My fifteen seconds of fame. Continue reading

Northeast magazine was a “Sunday supplement” for the Hartford Courant. In April of 1989 the magazine sponsored a contest to celebrate the one hundredth anniversary of A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, which was written when Mark Twain and his family lived in Hartford. Each contestant was asked to write a story of 5,000 words or fewer that updated Twain’s tale. The first prize was a two-week trip to England. I had never been anywhere on the east side of the Atlantic. I felt ready.

This contest appeared to be right in my wheelhouse. I was pretty sure that I had read the book when I was a kid; I certainly had seen the movie with Bing Crosby. I went to the library and checked out the book. It took me a couple of weeks to read; I was surprised by the dark tone and the carnage at the end. If I had read it in school, I was pretty sure that I would have remembered those scenes and discussed them with my friends. Young guys like to envision massive destruction. Maybe I only read the Classics Illustrated version.

I had a month or two to write my story. Who would be the protagonist? The people from Connecticut with whom I was most familiar were in advertising or computers. I decided to go with an ad agency executive who knew just enough about computers to be dangerous.

At that time the big controversy in the advertising community was whether agencies were required to charge Connecticut’s sales tax on any or all of the billings1. Some did, and they bitterly resented those who did not.

I contrived the deus ex machina for moving the action from the Land of Steady Habits to Arthurian Britain by conflating the confusing roads around the north meadows, a ghastly fog that I endured one evening, and a huge tree that I had seen growing in an intersection in Canton.

The WWF (now called the WWE) was a client of CDHM Advertising, one of the users of TSI’s GrandAd system. When I combined wrestling with focus groups, the plot rather quickly came together. Coming up with an ending was the really hard part. I wrote one, but I wasn’t a bit satisfied with it. Has any time-travel story ever had a satisfying ending.

I never wrote anything out in longhand. I composed it in my head while I was jogging, which I did during my customary long lunches and in the evening.

I keyed the text in on the Datamaster that was sitting on a table in the entryway between the garage and the house. Attached to it was the daisy-wheel printer. I seriously doubt that anyone in 1989 had access to better equipment for writing a story. I produced at least ten drafts.

I printed out a copy of the final version, which I entitled “Sir Consultant’s Strategic Plan”. I counted the words on the first page and multiplied by the number of pages2. It was about 5,000, maybe a little longer. Would they really check? I mailed it to Northeast magazine well before the deadline.

At some point in the fall, someone from the Courant called TSI’s office and asked to speak to me. She said that they wanted to publish my story, and she asked for permission to do so. Of course I agreed.

A few hours later I received a second phone call. This time Lary Bloom3, the editor of the magazine, was on the line. Chris Vegliante answered the phone and put Lary on hold. When she told me who was on the other end, she also added, “You won the contest, didn’t you?”

Lary informed me that I had indeed won the contest. He told me that there had been over two hundred entries, some from professional writers. He asked me if I had ever thought that I might win. I couldn’t lie. I had worked hard on it. I thought that it was a really good story, the best that I had ever written. Never mind that at that point in my life I had written almost nothing beyond technical manuals, TSI’s marketing and sales materials, and a few papers in graduate school. I had never even taken a single English class in my ten and a half years in school. I must have been very arrogant. I simply answered, “Yeah, I did.”

Don’t get me wrong. I was on a cloud for at least a week. I considered winning the contest one of the greatest accomplishments of my life.

Lary asked me to come into the office of the Courant on Broad St. to talk about it. When I arrived he warned me that I could not use “schmuck” or “schlub” because they were curse words in Yiddish. I looked both of them up at the library and decided that he was wrong about “schlub”. I did replace “schmuck” with “cutthroat”. I should have used the wrestling term “heel”, but no one in the wrestling world in 1989 admitted that they had assigned roles. I also didn’t know the industry term for the many wrestlers who always lose televised matches and never appear in major arenas. I subsequently discovered that the accepted description is “jobber”.

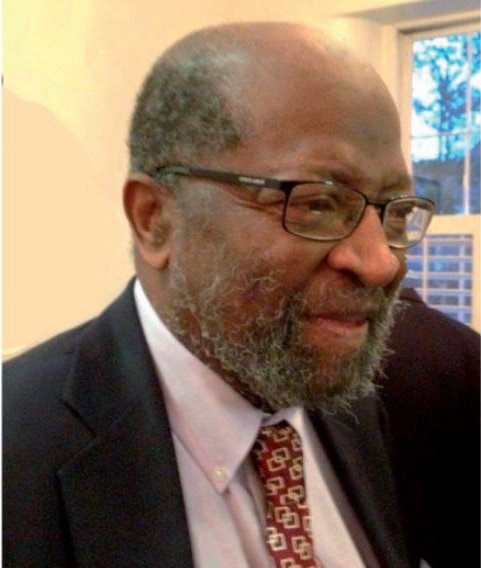

Lary emphasized to me that the voting for the prize was very close. He said that one judge, Dr. James A. Miller4, a professor of literature at Trinity and Wesleyan, had lobbied hard for my story, and that had ultimately made the difference. The other judges were:

- Justin Kaplan, author of Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain.

- David E. E. Sloan, author of Mark Twain as a Literary Comedian.

- Garret Condon, arts editor (and former book editor) of the Courant.

- Dorothy A. Clark5, president of Literacy Volunteers of America.

- Kamala Devi Dansinghani, an honor student at East Hartford High School.

Lary asked me if I had counted the number of words. I told him about my arithmetic approach. He told me that I absolutely must carefully count the words of the final version before they published it. He assured me that some of the other participants would check it and would raise a stink if it was too long.

He let me make whatever changes that I wanted. I tried hard to devise a better ending, but I did not have much luck. Instead I did a lot of work on the opening scene. I was pretty well satisfied with the results. When I reread it for this blog entry, I still liked it. Needless to say, there were a few passages that I would have changed.

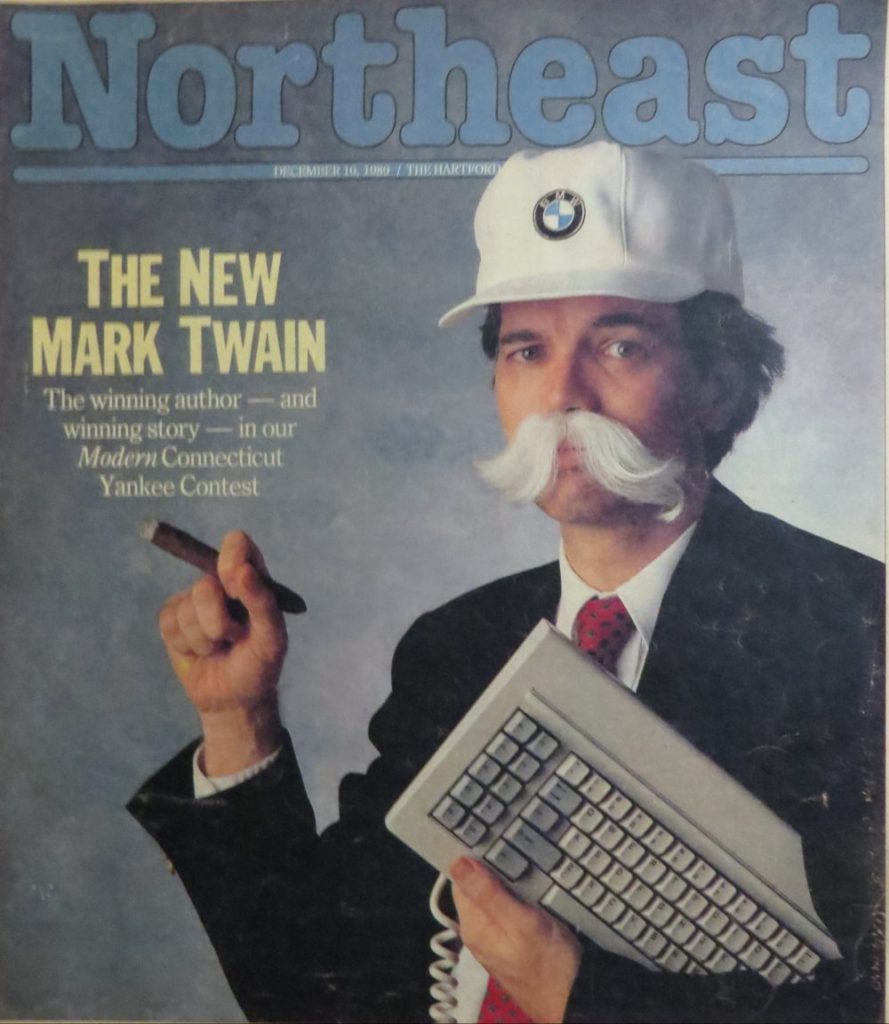

Lary gave me three additional assignments before the article was published in December. The first was to go to the studio of a designated professional photographer (whose name I don’t remember) for the cover shot. I was told to bring a keyboard with me. He stuck a fake white mustache on my upper lip and fitted a white ball cap that he must have obtained from a BMW dealer. He wanted me to light a cigar and smoke it, but I balked. The idea of putting lighted weeds in my mouth has always been abhorrent to me. I agreed to hold it after he lit it.

While I was engaged in this, a friend and client of mine, Putt Brown, came into the photographer’s office. I had spent quite a bit of time with Putt a few years earlier, and I recognized him immediately. He did not recognize me at all, and he was astounded when I told him who I was and what I was doing there.

For the second assignment I had to drive to the studios of Connecticut Public Radio. There I met Phyllis Joffe6, whom I had heard on the radio many times. She interviewed me about my story, and she asked me to read a couple of passages, including the “all-knighter” section that does not work on radio at all. The thing that I remember the most from her interview was that she thought that my style was more reminiscent of Raymond Chandler than Mark Twain.

I had read every word that Raymond Chandler ever wrote. I took what she said as a compliment. I loved his style, but I did not try to emulate it. I tried to write the way that a smart-aleck ad executive would in the eighties. When making a pitch to a client he took on a totally different persona. When he was disclosing his private opinions of those around him, he was often sarcastically dismissive. It wasn’t my style7; it was Ambrose’s.

The interview aired on National Public Radio on Sunday, December 10, the same day that the story appeared in the magazine. I think that it was on Weekend Edition, but I could be wrong.

The third assignment, to which Sue was also invited, was to appear at the Mark Twain House one evening in early December. It was a special meeting of the Samuel Clemens Society, which promotes the activities of the museum on Farmington Ave. The attendees were there to witness Lary announcing the winner of the story contest.

Before the event began I was somewhat surprised to see Frank Lord8, who was, as I recall, the president of the society at the time. I knew Frank quite well from the two years that I had worked at the Hartford Life, as described here.

When, after fifteen plus years, Frank saw me and Sue, he blurted out, “What are you doing here?”

When I told him that I had won the story contest, he was certainly stunned. He did not even know that Sue and I were back in Connecticut.

At some point in the event Lary introduced me to Dr. Miller. I may have met one or two of the other judges as well. I don’t recall any of the small talk.

The story was published in the Northeast magazine dated December 10, 19899. We subscribed to the paper. As soon as I awoke, I retrieved the paper from the driveway, extracted the magazine and read the story. I found two mistakes. I have footnoted them in the copy that is posted here. They bothered me, but they did not really disrupt the story.

I remember the reaction of my best friend, Tom Corcoran, after he had read the story in the Sunday paper. “I didn’t think that you had it in you, Mike. I don’t know why.”

Sue’s sister Betty asked me to do a dramatic reading for her and her friend, Jeffrey Campbell. Others may have also been sitting at the table with them. Everyone seemed to laugh in most of the right places.

Sue and I flew to London in February of 1990. That adventure is described here.

1. While I was writing the story for the contest, the state clarified the law. You can read the notice here.

2. It never occurred to me at the time that the Datamaster may well have had a word-counting feature. Does anyone still have one with IBM’s word processing software? Could you check for me?

3. Lary Bloom retired from the Courant in 2001. His LinkedIn page, which can be viewed here, says that he lives in Chester, CT.

4. Dr. Miller died in 2015. His obituary is here.

5. Beginning in 2006 I played bridge with Dorothy Clark many times at the Simsbury Bridge Club, once as a partner and many times as an opponent. I did not recognize her name at the time, and she apparently did not recognize me. She died in 2018. Her obituary is here.

6. Phyllis Joffe died in 2002. Her obituary is here.

7. My other substantial piece of fiction, which can be read here, would remind no one of Raymond Chandler.

8. Frank Lord died on July 3, 2020. His obituary is here. His LinkedIn page, which lists most of his roles in Hartford, is here.

9. The Courant let me have ten copies. I still have two or three.