for this. Sue told me that some guy named Smith went in on the original purchase, but he later decided not to use it. I had no role in this deal.

We must have received one of the very first 5120’s that were installed in Detroit. I remember that we had a very difficult time to get it to work. The customer engineer (IBM-speak for hardware repairman) had spread out computer parts all over the spare bedroom, which was now the TSI office. He was in there talking on the phone with someone from IBM for several hours. It was nearly 5:00 before he got the computer to work.

Sue used the 5120 to make some necessary changes to the customers’ software. She could then send or bring the updated diskettes to the customers. This was not a great system, but it was better than any feasible alternative. I was never involved with this end of the business. I think that I accompanied her once to Brown Insulation, but that was the extent of it. In fact, the only other reasonably local account was Cook Enterprises, which was based in Howell, MI.

At one point we flew to Kansas City so that Sue could meet with the people from AIS. They were very happy that the customers who had been using pirated versions of their software had actually purchased licenses. They provided her with file layouts and other documentation of their accounting software. Of course we also stopped in to see my parents. We only stayed a couple of days.

Computers were not used for word processing in 1980. My first project was to write and test Amanuensis, a program to store and produce my prospectus and the article that I wrote with proper spacing for footnotes. It did not have a spell-checker. In fact, it lacked a lot of things. Nevertheless, it saved me a lot of time. As far as I know it was the only word processing program ever written for the 5120.

As is described here, I also used Amanuensis to produce big documents for the Benoits. We actually sold a copy of this program to Brown Insulation. It was the first sale of a system that contained only code that we had written. I don’t remember what we charged. I don’t even know if they ever used it. They paid the bill and did not complain about it.

Over the summer of 1980 I wrote the software that is described here for our Dungeons and Dragons adventures. I also wrote a program to keep track of the status of warships in the Avalon Hill game called Wooden Ships and Iron Men. The latter program was never actually used. I could never find anyone to play with.

After we moved back to Connecticut we somehow got a chance to develop an inventory system for Diamond Showcase, a jewelry store with a handful of locations in the Hartford area. I think that the home office was in Farmington.

The company already had a 5120. Perhaps they purchased it to use for an accounting application. The proprietor wanted to use the computer as a multi-location inventory and sales analysis system. He hired someone who ran a small software company (I don’t remember his name) to find people who could do the job. The software guy interviewed some workers at DS put together a half-assed set of specifications. Somehow he heard about us. Maybe it was from IBM, but we did not yet have a close relationship with the Hartford branch.

Sue and I met with the lady at DS who was in charge of the project once or twice. We proposed to do the project for $5,000. Evidently no one else was interested, and so we got it. At that point we might have had business cards and stationery. I wrote up a contract based on one that AIS used.

The more that I think about it the more amazing this seems to me. In the next thirty-five years TSI would be involved in many situations in which we tried to convince people that we possessed the skill and the knowledge to provide what they wanted. Sometimes we succeeded and sometimes we didn’t. I can think of no other occasion on which we succeeded with such sparse credentials. We had no references and no training. Sue’s experience was not close to applicable. I had written some cool programs, but I could hardly show them output from my D&D system. In early 1981 we barely even had a business.

Maybe nobody in 1981 had credentials. Software for small businesses barely existed; we were among the pioneers. Perhaps the software guy vouched for us or at least told them that we were the best people available. At any rate, they signed the contract and gave us a deposit. I went to work.

I wrote all the software for Diamond Showcase using principles that I had internalized reading through the listings for the IBM and AIS programs that Sue supported. The key was to use three diskettes (one for programs, one for detail of transactions, and one for all the other tables) and to process transactions in batches. Although I did not know that I was doing so, I normalized3 all the files.

The system actually worked fairly well considering how little experience that I had. The difficult question in supporting any inventory system is “Why does they system say that I have x of them when there are only y in the store?” This was less of an issue with jewelry. Most of the items are unique, and so the quantity on hand is always 1 or 0. The biggest challenge for a retail jewelry system was to make sure that the user does not run out of room on the diskettes. They only held one megabyte of information, a small fraction of what is used to store a single photo on a cellphone. In 2021 storage on hard drives is given in terabytes. A terabyte is a million megabytes!

TSI’s first installation should have been a momentous event, but I have very few vivid memories of it. I remember that on one of my trips to the company’s headquarters the lady with whom I worked asked me a question that I could not readily answer. She said that she liked the computer and she liked the software. She wanted to know what other printers were available for the 5120. I told her that I was sure that IBM must have other printers. I was wrong. I had to call back to tell her that the one she had was the only one available. I was beginning to learn a little about how IBM did business.

On Monday, March 30, 1981, Sue and I had just driven the Duster into the parking lot of the DS headquarters (not a store) when we heard on the radio that President Reagan had been shot.

Later, of course, John Hinckley Jr’s2 motive for the attempted assassination—to impress Jodie Foster—was disclosed to the public. For a short period it appeared that America might be upset enough about this outrage to try to prevent a similar incident, but we settled for the usual thoughts and prayers.

1. The strengths and limitations of these systems are described here. There was no way to communicate with them from a remote location.

2. Hinckley was found not guilty by reason of insanity. In 2016 he was released from a mental hospital to live with his mother. That stipulation was removed in October 2020.

3. A Wikipedia page explains normalizing of databases. You can read it here. The principles apply equally well to relational databases and those using the indexed-sequential access method (ISAM) championed in the eighties by IBM because of better performance.