The big fix. Continue reading

In 1999 people were predicting an end to civilization because of the imminent arrival of a new century. Art Bell interviewed a doomsayer almost every night. Key software programs were expected to crash a few seconds into the year 2000.

The calamity did not happen. A few systems probably had difficulties, but no major problems were reported at all. In the late nineties employees and contract workers at companies around the world ad devoted a great deal of time and money fixing or replacing software that would not work as designed in the year 2000. TSI was one of those companies.

The software programs that we had installed at clients and we used in TSI’s office often involved dates. For example, every business that does billing needs to know whether the clients are paying the bills within a reasonable time. This involves a comparison of the date of the invoice and the effective date of the report. The routine that makes the comparison must know the year for both dates. As long as both dates are in the same century, the familiar two-digit version of the year will suffice. However, if the invoice date is in 1999 and the report is run in 2000, the calculation must be adjusted.

This aspect of the problem was relatively simple to solve, but in large systems like the ones that we had installed there were thousands of references to dates. The challenge was to find all the situations that needed to be fixed and to implement the appropriate changes in a manner that minimized the inconvenience to the user.

From our perspective the problem was twofold: the way that dates were stored and the way that dates were collected—from data entry screens or from other files. As we entered the nineties we had three groups of clients: 1) System/23 (Datamaster) users, most of which had extensive custom code; 2) System/36 users, most of which were ad agencies that had a lot of common code, but a mixture of custom and standard programs were stored on separate media for each client; 3) a few AS/400 AdDept users; 4) TSI itself, which used a version of the ad agency system on the System/36.

I decided to inform all the Datamaster users well in advance that TSI did not intend to make their code Y2K-compliant. Most of them were not surprised; IBM no longer supported the hardware. However, the sole user at one customer, Regal Men’s Store, begged us to make their system work in 2000. I replied that it would probably be cheaper for them to buy a new system. As it turned out the company went out of business shortly after year end without purchasing a new system.

Fixing each ad agency system would have been a monstrous job of minimal benefit to anyone. By January 1, 2000, their hardware would have been obsolete for a dozen years. So, I sent a letter to each suggesting an upgrade to a small AS/400. Only a few of them took us up on the offer.

We did create a version of the ad agency software for the AS/400 that was Y2K-compliant. Our employees used it for administrative tasks for about twenty years. We had a great deal of trouble marketing it even to the ad agencies that love their GrandAd systems. Fortunately, by 1994 AdDept sales had really taken off, and we did not really care too much about the difficulties of marketing to ad agencies.

The AdDept system had to work perfectly, and the transition must be smooth. We had already promised a number of users that it would be Y2K-compliant. I intended to spend New Year’s Day 2000 watching bowl games, not dealing with Y2K catastrophes.

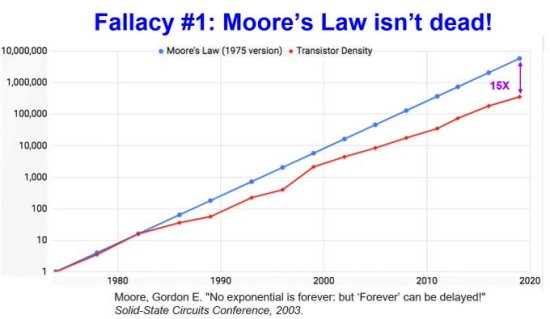

Why, you may ask, was there even an issue with data storage? That is, why were the dates stored in a format that caused the difficulties in calculations? The answer lies in Moore’s Law, the preposterous-sounding claim that the number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit (IC) doubles roughly every two years. In point of fact, the astounding 41 percent growth rate applied to many aspects of computing—processor speed random-access memory, and the ability to locate and retrieve large amounts of data very quickly.

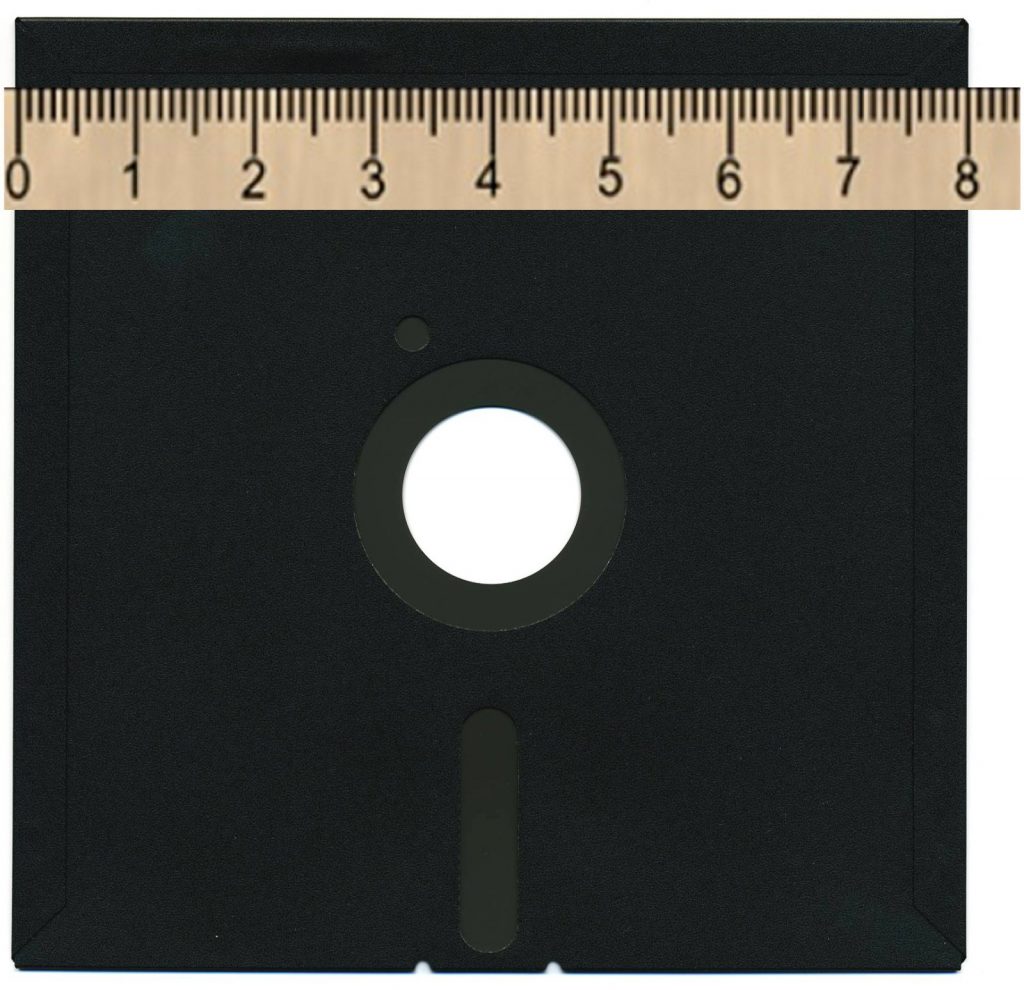

For TSI’s first handful of years in business the clients stored all of their data and their programs on diskettes with a capacity of only one megabyte1. Those users crammed years worth of historical data on these thin slices of film. To put this into perspective, consider this photo of an eight-inch diskette:

Storing the simple photographic image shown above requires more than seven megabytes. So, storing a file of the size of this one image—something routinely done in 2021 by cameras, phones, watches, eyeglasses and countless other “smart” devices—would require (using the technology of the eighties) eight diskettes and perhaps an hour of computer time. Much of TSI’s systems were designed in this era in which both disk and memory were precious commodities. Good programmers were always conscious of the the physical limitations of storing and manipulating data. The prospect of a client’s system crashing because it ran out of space for its data was a nightmare to be avoided at all costs. Everything was therefore stored in the most efficient way possible. The idea of using two extra bytes to store the century occurred to almost no one in the early eighties.

I could think of several possible approaches to the storing of data to circumvent the problem of the new century. The four that we considered were:

- Replace all of the YYMMDD numbers in every data file with eight-digit YYYYMMDD fields;

- Keep the dates the way they were but add a new field to each record with the date in the YYYYMMDD format and use the latter for comparisons, calculations, and sorting;

- Add a two-digit century field (filled in for existing data with 19);

- Add a one-digit century field (filled in with a 0 for existing data).

Rejecting the first option was an easy call. All of TSI’s systems had hundreds of programs that read fields by their position in the record, not by the field name in the database. If the total width of the fields that preceded the field in question, was, for this example, 50, the program read the six-digit date field beginning at position 51. This was not the recommended method, but it had always worked better for us for reasons that are too wonky to describe here. The drawback was that whenever it was necessary to expand the size of a field, it was also necessary to change or at least check every line of code that read from or wrote to the file. This could be an imposing task for even one field. Since a very large number of files contained at least one date, almost every statement that read, wrote, or rewrote data would need to be checked. If it needed to be fixed—or even if it did not seem to need fixing—it needed to be tested thoroughly with data that contained dates in both centuries. We had no tools for the testing, and every situation was at least somewhat unique.

Attempting this for every date and season field was such a large and dangerous task that the only way that I would consider it was if, at the same time, we abandoned reading and writing by position and replaced it with reading by field name. I thought about it, but I decided that that approach would result in even more work and was only a little bit less dangerous.

I reckoned that the other three methods were roughly equal in difficulty and in the amount of time required for implementation. I eventually decided that the one-digit method would suffice.

There was one additional issue in the AdDept system. The first two digits of the three-digit identified the year. So, it was necessary to add a century field for every file that included the season number as well. The season was a key field2 for many files. Fortunately, it did not seem to be necessary to add the century to the construction of any of those keys.

The other issue concerned data entry. Users of TSI software were accustomed to entering dates as a number in the form MMDDYY, the way that dates are commonly written in the United States. The programs validated what had been entered by converting the number into YYMMDD format and checking that each piece was legal. The check for the year normally involved checking to make sure that it was within ten years of the system date. So, every validation routine needed to be changed because the date entered and the system date could be in different centuries.

All of the work was to be done on the AS/400. The first step was to locate all of the files in both the AdDept database and the agency database, which we called ADB, and to add century fields that defaulted to 0 at the end of the files. At the same time, every program that wrote records to these files was found. A peculiarity of BASIC helped us find these programs. BASIC associates numbers with files in each program, and TSI consistently used the same numbers for files. Thus every instance of updating of the job file contained the phrase “WRITE #22”.

A single callable program was written to calculate the century. Its only input was the two-digit year. It was incredibly simple. It set the century to 1 if the year was less than 80 (the year that TSI moved to Connecticut); otherwise it set it to 0. In BASIC it required only two lines of code:

CENTURY=0

IF YR<80 THEN CENTURY=1

This approach will work flawlessly until the program confronts dates that are in the 2080’s. If anyone is still using code produced by TSI when that happens, someone will need to come up with a rule for setting CENTURY to 2. I don’t lose any sleep over this possibility. Yes, you could say that we just kicked the can down the road, but who is to say that roads and cans will even exist in 2079?

A much more time-consuming problem was correcting all of the programs that produced reports or screens in which data was sorted by one of the date or season fields. I set up an environment for the Y2K project that contained both programs and data. Whereas it seemed important to insert the century field into all the affected files as soon as possible, the reports and screens would work fine for a few years and could be addressed one at a time.

I evaluated this part of the project to involve mostly busy work—repetitive tasks with almost no important decisions and no creativity whatever. We had hired a college student to work with us for the summer. I thought that Harry Burt and I could set up the projects for him. Harry, who had experience as a college-level professor, could supervise him and check his work. This method did not work out at all, as is described here, and it used up some precious time.

I may have overreacted to this setback. I decided to make this a very high priority and to assign it to myself. One of the programmers surely could have done it as well as I did, but I did not want to assign it to any of them because I did not want anyone I was counting on to consider their job as drudgery.

So, for several months I spent every minute of time that I could find fixing and testing programs to handle the century fields correctly. A few cases were trickier than I expected, but the coding was completed, tested, and installed before any of our clients started planning for the spring season of 2000, the first occasion that would requir the code.

I am not certain about when this occurred, but at some point I received a letter from, as I remember it, someone in the legal department of Tandy Corporation. It said that the company had received a letter from someone named Bruce Dickens demanding that Tandy pay him a proportion of its gross income every year to license the software that handled the Y2K problem because it must have used the technique of “windowing”, for which he had been issued a patent by the U.S. patent office.

The letter, of which I cannot find a copy, contained a technical description of the term3 as described in the patent and asked me two questions: 1) Did the software that we installed at Tandy use this technique? 2) Would TSI indemnify Tandy Corporation in a lawsuit over its use?

I answered both questions truthfully: 1) “This does not sound like what we used.” 2) No.

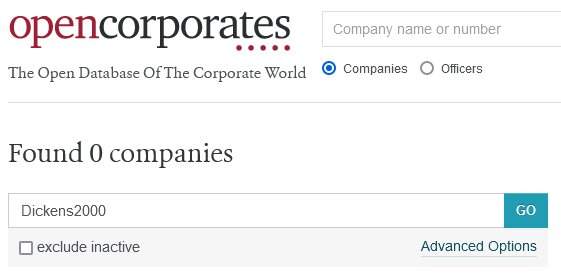

Dickens sent demands for payment to all of the Fortune 500 Corporations. He said that if they did not agree, the percentage of income required for the license would be increased.

I have searched high and low to find out how this situation was resolved. I know that the U.S. Patent Office scheduled a review of the patent, but I could not find a report of the outcome. I also could not locate any information about whether any of the companies that he had extorted ever paid anything to him or the company that he reportedly founded, Dickens2000. I doubt it. I found no evidence that he actually sued any of them either.

If I had been asked directly whether any of our code calculated the century using the year, I would have changed the code listed above to remove the IF statement and simply set CENTURY=1 in all cases and then answered “No”. A few months into 2000 employees of the companies that used the AdDept system no longer entered twentieth-century dates on new items, and the programs only used the code to assign a season when new items had been entered.

We did not charge any of our clients for the Y2K fix. A few people told me later that this was a mistake. Since our customers depended upon AdDept, and there was absolutely no alternative system available, we probably could have gotten away with charging them. The companies may have even set aside funds for this purpose. However, all of the AdDept users had software maintenance contracts, and I considered it our duty to keep their systems operational.

1. A bit is a binary storage unit; it has only two possible values: off or on. A byte contains eight bits, which is enough to store any kind of character—a letter, number or symbol. A megabyte is one million bytes, which is enough to store approximately eighteen Agatha Christie novels. However, it is not close to enough to store even one photograph. Videos require vastly more storage.

2. A key is a set of fields that uniquely identifies a record. A well-known key is the social security number. The VIN number on a car is also a key. A zip code is not a key because neighboring residences have the same zip code.

3. The most readable and yet comprehensive description of the windowing technique that I have seen is posted here. The application for the patent, which was granted to McDonell-Douglas in 1998 (long after everyone had decided on the approach to use), was (deliberately?) designed to appear much more elaborate than the two lines of code that we used.