Chapter 2: The Arrival of the Romei

Rome's air is deadly. Pope Benedict’s responsibilities required him to inhale far more of it than any man should. As often as possible the pontiff had retreated to the clean and refreshing clime of Tusculum and the hills, but his obligations to the Church and the people circumscribed his ability to schedule such holidays. He was therefore constantly subjected to illnesses and fevers endured in the city since the time of the Caesars. In March of 1024 the last of several affliction restricted his abilities to perform his duties. Concern for his health spread throughout the city, and rumors abounded. My father sensed the need for quick and decisive action. He and my brother led reserve forces down to the city to provide assurance that order was being enforced. On April 9, the Lord summoned his ever-faithful servant Benedict. No one doubted that my Uncle Romanus was the only suitable successor. He received the tiara in May.

My education was interrupted so that I could participate in the day-long investiture ceremonies for the new pontiff in St. Peter’s Basilica.[1] Although I appreciated that serving as an acolyte was a great honor, the rituals soon grew tiresome for a person of my age and demeanor. I was forced to don outfits that were ridiculed by my friends. I had no trouble with the Latin,[2] but, having stood at attention for a very long period in the stultifying atmosphere of the church, I must have dozed off for a short time. The brass thurible slipped from my hand and crashed noisily on the floor. The incense within spilled, and the charcoal was no longer usable. It was extremely embarrassing that a servant was dispatched to bring me a new piece of lit charcoal.

I felt great relief when Uncle Romanus finally completed all of the prescribed activities and was universally recognized[3] as Pope John XIX, Supreme Pontiff of all Christianity. The most dramatic moment occurred when Cardinal-Bishop Benedict Pontius reached beneath the sella stercoraria on which my uncle was seated. After fumbling around for a few heartbeats he cried out “Testiculos habet, et bene pendente.” After the new pope had been provided with the insignias of his office, the tiara was placed on his head. A queue of the faithful, headed by my father, then prostrated themselves before the Holy Father in order to kiss the cross sewn onto his right slipper. On the following day a long procession passed through Roman neighborhoods to provide the citizens with an opportunity to greet their new bishop and pontiff.

My father immediately assumed most civil responsibilities previously entrusted to Uncle Romanus. Haste was critical because the perfidious Crescentius family had maintained a presence in Rome throughout Benedict’s pontificate and was ever watchful for a chance to reassert itself. One of them had even seized the office of prefect for a short period. Therefore, during the inherently dangerous period of pontifical transition my father’s forces moved quickly to secure key areas of the city. They quickly snuffed a few minor incidents.

Around the middle of July Brother Alexius informed me that he and I would be spending more time in Rome over the next month or so on a special assignment for the Holy Father. My family greatly preferred the hills to the city, especially during the summer. Nevertheless, I was very excited to be chosen for a special project for the papacy. Brother Alexius explained that distinguished representatives from Emperor Basil and Patriarch Eustathius were sailing from Constantinople to pay their respects to the new pontiff. Alexius had been named official translator, and he had selected me as his scribe. What a thrill to be chosen over all his students and all the brothers at the monastery! I resolved to atone for my solecism during the papal investiture ceremony with a praiseworthy performance.

The imperial ship arrived in Centumcellae[4] on the last day of the month. As the dignitaries from Constantinople disembarked, the welcoming committee of Roman nobles assembled on the beach watched in awe. The Greeks' raiment was of the finest silk, linen, and cotton. Whereas even the noblest Romans wore plain garments except on rare ceremonial occasions, the clothes of the visitors were festooned with ornate designs and brocades. The delegation's ten members wore rings and baubles with precious stones that sparkled in the sunlight. Even their sandals were studded with jewels. Every movement exuded pomp, grace, and dignity. No Roman had ever beheld the like.

Accompanying the delegates were more than twice their number in slaves, distinguishable from the Greeks by their plain clothes and from one another by a wide variety of skin tones, facial features, and hair styles. They ported the visitors’ trunks, crates, and cartons down the ship’s gangplanks to the dock. Some Romans were shocked by this exhibition until they learned that most of the slaves were Mohammedans who had been captured in battle and had refused the option of conversion to the true faith. One of the most muscular was even a black-skinned Moor, the first of his race whom most of us had ever seen.

The delegation of Romei[5] consisted of two bishops, two military officers, and six government functionaries. One bishop and five of the laymen traveled with their wives. The youngest and sole female lay official was named Naomi. She served as scribe and translator.

I was surprised that both bishops fondly remembered Brother Alexius from his youth in Constantinople. My tutor also knew two lay delegates. He could not restrain himself from inquiring about people, places, and events in Constantinople. He took some time to renew relationships and establish new ones before undertaking the short journey to the city. To prevent interference from highwaymen a squadron of my father’s most proficient men-at-arms escorted the convoy.

That evening Pope John sponsored a banquet for the guests in the Lateran Palace. I was ordered to attend in order to assist with communication. Four guests spoke passable Latin, but often their thick accents impeded understanding. After paying the expected obeisances to the Holy Father, the Romei regaled us with tales of the glorious bygone days of the Empire, both when Rome had been its capital and in subsequent centuries. It soon became apparent, as Brother Alexius had previously intimated, that their knowledge of our city’s history exceeded ours. Our guests informed us that in the era of Saints Peter and Paul Rome boasted more than a million residents, and nearly every known tongue could be heard in the marketplaces. My father respectfully responded that he had great difficulty believing these claims. He estimated that the city's current population was perhaps twenty thousand. That fifty times that number ever resided there taxed the imagination. If true, ancient Rome must have been magnificent beyond description, as well as horribly crowded.

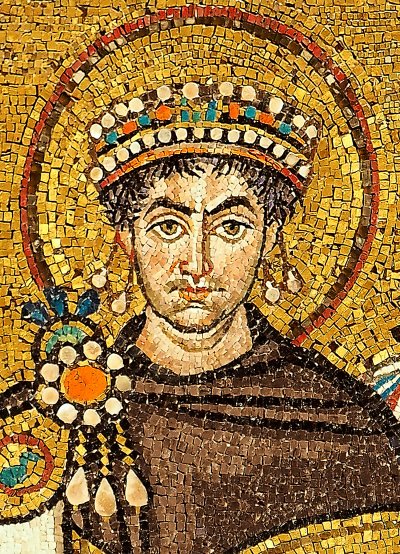

Cyprian, the more eloquent of the Greek bishops, must have detected a nugget of wisdom in my father’s remarks. He speculated that the Lord probably did not intend for excessively large numbers of Christians to congregate in one place. For example, at the summit of its glory Constantinople was stricken with a horrendous plague that struck down more than half of its inhabitants during the reign of the first Emperor Justinian.[6] “No one can claim perfect comprehension of God’s purpose. Still, perhaps the pestilence was the Lord’s sign that the faithful should abandon the serenity and familiarity of earthly comforts in the homeland in favor of spreading the message of the gospels to far-flung corners of creation.”

All present nodded in appreciation of the Greek priest’s erudite and cogent analysis. I wondered if anyone else noticed the irony. The speaker and his companions obviously possessed far more “earthly comforts” than any of us had imagined possible. Nevertheless, no one was so boorish as to mention this incongruity. I knew enough to keep silent. In fact, I recognized wisdom in the statement. In time it became a focus of my own life.

My father and brother offered to escort the guests on a hunt on the day following the Holy Father’s banquet, but the Greeks preferred to devote a few days to exploring the city. Apparently many of Rome’s ancient structures were well known in Constantinople, but few Romei had personally viewed them. Our guests showed more interest in the dilapidated remains of heathen buildings from imperial times than in the basilicas, shrines, and relics for which the city is famous. The visitors also announced that after inspecting ancient Roman architecture they would greatly appreciate some time in private consultation with the Holy Father about important religious matters. My father advised them that spending a few days in Rome would probably do no harm, but after that visit the entire party should definitely relocate to our family’s estate in Tusculum. No one breathed more of Rome’s deadly summer air than was absolutely necessary. Father also warned them to exercise caution in the Forum and its vicinity because Baldocax[7] had been the source of great consternation to that region all summer.

After two days of sight-seeing the Romei joined us in the great hall of my family’s palace for further discussions. The Holy Father was accompanied by Benedict Pontius, John Gratian, my father, and Alexius. I assumed my role of official amanuensis. In the first session Cyprian identified himself as the principal spokesman for both the patriarch and the emperor. He began by expressing sincere praise for Pope John, his predecessor, and his family. He then noted that loyal Christians of the eastern patriarchates had grown increasingly frustrated by the state into which the papacy had devolved since the time of Emperor Constantine the Great. In his opinion the distance between the two capitals was less decisive than the gap between the progressive and open-minded attitude prevalent in Constantinople and the deplorable decadence into which Rome, including the papacy, had descended. The easterners considered the pontiffs prior to Benedict VIII, with few exceptions indeed, incapable of expressing their ideas in a coherent fashion, unwilling to involve the Greeks at all, or completely oblivious of activity on the other side of the sea. Now that the factions that previously held sway had finally been suppressed, a propitious opportunity loomed for Old Rome and New Rome[8] to cooperate with the shared goal of promoting and strengthening Christianity. Citizens of Constantinople and its empire seemed excited about this possibility.

Cyprian delivered these thoughtful remarks in a Latin noteworthy for its flawless grammar and precise terminology. His accent was unusual, but his pronunciation was unexceptionable. Most Greek legates knew little or no Latin, but they were doubtless familiar with Cyprian's message. The slaves of the Romei exhibited little interest in the presentation. Their main job was to wield ornate fans to protect the Romei from the heat. Occasionally one filled a goblet, fetched a morsel, or removed refuse.

I soon began to appreciate the historical importance of this meeting. Brother Alexius had indicated to me that the Greeks had not dispatched such a legation to the Holy See in many years, and no one could even remember the last visit to Constantinople by any pontifical delegation. I therefore strove assiduously to ensure that the permanent record[9] of the exchanges was as accurate and complete as possible. Naomi was engaged in a similar undertaking.

Cyprian’s presentation was followed by a delicious luncheon in which I and my brother Gregory partook. The Holy Father invoked the Lord’s blessing on the food and the assembled diners and then proposed a toast to the health of our friends and brothers from the east. The guests were appropriately impressed with the feast, which consisted of boar, hare, lamb, and a delicious assortment of vegetables, breads, and fruit. Several Greeks voiced such outlandish praise for the quality of the wine that Brother Alexius struggled to translate their comments. Evidently the Latin vocabulary lacked the richness to express the nuances of their compliments.

The afternoon session featured a Greek scholar named Philo. In Constantinople he maintained the portion of the emperor’s extensive library dedicated to Church history. He emphasized his eagerness to augment that collection with copies of whatever documents and information that we could provide him. Philo read Latin reasonably well, but he was much more comfortable speaking in Greek. Bishop Cyprian translated his address for the Romans.

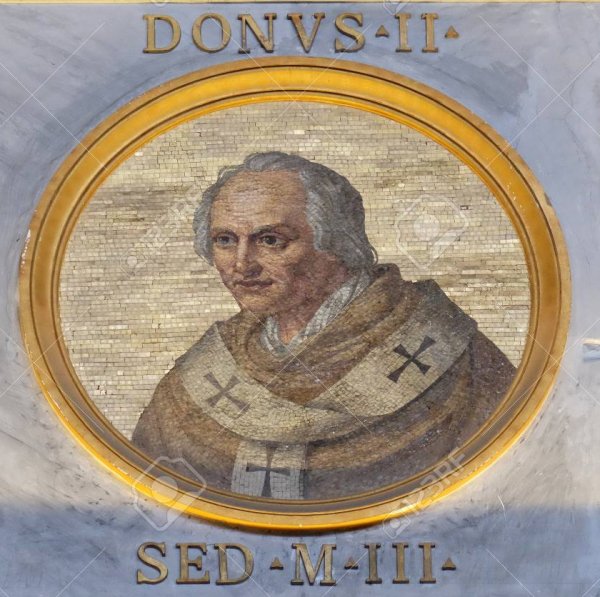

We showed Philo the Liber Pontificalis,[10] the official tome that contained short histories of each pontificate. As he pored over the text he often consulted his scrolls and asked detailed questions about twenty or so entries in the book. The references to the second Pope Donus,[11] who followed Pope Benedict VI, puzzled him. Donus's name was not in the emperor’s Diptych of the Supreme Pontiffs. Philo quizzed us about this pontificate, but no one could add to the few vague sentences that had been in the Liber. He was also surprised that Boniface VII[12] was missing from the book. Pope John admitted that, because of the many upheavals since the era in which the papacy dealt with the waves of barbarian invasions into the Italian peninsula, the diligence with which the Liber had been maintained was regrettably inconsistent. Some entries may have been composed years or even decades after the pontiffs had died. However, he pledged to improve the completeness and accuracy of the Holy See’s records.

Philo seemed bitterly disappointed with what we provided him. Benedict Pontius, who had long served the pontiffs as both librarian and chancellor, informed him that additional materials resided in his library in Porto.[13] He offered to introduce Philo to the Benedictine monks who oversaw the collection of papal manuscripts. This proposal suited everyone quite well. My colleagues were fascinated to discover that people who lived so distant from them exhibited such curiosity about Roman history. Few locals shared their zeal.

The following day was Sunday. After mass Philo, Naomi, Benedict Pontius, Alexius, three slaves, and I returned to Porto to visit the papal library. I learned that the Cardinal-Bishop of Porto had for decades or even centuries cataloged and preserved the papacy's documents. The collection largely consisted of pontiffs' letters to other bishops. Philo asked Naomi to copy portions of several selected volumes. Her ability to translate Latin immediately and effortlessly to flawless Greek astonished me. She seldom asked Brother Alexius about meaning or syntax. She wrote with her left hand, curving it around the quill so that she ended up pulling it rather than pushing it. Occasionally a whiff of some delightful fragrance escaped from her vicinity. The aroma puzzled and enticed me. Perhaps she employed unguents from some exotic region.

Philo paid special attention to all correspondence between the papacy and the Patriarch of Constantinople. The amount varied greatly from age to age; the three fools who preceded Pope Benedict VIII as pontiff completely neglected the responsibility of communicating with their counterparts in Constantinople. Philo’s interest was also piqued by ancient pontifical letters concerning a man named John the Faster. Philo stood close to Naomi and read over her shoulder. Occasionally he questioned her about a specific word or phrase. He asked her to make copies of these epistles, which were written by Pope Pelagius II[14] and Pope Gregory I, known as the Great. John had been the Patriarch of Constantinople in that era, and he had conducted a synod at his see. Both pontiffs objected strenuously to some terms used in the synod's report.

This subject failed to stimulate my adolescent mind at all. To be frank, I was far more intrigued by the graceful motions of Naomi’s left hand and the way that she cocked her head as she switched between Latin and Greek. Her age more than doubled mine, and she was no stunning beauty. Her features were regular enough, but her face was a little pock-marked, her nose seemed slightly too massive, and her hair was a bit too curly. As much as I essay to recall the color and shape of her eyes, I cannot visualize them. They always seemed buried in her work. What I remember most distinctly is the flow of her hands and her delicate and shapely wrists.

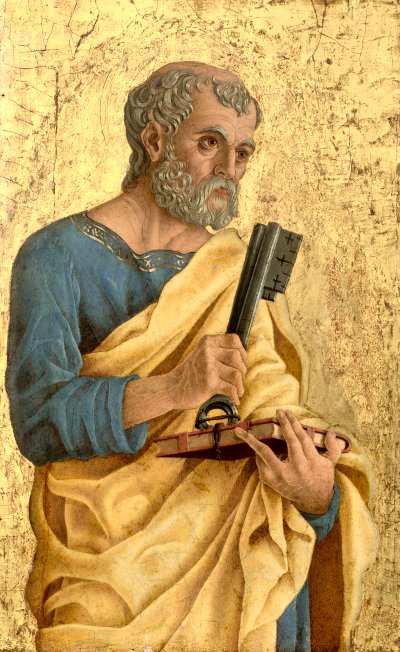

The next day’s discussion began with Bishop Cyprian’s respectful affirmation of the Holy See’s vital role in scriptural interpretation and governance of the Church. He emphasized that even during the periods in which the pontiffs had displayed base moral character, they continued to be guided by the Holy Spirit just as the apostles, sinners all, had received that Spirit at the Pentecost. He then painted a vivid verbal portrait of Christianity in the days of Saints Peter and Paul. Both men and many other apostles traveled throughout the Roman Empire establishing congregations, answering questions, and ordaining priests and bishops. The talk enabled us to experience in all of our senses the dynamic Christian enclaves of the first century in Ephesus, Antioch, and Macedonia. We joined St. Peter on his journey to Babylon and the famous council of apostles in Jerusalem. Every event and location was described with painstaking attention to detail. The Romans sat spellbound throughout. We had not encountered anyone so familiar with distant lands, and we had never heard such a brilliant elucidation of those events from nearly one thousand years earlier.

Occasionally the Holy Father interrupted the Greek bishop to request more information. His Holiness desired to know, for example, how it was possible for St. Peter to have been Bishop of Antioch and also the first Bishop of Rome. Did not canon law prohibit a bishop from moving to a different see? Cyprian admitted ignorance of the circumstances of Peter’s relocation, but he speculated that when Peter left Antioch for Rome, he assigned St. Evodius the job of overseeing his first diocese. The canon that prevents a bishop from abandoning one diocese in favor of another may have been instituted at a later date. He urged us to remember that canon law developed quite slowly. Furthermore, the written gospels were not even available to early Christians. Those first few decades were probably somewhat chaotic. Because the Church's written records were largely destroyed by the last pagan emperors, little is certain.

“What, then,” the pontiff asked, “occasioned St. Peter’s journey to Babylon?”[15] Again Cyprian professed his ignorance of what drove him to travel there, and he was likewise unaware of what transpired in Rome in his absence. He then used the question to emphasize an important point. The apostles could establish the Church throughout the civilized world precisely because of the stability that the Empire provided. The apostles Peter and Paul freely traveled throughout the Mediterranean and beyond. They could also send letters to distant congregations using reliable means of delivery. Because the Empire controlled both the sea and most adjacent land, disruption of communication was rare. As a result, a strong and cohesive Church developed throughout the lands under the Roman aegis. The pagan Empire was Christianity’s worst enemy during persecutions, but it also provided the structure and security necessary for the Church to thrive and expand in the eras in which the emperors were merely indifferent to Christianity.

Then he spoke admiringly of St. Constantine, the first Christian emperor. Under the influence of his holy mother, Helena,[16] he ended the ignominious persecutions perpetrated by his predecessors, established tranquility throughout the Empire, and allowed Christians to practice their faith openly. Truly his was one of the most remarkable ages of Christianity. Unfortunately, upon his death the Empire was rent in two, and ruthless barbarians soon made their noxious presence felt throughout the west. Within a few centuries the eastern Empire was assaulted by new enemies, the vicious Islamists and the hordes from the Far East.

In recent years the great Emperor Basil II had reasserted the preeminence of our common faith, learning, and culture. Cyprian enumerated his impressive accomplishments in solidifying and expanding the Empire and thereby Christianity. His successes had enabled clergy of the Patriarch of Constantinople both to expand the Church’s reach and to solidify the faith of loyal Christians in imperial territory.

The bishop then spoke in a soft but enthusiastic voice of the marvelous opportunity that presented itself. Strengthening bonds between the two great patriarchates would benefit Christians in both areas. Western Christians could gain more direct access to the Empire’s wealth and power. Eastern Christianity would profit from the improved relationship with the Holy See and the enhanced communication. The patriarch could more easily squelch outbreaks of heresy with the firm knowledge that Rome’s divinely inspired analysis of heretical claims would be forthcoming whenever needed.

Since the emperor and every loyal eastern Christian would value this sort of relationship, the party from Constantinople pronounced its willingness to recompense the papacy for the time and attention required to implement it. Therefore, the emperor had ordered that a considerable amount of treasure be loaded onto the ship that had transported them across the sea. Cyprian proposed that on the following day the parties return to the harbor to view the ship’s contents.

The Latin contingent buzzed with wonder and excitement.

Cyprian noted that one small acknowledgment would immeasurably strengthen the new partnership. Because the Saracens and barbarians still occasionally disrupted communication between the east and the west, the special relationship between the Holy Father in Rome and the Patriarch of Constantinople must be recognized and formulated. Cyprian proposed that the latter be allowed to distinguish himself from the other patriarchs[17] through use of the title “Οικουμενικός Πατριάρχης”

Although his oration's Latin was nearly perfect, the last two words were conspicuously pronounced in Greek. He apologized for this and explained that his command of the Latin tongue was inadequate for an appropriate translation. The Holy Father immediately turned to Alexius for an explanation of the term in plain Latin. The monk seemed reluctant to reply. He emphasized the needed to portray the term accurately. He asked for a little time to study the matter. He would then present a report for the pontiff and his advisers in private.

Pope John was taken aback by Alexius’s uncharacteristic recalcitrance. The pontiff had reasonably reckoned that all significant difficulties involved in the process of translating Greek to Latin and vice versa had long been resolved. After all, the two branches of the Church had used both languages for one thousand years. Furthermore, Alexius had never flinched from any assignment, whether mental, physical, or spiritual. The request to translate a two-word phrase seemed relatively straightforward. Cyprian, after all, was not demanding that the pontiff cede any powers. He only asked that the patriarch be allowed to add one more title to the long list that he already claimed. Pope John was a simple and practical man who placed little store by titles.

“I suspect,” Alexius began tentatively, “that His Excellency is correct in stating that there is no direct Latin equivalent for the phrase ‘Οικουμενικός Πατριάρχης.’ I am well acquainted with the basic meanings of both words. The second is, of course, familiar to us all: Patriarch. It is in no way controversial, at least not in regard to the Patriarch of Constantinople. The first word seems simple enough as well, but I am uncertain about its use in this context. The root word refers to an “inhabitant.” However, since everyone is an inhabitant of somewhere, more meaning must inhere in the term than a cursory inspection reveals. I surmise that it might be prudent to investigate whether this coupling of the two simple words has been employed before and, if so, in what context it was used. I should return to the library in Porto to determine whether it had previously surfaced in communications between the two patriarchates. As you know very well, Your Holiness, consistency is critically important in pronouncements issued by the Holy See.”

With those words Brother Alexius excused himself from the gathering and departed for Porto to research the documents. I expected him to ask me to assist him. Instead, he insisted that I join those scheduled to visit the ship on the following day. He wanted me to assess the precise value of the treasure there. Any small disappointment was more than offset by the exciting prospect of setting foot on the deck of a vessel that had actually sailed across the seas.

After a light breakfast we all climbed aboard carriages and rode down to the docks. This time our journey was interrupted by a band of rowdies who had positioned an enormous tree trunk across the road. My fathers’ men quickly answered the challenge, and the bandits, who had not expected such resistance, scattered in every direction. One young man was captured and taken to Rome for judgment. The crisis having been averted, I assisted the guards and slaves in moving the massive log to the side of the road so that wagons could pass. This innocuous incident visibly upset some of Romei. Evidently the roads on which they customarily traveled were less prone to such disruptions than ours.

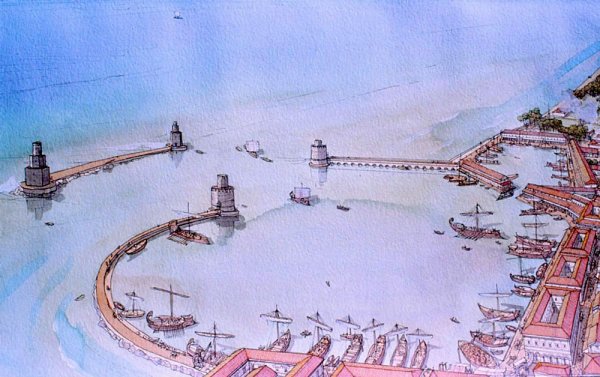

We arrived at the harbor and boarded the ship without further interruptions. For the first time I had an opportunity to inspect the vessel from onboard. My few sojourns in boats had done little to prepare me for the thrill of treading on the deck of a ship capable of sailing across seas. I was impressed by its carpentry, its intricate rigging, the cleverness of its appointments, and the precision required to fashion such a craft. The crew boasted that theirs was the swiftest and most elegant in the emperor’s fleet. Even so, the Venetians reportedly had dozens that could outsail it. In fact, when the emperor needed to enhance his fleet rapidly, he often rented ships and crew from Venice. I could happily have spent the entire day prying secrets from the mariners, but the other Romans were eager to inspect the precious cargo.

The sailors lit lanterns for us. We descended belowdecks where we beheld coffers brimming with gold and silver coins as well as chests of gems. I fastidiously recorded the quantities in each container, but my ancient brain no longer recalls the figures. Since at that point in my life I had no sense of the value of such items, the numbers meant little to me. I vividly recall the undisguised awe that registered on the faces of the Romans. Indeed, I worried that my godfather’s eye sockets might prove incapable of retaining his visual organs. He boldly reached into one chest of jewels and fingered its contents, and he held at least two of the gems up to the lantern's beams for closer inspection. The smile on his face was beyond a grin.

As eerie shadows from the lanterns played across his face, Bishop Cyprian addressed us with words to the following effect. The emperor had dispatched the negotiating party with these tokens of his appreciation of the accomplishments of Pope Benedict’s pontificate in restoring order to the western Church. Basil Bulgar-killer had complete confidence in the ability of Pope John and his associates to determine the best use for the voluntary donation that had been laid out before us. Inspired by the Holy Spirit, the pontiff was in the best position to determine what portion should be used to fund the missions, how much to distribute to the poor, and which dioceses most needed new churches. To prove his sincerity, the emperor had asked that the gift be considered anonymous and that the funds be added to the papal treasury without disclosing that fact to the public. The emperor felt that he had already been rewarded handsomely for his efforts to expand Christianity, and he harbored every hope of claiming in the hereafter his reward for this donation.

Cyprian again emphasized that the empire sought from Rome a simple pledge of renewed efforts to maintain and enhance lines of communication. In addition, he also humbly repeated the request that the Holy Father recognize the special role for the Patriarch of Constantinople in disseminating the Church’s sacred teaching in the regions not readily accessible to the pontiff and his liaisons.

Even before we returned to the deck, Pope John expressed his appreciation for the emperor’s generosity. The donation would doubtless help Holy Mother Church realize important projects that had previously been beyond the means of the Holy See. He considered it a sacred obligation to assuage the spiritual and material imperatives of the neediest western Christians. He also pledged to send letters and envoys to New Rome on a regular basis. The pontiff's encomiums to the emperor and the patriarch were replete with superlatives, but he cannily avoided any reference to the request for a new title for the latter until he consulted with Brother Alexius.

On Thursday morning, Brother Alexius, having spent two entire days reading books and letters in Porto, requested an audience with the pontiff and his advisers. I also attended, but in this case Alexius enjoined me not to bring my writing materials. He explained that at the conclusion of the meeting he would dictate to me what to record. The change in procedure surprised me, but I never questioned him. He then examined without comment the list that I had composed detailing the nature and value of the emperor’s donation.

When the papal delegation had assembled, Brother Alexius began by reading some letters that Pope Gregory I wrote concerning the use of the title “Universal Patriarch” by a Patriarch of Constantinople named John. Evidently the actual phrase in Greek had been “Οικουμενικός Πατριάρχης,” precisely the same phrase that was currently being proposed by the emperor's delegation. Pope Gregory had vehemently objected to the term. He claimed that no patriarch should be called “universal” because that would give the impression that the patriarch was not subject to the Holy See. Gregory was especially incensed that the Patriarch of Constantinople would make this claim because the designation of “patriarchate” was originally intended for dioceses that had been directly founded by the apostles, and Constantinople did not even exist until three centuries after the era of the apostles. In his opinion Constantinople was the least likely of all the patriarchates to be considered “universal.”[18]

This disclosure was met with shock and mumbling, but Alexius quickly squelched any hasty conclusions by providing more context. Pope Gregory’s well documented greatness[19] did not extend to linguistics. Knowing no Greek at all, he relied on a translation into Latin, and the unidentified translator had used the Latin word “universalis” to represent the Greek word “Οικουμενικός.” The problem, Alexius informed us, was that the Greek word was much more subtle than the Latin one. For one thing, the singular nature explicit in “uni,” the first two syllables of “universalis” was totally absent from the Greek phrase. Therefore, Pope Gregory’s argument that calling oneself “universal” put the claimant above the others was much more appropriate for the Latin version than the Greek.

“So,” the Holy Father asked, “what would be an appropriate translation?”

“Well, one candidate would be ‘imperiale,’ but that would not be precisely accurate either. Besides, there is a Greek word with almost the same denotation as ‘imperiale,’ and that word was not employed here. A better selection might be ‘people’s patriarch,’ because such a phrase could have quite different meanings depending on the context.”“Why would the emperor make this request?” asked my father.

“My experience and knowledge lie in dealing with words. The intentions of emperors are beyond my ken. Emperor Basil had a well-earned reputation as a very ambitious man. However, at this point in his life[20] who knows what might motivate him? I dare not speculate.”

Cardinal-Bishop Benedict Pontius could not comprehend the need for controversy. “Do I understand the situation correctly? The emperor is offering the Holy See a treasure almost beyond reckoning, and we are quibbling over one Greek word? Correct me if I am wrong, Brother Alexius, but are the Greeks not notoriously apt at twisting a word to mean whatever they want it to mean? We all know that the Lord gave the Keys to the Kingdom to Peter alone, and we likewise are certain that Emperor Constantine bestowed Rome and the western territories on Pope Sylvester I. What possible difference could adding another line to the list of appellations beneath the Patriarch of Constantinople’s signature make to us in Rome, the Patrimony, or, for that matter in the western Church?”

The pontiff nodded. He then turned to John Gratian and said, “We have not yet heard from you, Reverend Father. What do you think of the proposition?”

Gratian coughed twice before speaking, “I beg the indulgence of Your Holiness and this distinguished assemblage. All of you are so much more learned and eloquent than the Lord's most humble servant. Furthermore, my immortal soul’s wretched human vessel seems to have contracted a fever of some sort, and it has clouded my intellect. Following the discussion has been painful and exhausting for me. At my best, this type of argumentation would severely tax my meager faculties. I feel certain that the Holy Spirit will provide much better guidance than I could. I suggest that we should pray for His counsel now.”

Not waiting for a response, he immediately led a long prayer that was interrupted at least five times by coughing fits. He beseeched the Holy Spirit to intervene and assist the Holy Father in his assessment of the Greeks’ offer. This effectively put an end to the meeting.

The next morning we learned that John Gratian had sought the Holy Father’s permission to repair to Rome for treatment for his fever. Pope John, of course, consented. After bestowing his blessing on the archpriest, he expressed his fervent hope for a speedy recovery.

Fridays in Tusculum were always quite special. The flesh of animals was, of course, absent from our tables, but the cooks proved their ability to concoct delicious meals from the creatures that inhabited the lakes, the streams, and the sea. For us it was the best of both worlds. The absence of meat reminded us of the ultimate sacrifice that Jesus made for us sinners, and the sumptuous substitutes occasioned praise of the earth’s bounty.

Our agenda was also quite different. Cyprian, Naomi, Alexius, and I were sequestered in a room to compose a proposed letter from the Holy See to the emperor. The first draft was written by the Romei. Cyprian wanted to take as much time as necessary to ensure that the Holy Father felt comfortable with every aspect of its contents. The Greeks’ plan was for Pope John to sign the letter at the conclusion of our meeting. The delegation would then return to Constantinople to deliver it. Bishop Cyprian produced both Greek and Latin versions of the draft. In the Latin version the phrase “Οικουμενικός Πατριάρχης” remained in Greek.

Alexius made it clear that the pontiff had, at least to his knowledge, not as yet determined whether he would consent to the emperor’s proposal. His Holiness’s only firm decision was that, as always, he would follow the Holy Spirit’s guidance. He had secluded himself in the chapel in order to avail himself of it more readily. Even so, because the Holy Father lacked confidence in his own command of the Greek language, he had ordered Alexius and me to help produce a letter that expressed concurrence. If the pope decided against the plan of the Romei, the small amount of time that we had wasted on this undertaking would scarcely matter.

Alexius and Cyprian sat side by side and together read through the Greek text one phrase at a time. Across the table from them I sat beside Naomi. Whenever Alexius and Cyprian agreed upon a phrase, Naomi transcribed it. As she wrote, Alexius dictated the Latin version for me to record. Thus passed much of the day. Naomi and I mostly sat in silence while the two clergymen discussed textual nuances. We remained as motionless as possible to avoid distracting the them. Eventually I found myself gradually becoming enveloped in Naomi’s intoxicating scent. Only with the most determined effort was my mind capable of any task other than a futile attempt to isolate its components. When she recorded a sentence in Greek, I became enchanted by the rhythmic flow of her hand as it effortlessly shaped one perfect character after another.

More than once Alexius reproved me in order to force my attention back to the task at hand. I clinched my teeth and attempted to direct all my energy to the document before me, but it became more and more difficult. In the end I no longer could distinguish Alexius’s spoken words at all. They blended into a sort of rhythmic buzzing in the background that seemed only vaguely related to Naomi’s beautiful writing. As the buzzing grew louder in my head, I was shocked to see her set down her pen, place that beautiful left limb on my own scrawny right wrist, turn to me, and say, “Theophylact, is something wrong?”

Her innocent action produced startling effects. It shattered my reverie and impelled me to realize that Alexius must have been talking for some time. It also engendered a frightening condition in my gorzo that I had never experienced before. I hastily rearranged my garments to conceal it. No one mentioned it, but in such close quarters others must have noticed my condition. A wave of humiliation and dread engulfed me. I knew in my heart that I had once again failed my family, my tutor, and my Church. Thenceforward my mind insisted that my body do nothing but faithfully record the Latin version of the letter. I must report that these exertions achieved little. Alas, my carnal lust grew. Eventually Cyprian and Alexius were so exasperated with me that they agreed to adjourn for the day even though the letter remained unfinished.

On Saturday morning I, wallowing in shame and self-pity, refused to take breakfast with the others. I kept to myself until I spotted an opportunity to approach Brother Alexius. I asked him to walk with me because I needed advice. A few heartbeats occurred before he agreed.

Brother Alexius spared me the embarrassment of describing my problem. He explained that my aberrant behavior was probably attributable to Satan himself. “The members of your family—and you are most especially included in that number, Theophylact—have special obligations imposed by the Heavenly Father. Satan constantly strives to thwart the Divine Will, and in his arsenal are many powerful weapons. For the rest of your life you must anticipate his heinous influence during every waking moment and even on some occasions when you sleep.

“Yesterday’s incident indicates that the Prince of Darkness has already realized what an important assignment has been allotted to you, Theophylact. He has employed his powers to subvert your own heart and your own body in order to distract your mind and spirit from God’s purpose. These attacks will likely continue and even escalate. But take heart; the Lord has endowed you with everything needed to withstand all of Satan’s pernicious efforts. This I promise you, but your outstanding intellect must construct effective defenses. For the remainder of your time on this earth your mind must realize that at times it cannot trust your heart and your body. Each can be a portal to diabolical invasions.”

This revelation shocked and frightened me. I struggled to fashion a reply. “But yesterday I felt as if my mind had completely abandoned my body. If it is not even there, how can it control what my body is doing to me?”

Alexius assured me, “You misinterpreted the event. Your mind was still attached to your body, and it will remain there until the Lord summons your soul for judgment. Yesterday Satan erected barriers—think of them as invisible walls—within you to bar you from effectively employing your mental faculties when you needed them the most. He can be very clever. You must learn to make full use of your intellect while you still have control over it to devise counters to Satan’s machinations.”

“But how do I do that?”

“Your advantage is your comprehension of his mode of attack. When first you notice yourself losing control, try to circumvent the invisible wall by concentrating on something contrary to the fiend’s purpose. Consider what Jesus endured for us. Concentrate on His scourging at the pillar or Pilate washing his hands. Some men find that thinking about stern looks from their mother or their father helps address the problem. You might want to call to mind an image of the Holy Father himself, whom you have known all of your life, or the hegumen, an archetype of saintly behavior. The important thing is to plan ahead so that at the first sign of attack you can implement an effective strategy before the situation is beyond your control.

“I must reemphasize how important this is. You are engaged in a personal battle with the Prince of Darkness himself, and far more is at stake than your own immortal soul, as important as that is. God has devised a special plan for you, Theophylact, and you must listen for His calling and respond to it enthusiastically and effectively. To play your crucial part in God’s plan, you must have full control over your heart, mind, and body when God requires something of you.”

“You scare me, Brother Alexius. Why must I battle Satan all by myself? I am just a boy. I am no match for the devil. My brother berates me every day for my lack of skill in combat.

“What about an exorcism? Could not the Holy Father drive the devil from my body?”

“Exorcisms are useful for cases in which a demon has assumed control of someone’s mind and body. This is different. Satan is not a demon, and he controls neither your body nor your mind. It might seem like it, but he does not. Trust that the Lord will provide the strength and skill needed to win this battle. You only need to learn to marshal the resources that God, in his infinite wisdom, has provided you; I promise you. I have great confidence in your abilities, Theophylact.”

“Am I the only young person who is called to fight Satan?”

“By no means. Everyone must do battle with him or his minions, but most people are only fighting for their own immortal souls.”

“What about you? Have you had to fight him?” I asked.

“Indeed. My own battles commenced when I was about your age. I tried several methods to defeat him. In the end, the monastery became the key for me. I found that Satan’s power was diminished within its walls, and I drew strength and resolve from other monks. Although the battle has never ended, eventually I became familiar with his tactics, and I developed effective counters.”

“What are your counters? Can I use them?”

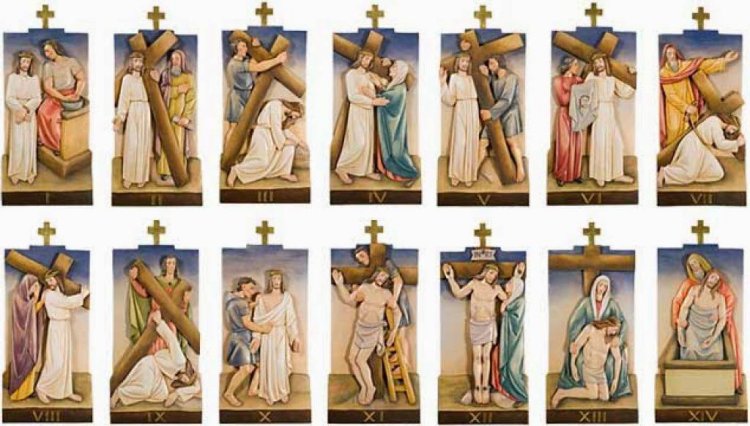

“Well, I suppose that you can try. They may not work as well for you. You may need to develop your own. Mine are based on Holy Scripture. I concentrate my thoughts and imagination on the passion of Christ. I involve each of my senses in intense concentration. To do so, I have memorized fourteen events in Christ’s final day. I imagine myself in each scene, and I conjure up every sight, sound, smell, taste, and tactile sensation that the Lord must have experienced on that awful day. If the Lord, after taking on human form with all of its shortcomings and weaknesses, could tolerate that treatment, then I should be able to deal with my petty annoyances.”

“What are the fourteen scenes?”

“You probably could name them if you thought about it. Here they are:

1. Jesus is condemned to death.2. Jesus is given His cross.

3. Jesus falls the first time.

4. Jesus meets His mother.

5. Simon of Cyrene carries the cross.

6. Veronica wipes the face of Jesus.

7. Jesus falls the second time.

8. Jesus meets the daughters of Jerusalem.

9. Jesus falls the third time.

10. Jesus is stripped of His garments.

11. Jesus is nailed to the cross.

12. Jesus dies on the cross.

13. Jesus's body is removed from the cross.

14. Jesus is laid in the tomb and covered in incense.[21]

My belief that the Lord willingly suffered and offered up His life for the salvation of all the faithful is firm. When I concentrate my thoughts on His story rather than my surroundings, I can generally regain control of my body and focus on my duty irrespective of the temptation.”

“I will try anything to eliminate this shameful behavior. I will memorize the scenes. If I sense that the devil is attacking me, I will parade them through my mind one by one. I certainly hope that it works.”

Brother Alexius reached into his habit and retrieved a very short length of thread. “Take this, Theophylact. It is from the cloth that Veronica used to wipe the face of Jesus. When under a diabolical attack, I have used it to concentrate my thoughts. A man my age probably needs it much less than you do. I hope and pray that it will serve you as well as it did me.”

I did not wait long for an opportunity to put this new plan into effect. That very afternoon Bishop Cyprian and Naomi joined Brother Alexius and me in the same room. Our goal was to finish composing the letter for Pope John, my uncle. This time Alexius sat on my side of the table, and Naomi was as far removed from me as was practical. I also noticed that her scent seemed different. She may have washed off whatever fragrance she had been wearing on the previous afternoon. My nostrils still detected the slightest essence, but it did not overwhelm me as before.

Cyprian and Alexius again quibbled at length over the text. It often took them a long time to agree on a single word. When they finally settled on the structure of a sentence, it was dictated first to Naomi in Greek and then to me in Latin. I steadfastly averted my eyes whenever Naomi wrote. Instead, I dedicated my mind to trying to compose my own translation while waiting for Alexius’s dictation. I gave thanks that Satan had apparently taken a holiday.

Then the Father of Lies struck from an unexpected direction. As she wrote, Naomi began to tap her foot lightly under the table out of my sight but within earshot. No one else seemed to notice it, but the sound tugged at my attention. I furtively glanced in her direction and realized that her writing was precisely matched to the beat laid out by her sandaled foot. It was so perfect, like Salome[22] dancing for Herod. I became transfixed again, and again my olfactory senses set to work devouring the nearly negligible aroma of her emanations. Before I knew what had happened, my gorzo again sprang to attention. When Alexius dictated the next phrase, I did not hear a word that he said.

“Theophylact!” he shouted in my ear.

I seized the microscopic fragment of my intellect that was still responsive and dutifully directed it to that first scene that I had memorized, “Jesus is condemned to death.” In my mind's eye there stood Jesus, tired, but handsome and defiant. Perspiration bathed his stern face. On the other side sat Pontius Pilate, a little confused and more than a little haughty, washing his hands of his involvement with such a silly case. And there was Naomi recording every word that either of them uttered, in Greek, of course. Only this version of Naomi was not tapping her foot. She danced lightly around the prefect’s chamber as she wrote in perfect cadence with the beat that emanated from her alter-ego’s foot. She whirled around with greater and greater abandon, her skirts lifting to her rounded knees, and her sleeves revealing those graceful arms. A loud smack on the side of my cheek dissolved the scene and knocked me to the floor.

“That is enough, Theophylact. I suggest that you retire to your room now.” I looked up at my tutor. He was rubbing his right hand with his left. He must have struck me so hard that he had injured himself. I literally crawled out of the room and hunkered down outside the door until my gorzo returned to normal. Once again I was suffused with humiliation, embarrassment, and fear. I drew the thread from my pocket, contemplated the Precious Blood, and fervently prayed that God would snatch me bodily at that moment, snuff out the light of my miserable existence, and designate someone else to play my “special role,” whatever it might be.

A little later my brother Gregory, who had just returned from drilling his troops, found me lying on the floor whimpering. He helped me up and asked me what my problem was. I refused to speak; it was just too shameful. He ordered me to accompany him out into the courtyard. We ambled together through the gate, so that we were outside the town walls. A short stroll brought us to a wooded area near a stream.

“Listen to me carefully, Theophylact. You will probably not understand completely what I am saying, but you must accept it as the truth. You are still just a youth, and an exceptionally ignorant one at that, but you must immediately learn something. Today. Now. This instant. You are a very important person, not a smart one, not a strong one, but a very special one. You must therefore act like an important person. If the public sees you as weak or infirm, disaster will ensue. I am serious. Disaster, nothing less. No one expects perfection, but you must always comport yourself so that you appear competent and in control. Do you understand that? Competent and in control.”

“No, I do not understand. Why am I so special? You are better at everything than I am. Why are you not special?”

He grabbed me by both shoulders and shook me hard. “I am also special, you still-born donkey. Have you noticed anyone else my age who was assigned command of the defenses of the entire city of Rome? But contemplate this: I am not as important as you are, and my job is much easier than yours is likely to be. Do not waste time trying to figure out why this is so. You will eventually come to understand it better. Until then you must accept it and live with it.

“Now tell me what your problem is. Maybe I can help.”

I told him about everything except the thread. He chuckled, but only for a few heartbeats.

“All right,” he said. “I suppose that this sort of experience is what older brothers are for. But what a moron you are! I cannot believe that you asked a monk for advice on sex. A monk! Oh, well, this only confirms that I accurately assessed your stupidity. Your knowledge is limited to what is in books.”

He punched my shoulder. He probably intended it to be brotherly, but Gregory was very strong and I was unprepared for the blow. It knocked me from the rock on which I sat. He quickly helped me up and delivered an impromptu lecture on the nature of the male anatomy and what I could expect. After that he gave me some advice. “Do not pay any attention to those monks. If they were not complete idiots about this subject, they would have never taken those vows. That silly plan of trying to summon up holy thoughts only works for people with a negligible amount of libido or an extraordinary amount of holiness. Believe me: for the men of our family it is worthless. And forget that nonsense about Satan, too. Even if Alexius is right, even if you are Satan’s primary target on this earth, it does you no good to fret about it. Instead, you need to learn to control your own body. When your gorzo perks up like that, it means that your balls are overloaded. Nothing more. It is shocking the first few times, but you soon get used to it. If you need to control your gorzo, you just need to learn how to keep your balls empty. Now stay right here. I will return with what you need.”

In his absence I weighed my brother’s words against those of my tutor. The two most important people in my life had offered contradictory advice, and I struggled to judge between them. Gregory soon brought me a small jar of a thick liquid. “This,” he said, “is mostly olive oil. It is completely harmless. Here is what you do. Go find a secluded spot in the woods and use this unction on your gorzo. Think about Naomi dancing before Pontius Pilate or something. You will soon figure the rest out. If not, try again later. If you still have a problem, which I seriously doubt, come see me again.”

Something obviously occurred to him. “By the way, did that monk give you some kind of relic or talisman to ward off the devil?” I sheepishly told him about the thread and showed it to him. He snickered in disgust and snatched it from me. “If this is a thousand years old, then I am a high priestess in the Church of Julius Caesar. You must be as gullible as the idiots who believe that some kind of holy magic inhabits those relics that the Church sells to pilgrims from distant lands. Take it from me, concentrating on blood and women’s clothes is not going to help anyone with your problem.

“I have an idea.” He turned around so that his actions were half-hidden from me. He plucked a hair from his beard and handed it to me.

“Please accept this hair that was shaved from the head of St. Ignatius of Constantinople.[23] Legends say that he was so saintly that no impure thought ever entered his mind, at least not after they gelded him. This incredibly valuable hair was awarded to our great-great-great-grandfather by the patriarch’s nephew for his heroic actions in saving Constantinople from a fire-breathing dragon. It might have been a basilisk. The relic is my most precious possession, but I freely offer it to you, my hapless brother, out of love and the deepest respect. Furthermore, I guarantee that it will work at least as well as the thread that that monk tore from his underwear.”

I knew of an old shed that no one had used for years. The forest had grown up around it, but I knew a path that approached it. I went there with my new ointment, and it took very little time to determine how to use it.

I admit that throughout my life I have often displayed disgraceful ignorance, but I was never quite the imbecile that my brother claimed. I discarded the hair that he had given me as I strolled back to the city gate.

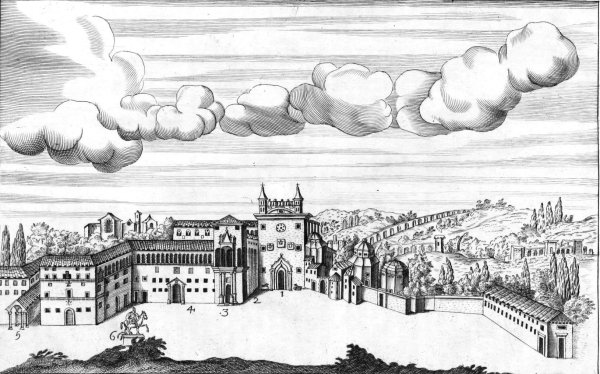

[1] The church to which he refers was replaced with the existing structure in the sixteenth century.

[2] The author was apparently more accustomed to the Greek rites.

[3] The processes used to select the pontiff have varied widely over the centuries. At various times voting was restricted to clergy and/or nobility. A few popes were just appointed by powerful emperors or kings. There is no record at all documenting the process used to select many pontiffs.

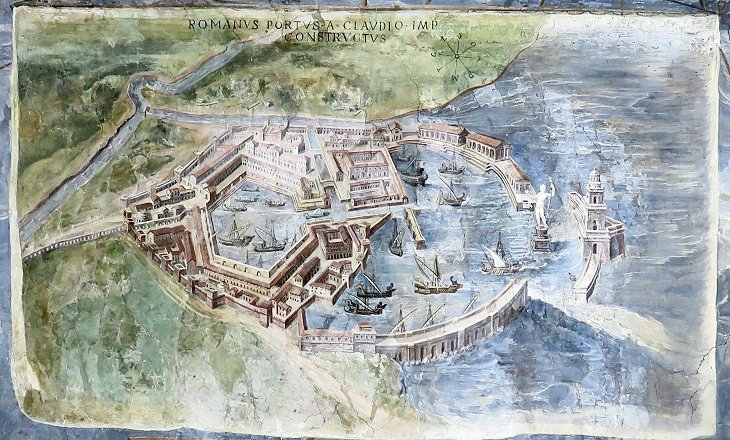

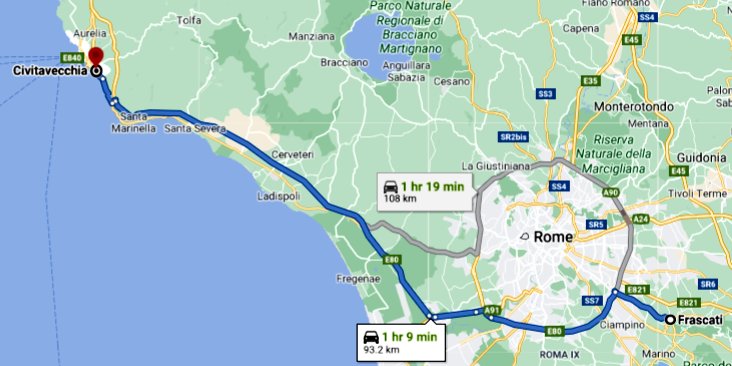

[4] Now known as Civitavecchia. Rome is not a port city. The Tiber River has never been navigable by large ships.

[5] In this period the Greek-speaking people of the Byzantine Empire used the term “Romei” to refer to themselves.

[6] 541-542 AD.

[7] This reference is puzzling. The context does not make it clear whether Baldocax was a person’s name. Other writers never mentioned him/it. It is even possible that the term refers to the popular name for some illness.

[8] The Byzantines often referred to themselves as “Romans.” They seemed to identify as much with the city that gave birth to their empire as with the land that gave birth to their language.

[9] If such a manuscript was produced, it was evidently lost or destroyed. The Vatican Library has been unable or possibly unwilling to verify its existence.

[10] The author does not use this name for the work, but in the context the reference seems clear.

[11] Donus II was removed from the official list in 1947.

[12] Boniface VII was elected pope in 974, but he was never approved by the Holy Roman Emperor. He is not on the official list. He spent several years in Constantinople.

[13] Porto (Portus in Latin), located at the mouth of the Tiber, was the major port for Rome until it silted up at some point during the Middle Ages. The city's bishop was for centuries one of the most important of the suburbicarians.

[14] This letter has been lost, but Gregory’s letter is extant. These two pontiffs served at the end of the sixth century.

[15] Many Roman Catholic apologists now aver that Peter’s mention of Babylon in 1 Peter 5:13 was a metaphorical reference to Rome. Even in Peter’s time the fabled city of Babylon had been deserted for two centuries. The upper Mesopotamian region that bore the same name, however, was still vibrant.

[16] Helena is considered a saint by both the Roman Catholic Church and the orthodox Churches.

[17] Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem had traditionally been patriarchates. Minor patriarchates had been established in Aquileia/Grado, Bulgaria, and Georgia.

[18] The Byzantines answered this charge by asserting that Constantinople was the direct successor of Christian outposts in Thrace established by the apostle Andrew, Peter’s brother.

[19] Not only is Gregory I considered a saint; he is one of only three popes called “the Great.”

[20] Emperor Basil II was sixty-six years old at the time. He died in the next year.

[21] These are, of course, the stations of the Via Dolorosa. If the document is legitimate, this is the earliest known formulation.

[22] The author called her “the daughter of Herodias”.

[23] Ignatius was Patriarch of Constantinople from July 4, 847, through October 23, 858, and again from November 23, 867 to October 23, 877. His father was Emperor Michael I Rangabe. Ignatius was forcibly castrated and tonsured at the age of 15 at the same time that his father was overthrown. He is considered a saint in the Roman Church but not the Greek Church.