My stint as a clerk-typist and combat duty in the New Mexican War. Continue reading

Life was quite different when I started working in the Law Enforcement Office on SBNM. I cannot remember the date, probably in April or early May. It was a standard 9-5 job with weekends off. We all wore the summer dress uniform of a khaki-colored shirt and trousers. I wore black dress shoes instead of boots. I left the nightstick, holster, white hat, and MP armband in my room. Essentially I was now a clerk-typist. I filled out forms and reports for the higher-ups, I occasionally typed a letter for one of my bosses, and I sometimes cleaned up reports submitted by the desk clerks.

In some ways my new assignment was a demotion. On the police desk Sgt. Bailey left some decisions up to me. Policemen on television are often depicted as disgruntled during such “restricted duty”. I, on the other hand, was happy to erect some pretty clear boundaries on my remaining active-duty time in the military. Besides, I never wanted to be a cop. I was still in law enforcement, but only on the back end.

For me the biggest adjustment was in my golfing schedule. In my new job I could play on weekends if I could find someone with transportation to play with. I could also play at least nine holes in the evening with someone working days or mids, but they might want to start earlier in order to play eighteen. In short, I played a lot less.

Furthermore, when my platoon was working swings, there were three-day periods when I could not hang out with and dine with my friends in the evenings. By this time, however, I knew quite a few people in other platoons. Several of the guys on the second floor of the west wing, which I think housed the fourth platoon, spent as much of their free time with us as they did with the guys with whom they worked.

Another disadvantage was the elimination of hours of free time on the midnight shift. I always brought a book with me, and I usually could get in several hours of reading. I had become one of the base library’s biggest customers.

The disadvantages were more than counterbalanced by the fact that I was able to adopt a regular sleeping schedule. This alone improved my mood immensely. Furthermore, I have never had difficulty keeping myself entertained.

One other huge advantage only became evident after the Air Force took over in July.

Three people were working in the Law Enforcement Office when I arrived. The boss was Captain Huppmann. He was fairly young, perhaps 30, and very enthusiastic. I think that he made all the decisions concerning law enforcement on the base. The base commander, Major General Nye1 (Air Force), did not seem to involve himself in the day-to-day police operations. Perhaps he was busy making plans for the merger that was already in the works.

Three people were working in the Law Enforcement Office when I arrived. The boss was Captain Huppmann. He was fairly young, perhaps 30, and very enthusiastic. I think that he made all the decisions concerning law enforcement on the base. The base commander, Major General Nye1 (Air Force), did not seem to involve himself in the day-to-day police operations. Perhaps he was busy making plans for the merger that was already in the works.

Although Capt. Huppmann was not a bit shy about bringing questions and work directly to the clerks, Sgt. Edison, whose rank was Sergeant First Class (E7), was usually our direct contact. I am not sure to what extent he influenced policy. My impression was that it was very little.

Although Capt. Huppmann was not a bit shy about bringing questions and work directly to the clerks, Sgt. Edison, whose rank was Sergeant First Class (E7), was usually our direct contact. I am not sure to what extent he influenced policy. My impression was that it was very little.

The other clerk was named Duffy. I don’t remember his first name. Rank for us was irrelevant, but I think that he was an SP4 when I arrived. He had enlisted, which meant that he faced three years of active duty. He entered the Army before I did, but I would get out a lot sooner. He was not an MP; his MOS was clerk-typist. He was a bachelor who lived in the headquarters platoon area. He was from Quincy, MA. I liked him a lot. He was competent and easy to work with.

Duffy and I seldom had social conversations with either Capt. Huppmann or Sgt. Edison. For us it was strictly “Yes, sir’ and “No, sir” (or sergeant) when they were around. They both had separate offices and lived off-base. I never wondered whether they were single or married.

Capt. Huppmann was too enthusiastic about his job to be popular with the guys in the patrolling platoons. Most of them considered him a lifer and, therefore, inimical. I don’t remember him doing anything malicious or stupid.

One time the captain came to the clerks’ area to complain about a call with which he had to deal. It was from a wife of an NCO who lived in the suburban-style housing on the base. She claimed that MP patrols circled around her neighborhood checking out the women who were sunbathing in their yards. Capt. Huppmann thought that the woman’s position was ridiculous and refused to reprimand the MPs. I must admit (here, not to Capt. Huppmann) that I had engaged in this practice before I was transferred to the Law Enforcement Office.

My only clear memory of Sgt. Edison was the time that he came into our area to talk with Duffy and me about something that was bothering him. He ventured the opinion that at least two MPs were using drugs. Duffy and I made neutral responses that neither confirmed nor denied what he said.

After Sarge left our work area, Duffy and I looked at each other, rolled our eyes, and smirked. Everyone who lived in the MP barracks knew that at least half of the guys smoked marijuana regularly. You could smell it in any hallway. I don’t know about other drugs, but a guy whose name escapes me once got so stoned that he shaved his head. This was before Michael Jordan made it cool; the Army actually prohibited the practice.

The University of New Mexico campus was a short drive from the base, and all kinds of drugs were prevalent there. I don’t know much about the guys who lived off-base, but one of them, Randy Hjelm, was in the second platoon with me. He had obviously been stoned every time he reported for duty. Sgt. Bailey could not send him to deal with of anything important.

I don’t remember much about Duffy. He was younger than I was; he probably enlisted shortly after finishing high schools. I liked working with him, but we did not hang out together. He told me once that he purchased a six-pack of Lone Star after work every Friday. I don’t know how he spent Saturdays and Sundays.

The New Mexican War

For some reason most history textbooks have neglected the New Mexican War. Yes, there was another war going on at the same time. Most of our troops and all of our modern weapons were employed in Vietnam. Yes, the soldiers there were forced to wade through disgusting rice paddies to confront an almost invisible enemy.

Nevertheless, the two pitched battles of the New Mexican War of 1971 deserve more attention, if only for the way that they shaped the values of the valiant men of MPCO SBNM. Furthermore the enemy had dared to trespass on property of Sandia Laboratories the United States government.

The Siege of Sandia Base: Wednesday May 4, 1971, was a typical Albuquerque day—warm, cloudless, and dry with a noticeable wind. I was typing something when someone—I don’t remember who—came breathlessly to the Law Enforcement Office and ordered me to draw a weapon and report to the Day Room. Since the person had a clipboard and had checked my name, I had no choice. I stopped by my room to get my holster, my white hat, and my MP armband. I found a few pieces of notebook paper to attach to my own clipboard. I then joined the rest of my platoon and a bunch of other MPs in the Day Room.

A couple of truckloads of MPs were soon transported to the battlefield. When the trucks stopped, we could see that almost two dozen peace-crazed Ghandiists had taken a stand (actually a sit) across a busy street near Sandia Laboratories. Traffic was at a standstill in both directions. The effect was the same as if a huge bomb had exploded in the middle of the street, except that there was no damage at all, and chanting replaced the deafening boom.

The lifers had somehow determined which of them was in charge. That person ordered us to pick up the protesters and to put them in trucks. I don’t remember who gave the order; a soldier in the heat of battle does not concentrate on who gave orders, only on how best to implement them.

The lifers had somehow determined which of them was in charge. That person ordered us to pick up the protesters and to put them in trucks. I don’t remember who gave the order; a soldier in the heat of battle does not concentrate on who gave orders, only on how best to implement them.

As others rushed to pick up and carry away the limp protestors, I, one of the few MPs not wearing fatigues, walked around and checked imaginary notes on my clipboard. I never touched any of the protestors, but I had the same thought as most of the rest of the MPs: “Those guys look a lot like me twelve months ago, and some of them smell like the MP barracks.” Within a few minutes the protestors were loaded in the truck, and the motorists, most of whom were employees of Sandia Labs, continued about their business.

The demonstration was covered on the front page of both the Albuquerque Journal and the Lobo, the University of New Mexico’s newspaper. The latter is available online here. The article in the Journal was very favorable. It cited a few protestors who affimed that they had been treated with dignity and respect by the MPs. They also said that the guys from the Albuquerque Police Department had been a lot rougher with them.

The brass was very pleased with this outcome. A letter of commendation was written for everyone involved, including me and my clipboard. I got to read the letter when the Army let me carry my own personnel folder to my next duty assignment.

It may seem strange that the MPs turned over the protestors to the APD. SBNM had no facilities at all for detaining people. Kirtland AFB had a jail, but it could not have accommodated so many prisoners. Someone must have made arrangements for the transfer. I don’t know the legalities involved. The event occurred on federally owned land, but the whole base is within the city limits.

The Second Battle of Albuquerque: The first battle of Albuquerque occurred in 1970. It is not considered part of the New Mexican War because the enemy in that skirmish was a bunch of students, and students at colleges nearly everywhere revolted in 1970. The National Guard effectively ended that rebellion by gunning down four of them and injured nine others at Kent State while taking no casualties.

The situation in 1971 was much different. It took place in the 60 percent of Albuquerque that is not SBNM. It was described by Aaron G. Fountain this way:

The situation in 1971 was much different. It took place in the 60 percent of Albuquerque that is not SBNM. It was described by Aaron G. Fountain this way:

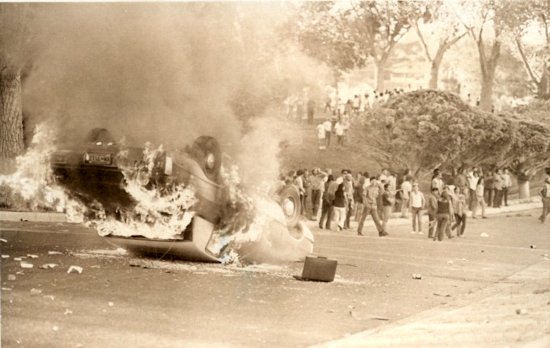

On June 13, 1971, rioting broke out at Roosevelt Park after police attempted to arrest a young man standing in a crowd of several hundred rowdy youth. A small scuffle escalated into a brawl leading officers to fire upon the crowd, wounding at least nine people. Outraged, nearly 500 youth moved into the downtown area where they overturned cars, shattered windows, looted and severely damaged and destroyed buildings. Police attacked rock- and bottle-throwing protesters with tear gas but were overwhelmed. The New Mexico National Guardsmen came into the city to assist officers. After two days of rioting, the city tallied over $3 million in damages. Shocked by the level of carnage, one journalist of the Albuquerque Journal wrote, “It was something you’d think couldn’t happen in Albuquerque, but it did.”2

Despite the sterling record of MPCO SBNM in breaking the siege in May, the APD did not solicit support from our battle-hardened unit. I know for a fact that our officers were closely following the situation and stood ready to aid them. My buddy Al Williams attended an Albuquerque Dodgers game that day. Lt. Hall also was there. When the two met at the refreshment stand, Lt. Hall assured A.J. that “If it gets too bad, we can probably see the smoke from here.”

Google maps shows that even in 2020 the suburbs on the base (bottom) are separated from the Albuquerque residents (top) by only a few hundred feet of scrub land.

In fact, that evening (or at least one evening in that era) a decision was made to deploy troops around the northern perimeter of the base (the Albuquerque side) to serve as a first line of defense in case the insurgents decided to bring the battle to us again. The main gate was closed, and someone went through the barracks ordering off-duty troops to report in uniform to the Day Room. These guys were then armed with rifles3 or .45 pistols and deployed around the perimeter, mostly in suburban SBNM backyards that were separated from suburban Albuquerque back yards by two or three hundred feet of undeveloped land.

An hour or two later the situation evidently calmed down. Trucks were dispatched to pick up the sentries. They missed one guy, who had to walk back to the PMO the next morning after a long cold night guarding someone’s back yard.

I did not participate in this maneuver. I was alone in my room when someone knocked loudly at the door and announced the deployment. I said nothing, turned off the overhead light, and exited through the window. I then ambled over to the base’s theater and paid $.35 to watch a movie the name and contents of which I do not remember.

1. General Nye died in 2019 at the age of 100. So, he would have been around 52 in 1971.

2. This article is from the Latino USA website. It is posted here.

3. The MP Company had no M-16’s. The only rifles in the armory were World War II-era M-1’s that were used for ceremonial purposes such as firing 21-gun salutes at military funerals. Only a few guys had ever fired one.