Moving to 7B. Continue reading

By 1999 the office in Enfield no longer seemed suitable for TSI. We had been doing more training there than we anticipated. Fortune 500 companies had been sending employees to be trained for three or four days in a converted barn with no training room. My office, which was already also serving as the home of our AS/400s, System/36s, and their system consoles, had to be used for the training sessions, It did not give us a professional appearance.

There were many other reasons that Denise Bessette (introduced here) and I wanted to move. In the first place, since Sue Comparetto was no longer working in the building much (explained here), I felt uncomfortable being in a building owned by her father and shared with his company and Sue’s siblings, all of whom worked for the Slanetz Corporation.

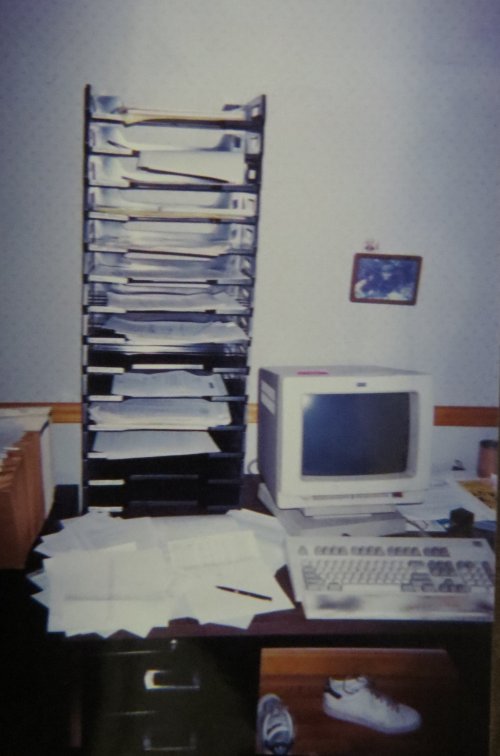

I was sure that Denise would be happy to move into an office that she designed rather than the one that she had shared with Sue. Sue was hardly ever there, but many of her bags, boxes, and piles of her junk were still in evidence.

Behind the office building was a lot that was the home of (literally) tons of discarded equipment and machinery, including a fire truck, a blue school bus, a rusty tractor from before World War II, innumerable tires, and at least twenty fire hydrants. These all belonged to some iteration of the Slanetz Corporation. Personally I did not care if they wanted to have a junkyard there, but as the proprietor of the business, I had to think about what our clients thought. If we ever needed to bring someone really important to the office, we would certainly be embarrassed.

One important person whom we wanted to contact quickly was someone to manage our marketing. Doug Pease (introduced here) had done an outstanding job working out of what was supposed to be a closet, but we could not expects someone who could acquire contracts with billion dollar corporations to do so.

We also needed to rewire our office to allow easy access to the servers from PCs and to use the Internet. Denise took charge of all of this, and she preferred to do it from scratch rather than to retrofit the scheme onto what we had.

Another neglected priority was the furniture. We had a mishmash of second-hand pieces that we had accumulated over two decades. In general we wanted a more functional and more modern working environment. Jamie Lisella (introduced here), who was doing the administrative and bookkeeping functions, needed a better setup. We also wanted to move Sandy Sant’Angelo (introduced here), who dealt with support calls from clients, an area in which her voice, which really carried, did not disturb the programmers.

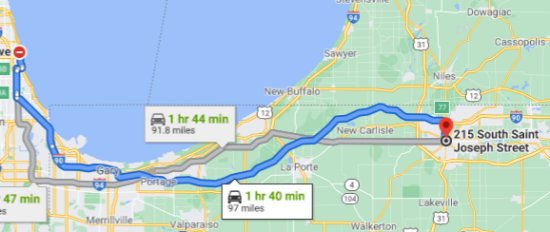

A limiting factor was the fact that Denise lived in Stafford, which was already a twenty-minute drive. Most of the available office space would be towards Hartford and therefore farther for her. She was amenable to increasing her commute a little, but she did not relish the prospect of a two-hour round trip.

Jamie did most of the research into places looking for tenants. I remember that she found a place in a medical building near Kohl’s. Denise and I went to look at the space, which was on the second floor of a building that had mostly medical tenants. I thought that it was OK, but Denise did not like the fact that it was so close to a shopping center where people might be hanging around in the evening. She sometimes worked by herself and did not leave until it was dark.

A place on Hazard Ave. would have been very convenient, but the only space that was available was disqualified for some reason. I never saw the interior of the place. I think that a chiropractor moved in.

My lobbying to move the operation to North Hollywood, CA, (explained here) was dismissed by the other participants in the search.

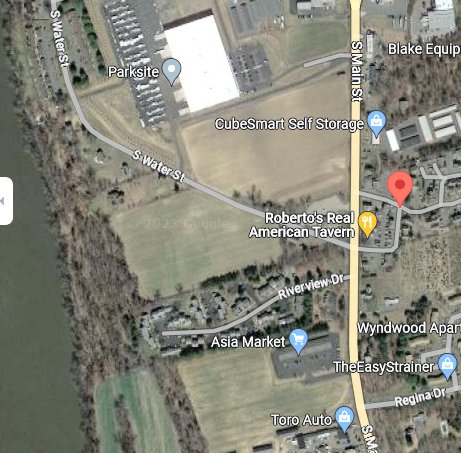

I am sure that Jamie located the site in East Windsor. I remember her saying, “I think that I have found TSI’s new home.” It was in Pasco Commons, a group of buildings that were designed to be homes, offices, or both. Building #71 was owned by Rene (RAY nee) Dupuis, the owner and operator of Tours of Distinction2, a travel agency that specialized in arranging bus tours in New England.

TofD took up the bottom floor, Suite A. Rene wanted to rent TSI the second floor, Suite B. We would be able to add or remove interior walls and shape it the way that we wanted it. There was also a unit in the basement, which he rented as Suite C once or twice.

The location was East Windsor just off of Route 5, a major US highway, and less than a quarter mile from the Connecticut River. The location was quite good. Building 7 had its own parking lot with five or six slots on each side. Two doors opened onto the parking lot, one from Suite A and one from the stairs to Suite B. The rent was not much more than we paid Sue’s father. If the traffic was light I could reach the office in fifteen minutes—my record was twelve.

Preparations: I found some graph paper that we could use to plan where all of the walls and doors would be. We put a conference room, the area for Sandy and the administrative person and the sales office on the south side. The programmers and office equipment were in the middle, and offices for Denise and me were on the north side. The east side had the server room, the kitchen, and the bathrooms. The server room was supposed to be big enough to hold our supplies, too, but somehow we lost a couple of feet of space. Fortunately, Rene allowed us to make a last minute change to wall off an area for supplies and storage.

Denise made most of the arrangements for the transition. The furniture was mostly new, or at least new to us. We got a nice table for the conference room with comfortable chairs and a beautiful bookcase that I claimed when we closed down in 2014. We ordered five phone numbers. The last four digits were 0700-0704, which was convenient. In the entire history of the company no employees—not even Denise and I—ever had personal phone numbers or extensions. I have always thought that that was smart for a company of our size.

The part of the old building used by the Slanetz Corporation had a kitchen, and they let our employees use the small refrigerator. The new kitchen also had a small refrigerator, a microwave, and a table. It also contained a sink, counter, and cabinets, but no stove.

The big move: We did not take occupancy of 7B immediately. The furniture and the new separation panels arrived at separate times. I must have been involved to some extent in the assembly and placement, but I have no distinct memories. I am pretty sure that I brought the computers from Enfield over the weekend in my car. I probably needed some help with the AS/400.

After all the furniture had been received and the equipment collected we moved in and shortly thereafter we had an open house party. I don’t remember everyone who came, but I do recall that Denise’s mother and at least one of her sisters were there.

Someone brought us two nice plants in large pots. Both of them survived our entire stay of more than fourteen years in East Windsor. By 2014 they were both gigantic. I sold them to someone who probably dumped them somewhere and kept or sold the pots.

Life in East Windsor: Before Pasco Commons existed, Jonathan Pasco’s restaurant was an institution on Route 5. TSI had a couple of outings there, and we occasionally entertained clients or others we were trying to impress. I think that we also went to La Notte, an excellent Italian restaurant in the middle of a nearby industrial park.

On many evenings and weekends I went for runs on the roads around that industrial park and the adjoining Thompson Road. I often did as much as ten miles. I sometimes left my water bottle at the Thompson Road entrance. Once I was approaching that spot having completed my first loop. A police car was surveilling the bottle from across the street. When I approached it the officers accosted me and asked what the “device” was. I told them that it was my water bottle. They asked me to take a drink, and I did. This occurred shortly after 9/11, when half of America was paranoid about terrorist attacks.

On one of my runs I aw a very large snapping turtle on grass besidee Thompson Road. Inside the industrial park I often saw wild turkeys and once spotted a bobcat. I also once observed two hawks “doing it” on the ground.

I usually arrived at work before 6:00 in the morning. I worked for an hour or two and then took a nap on a mattress from a portable cot that Sue had bought for camping and only used once. On a couple of occasions someone was surprised to find me asleep on the floor of the server room.

Every few days I would go to Geissler’s grocery to buy Red Delicious apples and diet cola in two-liter bottles. On one of those occasions I ran my Celica into the side of a Lincoln. I was driving on the exit lane on the right in the photo. The Lincoln was traversing the lane in the foreground.In my hundreds of trips to Geissler’s I had never seen a car using that lane.

The policeman investigating the accident did not give me a ticket. He said that the East Windsor police were called for accidents there every week. Eventually they reconfigured the parking lot to prevent the kind of accident that I was involved in.

Every day I brought my lunch from home or bought a sandwich or salad at Geissler’s. If the weather was good, I generally ate at a picnic table in a small park by the river. I almost always took a nap after lunch, either in my car or in the park on my notorious mattress.

One of the biggest events in the history of East Windsor occurred while we were tenants there. Walmart opened a Super Center a mile or so north of TSI’s headquarters. The first time that I went there I wondered how they had found so many people who looked like they were from Appalachia.

178 N. Maple: TSI left behind some furniture in the Enfield office. Sue continued to go there on occasion. At one point she obtained a great deal of fabric from someone that she knew. She tried to run a small business selling the fabric for a while.

The Slanetz Corporation made an effort to rent out the space at least once, but as of 2023 it is not in use.

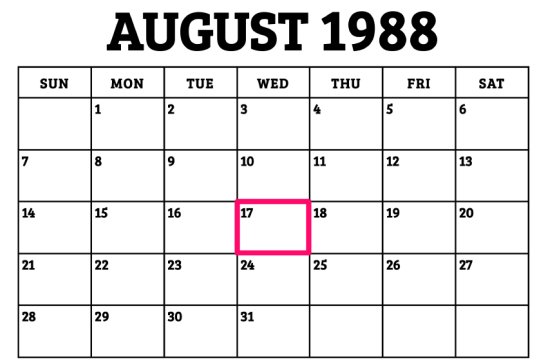

1. When I researched this in 2023, I was surprised to discover that Building #7 was for sale as a “new listing”. All of the interior photos are of 7A, and the one exterior photo shows only the door to 7A. It was weird. It was obvious that something (the other door) had been excluded. I found the photo at right at this website.

2. Tours of Distinction has moved to Simsbury. Its website can be viewed here. When I looked there I could find no information about who owned or operated the agency.