The Keys of the Kingdom: An Analysis of Matthew 16: 18-19

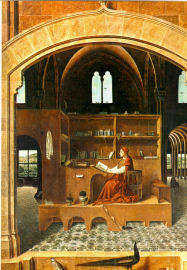

In 382 Pope Damasus I commissioned St. Jerome to translate the Bible from Greek and Hebrew into Latin. Thereafter, Rome relied heavily on Jerome’s rendition of Jesus’s words in Matthew 16:18-19: “And I say also unto thee, that thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. And I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.” These lines are considerably more impressive in Jerome’s Latin (and in English) than in the original Greek. The Greek words for Peter (πέτροσ) and rock (πέτρα) are not synonymous. In Greek πέτροσ denotes a smaller rock than a πέτρα. Furthermore, the grammatical structure employed in the line is more often used in Greek for contrast than for assignation. Thus, many have concluded that the word “rock” must refer to something other than Peter. That is, “ThouIreneus, the earliest known writer to argue that the Roman bishop should be the head of the Church, neglected this scripture. Surely it is no coincidence that the New Testament with which he was familiar was written in Greek.

Now consider this famous passage from Arthur Conan Doyle’s story, “Silver Blaze:”“Is there any point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

“To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

“The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

“That was the curious incident,” remarked Sherlock Holmes.

Holmes would likely be most troubled by the curious incident in the other three gospels. All three synoptic gospels (Mark, Matthew, and Luke) contain the context for the story of the keys of the kingdom. It begins with Jesus asking “Who do the people say that I am?” The three narratives are very similar, but only Matthew’s account mentions the church built on a rock, the keys of the kingdom, the gates of hell, and binding and loosing. Why did the other three evangelists emulate the dog in “Silver Blaze?”Of course, numerous episodes are mentioned in only one gospel; few events are described consistently in all four gospels. This lapse would therefore not bother the many Christians for whom one biblical reference suffices. But how could all but one version of the story miss the very basis of the Church’s structure? What could explain the fact that the other three gospels ignored[2] this crucial event?

Wise guys in Sr. Mary Immaculata’s class might have dared to suggest four possibilities:

1. The author of Matthew got it wrong.

2. Only Matthew had heard about it. Most biblical scholars, however, have determined that Luke was written after Matthew and that John was written much later.

3. The other three authors thought that it was unimportant. This fits with the most skeptical explanations of the issues of the translation.

4. The lines in Matthew were interpolated[3] later. When the provenance or authenticity of a particular verse of scripture is suspect, the Church’s fallback position is that even if the author of the verse is questionable, and even if it seems inconsistent with the surrounding text, its standing as divinely inspired scripture – as declared by the Council of Trent in 1546 and ratified by Pope Paul III – overrides any petty textual dispute. However, the very authority of the council and the pope to make that judgment is largely based on this pair of scriptural verses. The horse must precede the cart.

Not only do Matthew, Mark, and Luke agree on the prelude to these verses. Mark and Matthew also concur almost to the word on what happened next. All quote the words addressed by Jesus to Peter:Mark 8:33: “Get thee behind me, Satan: for thou savourest not the things that be of God, but the things that be of men.”

Matthew 16:23: “Get thee behind me, Satan: thou art an offence unto me: for thou savourest not the things that be of God, but those that be of men.”You can search St. Peter’s Basilica from the bottom of the deepest tomb to the cross atop the cupola and from the base of the steps to the enormous throne in the apse, but you won’t find any sign of these verses.

[1] Several versions of the text of verse 19 in Greek can be found at http://biblos.com/matthew/16-19.htm. The problematic phrases, έσται δεδεμένον and έσται λελυμένον (I could not figure out how to put the smooth breathing marks on the έ's), are in the future perfect tense, indicating that the heavenly action will precede the earthly “binding” or “loosing.” The verbs used for the latter are in the simple future.

[2] A modification of Matthew’s lines can be found in The Book of Mormon. Jesus says to his twelve Nephite disciples in 3 Nephi, 11:39: “Verily, verily, I say unto you, that this is my doctrine, and whoso buildeth upon this buildeth upon my rock, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against them.” This book was allegedly written in “reformed Egyptian” and translated into English by Joseph Smith in 1830 using a “scrying stone” in his hat.

[3] Actually the only student in S’ter’s class who might have used the word “interpolate” was the girl who read the dictionary, and she was much too respectful (or intimidated) to raise this issue.