Chapter 3: Education

After I began taking solitary strolls every dawn, midday, and dusk, I informed Brother Alexius that I was fortifying my defenses against the Prince of Lies by devoting more time to contemplating the wonders of God’s creation. My destination was usually the old shed. The results were immediate and remarkable. I successfully withstood Satan’s assaults during the rest of the conference. On the fourth such day Brother Alexius patted me on the shoulder and confided that he was very proud of my resourcefulness. He claimed that he knew that I had it in me. I refrained from replying that he had precisely identified my problem.

By the middle of the following week the two negotiating parties had finally reached concordance. Under cover of darkness the chests and crates were unloaded from the Greek ship and transported to the Lateran Palace. To ward against theft, His Holiness ordered the treasure divided into much smaller packets and secreted in secure locations throughout the city and in papal properties in Tusculum, Porto, Ostia, and Tivoli. My father argued that it would be much easier to protect the valuables if they were kept with the rest of the treasury in the heavily guarded chamber in the Lateran Palace, but the pontiff insisted on the dispersal. My father, of course, submitted to his older brother's judgment.

Pope John signed and sealed both the Latin and Greek versions of the pontifical letter that Cyprian and Alexius had composed. He entrusted the Greek version to Bishop Cyprian. All present expressed excitement over the progress that the group had achieved toward establishing a strong positive relationship to serve as a basis for spreading the Word of the Lord throughout Christianity’s two branches and beyond for years to come.

John Gratian rejoined the group on Tuesday. Everyone was delighted to hear that the intense prayers and the bleeding administered by his Jewish physician had effectively countered the base humors responsible for his fever. A slight cough lingered, and his complexion seemed a little ashen, but he assured us that the Lord had answered his prayers and given him the strength to resume participation. He led all assembled in an extended prayer of thanksgiving and praise.

During the following week a detailed presentation by a Greek general named Nicholas, translated by Bishop Cyprian, served as the focus of the discussion. Nicholas’s pattern of speech was very deliberate, but all present were touched by the deep emotion in his raspy voice. The political situation in southern Italy vexed the emperor, who was still vigorously engaged in spreading the Christian culture and religion among the Bulgars, an undertaking that required close attention. Unfortunately, the extensive imperial holdings in the southern part of the Italian peninsula[1] had recently come under pressure from many directions. For centuries the Romei had been forced to confront the Muslims in diverse regions of their empire. On most frontiers an uneasy peace prevailed. However, recent raids on Italian coastal areas by the Saracens from their base in Sicily had generated fear and anger throughout the south. Everyone recognized that my uncles and my grandfather had earned the respect and adulation of all Christendom by driving the Saracens from central Italy and Sardinia. That the infidels still menaced other nearby locations was valuable but extremely unwelcome news.

The general also voiced concern about transalpine peoples, whom he called “the barbarians.” They had elected Conrad as their king, and Emperor Basil anticipated that in time this upstart would lead his army to Italy and threaten both the papal and imperial territories.

In hushed tones he warned of a group of barbarians from northern Gaul, the Normans. They were so fierce that, by comparison, the Frankish and Germanic barbarians seemed as gentle as rabbits. In battle the Normans were famous for going berserk and fighting for days without surcease, completely free of fatigue and mindless of injury, no matter how severe.

Prior to the imperial party's visit, my geographical awareness had essentially been confined to the Alban hills, the road down to Rome, and a few churches and markets in the city. Our dealings with the Romei made me realize how distorted my concept of creation had been. I had always considered the pope the unchallenged leader of all Christians, and yet Emperor Basil and the Greeks had for decades actively served the Lord with no apparent papal direction. Tales of the Germans, the Franks, and others who dwelt beyond the mountains were rather commonplace among Roman officials and clergy. I had also learned from Brother Alexius about the Greeks in Constantinople. My knowledge of the Saracens, however, had previously been confined to the firm conviction that they were bloodthirsty heathen savages, no better than animals. The general’s speech was my first encounter with the Normans, the Bulgars, and several other nations. It dawned on me that the world might contain even more peoples, and some could field armies the likes of which might make even the great Caesars blanch.

Another notion disturbed me. Brother Alexius had taught that St. Constantine had granted Pope Sylvester I many lands mentioned by the general. I also knew that Charlemagne had reclaimed this patrimony for St. Peter over two hundred years ago. Basil was Constantine’s direct successor as emperor. Why then, I wondered, did his representatives seem to pay so little heed to the pope’s rights? He was, after all, the Vicar of Peter. Furthermore, why did Pope John fail to castigate them for this impertinence? As my understanding of the Christian world grew, my mind questioned the pontiff’s actual role in it.

Diverse aspects of General Nicholas’s presentation obviously fascinated both Pope John and my father. Both inquired about the likelihood of Saracen inroads on the peninsula, the precise location of their attempted incursions in the recent past, and the strengths and weaknesses of the enemy. The Holy See and the emperor agreed on the overriding imperative of preventing Islam from gaining a toehold on the mainland and the necessity of extirpating the Mohammedan heretics from their base in Sicily as soon as possible.

The Holy Father also expressed curiosity about the Normans' activities. The general portrayed them as a tribe of fearsome Norse warriors who had invaded Gaul and then settled there more than a century ago. They had subsequently converted from their pagan gods to Christianity. They had even abandoned their gruff native language in favor of the more civilized Frankish tongue. We learned from the general that a few decades earlier a group of Normans on their return from a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, had come ashore on the Italian mainland. There they had valiantly assisted the local citizenry in repulsing an attempt by the Saracens to exact their annual tribute. Impressed by the skill and courage in battle of the Norman visitors, the Italians had showered them with accolades and rewards. In the ensuing years Normans had continued to arrive, and they had become such a formidable force in Italy that Emperor Basil had grown alarmed.

This discussion was interrupted by the arrival of a breathless messenger. He reported that a group of monks associated with the Aventine monastery[2] had been declaiming on the streets and in the churches that Pope John had accepted a bribe from the Greeks in return for ceding to the Patriarch authority to make religious decisions for the eastern Church. The pontiff had allegedly accepted outlandish bribes and disavowed the wisdom of St. Gregory the Great. The monks asserted that there would essentially be one pope in Rome and another in Constantinople.

Romans were outraged by this. Many bore makeshift weaponry as they assembled in public squares. Pope John realized that the situation required immediate attention lest our enemies take advantage of the unrest to cause mischief. He ordered that the conference with the Romei be suspended for the nonce. He then met briefly in private with my brother and my father. Gregory was ordered to lead a sizable force to the city. He was under strict papal instructions to avoid inciting any violence. The goal was to exhibit a show of force to demonstrate order and control. My brother’s words, “competent and in control,” echoed in my ears. My father, Count Alberic, was charged with promulgating throughout the city the assurance that the monks were mistaken and that on the following day the pontiff would address this deplorable calumny. My father and brother immediately undertook their assignments.

After our evening meal Pope John explained to the Greek delegation that his enemies in Rome had been spreading rumors that he had betrayed the sacred obligation thrust upon him by Christ when he bequeathed to St. Peter the Keys to the Kingdom. Unfortunately in the near term the outraged Roman citizens would most likely assign to the Greeks a large measure of the blame for the blasphemous occurrence that had been alleged. The pontiff assured the Romei that he was quite capable of dealing this situation. However, while his people were so engaged it would be prudent for the visitors to repair to their ship and remain there for a few days. If an uncomfortable situation developed, the ship could easily weigh anchor and stay out of reach of the distraught Romans until order was fully restored.

Fervently wishing to avoid attracting more scrutiny, the delegation from Constantinople agreed to the pontiff’s plan. In order to avoid attention the Romei were asked to effect the journey down to the ship under cover of darkness in small groups. Each party would be accompanied by its own slaves as well as armed guards chosen from the Tusculan reserve forces. A few Greek delegates and their wives seemed quite upset at these developments; perhaps the inhabitants of New Rome showed more deference to their leaders than the Romans did.

As the Greeks hurriedly gathered together their belongings in preparation for the journey back to Centumcellae, I volunteered to serve as one of the guards. I argued that I was taller than most—even my brother!—and just as strong as many under my brother's command. I had received years of intense training from the most respected soldier in all Tusculum, my brother Gregory. However, I was informed that the Holy Father asked Brother Alexius and me to remain at hand in order to help him with the text of his address to the people of Rome. I felt bitter disappointment, especially when, in fact, His Holiness summoned neither Brother Alexius nor me that night.

The Romei began departing in groups for the harbor as soon as the stars became visible. Another group set out with the pontiff’s blessing after my brother Peter completed his task of counting to two thousand. This process continued until the entire delegation had departed.

At first light the Holy Father departed for the city in order to allay the citizens' concerns. Shortly after his departure the return of two Tusculan soldiers who had escorted one of the parties on the previous evening upset our entire household. All eyes were drawn to a blood-soaked sling on one guard’s right arm. The soldiers reported that the party that they escorted had been intercepted by brigands on the highway. Bishop Cyprian, two civilian officials and their wives, six slaves, and the two soldiers had comprised the fifth group to depart from Tusculum. As the carriages passed, bandits emerged from a nearby stand of trees. The Tusuculans and the slaves fought bravely, and they only surrendered after one guard had been wounded by an arrow to the shoulder. By then one of the Arab slaves had been slain by the bandits, and all present feared for their lives. The highwaymen searched the wagons, confiscated all the valuables, and hastily departed. We were all relieved to learn that the three Romei in their group had escaped injury. The other parties had reached the ship without incident.

Later we learned that the stolen items included a locked case belonging to Bishop Cyprian. That case contained the Greek copy of the letter that Alexius and the bishop had composed, and the pontiff had signed and sealed. I recognized an opportunity to contribute and rushed to Brother Alexius. “Should I begin translating our Latin copy of the letter so that the pontiff can provide the Romei with a new Greek version?” I asked enthusiastically. “If I start now, I think that I could finish before the midday meal.”

Brother Alexius urged calm. “We must never presume to anticipate His Holiness’s wishes. Remember that only the Vicar of Christ has been blessed with the unerring guidance of the Holy Spirit. Besides, the most likely outcome of this misadventure is that our men will quickly find the thieves and recover all the stolen items. Perhaps the malefactors will simply cast the case aside when they discover that it contains no valuable coins or jewelry.”

However, despite the best efforts of my brother's men, the bandits were never captured, nor the letter recovered. By morning an angry mob of Roman citizens had gathered at the harbor. Speaker after speaker denounced the Romei and urged swift and decisive action against both them and Pope John. When someone in the crowd produced torches and threatened to set fire to the Greek ship, the captain hastily set sail. The vessel tarried just outside of the harbor for a few days, but one morning it disappeared, and we never saw it again.

After the church bells had tolled for the Angelus on the day following the robbery, Pope John addressed a large crowd gathered in Lateran Palace's piazza. He spoke as a friend and fellow Roman citizen. He acknowledged the discussions with the Romei. In fact, he was delighted to report that the meetings had gone very well. The Greeks had, as a matter of course, brought donations for St. Peter, and he had gladly accepted them. He assured everyone that even as he spoke, alms were being dispensed in poor neighborhoods of the city. He scoffed at the preposterous notion that he would consider the sale of sacred privileges to the Greeks. He swore on the gospels that he would never relinquish any of the rights and powers of the Holy See to anyone. Pointing to the tiara on his head, he assured those in attendance that no one but the Bishop of Rome would ever wear it, and no one else could ever be the Vicar of Christ.

He then disclosed that the discussions with the emperor’s delegation had focused on how the two branches of the Christian Church could most profitably exchange information and join forces to eliminate the pernicious Arabic influence on the peninsula and in Sicily. The danger of strategic information being transmitted to the Saracens justified absolute secrecy. The talks had concluded successfully, and the Romei had departed. The pontiff was shocked and angered at those who had spread slanderous misinformation about the nature of the Greeks' visit.

Most listeners appreciated these words and returned home mollified if not convinced. A few monks still railed against the Greek influence, but the Holy Father’s announcement of the foreigners' departure removed the urgency from their pleadings, and the distribution of considerable sums to the poor buttressed the pontiff’s arguments. Rumors of Pope John’s intentions lingered, but the immediate crisis had been averted. It became apparent that the papacy remained a distinctly Roman institution. Neither the Greeks nor the monks had changed that.

At the time my thoughts focused on the small role that I had played. I was thrilled by the excitement and disappointed that I had could not use my years of combat training to help guard the bishop’s party. The battle seemed to have been close. Who knows? My sword might have been all that was needed tot turned the tide. I imagined myself feted in the city and proclaimed a hero by Romans and Greeks alike. That would surely have impressed Naomi.

Pope John never ordered Brother Alexius to produce another Greek copy of the letter. Moreover, I was not asked to assemble the extensive notes that I had made during the meetings with the Romei. As far as I knew the papyri remained in the small room in which we had drawn up the pontifical letter and were delivered neither to the pontiff nor to the library in Porto. Brother Alexius sternly admonished me never to discuss with outsiders my role in the negotiations. Such secrecy was, of course, the established protocol in such matters.

Subsequently other concerns suppressed consideration of the visit from the Romei. Not until my sixteenth or seventeenth summer did I undertake to review my notes to enhance my memory of the historic event. I searched our entire villa, but I could not locate the notes. I asked my mother about them. She said that about a month after the Greeks' departure one of the Holy Father's aides had removed the papyri for safekeeping in his personal collection at the Lateran.

I never questioned my mother's word on any matter large or small, but the notion of Pope John seizing my notes was suspicious. One aspect of the story particularly bothered me. The Cluniac monks who descended on the city had apparently learned not just of the Greek presence in Rome but also several details of the discussions. Who had informed them, and why? I could think of only one person who could do so, my own godfather, John Gratian. He was present when Bishop Cyprian outlined the request, and his subsequent consultation with his physician in Rome afforded him the opportunity to send a message to Cluny or to an affiliated monastery. No one else had left Tusculum during that period, and no message could be dispatched from the walled city of Tusculum without my father’s explicit approval.

By the time that I spoke with my mother, my brother was residing in his newly constructed palace in Tusculum. I sent a message to him asking for a meeting. Upon my arrival at his palace he poured us each a goblet of honey-flavored wine and asked me what was on my mind. I outlined my suspicions concerning John Gratian’s role so many years earlier.

“Holy mackerel!”[3] he exclaimed. “Are you saying that it took you years to figure that out? How does someone of your mental capacity even remember to place your sandals on your feet in the morning instead of on your ears? Wait; I know. You probably neglect to remove them before you go to bed.”

I ignored this unimaginative insult and persisted. “Well, then, if everyone else knew that Cardinal-Priest John had betrayed the Holy Father’s confidences, why was he not summoned before the magistrate or the papal courts and punished? Even if Pope John had been swayed by the Holy Spirit's divine mercy, why did no other members of the curia act to enforce justice? And what about you? You were in charge of the defense forces; why did you not apprehend him and bring charges against him?”

My brother grinned. “What would that have accomplished? Nothing. It would have merely provided ammunition to those damnable Cluniacs trying to subvert out the pontiff’s purposes.

“Could things have possibly ended better? The Romei received the blame for everything, and that Greek ship sat much higher in the water when it departed than when it landed. We not only obtained a wealth of information from the visitors; we also replenished the treasury at a very opportune time. Moreover, Pope John’s prompt and decisive resolution of the crisis elevated his standing among the faithful to a remarkable extent.

“One more thing: That despicable idiot Gratian was exposed to everyone who mattered as a traitor and spy. That was potentially a very useful development. Perhaps the pontiff will see fit to take advantage of it some day.”

“But,” I objected, “we never were able to realize the chance to cement the relationship between the eastern Church and Rome. Was that not the primary objective of the meeting?”

“It might have been someone’s objective, but I seriously doubt that it was very high on the emperor’s list, and Pope John surely never took seriously the possibility of extensive cooperation with those double-dealing Greeks. Everyone who counseled the Holy Father was aware that the Patriarch of Constantinople had always served at the emperor’s pleasure. Had Pope John given the impression that the emperor’s clerical puppet could enact important judgments on matters of faith and morals for the eastern Christians, there would soon have been two Churches, not one. Also, as became clear during that near riot at the harbor, the pontiff’s authority over the western Church would be subverted. The guiding principle of our Church has always been that only one man bears the Keys to the Kingdom, and that man is, was, and always will be the Bishop of Rome. From the day that the electors lay the tiara on his head until the burial detail removes it from his corpse, he alone has that authority.”

But what became of the letter? We all saw the pope sign and affix his seal to it.”

“What letter? I have no idea what you are talking about.”

“The letter that Bishop Cyprian and Brother Alexius composed. Naomi wrote out the Greek version, and I transcribed it into Latin. We worked on it for days. Surely you remember that. You even talked with me when I embarrassed myself during several of those sessions.”

“You must be hallucinating. It sometimes happens. The heat can send the mind reeling, or maybe you have contracted a fever from the miasma. Did you bring that letter with you?”

“You know very well that the Greek version was stolen by robbers in the middle of the night and never recovered. Mother just informed me that the Latin copy was taken by men representing the Holy Father for safekeeping in his library.”

“I was in charge of security that night. Some outlaws laid a trap on the road and robbed one of the groups, as you say, but only coins and jewelry were taken. The thieves were never apprehended, but the valuables were found and returned to the Greeks before they departed. No letter was involved, or at least no one told me about a letter. Furthermore, the papacy has never maintained a library in the Lateran Palace; the papal library has been in Porto for centuries. Ergo, no one seized the notes on the pope's behalf. The evidence is clear and overwhelming. There never was a letter. Perhaps you dreamt about it, and over the years the memory of the dream somehow became real to you. Have I penetrated through that thick marble skull of yours, or do I need to sharpen my chisel?”

I muttered that I understood, but I was lying. A grin appeared on his face that indicated that he had just bested me in some sort of competition.

A few years later, however, I recalled this exchange with more respect for my brother’s explanations. It seemed ludicrous for the Romei to imagine that they could hoodwink crafty men like my father, my uncle, and my brother with such a transparent proposition. Did they forget that they were no longer dealing with those Sabine idiots? I smiled as I wondered how they explained to the emperor the depletion of the ship’s cargo.

* * *

In the autumn of the year of Pope John’s investiture[4] my father hosted a banquet in our ancestral home in Tusculum. Joining our family members were important civil and religious officials. It was certainly the largest gathering ever held in our residence. I sat at a table with my mother and two younger brothers, Peter and Octavian. Gregory joined my father at the head table. Also seated there were the Holy Father, my aunt Theodora[5] and her husband Pandulf Duke of Salerno, three or four cardinal-priests or cardinal-bishops, and a gentleman whom I did not know. At the end of the banquet my father called for everyone’s attention. He introduced the stranger as another Pandulf, the Prince of Benevento. The prince then made the shocking announcement that his niece Costanza was to be married to my brother Gregory in the spring.

Costanza was escorted into the room to stand arm and arm with Gregory. She was absolutely stunning. Her lovely face seemed ablaze with hair that swept this way and that. Her sparkling gray-green eyes perched like colorful songbirds over either side of her upturned nose. Romans commonly have prominent aquiline noses. Hers was petite, and it constantly appeared to be asking a question. She clutched Gregory’s arm as if she were sinking in mire, and that limb was her only hope of rescue.

Is a smile a feature? If so, I should have mentioned it first. Hers was brilliant and toothsome. Every facet of her appearance radiated warmth and happiness; even her freckles seemed to glow. Gregory, too, was smiling, although he seemed not to know what to do with his feet. He continually shifted his weight from one to the other. I considered the possibility that the hold that Costanza had applied to his muscular arm was the only one for which he had never developed a counter. I choked back a laugh at his evident discomfiture.

My father proudly announced that a team of laborers would be constructing a suitable home for the couple on the grounds of the family estate. Father promised that it would be the envy of all the papal territories. He expected it to surpass even our family’s villa in size because it would serve in the future as a dwelling for a bevy of grandchildren. Everyone cheered wildly, and we drank toast after toast to the couple and their palace.

My father was true to his word. Within a week a train of wagons containing building materials began ascending the hill towards Tusculum, and a small army of workers arrived at the site. The few whom I recognized were Romans, not Tusculans. Before a month had passed the structure began to take shape.

The nuptials occurred in May. The Holy Father performed the ceremony before a very large crowd in Tusculum's cathedral. Everyone then adjourned to my parents’ home to enjoy a banquet that was even more sumptuous than the one at the betrothal. Even though large portions of the palace remained unfinished, the newlyweds immediately moved into their new home.

* * *

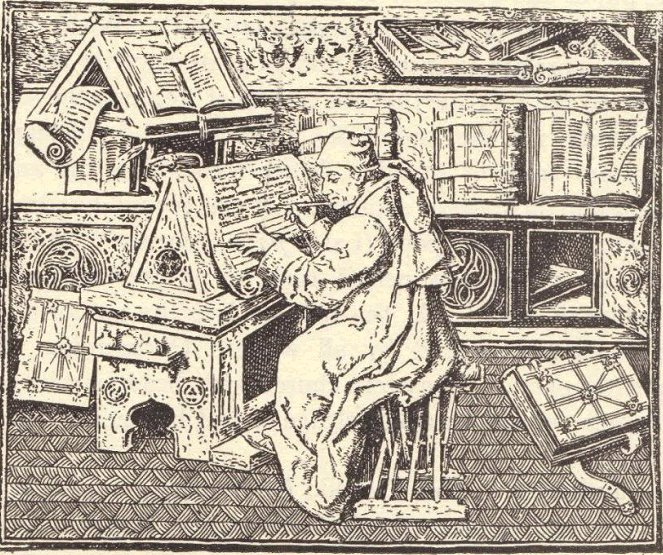

After the conference with the Romei the nature of my education changed dramatically. To everyone’s surprise Brother Alexius took a vow of silence and withdrew to a small monastery in the Abruzzi mountains. My relationship with my new tutor, Brother Clement, began poorly. Hoping to motivate me to greater diligence in my studies, he indicated that his goal was to keep me from ending up like my brother mindless sword-wielder used by others more clever and less scrupulous. I found his assessment offensive, and I firmly expressed that opinion. I insisted that I aspired to emulate my brother, the most admired young man not just in Tusculum but in all of the Petrine Patrimony. Nevertheless, I devoted myself to my lessons, and soon Brother Clement and I developed a satisfying and productive rapport. We concentrated on the subject matter of our lessons and never again discussed Gregory or my family.

Clement considered me ready to supplement my knowledge of the fundamental Christian texts with diverse materials, starting with the epic poems of Homer. I can still remember the astonishment I felt as his cavernous voice intoned the opening lines of the Iliad:

μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆοςοὐλομένην, ἣ μυρί' Ἀχαιοῖς ἄλγε' ἔθηκε,

πολλὰς δ' ἰφθίμους ψυχὰς Ἄϊδι προί̈αψεν

ἡρώων, αὐτοὺς δὲ ἑλώρια τεῦχε κύνεσσιν

οἰωνοῖσί τε πᾶσι, Διὸς δ' ἐτελείετο βουλή,

ἐξ οὗ δὴ τὰ πρῶτα διαστήτην ἐρίσαντε

Ἀτρεί̈δης τε ἄναξ ἀνδρῶν καὶ δῖος Ἀχιλλεύς.

I cannot overstate the power of the reaction in my mind, heart, and soul. Brother Clement’s sonorous recitation of the epic story of Achilles, Hector, and the others was by far the most inspiring thing that I had experienced in my young life. It surpassed all previous lessons. The contrast was not just the distinction between the biblical prose and Homer’s poetry. This was real music, not just an agglomeration of words. Several stories in the Bible were rather interesting, but the Iliad fascinated me from the first word to the last. The letters from St. Paul to early Christians focused on concepts that seldom resonated with my life in Tusculum. The tales of the Israelites could have been about people living on the moon. In contrast, reliving the exploits of heroic warriors engaged in a decade-long struggle with valiant adversaries appealed to my innate love of adventure. I learned how heroes could outwit gods and overcome monsters, and, to my shock and horror, how they could be humiliated and defeated by unarmed women.

I pondered that troublesome word “θεὰ” in the very first line. I was probably as well acquainted with the baffling concept of the Trinity as anyone my age, but I could not understand how could God, even with three persons, possibly be addressed as a woman. Brother Clement explained that the ancient Greeks did not believe in one God in the way that the Israelites, the Christians, and even the Saracens did. Like the Romans of old, they recognized a panoply of gods and goddesses. Each was associated with an aspect of creation. Poseidon ruled the sea, Apollo the sun, Zeus Cloudgatherer the weather, and so on. This notion seemed preposterous to me. How could there be more than one god? Unless they all just simultaneously popped up out of the void, one of them must have created the others. That one must the real God; the others were just powerful creatures. Maybe they had more powers than humans, but they were nothing like God. So, one day I asked Brother Clement which god had created the others.

He explained it to me in this fashion. “It is not useful to compare the works of Homer with the Bible. Creation, as you well know, is the subject of the first chapter of Genesis. The first chapter of the Iliad, on the other hand, portrays Achilles sulking on the plains outside of the walled city of Troy. This episode is set long after the creation of the world, and the Odyssey is even later. We have no indication of Homer’s notion of creation. Did he even think about it? If he did, how he reconciled the act of creation with the prevalent notions about the abilities and limitations of the gods has long since been lost.

“The multiplicity of gods, by the way, is the rule, not the exception, in the world. You probably have heard that in ancient times the emperors as well as the vast majority of Romans believed in many gods. Some haughty emperors even had the audacity to proclaim themselves gods! Before they converted to Christianity, the barbarians who live beyond the mountains also worshiped many gods. In some areas they probably still do.

“The concept of ‘god’ for all these people is substantially different from the God of the Bible. In their minds no god was omnipotent or omniscient. To the ancient Greeks and Romans a god was a prepotent being who exerted a great deal of influence on man's activities. When the ancients did not comprehend something, they often attributed it to a god. Their gods helped some people and plotted ruthlessly against others. Athena, for example, was the patron of the Achaeans, but some of them were also favored by other gods. Some gods apparently detested particular humans, or at least the human characters in the stories that have been handed down to us. The two things that all of the gods, even God as portrayed in the Old Testament, demanded were worship and sacrifice. Humans from Cain to Odysseus often paid the price for faulty rituals.

“Try to keep this in mind when we read Homer. Do not focus too much on the gods. Consider them Homer’s way of facilitating the narrative of the human adventure. If Homer's use of the same word “θεός” that St. Paul and the Romei use for the Lord God Almighty bothers you—and it definitely should—think of it in Homer’s work as a separate word that happens to contain the same four letters. Pronounce it a little differently if that helps. Concentrate on the plots involving the heroic Greeks and Trojans and their problems during and after their long and bloody war. When gods and goddesses listen to the poem, they can concentrate on the divine element. We who are not allowed on Mount Olympus should concern ourselves with humans.”

I laughed at his joke and eagerly accepted his advice. Whenever I saw “θεός” in Homer’s works I pronounced it as “τεός.” I was satisfied with Brother Clement's explanation, but I needed to pose one more question. “How did Homer know what the gods were scheming on Mount Olympus?”

Brother Clement looked at me quizzically. “Do you appreciate that Homer’s gods did not actually exist? Mt. Olympus might exists; I have never been there. The gods, however, did not. Homer inserted them into his story to explain the actions of the heroes in terms that his audience could understand. His listeners had heard many stories that involved these gods. So, they already had pretty well-formed ideas about what powers they had and what angered them.”

I was astounded by what I was hearing. “They did not exist? But they are right there on the page in front of us. How did they get there?”

My tutor favored me with his gap-toothed grin. “Homer probably never wrote anything down. He recited his poems from memory. The literal answer to your question is therefore that some monk probably placed them on the pages that you see. The answer that you are actually seeking is that the gods lived only in Homer’s mind and perhaps in the minds of his audiences. He created fables about them or recounted fables that others had invented in order to make the story about the human characters more readily appreciated by his listeners.”

“So Homer lied? Bearing false witness violates a stricture of the Decalogue. I have never seen my mother as upset at me as when she reproved me for telling a lie about my brother Peter. Is it sinful for Christians to read the lies that Homer wrote?”

“Your mother …” He abruptly diverted his discourse to another thought entirely. “A poem by Homer is no lie. It is a story. Reading or listening to stories is never a sin. Everyone appreciates that these works are not a history of the time. They are fiction.

“Besides, it is the liar, not the listener, who sins. If I told you that Poseidon was angry at you, that would be a lie. When Homer describes Poseidon's ire at Odysseus, it is just part of his story. Rest assured that it is in no way sinful for you or any other Christian to read it. As to whether Homer sinned, … Remember two more things. In the first place Homer had no knowledge of the commandments that God gave to Moses, and in the second place, the Savior has clearly instructed us all, ‘Judge not lest you be judged.’”

I was just a callow youth, and this revelation struck me with as much force as the most severe blow that my brother ever delivered in my martial training. The idea that anyone would take the time and incur the expense of writing down on papyrus or parchment something that he knew was not true was totally alien to me. Almost every manuscript that I had read was official Church doctrine, the Word of God. I had naturally come to conflate the written word with absolute truth. Later, of course, I realized that no more effort is required in writing lies, or what Brother Clement described as “fiction,” than in declaiming the truth. In fact, the primary purpose of this work is to refute the odious “fictions” written and spoken by others about my own life.

Under Brother Clement’s tutelage I joyfully immersed my imagination in the world of the two Ajaxes, Odysseus, Menelaus, Agamemnon, and the moody Achilles. I was especially taken with Diomedes, a mere human who actually seemed capable of getting the best of Poseidon Earthshaker. The Trojan Hector had proven himself capable of holding off all of the Greeks nearly by himself, all, that is, except Achilles. Then there was Paris, the rascal who started it all and eventually slew the mighty Achilles. Was he a clever hero or a despicable coward?

After the Iliad came the Odyssey, which I enjoyed even more. I could more easily identify with Odysseus than Achilles. Achilles reminded me of my brother, good at everything. Odysseus was talented, too, but his abilities were sometimes less obvious. For ten long years he sailed the same waters that the Romei had traversed. He used his cleverness as much as his strength and indomitable courage to overcome all obstacles. I longed for the chance to be among his brawny followers sitting in order beating the sea white with their oars when the early-born rosy-fingered Dawn finally appeared on the eastern horizon, and the sturdy vessel beneath them parted the waves toward the next adventure. I also spent much pleasurable time imagining myself as the leader of a crew of stalwart mariners.

Odysseus finally overcame all adversities, the most dangerous of which always seemed to be female. He returned to his native Ithaca and found his palace full of suitors for his faithful wife. I understood enough about married life to appreciate how intolerable such a situation would be for a man. He must have been transformed into a semblance of a Norman Berserker when he slew them all with his mighty bow. Blood flowed through the palace, the foul essence of the blackguards who dared to cuckold their heroic king. For some reason I never asked Brother Clement about the sinfulness of this vengeful act or any of the heroes' other undertakings that clearly seemed to violate the laws of Moses and the Sermon on the Mount.

When we had finished reading the Odyssey, Brother Clement informed me that we had exhausted Homer's works. I asked him if he knew of any other similar poems by other authors. He told me of the Aeneid, which was written much later in Latin. Most people, he told me, did not think that it quite measured up to Homer’s standard. So, I asked him if we could read the Iliad and the Odyssey again. He consented. He probably enjoyed it as much as I did. On the second pass he emphasized the poetic elements of the work: the meter, the metaphors, the puns, and the musicality of the composition. I enjoyed the tales even more the second time.

My introduction to these books brought me to a level of spiritual ecstasy that I had never before experienced. I simply could not get my fill of them. No student ever devoured the subject matter more rapaciously than I did. An unfortunate consequence was that compared with the non-stop action on the plains surrounding Troy and on the open sea, my life in the Alban Hills, began to seem dreadfully jejune.

* * *

During my fifteenth year my horizons again broadened. Brother Clement persuaded my father to enroll me in a school located in the Lateran. The students there were instructed by Fr. Lawrence,[6] a protégé of the brilliant Pope Sylvester II.[7] The priest was an imposing figure. His hair and beard were thick with coarse black filaments, each of which seemed blessed with free will that it exercised independent of its cohorts. His eyebrows were nearly as long as his beard, and they formed a sort of half-drawn curtain for a pair of dark deep-set eyes. His black cassock was always stained with indeterminate foreign substances. He carried a gnarled walking stick that frequently punctuated his discourse with ear-piercing blows to inanimate objects. His mien was usually ferocious, but several times a day something struck him as unusual or ironic, and he erupted into an enormous good-natured roar of laughter. He was articulate and knowledgeable, and he cared deeply about each pupil. In short, he was a marvelous teacher.

Fr. Lawrence’s classes contrasted in both form and substance with my tutoring sessions in Tusculum. Adjusting to this change was not easy. In the mornings we concentrated on the Trivium[8] that is the mainstay of education in monasteries. We studied no ancient Greek writers, but we read works of St. Augustine as well as ancient works by Terrence, Juvenal, Virgil, and others. The afternoons were completely different. Fr. Lawrence began by demonstrating a new approach to arithmetic. He insisted that his students abandon the system of ancient Roman in favor of Arabic numerals.[9] He showed us that all computations were much easier when the ten Arabic characters were systematically employed. The transition was difficult for everyone, but after mastering the curly script, I could execute any calculation in less than half the time with far fewer mistakes. Once we had memorized the digits and mastered arithmetic, Fr. Lawrence introduced us to the abacus, a device that allowed us to perform difficult calculations even more rapidly. Previously I had found working with numbers irksome and difficult, but Fr. Lawrence had a knack for making exercises seem interesting.

Over the years that I spent in Fr. Lawrence’s classes other topics were added to our afternoon curriculum. We practiced the Arabic method of solving complex problems called “algebra.” Fr. Lawrence also made us learn the ancient Greek techniques of working with shapes and figures. We came to internalize many of the principles of mechanics from examining strange and complicated devices with springs, gears, and latches. A few employed counterweights to such startling effect that most Christians would condemn them as witchcraft. We learned enough astrology[10] that we could differentiate the stars that rotated in the same path every night from the handful of bright dots that appeared to move in a haphazard fashion. We used an astrolabe to determine the time in the middle of the night. Fr. Lawrence demonstrated the astonishing fact that the earth on which we traversed every day was, in fact, a huge sphere with a circumference that we could calculate! We examined and cataloged the composition of various concoctions. We never learned how to transmute lead into gold, but many secrets of the alchemists were revealed.

Fr. Lawrence had been a pupil of the most brilliant of all pontiffs, Sylvester II. In fact, many of his wonderful machines were bequeathed to him by the pontiff. Fr. Lawrence told us that Gerbert, as he always called his mentor, was probably the smartest man in the world and certainly the most learned Christian west of Constantinople. We learned that Pope Sylvester had planned to join forces with his pupil and benefactor, Emperor Otto II, to uplift the spiritual and intellectual values of western Christians. The emperor even established his headquarters on Italian soil. I was shocked and angered to learn that ignorant and superstitious Romans besmirched Pope Sylvester’s reputation and that both the young emperor and the pontiff had been assassinated[11] by thugs from Sabina before their noble plan could be implemented.

For more than five years I attended Fr. Lawrence’s classes, with only one extended absence that will be explained in due course. The early lessons took place in Rome, the ones in later years in Amalfi. During the Roman period I resided at Scuta, my family’s palace in Trastevere. This change of residence necessitated that I find a suitable substitute for the old shed in Tusculum in which I fortified myself for my epic struggles with Satan. On one of my postprandial strolls in Trastevere I discovered a partially obstructed path that led up a hill to a dilapidated watchtower that had been abandoned for decades, if not centuries. It suited my purposes admirably.

As the years went by my classmates came and went. For many the subject matter was simply too challenging. Others struggled to adapt to Fr. Lawrence’s unique approach to imparting understanding. A few were withdrawn by well-meaning but ignorant parents in reaction to Fr. Lawrence’s widespread but undeserved reputation for witchery.

Two classmates became influential figures in my life. Gerard[12] was an advanced pupil when I first began attending the class. He was a few years older than the other students, and, unlike most, he lacked noble upbringing and sponsorship. Furthermore, he refused to disclose anything about his past or his origins. His appearance was noteworthy primarily for the fact that it was so unremarkable. He was of medium height with a thin build. His nose, ears, and eyebrows were undersized; his lips were thin; his eyes and hair were the same dull brown. He always seemed to be cold; even on the hottest days he wore heavy woolen garments and boots rather than sandals. Nevertheless, I never noticed him perspiring.

The most memorable thing about Gerard's appearance was his gait. The only thing that his fellow students knew of his background was that he had apprenticed for a blacksmith. An anvil had crushed his foot, leaving him with a pronounced limp. The injury also limited his participation in the students’ games. We often asked him to show us his damaged foot, but he refused. A few fellows plotted to get a peak, but he foiled their best efforts.

Although we shared few interests, Gerard and I became friends with complementary skills. My abilities exceeded his at calculations and textual exegesis. His prowess in alchemy occasionally astonished even Fr. Lawrence. Also, with only a cursory inspection of any device Gerard could also internalize the principles underlying its mechanisms. The fact that each of us gladly helped the other with his weaker subjects became the basis for our lifelong friendship. Everyone needs such a friend; I was lucky to find one.

The other memorable character was the despicable Toad. In my eighteenth year my father, of all people, escorted into the school a diminutive rapscallion named Hildebrand. He was introduced to us as a young man of extraordinary talents. The mere act of writing his accursed name sends spasms of pain to my swollen joints. Therefore, the reader must excuse me if I refrain from such torture in the rest of this manuscript.

At first the other students were amused that the term “man” could be applied to such a runt. If he had been able to stand on his own shoulders, he still would have been the shortest person in class. “Go ahead, young fellow,” continued my father, “show them what you can do.”

The Toad effortlessly executed a headstand and began reciting the Gospel according to John, in the Latin of St. Jerome. After he completed the first chapter he popped back up to his feet in one smooth motion. “I have memorized the Pentateuch, all four gospels, and Acts,” he croaked. “What would you like me to recite next?”

“A most impressive performance,” said Fr. Lawrence addressing the dwarf by name. The priest set his hands on his knees to bring his head down closer to the Toad’s level, wiggled his eyebrows, and continued, “But in this class we do not, as a rule, memorize our lessons; we strive here for understanding, not rote. We patiently probe, analyze, and document the principles that govern all aspects of divine creation.”

The Toad announced immediately that he intended to become a monk like his uncle, the prior of the Aventine monastery. The Toad's parents had consigned the pest there when they could no longer tolerate his noxious presence. The Toad described his monastic mission as more catholic than usual. He intended to travel the world working to restore the Church to the principles of the Bible. Most students lacked plans for the next day; this runt had already charted the course of his entire life.

Those who made the mistake of disputing his claims inevitably found themselves engaged in lengthy verbal exchanges in which the Toad subtly twisted their arguments upon themselves. I soon learned to treat him with the same respect that I accorded a scabrous weasel.

The Toad labored as diligently as anyone at his studies, but he continually complained about them. For him the Bible was the source of all knowledge and understanding. He balked loudly if a lesson did not involve Holy Scripture, and he denigrated mechanics, astrology, alchemy and any other rigorous endeavor. When Fr. Lawrence was not in earshot he professed to his fellow students that they could not possibly aid him in his quest to purify the Church, as if Christianity needed direction from his ilk.

The low-born creature could not keep his elongated tongue behind his teeth. He evinced no compunction against criticizing older students and those from exalted families. He casually approached other students and interrupted activities in which they were engaged. He locked the gaze from his close-set eyes upon whomever he was addressing with extremely disconcerting effects. Once those orbs captured yours, it was difficult to break their grip. Some suspected that sorcery was at work, but I never credited the loathsome little beast with such powers.

I never mentioned my family to him, but the Toad eventually learned that the Holy Father and his predecessor were my uncles. Instead of showing me the respect that any civilized person might render, he badgered me with inquiries about their habits. He demanded to know which decisions were made by the pontiff and which were delegated to others. I admonished him in no uncertain terms that while the Holy Father and his deputies, like rulers everywhere, exercised their judgment when administering his lands, the Holy Spirit inspired all decisions about the Church. Despite the Toad's annoying persistence I never disclosed the few details to which I was privy. Instead, I calmly advised him to focus his mind on the lessons that Fr. Lawrence had assigned us. Yet I occasionally overheard him dreamily wondering about what it must feel like to sit on St. Peter's Throne. He clearly longed for the feel of the tiara on his oversized skull.

How to deal with the Toad was a question that I confronted for most of my life. The obvious answer would have been to administer a thrashing or two to the miserable creature when we both were young. More than once over the ensuing years it occurred to me that if I had just finished the job, my later life would have been infinitely more enjoyable, and the Christian Church would have been spared his insidious and perduring influence. Had I chosen that option, his stunted physique would have almost guaranteed my success. I could then confess the sin, do my penance, and receive absolution. However, such an episode would doubtless have showered seriously untoward consequences on me from both my father and my teacher. In retrospect I judge that it might have been worth the risk.

On one occasion I approached Gerard about dealing with the Toad. His face betrayed his amusement at the maddening discontent that this vermin could produce in me. Gerard’s words ring in my ear to this day. I can visualize him resting his hand on my shoulder and I can almost hear his gravelly voice. “Theophylact,” he said, “forget about the Toad. Concentrate on what you want to accomplish and amass the skills and knowledge to succeed.

“I understand that the brat annoys you, but participation in his games is a mistake because he sets the rules. Never let the opponent dictate the rules in a contest. Treat him as you might a scab from a wound received from a training session with your brother. It itches, and it is bothersome. However, picking at it accomplishes nothing. In fact, it can cause renewed bleeding that retards the healing process. If you ignore it, it will eventually dry up and go away.

“He is obviously clever and ambitious, but he is also powerless. Watch and study him as long as he remains powerless. If he begins to get under your skin, politely excuse yourself and walk away. Remember this: if it ever becomes crucial to deal with him or anyone else, know that you can count on my assistance. I have resources.”

The last sentence he pronounced calmly and deliberately. I looked Gerard directly in the eye in order to gauge his sincerity. After all, I could certainly administer a severe beating to the Toad with no help from a cripple. If the dwarf ever harmed me, he would face my father and my brother, and no one in Rome was up to that task. Could Gerard be serious about me needing his so-called resources? To eradicate any doubts that I might have harbored about his sincerity he narrowed his gaze and leaned in slightly in my direction. I saw something in his eyes that I had never beheld before—a reckless intensity that I came to know and appreciate in later years. At that point the attribute was probably just in its gestation period.

Perhaps I should have embraced his advice and ignored the twerp’s indefensible behavior and mannerisms. At least Gerard’s advice accomplished this much: it convinced me that I should patiently plot the best method for driving the abominable cockroach back to his proper station forever. That Odysseus overcame Polyphemus by craft rather than force was a good lesson. When the obnoxious showoff snatched another fly out of the air—he never missed—and pretended to stuff it down his throat, I feigned disinterest and went about my business.

[1] In the early eleventh century the Byzantines controlled most of the current Apulia and Calabria, the heel and toe of the boot. Adjacent to these holdings were four independent principalities (Benevento, Capua, Salerno, and Spoleto) as well as the Duchy of Amalfi. In the early eleventh century Sicily was still a Saracen territory.

[2] The monastery of St. Mary in Rome, commonly known as the Aventine, was affiliated with the huge Benedictine abbey in Cluny founded in the tenth century. During this period the abbot in Cluny was St. Odilo. It is almost impossible to overstate the French abbey’s wealth and influence on Church affairs in the eleventh century.

[3] The speaker used a different exclamation involving cabbages, but a literal translation would be completely meaningless in English.

[4] 1024.

[5] Theodora was the sister of Count Alberic and the two pontiffs, Benedict VIII and John XIX. She was the aunt of the author and his brothers.

[6] At least one chronicler has placed Lawrence in the abbey at Montecassino during this period. He was named Bishop of Amalfi in 1029.

[7] 999-1003. Gerbert d'Aurillac, who became Pope Sylvester II, studied in schools in southern Spain that were run by Muslims.

[8] The Trivium consisted of grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

[9] Arabic numerals were known in Europe much earlier, but their use did not become popular until Fibonacci’s publication of Liber Abaci in the early thirteenth century.

[10] In the twenty-first century we would probably call this “astronomy.”

[11] The deaths of both men were certainly sudden and unexpected, to say the least.

[12] The “Gerard” mentioned may be the mysterious figure Gerhard Brazutus, who was accused of monstrous crimes in the writings of Cardinal-Priest Beno, also known as Benone, Benno, or Bruno.