The I in TSI comes to stand for Incorporated. Continue reading

This entry requires quite a bit of background.

When we were still living in Detroit, Sue Comparetto founded TSI Tailored Systems as sole proprietor. I helped her occasionally in the early days, but for the most part she did it alone. She never had any employees or, as far as I know, a business plan. She inherited a handful of accounts from her former employer. At first she had an office in Highland Park, a small and dangerous city surrounded by Detroit. Then, when TSI somehow obtained an IBM 5120 computer, she set up shop in the spare room in our house in Detroit.

Having the computer in Detroit allowed me to learn BASIC. Having access to the programs and listings from AIS, the company that wrote most of the software that Sue supported, allowed me to learn how business programs could be structured. We were self-taught. I had taken exactly one college-level programming class at Michigan in 19661; Sue had none. Neither of us had ever taken an accounting or marketing class. In fact, neither of us had ever even sold or helped market anything.

When we moved back to Connecticut, Sue registered TSI as a partnership. We worked together, but we never really agreed on who was responsible for what. I considered myself much better at programming than Sue was. I therefore expected to do the bulk of the coding (including software for TSI to use) and for her to handle nearly everything else. The way I thought of this was: she does the phone stuff; I do the computer stuff.

The first additional task that I felt obliged to take over was marketing. In Detroit Sue had never needed to find new clients. She was given a bunch of them, and she hoped that IBM would provide her with additional leads. When we moved back to Connecticut, however, we lost the ties with the Detroit IBM office, and it was difficult to make new arrangements. We had only a few clients and lousy credentials.

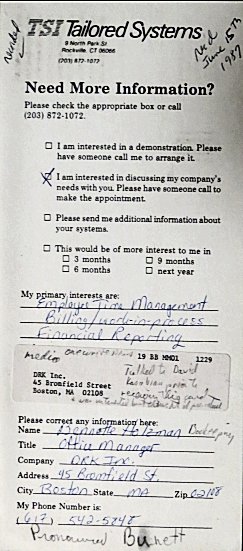

We scrambled to get a few custom programming jobs. I did nearly all the design, coding, implementation, and training. I pulled together a mailing list from phone books at the library and wrote letters to businesses that I thought might be interested in systems designed for our clients. We never made a lot of money this way, but it did generate some business. Eventually, IBM also gave us some leads.

We hired a receptionist/bookkeeper, Debbie Priola, and a programmer, Denise Bessette. The former freed up time for Sue almost immediately. The latter consumed quite a bit of my time for a couple of months, but eventually she helped a lot. Unfortunately, she decided to return to college and cut back on her hours at TSI. More details about the early years of TSI can be read here.

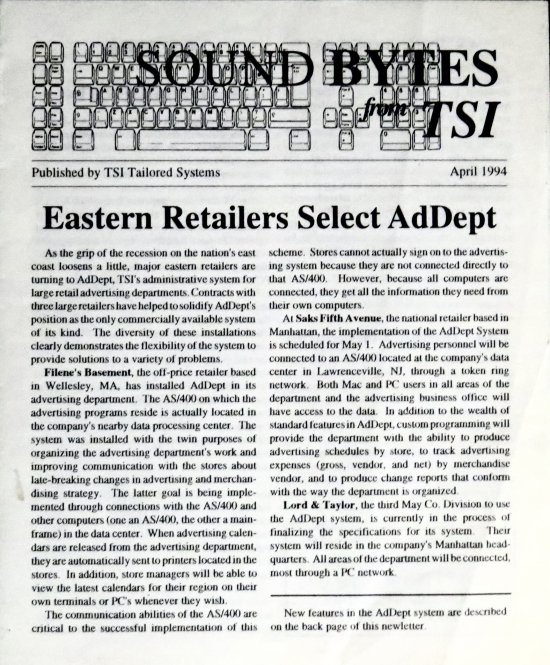

Both Sue and I found most of the decade of the eighties to be enjoyable but frustrating. The programming was fun and very challenging. Almost all of TSI’s customers appreciated our approach. However, we never came up with a good way of monetizing our efforts. The ad agency system, GrandAd, did better than the “anything for a buck” approach that we had been forced to use in the beginning. However, our market was effectively limited to agencies that were within driving distance and were too large for a PC system. In that reduced market, it was difficult to make enough sales to get by. Eventually there were so few reasonable prospects remaining that a change in strategy was essential.

I was convinced that our future lay in selling AdDept to large retail advertisers across the country. There was no real competition, and there seemed to be a good number of prospects.

I don’t think that Sue agreed with this change in focus. She had always favored local businesses over large corporations when purchasing something, and I am pretty sure that she also preferred dealing with smaller businesses over dealing with corporate executives. The fact that both of our first two AdDept clients declared bankruptcy and left us with tens of thousands of dollars of noncollectable invoices reinforced her attitude.

Sue had always been a night person. I was the opposite. I always was out of bed by 5AM or earlier. I usually became very sleepy around 9:30PM. I then took a shower and read a few pages of a book in bed. I was almost always asleep within a minute or two of turning off the lights. I stuck to this routine for decades, and I still do in 2021.

At some point in the eighties Sue developed a sleeping problem. She liked to watch late-night television, but she almost always dozed off in her chair. She slept very fitfully, waking up with a start and then falling back asleep. This went on for a long time—months, maybe years. Finally she went to a doctor. He prescribed a sleep study. It was not a surprise that it confirmed that she had sleep apnea. For reasons that I have never understood Sue was reluctant to purchase and then use the sleep machine. The models sold in those days were big, expensive, and ungainly. Even so, breathing well while sleeping is critical to good health.

I suspect strongly that this long period in which she was not getting enough oxygen when she slept impaired her performance at work and elsewhere. She regularly came in to the office late—very late. She was late for appointments. She missed appointments all together. The books were never closed on time. She repeatedly put off providing the accountant with tax information, even though the company’s operation was not a bit complicated. There were many other issues, but the worst thing, from my perspective, was that she made employees call the people with whom she had appointments in order to make excuses for her.

In 1987 or 1988 Sue gave up smoking. At almost exactly the same time, Denise did, too. So did Patti Corcoran, Sue’s best friend, and, halfway across the country, my dad. This was like a dream come true for me. I had never taken a puff, but for years I had worked in smoky offices and had taken Excedrin for headaches. When TSI’s office was declared smoke-free, my headaches went away forthwith, and they never returned.

Sue, in contrast, had a very difficult time quitting. She put on quite a bit of weight, which amplified the sleep apnea problem. She was also more irritable at work and at home.

I must mention one other factor: Sue never throws anything away. Okay, if it has mold on it, or it is starting to stink, she will discard it. Otherwise she stuffs things for which she has no immediate use in bags or boxes.

When I first met Sue, she was renting one room in the basement of someone’s house. It was not cluttered at all. She seemed to have no possessions except a water bed, a record player, and a few albums. By the early nineties we had a house of our own with two rooms that had no assigned function, a garage, an attic, and a full basement. All of them soon became full of junk. Both of our cars had to park outside because the garage was wall-to-wall miscellany.

TSI’s headquarters in Enfield was nearly as bad. Sue’s very large office was the worst. Strewn about were boxes and paper sacks full of correspondence and memorabilia. Her desk was always completely covered, and post-it notes were everywhere.

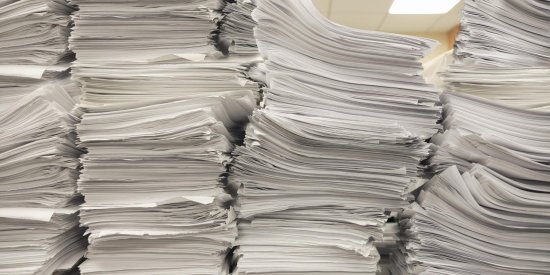

In the rest of the office stood several file cabinets. Of course, every business must retain records, and one never knew when the company might get audited. It was also critically important to maintain good records about contacts with clients and prospects, and our business, in particular, needed up-to-date listings of programs, which we had by the thousands. So, we had a lot of important paperwork.

However, in TSI’s office could be found many other things, which by any measure were totally useless. One day I undertook to throw away the announcements that we constantly received from IBM about its products. These documents formed a stack about four feet high. 90 percent of these missives were about mainframe products. There was absolutely no chance that we would ever work with any of these machines. Even the remaining ones (all of which I intended to keep) were seldom of any value because the information might have been contradicted by a subsequent notice.

Sue asked me what I was doing, and I told her. She immediately got very upset and even started to cry. She just could not stand for anyone to make the decision to discard anything that she considered hers. I realized at that moment this was a reflection of a very serious problem. I put all the notices back in the file cabinet.2

1994: It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.

The business was finally taking off. Our new salesman, Doug Pease, was demonstrating that he was ideal for the job. The nationwide retail recession had ended. The retail conglomerates with money (or credit) were gobbling up smaller chains, and in most cases this worked to our advantage. We were approaching a position in which we need not ever worry about competition. Most of us were working very hard, but we were getting new clients, and it was exciting.

The problem was Sue. She was hardly involved in any of this at all. Her behavior was becoming really unprofessional. Doug complained about her often. She kept hiring assistants, and they kept quitting. I could not find out where we stood financially because our books were so out of date.

On a couple of occasions I was stretched so thin that I asked Sue to take trips to clients for me. I did not think that technical expertise would be involved. I just needed someone to find out what the users needed. The first one was to Macy’s East in New York. Sue never told me what happened, but the people at Macy’s told me years later that they had made voodoo dolls representing her and stuck pins in them.

The other trip was to Foley’s in Houston. Sue flew all the way there and then realized that she had brought no cash. Her credit cards had all been canceled by the issuers. Fortunately, she had a checkbook, and Beverly Ingraham, the Advertising Director at Foley’s, cashed a check for her.

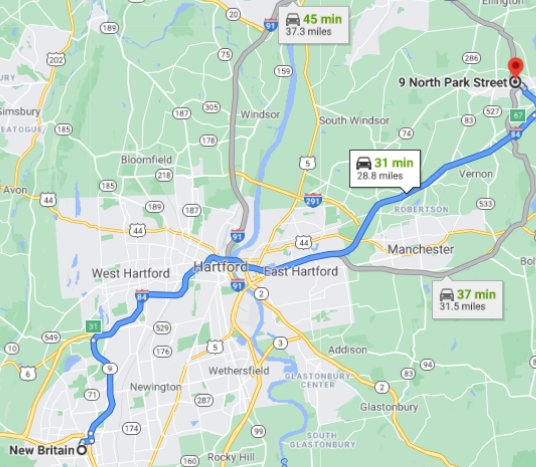

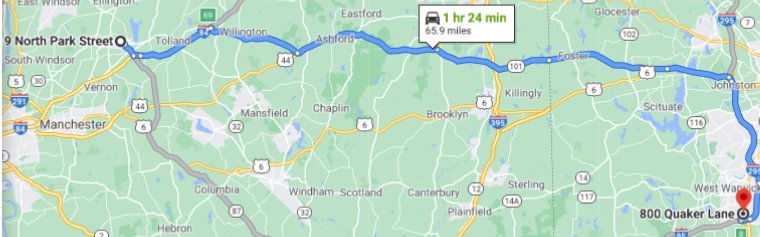

In May of 1994 Sue and I took a very important road trip to Pittsburgh. We met with Blattner/Brunner, an ad agency (described here), and Kaufmann’s, a chain of department stores (described here). Both of these sessions went quite well. When we returned to Enfield, I was required to spend a lot of time working on the proposal for Kaufmann’s. It was the most complicated and difficult one that I had ever done, and if I did not do a good job of analyzing and estimating the difficulty of each element, we could suffer for this for years.

So, I asked Sue to follow up on Blattner/Brunner while I was working on Kaufmann’s. Sue had been there for the session in Pittsburgh. There was no one else I could turn to. She completely fumbled the ball. I was quite angry, but I knew that it would do no good to nag her about it.

On the other hand, I appreciated the fact that she was the founder of the company. These opportunities never would have happened if she had not started the ball rolling back in Detroit.

The day finally came when I just could not take it any more. I told her to go home and not to come in to work any more. There was no argument and no tears. She told me that I was making a big mistake and just left.

No one else thought that it was a mistake.

Within a day or so I approached Sue with the following arrangement: TSI Tailored Systems Inc. would be registered as a Chapter C corporation.

I would be president and have 55 percent of the stock, and Sue would would be treasurer with 45 percent. We would hire a new accountant to handle the corporation, and the bookkeeper would report to me. It would be my responsibility to make sure that the books were closed on time, and the taxes were paid on time. I would also do our personal taxes. We would fund the corporation with the difference between our accounts receivable and our accounts payable. If it needed cash (as it did a few times), I would loan as much as necessary to the corporation at a reasonable interest rate.

Sue was not happy about it, but she agreed to this. She did not even argue about the salary amounts that I set.

Our new accountant’s name was Sal Rossitto2. He guided us through the transition. He advised us to set up an Limited Liability Company3, but I insisted on a true corporate entity that issued stock to its owners.

Setting up the new corporation was fairly straightforward. We had to open a new bank account. I found it to be a fairly simple matter to close the books every month within a day or two of the end of the month. We also set up a 401K with matching funds, a profit-sharing plan, and a good health and disability insurance plan from Anthem. None of this was difficult.

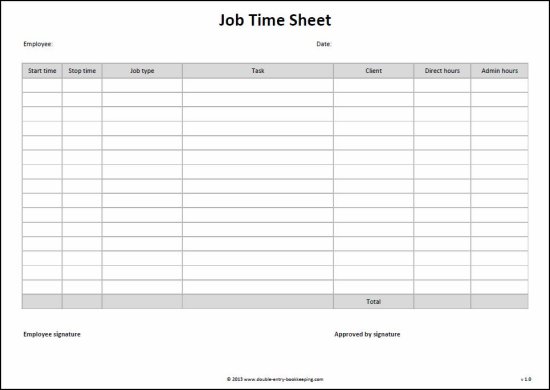

I am not sure who took over handling of the payroll after Sue left. TSI eventually hired Paychex to do it. Denise collected the time cards from the employees and submitted the requisite forms to Paychex.

I made one very good decision. We set our fiscal year to run from December 1 through November 30. We paid bonuses and made contributions in November. This gave all the employees the entire month of December to spend or save for tax purposes.

Dissolving TSI was a much more complicated task. Sue and Sal met often over the course of several months to unravel issues in the partnership’s books. I remember, among other things, some kind of ugly situation with regard to sales tax in California regarding the way that the installation at Gottschalks occurred. At the end of this process Sal confided to me that he now understood why I wanted to set up a real corporation.

We also ordered new letterhead. Ken Owen worked with me on the logo. I eliminated the stripes and the lean of TSI. The color around the TSI was pure blue. The colors to the left of that block went from a very light blue gradually darker almost to pure blue. The effect worked better on the computer screen than it did when printed.

For me the most important thing was to reestablish blue as the company’s color. It started with a light blue as shown at the top of the page, but over the years it had somehow evolved into something that was more green than blue. I hated it.

The next few years were boom years for TSI. I worked my tail off, and my travel schedule was a killer. I didn’t care. We had finally turned the corner, and the future looked very bright.

Life at home, however, was very difficult. Sue was obviously unhappy. She probably thought that I intended to dump her. I still loved her; I just did not want to work with her any more. I was quite sure that the company would do better without her.

displayed no interest in finding a job. This surprised me. She had had quite a few jobs since I met her. She really liked a few of them. She could summon up a great deal of enthusiasm about new projects, and she loved meeting new people. I could think of several occupations that she would fit very well.

Instead, she leased some space in an old office building in a questionable part of downtown Springfield, MA. She then fixed it up and rented it out to dance teachers who needed a place to give lessons. I don’t know how much of our money she lost on this venture. I am not sure that she even kept records of it. She certainly didn’t ask my opinion about it.

On weekends we still drove to Wethersfield to visit our old friends, the Corcorans, regularly. That helped quite a bit.

At one point Sue awarded herself a vacation. She drove to New Orleans to see a guy that she knew from high school who was into social dancing. She stopped at some other places along the way. I never asked her about what happened on this trip. When she returned she did not offer any details.

Eventually things got a little better. After the trip to Hawaii (described here) in December 1995 the situation became more tolerable for both of. At least we had some money to spend and save for the first time ever in our relationship.

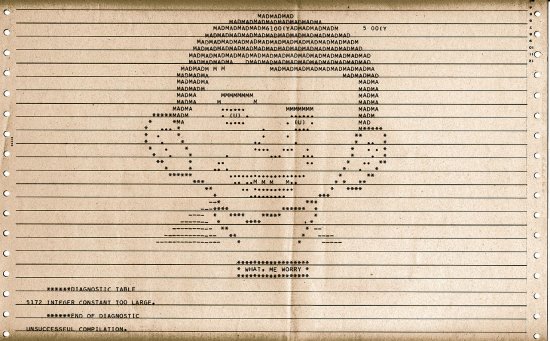

1. The course that I took as a freshman at U-M taught a programming language that was unknown outside of Ann Arbor. It was called MAD, which stood for Michigan Algorithm Decoder. We wrote our programs on 80-column punch cards.

2. Perhaps you are wondering why I gave in without an argument. It was because I recognized quite early in our relationship that Sue was expert at playing the “Why don’t you …? Yes, but …” game described by Eric Berne in his best-selling book Games People Play. A pretty good write-up of the “game” is posted here. This is also the reason that I did not press her about the sleep apnea.

2. Sal Rossitto died in 2002. His obituary is here.

3. The purpose of an LLC is to protect the “members” from being personally responsible for debts and obligations undertaken by the company, but it is not as completely separated as a true corporation.