1 + 1 = a marketable system? Continue reading

We were very fortunate that IBM announced the Datamaster in 1981, the same year that Harland-Tine (H-T), an advertising agency in downtown Hartford, began its search for a computerized administrative system. Most advertising agencies both produce and place ads. At almost any ad agency that was large enough to consider automating, those two functions were assigned to separate groups of people. All previous low-end (under $20,000) IBM computers had no way for two users to share data. More details about the Datamaster can be read here.

1981 was also the year that Sue and I moved back to Connecticut. We were also fortunate that Harland-Tine happened to have the same accountant, Dan Marra from Massa and Hensley, that TSI used. Dan told Dave Tine, the president of Harland-Tine about the time and materials billing system that we had written for his firm. As Bob Dylan sang in “Idiot Wind”, “I can’t help it if I’m lucky.”

The unique nature of advertising agencies is described here. The system that we designed for Harland-Tine is described in considerable detail here.

The installation, which began in December of 1981, went pretty well. Westy Jones1, the office manager, oversaw the installation. In phase 1, which lasted about six months, the system consisted of a job costing module, production and fee billing, accounts receivable, accounts payable, and general ledger.

Near the end of the first phase Sue worked with the people at H-T to generate some publicity for both companies. The Basic Society News, a tabloid-sized monthly newspaper dedicated to the Datamaster community, published on the front page of its August 1982 edition a rather detailed account of the installation. It was a really nice write-up with well-chosen photos. We showed it to whomever we encountered.

Until I reread the article for this blog entry, I had forgotten that H-T had also purchased a second Datamaster to use for word processing. The Datamaster had outstanding WP software, but I don’t remember ever having seen a daisy-wheel printer in H-T’s office. The Datamaster’s dot-matrix printer did have a “letter-quality” mode that sort of filled in the dots, but I would not expect any advertising agency to settle for that. Agencies are all about presentation, and dot-matrix output has never really been considered appropriate for important communications.

The second phase of the installation involved the module for media scheduling—including insertion orders, media billing, and media payables—and cost accounting (client profitability). My recollection is that H-T was able to use most of what we had developed for Potter Hazlehurst without significant changes.

I am pretty sure that H-T purchased the 30MB hard drive when they for the second phase. I don’t remember whether they purchased a third Datamaster for the media department. They might have used the one that had originally been intended for word processing.

Considering how much time that I spent on this project, I have surprisingly few vivid memories. Westy hired Diane Ciarcia2 as a bookkeeper and primary operator of our system. She was, thank goodness, easy to work with. She was good at explaining why she didn’t like something that the software did. So, we were able to make the system rather easy to use without too many missteps.

At about the same time that Diane was hired, Sandy Bailey, a wise-cracking New Yorker, was hired as Director of Finance. She and I got along very well. She must have still been there in 1988. I remember remarking that we were furiously pitching the advertising department at Macy’s in New York. She said “If you get Macy’s, you’re all set.”

In 1984, I think, Harland-Tine merged with another Hartford agency the name of which escapes me. The other agency had been one of the very first agencies in the country to automate. Fortunately for us, their system ran on an outdated IBM 5120. So, the new agency, which set up shop in H-T’s office space, continued to use our software.

The new agency was named Harland, O’Conner, Tine, and White3. I never met O’Conner; I don’t even know the right pronoun to use. I occasionally saw Will White4 in his office, which contained several copies of The Sunfish Book that he wrote. I guess that it contained all that you ever need to know about a type of sailboat that I, a native of Kansas, had never heard of. You can still get a copy on Amazon.

Diane Ciarcia left the agency during this period. A young lady from Jamaica was hired to replace her. Because the system was rather stable by this time, we did not need to work closely with her. Eventually someone discovered that she had been issuing checks to accounts that she had opened under various reasonable-sounding names and booked them as production expenses for the agency’s largest account, Hitchcock Chair.

She was not able to run this scam for very long. Dan Marra discovered discrepancies using the month-end reports that our system produced. He credited the audit trails that the system provided with unearthing the scheme. H-T definitely fired her. I don’t know if she was ever prosecuted.

I have one other strong memory of TSI’s first agency installation. This was the beginning of the period, which lasted for more than two decades, during which I consistently worked long hours often seven days per week. I also needed to be very alert whenever I was working. It was very easy to make catastrophic mistakes, and, as always, nobody checked my work. I had become dependent on help from coffee, especially when I was on the road.

I remember wandering into Harland-Tine’s kitchen5 one morning. I poured myself a cup of bitter black caffeine and ported it back to the accounting area. When the first few drops hit my tongue I almost spit them back into the cup. Evidently someone thought that it would be “a nice change” to add a little flavor.

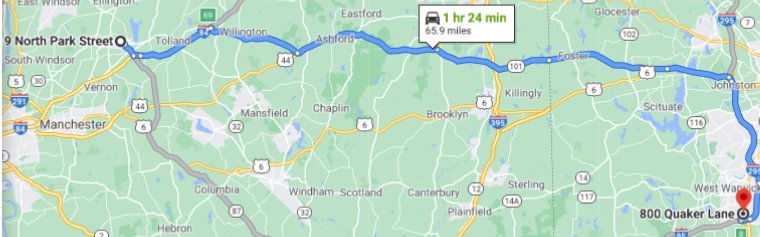

The second ad agency that we landed was Potter Hazlehurst Incorporated (PHI) of East Greenwich, RI. As I recall, they responded to a mailing that we did in 1982. Sue and I drove to their office on Route 2, where we met with Russ Hahn, the office manager, and Bruce Brewster, the accounting manager. Russ said that he liked what we had done, but they also needed a system for media. He also said that they needed to be able to see a summary of the profitability of each client on one report. He showed me what he did by hand for Herb Sawyer, the agency’s president.

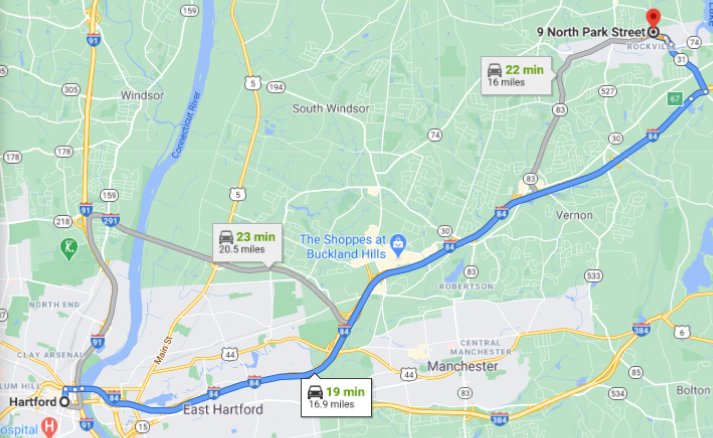

We drove back to Rockville and drew up a proposal. IBM proposed two Datamasters and the hard drive that acted as a server for both data and programs. One computer was designated for accounting and one for media.

On the second trip we met with Herb for lunch, which was served all’aperto. He had not been available to meet with us on the first visit. I was almost as nervous as I had been back in 1962 in my first debate in high school, which is described here. Herb was friendly but serious. I could see that he had some doubts about our ability to pull this off. In the end he signed the contract, and we went to work.

A very fortunate thing for us was that PHI billed all of its media in advance. For example, they billed in the month of November the ads scheduled to run in December,. We designed the system so that prebilling the media was the norm. This helped us in the future in two distinct ways.

- It was much easier to accommodate billing in the same month or a later month than it would have been if we had started with the assumption that the ads had already run and tried to come up with a way of handling prebilled placements.

- It gave us a valuable selling feature. If the agency already prebilled their media, the system could handle it. On the other hand, if it did not, using our system gave the agency the opportunity to try to convince their clients that they should get the invoices in the preceding month so that they paid in the month that the ads ran. In those inflationary times, receiving the money a month or two earlier could be a big factor.

A difficult decision had to be made about the design of the media scheduling system. The different types of media differed greatly. For example ads in print media generally ran only once in an issue of a publication. Broadcast ads almost always ran repeatedly, and most of the time the date and even the program might not be specified. The size of a print ad was measured in column inches. The size of a broadcast ad was measured in seconds. The most surprising thing to me was the “broadcast calendar” that began every month on a Monday.

Furthermore, some types of ads, like billboards or yellow page advertising were sui generis.

On the other hand, it would be easier for the accounting people if the important financial information was in one place. Data entry for billing and payment would be easier, and the programs would run faster.

I decided to designate one file in which all ads were defined. It contained all the financial information and all of the other information for print ads. The fields that were peculiar to broadcast were kept in a separate file. Eventually we created a file for yellow pages, too.

The key to the ads file was the client number, the ad number (usually, but not always the production job number), and a one-character version code to distinguish different sizes of the same basic ad. I never regretted handling media this way.

I spent many days at PHI. I remember every inch of the drive. Most of the morning drives were toward the east. The sun was directly in my eyes. The return trips were mostly due west, and the sun was again in my eyes. I did not own prescription sunglasses. If there were clip-ons available, I did not know about them. It was brutal.

There was not much in the way of retail between Rhode Island and Rockville. On return trips I would almost always stop at the drive-through window of the Burger King on Route 101 in Killingly, CT. The consistent part of my order was a large Diet Coke to keep me alert for the rest of the journey.

If, as often happened, it was late, I would also order a whopper. One time they had a special on “Bullseye burgers”, which were two regular BK hamburgers that were a little thicker than usual and cooked with Bullseye barbecue sauce. The burgers were placed on a long roll and topped with bacon. I ordered one, and I really liked it. Ever since, whenever I cook burgers for myself on the grill, I mix Bullseye barbecue sauce in with the ground beef before cooking.

Incidentally, I have very long fingers. At the time BK advertised that “It takes two hands to handle a Whopper.” I can assure you that I was easily able to drive while holding any BK sandwich in one hand. It did get a little clumsy if I had to change gears on my Celica.

I remember that one time I worked so late that I had to stay overnight. PHI arranged a room for me at a motel in North Kingstown, the next town to the south. It was run by an Indian couple (a rarity in New England in the eighties) with forty or fifty children who had the run of the place. It was an unusual experience for a Kansan, but I did not encounter any difficulties.

I cannot remember much about any of PHI’s employees other than Russ and Bruce. I remember noticing that over half of them had Italian names.

Bruce was a little younger than I was. He was a big guy. He was really into sailing. He had a boat of his own, and he devoted most of his spare time to it. He also disclosed to me that he would really like to be a crewman on a yacht that competed for the America’s Cup.

Russ was a few years older than I was. He was a bit of a fuddy-duddy, but he always took me to lunch. I really appreciated that. When the agency’s fortunes began to slide in the nineties, he was one of the first employees to be laid off.

I am not sure of the year in which PHI closed its doors for good. At the very end Herb Sawyer was operating the Datamaster by himself and calling us for help in closing the books. I found this rather sad.

When the PHI installation stabilized, we no longer had two customers with separate systems. We had two diverse advertising agencies using customized versions of the GrandAd system. I was fairly confident that we could market it successfully.

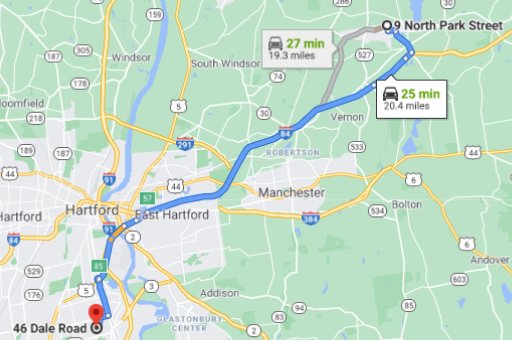

1. I think that Westy’s last name is now King, and in 2021 she resides in Enfield.

2.Diane’s married name is Carrabba. In 2021 she apparently lives in Bloomfield.

3. The accepted abbreviation was “Hot W”. If I had been asked my opinion, I would have suggested putting Mister White first and using “White hot” for short. It is probably a good thing that they didn’t. Shortly after incorporating, they changed the name to Harland & Tine & White.

4. I think that Will White is living in Arcadia, FL, in 2021.

5. It was a real kitchen, not just a place to make coffee and keep lunches. Susan Harland often prepared gourmet meals for clients and prospects.