Chapter 4: Regal Pomp and Shocking Discoveries

In the spring of 1026 Rome buzzed with news that the ambitious Archbishop Aribert of Milan had publicly presented the Iron Crown[1] to Conrad II, newly elected King of the Germans. My family's interest centered on the descent into Italy by the king and his formidable army. Pope John immediately dispatched envoys to invite the king to Rome to receive the crown of Holy Roman Emperor from the Holy Father’s hands, just as two centuries earlier Pope Leo III had crowned Charlemagne.[2] The inhabitants of Rome were hastily mobilized to prepare for the king’s arrival. Circumstances, however, forced Conrad to lay siege to the city of Pavia. The pontiff therefore decided to journey north to invite the monarch personally. My brother Gregory commanded his military escort.

Because I had never seen a ruler of another land, the king’s impending visit excited me. However, a different king, Canute, the lord of the English and Swedes, strange peoples of northern realms, arrived in Rome with his wallet and staff[3] halfway through Lent. King Canute was an exceptionally large man with wavy hair the color of harvested wheat. It flowed down to the middle of his back. Although dressed as a humble pilgrim, he clearly had brought much of his treasury with him. In addition, despite having traversed the entire Via Francigena, he arrived in possession not only of great wealth but also vigor and religious ardor.

By the time that King Canute's large contingent reached Rome, the date for Conrad II’s coronation had been set for Easter Sunday. Delighted to meet both the German sovereign and the Holy Father, King Canute and his spiritual guide, Bishop Lyfing, spent the intervening weeks purchasing sacred relics, making eleemosynary donations, and visiting the city's grand and historic churches and shrines. My father offered to arrange housing for them in Tusculum, but they insisted on camping outside the city’s walls.

On Maundy Thursday King Otto arrived at the Porta Flaminia with his wife Gisela, his entire army and retinue, King Rudolf of the Burgundies, and the papal party. King Otto served as strator[4] for the Holy Father as they passed through the gate. My father officially welcomed the visitors to the city, and Cardinal-Priest John Gratian, after a prayer that lasted as long as most Masses, led a procession to the Lateran during which he chanted the litany of the saints. I barely suppressed my laughter when he tripped on a paving stone. Only by leaning awkwardly on his crosier did he avoid falling on his face. People lacking my self-control diminished the solemnity of the occasion by only a little.

The imperial coronation took place in St. Peter’s. Mass was celebrated by the Holy Father with more than a dozen bishops and countless priests and deacons in attendance. The emperor was anointed and crowned by Pope John in a manner designed to reenact Pope Leo III's performance centuries earlier. His Holiness politely reminded the emperor of the sacred obligations that Charlemagne had accepted for himself and his successors. He agreed to defend the Holy See and the entire Petrine Patrimony against threats from all quarters. To assure that everyone comprehended the importance of his pledge, Pope John vividly described the dangerous ambitions of the Greeks, Normans, and the Saracens in the south and encroachments on papal lands by voracious local nobles. The emperor and the empress accepted the tokens of their offices with grace and solemnity.

Several days of celebration ensued, after which Pope John conducted a synod in the Lateran. A monk from the Aventine served as official scribe, but I was authorized to take notes and provided with a stylus and tablets.[5] King Canute was allowed to dominate the first phase of the proceedings. He addressed us in his harsh native tongue; Bishop Lyfing translated into Latin. The oration lauded the sanctity of the occasion and the joyful experience of his pilgrimage. The king's phenomenal memory allowed him to describe in vivid detail every chapel in which he had worshiped during his long journey and every relic added to his collection. He emphasized the overwhelming lift to his spirit from being in the city of the apostles Peter and Paul. King Canute treasured the privilege of praying near the remains of St. Peter himself. He regretted only that most of his subjects could not share the thrill.

The sole discordant note in this oration, which lasted longer than a High Mass, was his vociferous harangue against the high tolls exacted from pilgrims. Pope John assured him that he would do everything in his power to make sure that charges were reduced to reasonable levels. His Holiness also used the occasion to remind the king that his subjects had fallen behind in the payments associated with their obligation to St. Peter.[6] King Canute testified that he had been unaware of this oversight. He condemned this affront to the Holy See and solemnly assured the Holy Father that he would make certain that the problem was resolved.

I dutifully recorded the proceedings, but at some point in the intervening years many details have fled from my memory. For example, I recall none of the emperor's words, but my mind’s eye pictures him as silent but attentive and thoughtful. A man of decisive action, not voluminous words, he eventually tired of the lengthy speechifying[7] The empress was also taciturn. Having tucked her blonde tresses beneath the crossed hands upon her lap, she sat for long periods upright and nearly motionless between the sovereigns.[8]

No royal figure made as strong and lasting an impression on me as a lowly member of Conrad’s staff, a cook’s assistant. Probably no one else in the synod even noticed her. I never learned her name. Her eyes drew my attention. The irises were a strange mixture of blue, brown, grey, and green. What made the orbs so startling was that they did not move in unison. At first I thought that I must be mistaken. However, when she gazed right at me with the right eye, the left was unquestionably pointed downward and towards her nose. I could not suppress a gasp.

I found myself compelled to spend time in her vicinity. She was at least as old as my mother and by no means comely, but for some reason my gaze was drawn to her face. I tried to remain inconspicuous, but inevitably my presence drew her notice. Toward me she extended a rude gesture demanding my departure. I quickly complied, but I also returned before the next bells. On the morrow she espied me again and approached waving a ladle and shouting in her barbaric language. It sounded more like coughing and sneezing than human speech. As I hastily retreated, I noticed a brown growth below her left ear approximately the size of a thumbnail.

The following morning I attended a speech declaimed by a bishop whose name evades my recollection. Satan snatched control of my imagination and directed it towards this woman’s appearance. I envisioned her cavorting around the campsite while performing decadent acts with her ladle. She winked at me with her wayward eye and invited me with gestures of her tongue and forefinger to lick the spot on her neck. I could actually taste it. It was simultaneously sweet and pungent with a crusty surface.

While this repugnant image dominated my thoughts, the bombastic bishop gave emphasis to an argument by banging his fist on the table before him. Startled from my reverie, I glanced first at him and then at my lap, where my gorzo distended my garments to a noticeable extent. I quickly covered my lap with a tablet and concentrated on calling to mind images of the Savior’s last days. It was in vain. The German woman continually intruded on my imagination in ways that are not suitable for revelation. I exerted an intense effort to focus my attention on recording the bishop’s ideas on the tablet spread across my lap, but the pressure generated by this action exacerbated the situation below until the natural conclusion. A small groan may have escaped. Several heads swiveled in my direction. I resolved at once to avoid further public humiliation by increasing the frequency of my visits to the watchtower to at least four occasions per day.

Most would not deem that tower a pleasant place. It was perhaps eleven times as tall as a tall man. Only the ground floor was readily accessible, and that was overgrown with moss and noxious vegetation. Over time I collected a few objects within its walls, including a discarded chair and table that Gerard had repaired and a pair of moldy cushions. There was no source of light within, and the entire structure included only two small windows. If I neglected to bring a lantern, I could scarcely see at all inside the tower. Since it would be strange for me to carry a lantern on a bright sunny day, my vision inside the tower was better on dreary and overcast days and near dawn or dusk.

The sky was sufficiently overcast on a late October afternoon in 1028 that I needed to carry a lantern on my stroll. The devil seemed to be occupied elsewhere; which was unusual. I forced open the door to the tower and lit the lantern. Seated on a cushion I imagined myself at the head of a brigade of Christian men-at-arms driving the Saracens from Sicily. As I led a bold, even reckless charge against the infidels, my gaze fell upon the tower’s dilapidated staircase that I had never previously inspected.

The tower had once comprised three stories[9]. The upper two had long since collapsed, and the staircase up to the top chamber was in shambles. The roof on which the sentries once took their positions still appeared to be intact and relatively sturdy, but the upper floors were hopeless. After my imaginary triumph over the Saracen hordes, however, I noticed that enough staircase remained that if I precisely balanced myself at one spot and thence executed a mighty leap, I might be able to reach a small fragment of the middle floor that still jutted out from the south wall. I saw only one way to determine whether that ragged ledge would hold my weight. I moved the table to a convenient position in the room, set the lantern on it, and aimed its beam at the portion of the second floor that I hoped to reach with my leap. The first five times that I attempted this I slipped and fell to the ground. In each case I landed on my feet. My sixth attempt nearly succeeded, but my hands were unable to gain purchase. When I fell I did not land quite right. My ankle felt a little sore after that attempt, but I forced myself to try again. After one more painful failure I maintained my grip on the eighth attempt and managed to pull myself up to what remained of the middle floor.

From this vantage point I spotted a slightly larger piece of the uppermost floor that remained in a roughly comparable condition. However, I saw no way to cross the gap between the ledge on which I was situated and that loftier spot. Intense creative thought sparked an idea, but its execution needed postponement to a future visit. I let myself down to the floor very gingerly. My ankle was beginning to swell. Walking on it would surely aggravate the condition, but there was no use delaying it.

I limped alongside the river and then crossed the bridge to Tiberina.[10] A medic named Brother Polycarp wrapped my ankle, lent me a crutch, and advised me to avoid putting weight on it for three days. Meanwhile I thought of little besides my plan for reaching the top floor. When I was finally able to return I overcame the devil's advances and then set to work.

I had borrowed from the blacksmith a sturdy hammer and a dozen iron wedges half as long as my arm. I planned to pound the wedges into the masonry between the stones at regular intervals in order to provide myself with handholds and footholds on the interior wall. The task proved more difficult than I anticipated. In some locations too little space remained between the stones to affix the wedge firmly no matter how much I pounded. Moreover, the mortar occasionally crumbled at the first touch of the iron, clearly indicating that no wedge could be securely inserted there. I never successfully implanted more than two wedges in one session.

The other problem involved leverage and balance. Driving in wedges higher on the wall than I could reach from the ground, required ascending the wall and balancing on wedges already in place. The higher that I climbed, the more precarious hammering became. I grew frustrated, especially when the wedge or the hammer slipped from my hand, as frequently occurred. I constantly struggled to avoid falling, knowing that even one fall might be catastrophic. The work was exasperating and exhausting, but I persevered. Tusculans never quit.

Memories from bygone decades often seem strangely vivid to me. I still remember distinctly that I was engaged in hammering the nineteenth wedge when I made a remarkable discovery. One stone appeared somewhat different from the others. It was a bit to the left of the pair between which I was about to hammer a wedge. From my position I could detect thin gaps between the peculiar stone and the surrounding mortar on both sides and the top. Around other stones the mortar was flush with or even overlapped the stone’s surface. Also, I saw small grooves on the side of this particular stone. I judged that I might be able to remove that stone from the wall if I were somehow able to apply enough force and leverage. I temporarily abandoned my goal of reaching the top floor and concentrated on extracting the stone.

During the next two visits I managed to insert four new wedges a few feet beneath the stone. When I climbed to the highest wedge I could see an indentation on the left side of the stone as well. The stone was designed to be removed at will. The person extracting it would have been standing on the floor rather than on two wedges perilously inserted into the wall. That area of the wall was probably covered by tapestry, artwork, or furniture that was removed long ago.

I worked for as long as I dared, but the cursed stone would not budge. The effort left me hot and tired and my fingers sore. I returned to Scuta, but the the stone haunted my thoughts. On the following day I approached my friend Gerard. I expected him to be impressed by the clever plan and skillful execution that led to my discovery. He simply asked “Why not a ladder?”

I sheepishly admitted that in the four weeks during which I had toiled on this project, the common ladder had never occurred to me. Why would it? I was inside, and in my experience ladders were used on the outside of buildings. When indoors one used stairs, or, if necessary, wedges pounded into walls. Also, I was in the woods. Ladders were for houses and businesses, which were, for the most part, found in urban and commercial areas. I could have labored for years in that ruined tower without ever considering a ladder.

The next morning Gerard became the first outsider to enter the tower. We carried two borrowed ladders to the tower, and, while Gerard rested to relieve the pain in his bad leg, I lashed them together to form one ladder long enough to reach past the stone in question. Gerard steadied the bottom of the ladder while I climbed. The ladder provided much surer footing than the spike; my leverage was much better. Nevertheless, when I pulled on the stone I could not make it budge.

Gerard asked me to strike the stone from a side to see if I could detect any lateral movement. I reported that it seemed to move a little. He then advised me to waste no more time and effort. Instead he requested the precise dimensions of the stone and of the indentations on the sides. I descended, went outside, and fetched some straight sticks. I climbed back up and drew my knife to mark the required distances for him. “Take your time and be precise,” Gerard admonished. After I climbed back down, he placed the sticks that I had scored in his pouch, helped me tote the ladders back to the workers, bade me farewell, and predicted that we would remove the stone within a few days.

When I saw my friend in class in Rome the next day, he did not mention the project. This silence was usual from the least garrulous of God’s servants. On the second day following, however, he drew me aside with the single word, “When?”

I asked him to accompany me to the tower on the following afternoon. He then led me to his quarters and showed me his machine. It looked like a cumbersome weapon with numerous gears, a large handle, and several thumbscrews. The thin sharp protuberances on either of its sides could certainly inflict injury. They were sturdy and sharp. I could not fathom the usefulness of the device in extracting the stone, but I trusted his mechanical acumen.

We borrowed the ladders again and transported them to the tower with Gerard's device in a wheelbarrow. We lashed the ladders together and positioned the top of the resulting long ladder slightly below the stone. Gerard, who had looped my hammer into his belt, did the climbing. He seemed uncomfortable with heights, and he winced every time that he put weight on his game leg. He lifted the heavy machine up rung by rung, keeping it near the level of his head. At last he reached his goal, a remarkable achievement for a cripple. Balanced on two rungs he boosted the machine toward the stone and then worked the machine's blades into the cracks on either side of the stone. Descending a couple of rungs, he set the contraption on the ladder while the top of his head held it in place. He caught his breath and then twisted the thumbscrews on the mechanism. After he was satisfied, he again approached the stone with the devise in front of him. This time he managed to insert the two thin edges of the device on either side of the stone, but they only penetrated a very short distance.

After several more adjustments my friend was able to work both blades more than a thumb's width into the narrow gaps on either side of the stone. He then held the device in place with his left hand while he retrieved the hammer. After two or three dozen carefully placed strokes, the two blades had completely disappeared from view, and the device remained in place without Gerard’s support. Anguish was written on his face as he slipped the hammer back in his belt. His features contorted in pain as he descended. On reaching the ground, he limped over to a cushion and threw himself on it. He lay motionless as he gasped for breath. At last he handed me the hammer and reported that he was totally spent; the rest was up to me. My job was to move the ladder to the previous day's position, climb up, and turn the mechanism's handle. Before I began, he stopped me. “One question first: how are we dividing whatever is hidden behind the stone?”

As obvious as this seems in retrospect, never had I considered that valuables might lie behind the stone. Curiosity was my sole motivation. “Well,” I reasoned, “I probably would never have been able to budge the stone without your ideas and your skill. You should have two portions for each of mine.”

“Nonsense; equal portions. One additional possibility, however, remains. What if the discovery is not easily divisible? In that case either we should agree to destroy it, or one of us must buy the other’s share. I propose a price of half of a pound of gold. What say you?”

My eagerness to see what was behind the stone stifled my ability to think of anything more appropriate. I clambered up the ladder and attempted to turn the crank. It required a supreme effort from both arms to turn it, but as I did, the stone slowly ground its way toward me. After the first thumb-width or so the stone seemed to move a little more easily. I turned the crank as hard as I could, and the stone moved a little more rapidly. Before I realized what was happening, the stone was free and falling toward the floor. Instinct made me try to grab it with both hands. Unfortunately, Gerard’s creation had evidently been held in place by the stone’s bulk. When the stone plummeted earthward, the device followed as a chick follows a hen. Its sharp blades slashed my hands and arms in several locations, and crimson streaks appeared. A feral scream forced its way past my lips, but I managed to stay perched on the ladder.

I descended as rapidly as I could. Gerard ignored his own pain to attend to my wounds. He stanched the bleeding using strips of cloth that he withdrew from within his jerkin. From his satchel he produced three yellowish leaves. “Chew on these,” he said, “and extend your arms well above your head.”

Some time passed before I felt sufficiently recovered to resume the task. Meanwhile Gerard inspected his contraption and the stone. The machine itself was ruined, but, since the stone had been removed, that mattered little. Some parts were salvageable. A crack appeared in the stone, but it remained in one piece.

With my arms bandaged and my pain lessened, I carefully scaled the ladder again to inspect the space. I found therein a leather bag tied shut with a leather cord. Inside was a rather heavy object that appeared to be a cube or something similar. When I looped the cord around my shoulder to climb down with my hands free, the leather fell to pieces. So, I carefully kept the bag and its contents balanced on a rung in front of me as I tentatively descended to the floor. Every time I took a step down I moved the package down one rung. When I reached the ground, I removed the tattered cord and withdrew the prize. It was a plain wooden casket, with corners reinforced with brass. I could not open it because the hasp was secured by a padlock.

“It is locked,” I remarked to my friend.

Gerard seized the box from me and shook it. The only thing that he said was, “Not heavy enough.” Then he examined the lock. Due to the dim light he needed to hold it close to his face.

“Maybe we can pry it open. Go out and find a rock about so big.” He held his thumb and forefinger apart to demonstrate the size that he wanted.

I exited through the door, rummaged around in the nearby vegetation, located a suitable stone, and then returned to the tower. The lock was open. Gerard explained, “The lock evidently lost its power over time. I jiggled it a little, and it snapped open. Poor craftsmanship.” He then released the hasp from the staple. Inside were five rolls of papyrus, each about as thick as a fist.

“As I suspected. Was anything else in the niche?” Gerard asked. Ignoring his question I retrieved the lantern in order to peruse the contents. I unrolled a bit of the leftmost manuscript and began to read. The text was in the vernacular, but the phrasing and usage seemed strange. It appeared to be someone’s journal. The first roll that I examined followed the format of dated entries. The first date was April 11 of 53. The manuscript was therefore at least seventy-five years old. What an incredible treasure!

Gerard repeated, “Was anything besides this worthless papyrus in there?”

After I informed him that I detected nothing else, he remarked, “Well, at least it is easily divisible. All that is required is cutting one of the rolls in two. My knife might not be up to the task, but we can probably borrow a saw. I wonder if it is even worth the effort.”

I protested that such an act would destroy the manuscript, which would be an ineffable tragedy. I breathlessly offered to buy his share for our previously specified price in gold.

“Done,” Gerard replied with no hesitation whatever. He then inquired how I planned to explain the gashes on my arms and the blood spattered on the ladder. For the first time I appreciated this difficulty. I needed to avoid arousing any suspicions among my relatives and friends. I certainly wanted no attention drawn to my tower. However, the importance of inventing a convincing explanation failed to inspire my imagination to produce anything remotely plausible.

I seated myself on a makeshift stool that I had constructed. Noticing that a few drops of fresh blood leaked from my wounds, I again stretched my hands above my head. Gerard, a man of few words, dragged a stool near to mine, sat down, and explained how to deal with such a situation. “In a position like this you need to concoct two explanations. In the first your behavior is honorable, even praiseworthy. It can be dubious, not too outlandish. You expect it to be questioned, but you must act offended at the first challenge of your veracity. This is very important. When the story becomes indefensible, you reluctantly admit to the truth of the second tale, which portrays you in a somewhat shameful or embarrassing light but also provides a more reasonable explanation. People will be happy to accept it if it makes them feel superior to you.”

“Why do you say that? I never enjoy feeling superior.” I asked. My reply elicited only a grunt. Gerard described possible elements to be included in the first explanation. “Can you convincingly tell this account? You happened upon some fresh boar tracks in the woods—exceptionally wide and deep. You followed the prints of the oversized beast back to its lair. Suddenly, to your horror, the huge hog burst from the brush and charged you. You screamed a short prayer to St. Theophylact; is there one? If not, choose another. With courage enhanced by divine intervention you bravely stood your ground as the beast charged unabated. At the last moment you shielded your vital parts from the razor-sharp tusks. Its attack was diverted just enough to save your life. Then, in a desperate act you boxed its ears and sent it scampering back into the bushes. Your superficial cuts with no puncture wounds will give lie to this story after a little questioning. Be sure to act insulted at first when someone notices this.

“Your second tale requires much less embellishment. It must be simple. Here is an idea: I taught you how to juggle three knives at once, but your enthusiasm to master the trick overwhelmed your good sense. No one should be surprised by the fact that you foolishly practiced with sharp knives, and occasionally your coordination was insufficient to the task. Pay attention; I will show you how the trick is done. It is not difficult but it requires practice.”

Gerard and I stepped outside. He found three sticks that were roughly the size of knives. He showed me how to spin them at just the right rate and how to time the tosses between my hands. As usual, my right hand absorbed these lessons much more readily than my left. Fortunately, the rhythm of the maneuver was easy to learn even in my wounded condition. Most of the practice time was spent training the left hand to cast the stick in an arc that allowed the right one to catch it.

The undeniable discrepancy between these two symmetrical neighbors has always puzzled me. Both hands were controlled by my mind. What invisible injury rendered my left so inferior at learning actions such as these? My right hand is much better and stronger at absolutely everything. Decades have passed, and I have never found an answer to this question.

Upon my return to Scuta Gerard’s prediction was fulfilled. My brother Peter, after asking several pointed questions about the alleged charge by the boar, demanded to inspect my wounds. He then exposed my claims. I protested at first, but my defenses were feeble. I then in a stumbling fashion admitted that I had invented the story of the charging boar. I compensated for misleading him by showing him how I could juggle three sharp knives at a time. I insisted that the stunt required very little talent but considerable practice. A few days later I noticed with glee that his forearms were also festooned with red stripes.

For the next several months[11] my visits to the tower were of longer duration than before. I needed the extra time to transcribe the manuscript from the papyrus to a codex that the monks had provided me. I also corrected the author’s spelling and grammar in many instances. I quickly learned that his name was Octavian, the same as my youngest brother’s. His age when he began writing his journal was slightly less than mine when I undertook to transcribe it. I therefore found it quite easy to relate to a many problems that confronted him. This affinity increased markedly when I read that his father’s name was identical to my father’s, Alberic. Octavian described his father as a very powerful figure in Rome, perhaps even more important than my own father, who answered only to Pope John.

Young Octavian’s interests often coincided with my own. We both loved to hunt, but his father, unlike mine, encouraged his participation. Octavian and his horse explored his father’s estate and the charming valley to the south of Tusculum, but he also resided in the same palace in Trastevere that was my home in the city. I learned few particulars about his father, and his mother was never mentioned. One aspect of his life varied from mine. If he had tutors or instructors, he did not mention them. His active life left little time for schooling.

A later entry provided fascinating details about Octavian’s first time with a woman, an area in which I lacked experience. In subsequent sections he meticulously described one conquest after another, often of mature women. I paid careful attention to his techniques in approaching ladies, and I really savored the diverse ways in which he pleasured himself with them. I was excited to learn that several liaisons occurred in the tower in which I was writing. It had evidently already been abandoned in Octavian's day. I often needed to fight off the devil as reading the details inevitably engendered a mental picture of the young libertine's trysts.

When he was only a little older than I was when I read it, Octavian was named by his father as Prince[12] of Rome. He must have been even younger than my brother Gregory was when my father gave him his first command. Even as his health began to deteriorate, Alberic, Octavian’s father, retained his influence in the city. He evidently felt no need to consult with others before appointing his son as Prince. It surprised me that no mention was even made of the Holy Father or any senators, patricians, or members of the clergy.

Octavian took full advantage of his lofty position. His life was one exciting adventure after another. When in Rome his favorite location was obviously the bedroom, and he was not very discriminating in his choice of partners. His father sometimes ordered him to lead troops into various territories to bring them to heel. When they had completed the assignment, they helped themselves to the physical and material treasures at their disposal. No one questioned their actions, no matter how rapacious. All Roman ladies were reportedly mad for his attentions, and the men admired his wisdom and strength.

I knew enough not to trust everything that he wrote. Nevertheless, by the time that I had finished that first scroll I also envied the lad!

Because I needed to limit my time in any session in the tower, the transcription had taken me more than a month. Even so, I was obviously devoting a great deal of time to my strolls. I could ill afford to draw any more attention to them. My greatest fear, of course, was that suspicion might eventually be drawn to my visits to the tower. The shame would be unbearable if anyone discovered my activities.

The entries in the second and third scrolls were considerably longer, and they usually covered longer periods of time. Octavian’s new responsibilities and his unflagging libertinism robbed him of much of the time that he had once devoted to his daily record. His handwriting became a little steadier, but his spelling, grammar, and vocabulary were still pathetic.

Many entries precisely described the anatomies and predilections of Octavian’s paramours. The most astounding section dealt with his ongoing relationship with a woman named Petrella, who was, shockingly, Octavian’s mother’s sister[13] and thereby the young man’s aunt. Her age, however, exceeded his by only a few years. Octavian claimed that when her husband lost his life to disease, she turned to her nephew for solace, which he was delighted to provide. She was as adventurous as he was; the journal described activities that I would have judged painful if not impossible. I learned the location of every blemish and bump on the lady’s form as well as her favorite corporal interaction. The most astounding to me was her intense enjoyment when he blindfolded her and bound her hands behind her back. Then, when she was in this completely helpless position, Octavian applied a goose feather to the soles of her feet. Never would I have suspected that any woman would tolerate, much less exult in such treatment. According to Octavian this brought her to a point of frenzy from which he took great pleasure in releasing her with brutal physicality.

Octavian had little positive to note about his relatives and associates, but he expressed great fondness for his stallion, Beltempo. He took exceptionally good care of the animal. Every day included a visit to the stables to curry Beltempo and to check that his steed's needs were met. One day a bizarre notion nested in Octavian’s brain. He decided to name Beltempo as Senator of Rome.[14] The text cited no motive for the extraordinary appointment, beyond respect for the horse,. Nor was there any mention of others' reactions. This episode confirmed my impression that neither tradition nor family ties circumscribed the young man’s actions. In this respect, of course, he was very different from me. His attitude repulsed me, but the freedom that it afforded him was undeniably attractive.

The last section of the third scroll recounted shocking events. Octavian reported that the Holy Father, Agapetus[15], suddenly died. Although only eighteen years old, Octavian was chosen by the electors to replace him. Such an election was beyond my comprehension. Why would any Christian wish a feckless youth like Octavian to be Supreme Pontiff of his Church? The journal made it clear that his father Alberic wielded a great deal of influence in Rome, but his name had not been mentioned since the beginning of the second scroll. It was unclear whether Alberic was still alive at the time of his son’s election to the papacy. Furthermore, the young man reportedly did not seek the office; the responsibility was thrust upon him.

As a child I had been taught that the Holy Ghost provides spiritual guidance to those who choose the pontiff. It was impossible for me, then and now, to understand how entrusting the leadership of the Church to this rapscallion could possibly further the ends of Christianity.

Octavian needed to participate in several days of religious ceremonies in order to attain all of the orders needed as Supreme Pontiff. His journal exposed his ignorance of and disdain for these rites. In fact, before Octavian's election, the text had seldom mentioned the Church at all. No clergyman seemed to play even a minor role in his life. No religious ceremony merited inclusion in the diary.

When I read that, to honor his uncle, Octavian had decided to change his name to John, I realized that the journal belonged to Pope John XII. My parents had often emphasized that our family's ties to the papacy dated back several generations, and I heard remarkable legends about my ancient relatives, John XI[16] and John XII.[17] These stories, however, did not prepare me for the journal's description of how the young pontiff celebrated his sacred investiture with an energetic encounter with his aunt followed by a raucous night of gambling and drunken carousing. No words can express the disgust that I felt when I learned of such ignoble acts by the Vicar of St. Peter. Nevertheless, I continued reading. The accounts generated one conflicting emotion after another.

Thereafter the tone of the entries changed dramatically. John clearly loathed his new position. His life prior to becoming pontiff had reportedly been an unbroken string of rollicking adventures unfettered by responsibility or feelings of guilt. Never did his journal hint at disappointment or grief. Octavian apparently never performed household chores or studied or did anything vaguely onerous. He never was held accountable to guidelines or benchmarks. Every Roman expected the pontiff to provide competent management of the religious and temporal affairs of the Holy See. The entries in the journal repeatedly complained about lengthy ceremonies and tedious meetings with cardinal-bishops and other religious notables.

He still arranged for frequent visits to his apartments in the Lateran Palace[18] by loose women. He even made provisions for a few of his favorite female companions to reside there. It was not a secret; everyone seemed to understand his or her part in this farce.

The senior prelates attempted to rein in the pope’s behavior, but they could not restrain the young man. He soon discovered that only the pontiff appointed cardinal-bishops, cardinal-priests, and cardinal-deacons.[19] Most of those appointed by his predecessors died within the first few years of his pontificate. He was careful in his choices for these appointments and assignment of other benefices. In every case he personally interviewed representatives from each powerful Roman family before making his choice. When he asked them “what they would bring to the office,” most understood and outlined how much their family was willing to donate in order to obtain the benefice. Those who misunderstood generally departed disappointed. Pope John found this process extremely amusing, and it generated a reliable stream of revenue.

Much of Pope John’s attention was directed toward expanding the papal territories. His journal opined that preceding pontiffs had neglected to secure the Petrine Patrimony's holdings and retake lost portions. He possessed the disposition and the resources to rectify the situation. He preferred to be clad in helm and chain mail seated on Beltempo’s back over wearing the tiara and pallium sitting on St. Peter’s Throne. He personally led troops on missions to restore the Holy See’s hegemony. After each such venture he hired a teamster to drive a wagon around the city to distribute a share of the booty to the poor. He exulted in accompanying the wagons. His assessment of these unfortunate people as pathetic but amusing creatures was insensitive. Distracted by their wretched conditions and their ignorance of larger matters, he ignored the beauty of their pure hearts and immortal souls. On the other hand, whenever anyone solicited his blessing, he cheerfully bestowed it.

Pope John’s sorties in the papal territories occasionally failed. An early entry employed a despondent tone to describe his defeat near Ravenna by the forces of King Berengar.[20] Pope John and his closest companions made a hasty retreat behind Rome's walls. They gathered in the Lateran Palace to drink wine and mourn the deaths and injuries of companions. The occasion began on a somber note, but as the wine flowed more freely talk turned to how to stop Berengar from pressing his advantage. Some feared a threat to the city itself. An elderly cardinal-priest reminded Pope John that on desperate occasions pontiffs had relied on the protection of the emperor beyond the mountains. This possibility intrigued the brash young man. The imperial crown had not been awarded in anyone's memory, but the idea so captivated Pope John that he immediately resolved to offer it to King Otto of Germany[21] in return for protection from King Berengar and any other threats to the Patrimony. He assembled an official delegation to cross the Alps and present this proposition to the German monarch.

King Otto was pleased. He agreed to visit Italy to be crowned by Pope John. The king was accompanied by his wife, his retinue, and a formidable army. Cardinal-Bishop Benedict warned the reckless pontiff to exhibit high standards of behavior while Otto was in Rome. The king was reputedly an upright gentleman with no tolerance for foolishness, and his wife Adelaide was considered one of the most virtuous women in God’s creation.[22] The pontiff reluctantly agreed to relocate his female companions outside of the Lateran Palace during the king’s visit, and he promised to conduct himself with probity.

Otto's party was escorted through the streets of Rome in a solemn religious procession that included a dozen bishops and cardinal-priests. When they met the pontiff both King Otto and Queen Adelaide prostrated themselves on the floor and kissed his slipper. The pontiff found this scene extremely amusing. He even boasted that he wiggled his toes in Adelaide’s face. He then welcomed the couple and bestowed his blessing on them and their empire.

The journal dismissed King Otto as an old man[23] who was no match for the pontiff at bargaining. His wife was another matter. Pope John treated her more like the king’s daughter than his bride. She was nearly two decades younger than King Otto, and the pontiff quickly surmised that their relationship seemed based more on respect than physical attraction.[24] The journal disclosed, in fact, that he detected flirtatiousness in her glances toward the young pope.

The king expressed a desire for the German city of Magdeburg to be elevated to the rank of archdiocese. He intended the city to become a base from which missionaries could set out to convert pagans in the Slavic regions. At first the pontiff's interest in this plan equaled his concern for the disposition of mule carcasses, but, ever mindful of bargaining tactics, he feigned concern and demanded details. When he learned that the project was Adelaide's idea, he moderated his tone, expressed his approval, and asked what the Holy See could do to assure success. He also requested a comprehensive briefing so that he could monitor the campaign's progress.

Subsequent meetings on this subject became less and less crowded. Bye the bye the pontiff secured a private tryst with Adelaide, and shortly thereafter he had, his journal claimed, no difficulty in seducing her. In fact, his advances were reportedly quite welcome. Otto, she complained, had neglected her for several years. She admitted to the Holy Father that she sometimes found herself thinking longingly of her one-time fiancé, Adalbert,[25] from whom Otto had delivered her many years earlier. The young pontiff speculated that it was no coincidence that the man designated as the first Archbishop of Magdeburg was also named Adalbert.[26]

My usually sturdy youthful hand trembled so much while I recorded this encounter that the text in my codex was scarcely legible. The prospect of the Vicar of Christ seducing a king’s consort stretched the bounds of my imagination. Could this outrageous conduct have actually occurred? Was the pontiff lying or perhaps fantasizing? If not, did no one learn of this perfidious crime? I obtained no definitive answer to these questions.

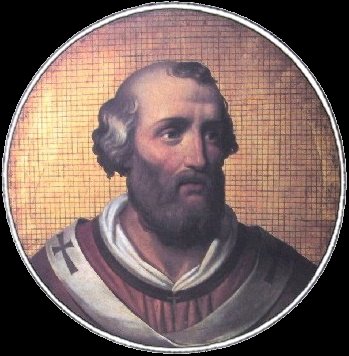

The account brought to mind the startling contrast between this opprobrious comportment and the unexceptionable behavior of my uncle, Pope John XII’s ultimate successor, descendant, and namesake. It was absolutely inconceivable that my uncle would have even considered engaging in such conduct with Gisela, the current emperor's wife. My young mind could not imagine that such a scandalous event could transpire then or now.

Pope John agreed to allow Otto to appoint not just the Archbishop of Magdeburg, but a few other bishops as well. The pontiff cared so little about them that he neglected to record their names or sees in his journal. In return the king affirmed the Donation of Pepin and made his own donation. It expanded the Petrine Patrimony to include much of the peninsula. He also pledged to drive Berengar and Adalbert from the papal territories. In return Pope John swore allegiance to Otto and promised never to engage in alliances against him. He also swore that all future popes would be elected according to the canons and that the name of the chosen man would be submitted for the emperor's approval. As appalling and indefensible this limiting of ecclesiastical authority was, John knew that he would almost certainly be dead when that this clause took effect, and he had no interest in who succeeded him on the throne. Nevertheless, before he consented he complained bitterly to the monarch’s negotiators about how this would hobble the institution of the papacy. It shamed me that a member of my family did this.

Pope John then anointed and crowned Otto as emperor in St. Peter’s. He also crowned Adelaide as empress, an unprecedented act that must have provoked rumors. The journal did not disclose his motive for the second crowning, which made me wonder whether he compensated her for her favors or set the stage for subsequent political maneuvers.

The journal reported nothing positive about one prominent member of the royal contingent, Liutprand, whom Otto had appointed as Bishop of Cremona a few months earlier. Pope John criticized his manner of speaking as obsequious when addressing Otto or Adelaide and condescending when talking to others. The Holy Father despised the bishop’s subtle way of demeaning those around him, including the pontiff and his staff, when either Otto or Adelaide was present. What most annoyed Pope John was Liutprand’s insistence on attending the sessions about Magdeburg. In order to arrange intimate sessions with Adelaide, the pontiff scheduled conflicting meetings that allegedly required Liutprand’s unique expertise. The journal speculated that Liutprand was envious of Adelaide’s time with the pontiff. Still, Octavian thought that most men were jealous of him. He may have been right. I certainly envied his lifestyle.

Pope John was definitely not even-handed in his dealings with Liutprand, whom the king employed as diplomat, historian, and trusted adviser. The pontiff belittled Liutprand at every opportunity. For example, he pointedly asked the king whether the ceremonies involved at Liutprand's consecration as Bishop of Cremona included anything like the traditional papal ritual that employed the sella stercoraria. When informed that no such ceremony was performed in Cremona, Pope John sniggered and remarked that he had suspected as much.

When Otto departed from Rome, the bond between the empire and the papacy was as strong as ever. Otto demonstrated his respect for the agreement by using his army to expel the forces of Berengar and Adalbert from the traditional papal territories. This was greatly appreciated by the Roman people, as was the subsequent departure of the Germans.

My recollection is that the story of Otto’s journey to Italy was related in one very long entry that ended with a triumphal procession through the city. Roman citizens, according to the journal, were thrilled that their young leader had persuaded this powerful barbarian both to protect the city and expand its territory. According to the journal, John's father Alberic, although ruthless to his enemies, brought decades of peace and prosperity to Rome. His son seemed capable of even greater things. Pope John himself was ecstatic at the outcome of the emperor's sojourn in Italy. He boasted that he ruled over more territory than any previous pontiff. He considered himself the youngest and the greatest of all popes, the Alexander the Great of the papacy. I was a bit surprised that he had heard of Alexander.

Success whetted Pope John' appetite for diplomacy. The subsequent entries devoted nearly as much ink to his efforts to forge relationships with other sovereigns as to his amorous encounters. His aunt disappeared from the journal's pages.

The region of the world that attracted most of the pontiff’s attention was Poland. At the time I was completely ignorant of that strange and distant land. Pope John dispatched Egidius, the Bishop of Tusculum, to improve the Holy See’s understanding of problems involved in spreading Christianity to the Polish heathens. Evidently the reports that Egidius filed were quite unsatisfactory. The youthful pontiff even considered journeying to Poland to manage the situation in person.

A little more than a year later, however, the tone of the writing darkened. Pope John learned from envoys that the emperor planned another excursion into Italy, but this time his mood was foul. The Holy Father was convinced that Otto intended to replace him with someone whom he could control. The pontiff therefore warned the emperor that he would be excommunicated if he did not turn back, but the threat failed to slow the the imperial army as it approached Rome, Pope John and his retinue hastily beat a retreat to Tivoli and eventually even withdrew to the island of Corsica.

This outcome obviously exasperated the Holy Father. The journal’s descriptions of various people in the imperial party were peppered with expletives and imprecations that shocked and embarrassed me. Pope John considered Liutprand, who evidently still enjoyed the emperor’s ear, the instigator of his difficulties.[27] Papal spies had reported that the bishop had spread slanderous accounts of the pontiff’s duplicitous and scandalous behavior. Evidently the bishop had cultivated more allies in Rome than the pontiff and his staff had detected.

The journal cast aspersions on a council in Rome called by the emperor. Many local bishops had willingly attended. The council found the absent pontiff guilty of a list of crimes and judged him unfit for his position. It therefore replaced him with a layman named Leo.[28] The exiled Pope John swiftly issued an edict ruling that, since only the pontiff himself had the right to convoke an ecumenical council, the unauthorized assemblage was bogus. Pope John had been much too clever to cede a privilege of that nature to anyone. He issued papal excommunications to all participants in the synod.

When they learned that Leo had been invested as pope, the Roman people, or at least a good portion of them, rose up in revolt and assailed Castel Sant’Angelo. The result was a massacre in which loyal Roman citizenry proved no match for the emperor’s well-trained, well-equipped, and disciplined army.

Pope John rejected the strategy of moving against the emperor directly; he patiently plotted in absentia knowing that time was on his side. Eventually, deteriorating conditions in the homeland compelled the emperor and his army to return to Germany. Their departure provided an opportunity to foment a second revolt led by the pontiff himself. The pretender Leo fled for his life, and the pope’s men never discovered his hiding place. On his return Pope John convened another synod that overturned everything that the previous one had implemented. He found it amusing that the same bishops and clergymen who had judged him as a dastardly felon a few months earlier now pledged their wholehearted support.

More than half of the last scroll was blank. The journal abruptly ended shortly after Pope John had regained his throne. At that point he was still in his twenties. It seemed clear that great things might await him and the city of Rome, if he could induce the emperor to remain north of the Alps. I knew much more about him than I did before, but I was frustrated that I never learned the end of the story. When I asked my elders about his pontificates, they told me nothing of his fate beyond the terse statement that the Lord had struck him down for his sins.[29]

[1] March 26, 1026. The Iron Crown was used by the Lombard kings of the seventh and eighth century. When Charlemagne vanquished the Lombards, he seized the title and the crown from them. By the eleventh century it was associated with the title of King of Italy, although large parts of the peninsula, including Rome and the Papal States, were ruled by others.

[2] On Christmas day of 800 in St. Peter’s.

[3] This phrase indicates that he was on a pilgrimage.

[4] On ceremonial occasions emperors traditionally held the reins of the pope’s horse as a strator might. This was considered an act of humility and obeisance.

[5] This probably refers to thin wooden planks covered with wax.

[6] “Peter’s Pence” or “Romescot” was a traditional payment from the Saxon people to the papacy.

[7] After the synod the emperor led a rapid excursion into southern Italy followed by a forced march back across the Alps to escape the diseases that often prevailed in medieval Italy in the summer months.

[8] The second king was most likely the aforementioned Rudolph, who was related to Gisela.

[9] The author's counting appears not to include the ground floor.

[10] Tiberina is an island in the Tiber River. Bridges have always connected it to Rome and to Trastevere. It has housed a medical facility since ancient times.

[11] Unfortunately, the author never wrote about payment of the debt to his friend. It would be enlightening to learn how a young man obtained so much gold.

[12] The Latin word used was “Princeps”, which has a stronger meaning than “prince” today. Octavian probably had a great deal of authority in the city.

[13] Most modern sources cite as Octavian’s mother Alda of Vienne. She reportedly had a brother named Lothar, but I found no mention of any sisters.

[14] The Roman Senate had been dissolved for centuries. The exact function of Senators in the eleventh century is unclear.

[15] Agapetus II was pontiff from 946 to 955, but Alberic ruled Rome and the Patrimony.

[16] Pope John XI was pontiff from 931-935. For much of that time he was held captive by Alberic, Octavian’s father. Alberic and John certainly had the same mother, Marozia, and they may have also had the same father.

[17] Pope John XII ruled from 955-964.

[18] The popes resided in many different buildings over the centuries, but the Lateran Palace donated by Constantine has nearly always been one of the principal buildings used by the Holy See. It is adjacent to St. John’s Basilica, the pope’s cathedral.

[19] The word “cardinal” by itself was not used as a noun to describe a clergyman until centuries later.

[20] Berengar II and his son Adalbert reigned as co-kings of Italy beginning in 950. From 952 on they were vassals to King Otto of Germany, but they retained their crowns. Then, as ever, Italian politics was very complicated.

[21] Otto I enjoyed a thirty-seven year reign as King of Germany, beginning in 936.

[22] In fact, she was canonized by Pope Urban II in 1097, and she is venerated as a saint in both the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox Churches.

[23] At the time that he was crowned as emperor, Otto was nearly 50. Adelaide was almost twenty years younger.

[24] They had four children together, but none in the seven years before the coronation.

[25] Adalbert was Berengar’s son and ruled Italy with him.

[26] St. Adalbert of Magdeburg was canonized by Pope Sylvester II in 999.

[27] In fact, Liutprand’s Historia Ottonis sive Liber de rebus gestis Ottonis imp. an. 960-964 is one of the very few available sources of first-hand information about this period. Most historians think that its purpose was as much to praise the emperor as to record the facts.

[28] This man became Pope Leo VIII after the death of Pope John XII. Leo is for some reason considered an antipope in his first reign. The remarkably similar pontificate of Sylvester III (Chapter 9) is officially considered legitimate.

[29] The Catholic Encyclopedia concluded its entry on Pope John XII with these sentences: “John died on 14 May 964, eight days after he had been, according to rumour, stricken by paralysis in the act of adultery. Luitprand [sic] relates that on that occasion the devil dealt him a blow in the temple in consequence of which he died.”