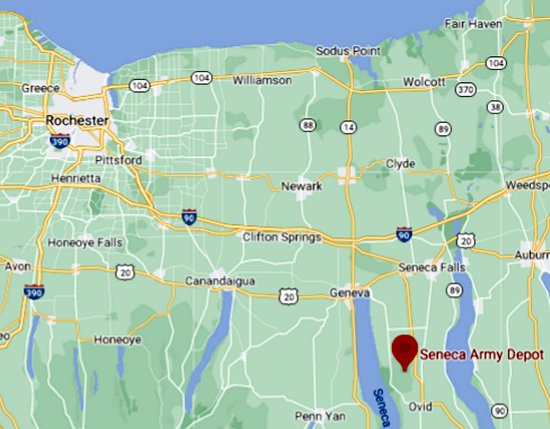

Working at SEAD. Continue reading

I worked in the Intelligence Office at SEAD for a little less than three months. I worked with the same five people for almost that entire time. I find it puzzling and a little irksome that in 2020 I can remember none of my co-workers’ names, and I also can recall very little that I personally did there.

I attribute this failure to three things.

- Almost nothing even slightly memorable—especially compared to SBNM—happened in those three months. There were no incidents whatever.

- My work was totally routine. I remember nothing but typing and routine filing.

- I had a bad attitude. My thoughts kept gravitating toward my ETS day.

Here are the four people who were already working in the Intelligence Office when I arrived:

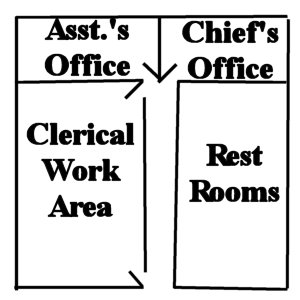

- The Chief Intelligence Officer (CIO) was a civilian. I had almost no dealings with him. I have only a vague idea of what he did. I had no idea whether he worked for the CIA, the DIA, or some other acronym. He had a private office and lived off-base.

- The Assistant Intelligence Officer (AIO) was an Army lieutenant. He was not a lifer. I worked with him a little and even socialized with him once. Nevertheless, I would not hazard a guess as to his job description. He also had an office and lived off-base.

- The chief clerk as a middle-aged woman who had worked with the CIO for several years. I thought of her as my boss. She with us at her desk in a rather large area with three desks surrounded by shelves and filing cabinets, but no walls or dividers. She lived off-base.

- A PFC had been working in the same area as a clerk-typist for a few months when I arrived. I am not sure whether he was classified as an MP or a clerk-typist, but he lived in the barracks. He and I got along very well, and we socialized together a little. I was a SP4, and so I outranked him, but even at the end of my time at SEAD he knew the job better than I did. So, if he said something needed to be done, I did not question it.

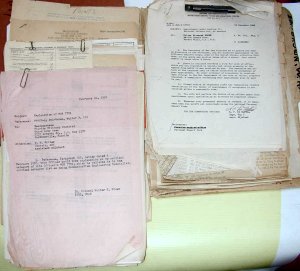

When I arrived at the Intelligence Office there was a backlog of paperwork. The quantity of reports, letters, and what-not was a little more than the two people in the big work area could easily handle. On the other hand, there was not enough work for three people. After I was there for a couple of weeks, the backlog had disappeared, and my PFC friend and I had plenty of spare time.

Towards the end of January the three of us in the big work area were joined by another soldier, a sergeant who was TDY1, which meant that his was a temporary assignment. He did not know how to type, and so we had very little work for him. We also did not have a desk for him. So, he just sat on a chair in our workspace and twiddled his thumbs. I would have found his situation very stressful. My brain needs to be occupied. When I try to relax my thinking, I generally fall asleep. In my first summer job I had little to do, but I was required to look busy. It was a difficult situation for me. The link for the blog describing that summer will be linked here.

I think that the sergeant on TDY was still there when I ETSed in April. I never did find out what his next assignment was.

The soldiers in the office wore the winter version of the “Class A” uniform. This consisted of:

- A dark green suit coat that had space for all of the badges, insignias, and medals.

- A light tan long-sleeve dress shirt.

- A plain black tie.

- Trousers that were, I think, the same color as the coat.

- Black dress socks.

- Plain black shoes, which were not ideal for walking through the snow that was on the ground from the day that I arrived until the day that I left.

- An olive drab “garrison” or “envelope” cap. This was the most practical headgear. In 1972 soldiers ALWAYS wore headgear outdoors and NEVER wore headgear inside. The garrison cap could be folded once and kept on the belt when indoors.

- We also had a government-issue overcoat and raincoat. I never used the latter.

I am pretty sure that we hung up the coats somewhere as soon as we got to the office. I only had one suit coat, and I worked Monday-Friday. I don’t remember how we managed to have clean uniforms every day, but I cannot remember any problems. There must have been really good laundry service.

The attention of the officers seemed to be primarily directed toward convoys. Every so often the people in charge of handling the materials stored at the depot would load up some trucks with the goods that were needed at another post in the eastern U.S. The Intelligence office would presumably designate the route and the timing of the delivery. MPs served as armed guards, which was considered by most as a much more interesting assignment than driving around in the snow at SEAD.

Nobody from the MP Company—or anywhere else—ever asked me what we did at the Intelligence Office. If anyone had asked, I would have replied that I had no idea what the officers did. My job was simply to type and file forms.

What they did ask me about was a civilian employed in the Personnel Office, which occupied the other half of the building in which we worked. She was considered—by far—the hottest female on the base and, I venture to say, the hottest in this area of the country. Several guys manufactured various excuses to walk down to our building to ogle her. The MP’s all worked shifts, which meant that everyone in the company had off-duty time available during business hours every day to devote to visits to the Personnel Office. Quite a few made a habit of it, but no one made any headway.

My co-workers and I had some mundane dealings with the Personnel Office. For example, we sometimes borrowed or lent some supplies. Our involvement with this lady, who was always personable, convinced us that she had no interest in the MPs.

The first day that I arrived at my new workspace I noticed one peculiar thing, but I did not mention it until I was fully trained, and we had eliminated the backlog of paperwork. Appended to one of the walls near the doors to the two offices was a sign that read “Intelligence Office”. I proposed to the PFC that we erect by the door that everyone always used to get to our work area a similar sign that indicated that our area was the “Stupidity Office”. We designed, created, and posted a rather realistic sign. The CIO and AIO got a chuckle out of this, but, needless to say, they made us take it down.

The 201 files for all of the military personnel on the base were stored in our office. I don’t know why; we never consulted them. They contained everyone’s test scores, deployment history, and lots of other things. I was often bored, and I occasionally looked through them. I was more curious about the scores on the Language Aptitude Test, which I had taken at Fort Polk in October, as described here. I scored 73 points on that test. In all of the folders that we had I did not find any other score above 10.

I was also interested in the GT scores. I had heard that the minimum score for assignment to the MP MOS was 90. Only one person in the 295th MP Company had a score that low, and it was the the highest-ranking NCO on the base, Top, our First Sergeant. I was surprised to find that no one had a higher score than mine. At least one guy in E-10-4, our AIT company, scored higher.

The most interesting 201 file of all belonged to Capt. D’Aprix. It had page after page referring to an incident that happened a few years earlier at some other post. Evidently it was all worked out in the end; his assignment at SEAD had entailed a lot of responsibility at a top-secret installation. The exact disposition of the investigation was not detailed in the folder. I never mentioned a word about this to anyone.

The lieutenant in the Intelligence Office invited me to his (and his wife’s) house for supper once. I don’t know what the occasion was. He was an enthusiastic audiophile. He played some music on his reel-to-reel tape player. I asked if the sound quality was a good as on vinyl records. He said that it was “probably better”. It probably was better after the record had been played a large number of times. I never have been able to understand how analog recording works under any circumstance.

I don’t remember what kind of music he preferred.

I hung around some with my co-worker, the PC. He was the first classical music aficionado that I had encountered in the Army. He played some of his Peter Schickele records for me. I became a pretty big fan. I subsequently purchased a couple of PDQ Bach albums. While I was isolating during the pandemic in 2020, I listened to the opera The Abduction of Figaro on YouTube (available here) while walking on my treadmill on rainy days.

1. TDY stands for Temporary Duty. No one knows what the “Y’ designates.