Home waiting to be drafted. Continue reading

I flew home to KC. In those days the airlines had student-standby rates that were very affordable. My parents picked me up at the Municipal Airport, which is right across the river from the downtown area. Landing from the west was a terrifying exercise in dodging skyscrapers, but it was actually more dangerous to land from the east. If you overran the runway even a little, you might end up in the Missouri River. All my records and my AR speakers also made it home, but I don’t remember how.

I flew home to KC. In those days the airlines had student-standby rates that were very affordable. My parents picked me up at the Municipal Airport, which is right across the river from the downtown area. Landing from the west was a terrifying exercise in dodging skyscrapers, but it was actually more dangerous to land from the east. If you overran the runway even a little, you might end up in the Missouri River. All my records and my AR speakers also made it home, but I don’t remember how.

I had nothing scheduled for the entire summer. My parents lined up one task for me—painting our house. I planned to just hang around until I got drafted, and I also hoped to play a lot of golf. I also watched the mailbox closely.

My report card for my last semester at U-M (the first time) arrived shortly after I did: I got an A (speech self-study), a B (Russian lit), a C (anthropology0, and a D (linguistics). I was greatly relieved not to see any E’s or I’s (incomplete). Michigan issued E’s where everyone else issued F’s. So, as expected, my very first semester’s average was my best, and my last semester’s was my worst. But it was good enough.

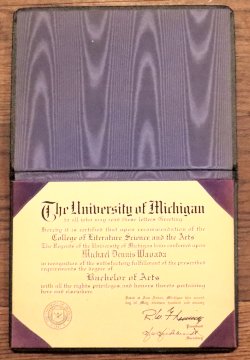

My diploma arrived a few days later. I finally got a chance to look at my transcript a couple of years later when I applied for jobs. Nothing on it indicated that my excess hours in math would have affected my graduation. Maybe I could have dropped the Russian and linguistics classes and still graduated. I needed to enroll in four courses to be a full-time student, a requirement for intercollegiate debate, but nothing prevented withdrawals. Of course then I would have had to explain to the parental units why they had to pay for four courses when I only really took two. That might not have been too pleasant. I think that it all worked out for the best.

My diploma arrived a few days later. I finally got a chance to look at my transcript a couple of years later when I applied for jobs. Nothing on it indicated that my excess hours in math would have affected my graduation. Maybe I could have dropped the Russian and linguistics classes and still graduated. I needed to enroll in four courses to be a full-time student, a requirement for intercollegiate debate, but nothing prevented withdrawals. Of course then I would have had to explain to the parental units why they had to pay for four courses when I only really took two. That might not have been too pleasant. I think that it all worked out for the best.

I wondered to myself how in the world I managed to get a B in that Russian lit class. Clearly those papers that I saw people turning in must have been voluntary and clearly not much attention was paid to attendance at the recitation sections that I completely avoided. I must have also aced both tests.

There was one other possibility. Perhaps the professor was both a caligrapher and a Detroit Tigers fan. Maybe he really gave me a D, but it was misinterpreted as a B.

There was one other possibility. Perhaps the professor was both a caligrapher and a Detroit Tigers fan. Maybe he really gave me a D, but it was misinterpreted as a B.

I also received an envelope from the Society of Actuaries with my test results. I was astonished to see that I scored a 6, which was the lowest passing score. I somehow passed the probability and statistics test without answering a single statistics question!

I received nothing from the Selective Service in June, July, or August.

As a freeloader I could hardly complain about painting the house or any other mundane chore—mowing the lawn, trimming bushes, weeding the roses, etc.— that I was asked to do. I probably grumbled to myself while I was doing them.

My dad’s company provided him with a membership in the Blue Hills Country Club, well to the south of us and on the Missouri side. Dad was a VP in the sales department and was expected to entertain agents and other business associated. The club had a swimming pool and a golf course, but the only feature that interested me was the golf course, which I was allowed to play on for free. I took advantage of that feature as often as I could. I sometimes played with my dad on weekends and with my mother on weekdays. A few times my dad took a day off, and all three of us played.

Occasionally I played by myself. I was very careful not to impede or hurry anyone. I was a courteous guest.

Summers in KC are hot. On one such day I was playing by myself, as always carrying my clubs. I finished the front nine with an indifferent score and bought a coke. I then walked over to the tenth tee, from which point almost the entire back nine was visible. I was surprised to discover that no one at all seemed to be playing. This was puzzling. There was no indication of a special event.

With the course to myself I played three balls. This was strictly prohibited, but if I saw anyone approaching I would just stop doing it. I certainly would not be holding anyone up. Even playing three balls, I could play faster than any twosome in a cart.

I finished the round and walked past the clubhouse and the putting green. The assistant pro, Rick, was doing some maintenance on the putting green. I called to him and asked where everyone was. He said, “Are you kidding? It’s 106° out here.”

I honestly had not really noticed. In those days I had almost infinite tolerance for heat. I almost never wore shorts.

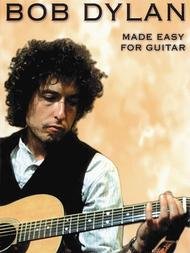

My sister Jamie had just finished the eighth grade. She was a lot more socially active than I ever was. She could also play the guitar. She had a book of Bob Dylan songs, and I could do a passable imitation of the Nobel Prize winner. When I sang in my own voice I always went off-key at the break, but I could pull off the songs in her book pretty well using my Dylan voice. I remember “The Times They are a-Changing” and ‘Mr. Tambourine Man” in particular.

My sister Jamie had just finished the eighth grade. She was a lot more socially active than I ever was. She could also play the guitar. She had a book of Bob Dylan songs, and I could do a passable imitation of the Nobel Prize winner. When I sang in my own voice I always went off-key at the break, but I could pull off the songs in her book pretty well using my Dylan voice. I remember “The Times They are a-Changing” and ‘Mr. Tambourine Man” in particular.

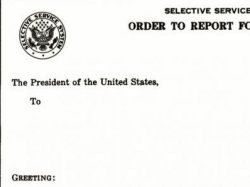

The letter from selective service came in September. It did not begin with “Greetings,” as was commonly reported, but with “Greeting:”. I had to report for my induction physical at a building in downtown Kansas City on Monday, October 5, a day that will live in infamy. My mother drove and dropped me off. I did not see her again for eight weeks.

The letter from selective service came in September. It did not begin with “Greetings,” as was commonly reported, but with “Greeting:”. I had to report for my induction physical at a building in downtown Kansas City on Monday, October 5, a day that will live in infamy. My mother drove and dropped me off. I did not see her again for eight weeks.

The exam was a complete joke. There were a few dozen of us. About 30 percent of the guys were carrying briefcases or satchels with documentation of some real or imagined ailment. All (or at least nearly all) of these people were declared 4-F. I suspect that fifty years later not many people realize how widespread this practice was. More than a few doctors were willing to attest to very questionable ailments like bone spurs.

The rest of us passed. Some people found out that they were color blind. Other than that, the doctors (or whatever they were) basically counted our limbs and stamped us Grade A if we were not missing any.

A common misconception was that they rejected men with flat feet. If I had amputated my toes (some people did!), mine would have resembled Donald’s or Daffy’s. Here is how the foot examination went: We all lined up facing away from the doctor. He called out “Raise your left foot; right foot; thank you.” The pause for the semicolons was no more than two seconds. Many guys never even got their left foot raised.

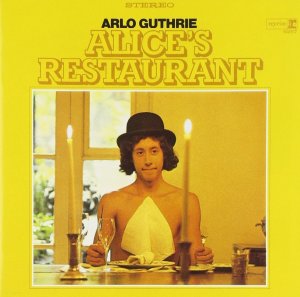

Arlo Guthrie and the movie Stripes claim that they asked about ever being arrested. If so, I don’t remember that.

Arlo Guthrie and the movie Stripes claim that they asked about ever being arrested. If so, I don’t remember that.

They measured me at 6’1″, 145 pounds. I told you that I was skinny.

There were maybe twenty or thirty of us. I expected to be taken to the nearest training location, Fort Leonard Wood, about 200 miles from KC. Instead they flew us to Fort Polk, LA, which was 680 miles away. The base had an airfield, which was where we landed.

I remember that one guy announced that he wanted to be a butcher. He thought that this would be a good way to avoid going to Vietnam. The sergeant who was escorting us advised him that that would be terrible duty, and he should try for something else.

Heretofore I had led a quite comfortable existence that was rather easy to comprehend. The next eighteen months and five days would unquestionably be the most bizarre of my life.