Chapter 5: Sin, Confession, and the Beginning of a Long Penance

I have always felt boundless admiration and respect for my older brother. He epitomized virile qualities that I esteemed above all others. I loved him profoundly, and I envied him with the same fervor. Admitting that the most reprehensible deeds of my life indirectly involved Gregory brings me shame. I have committed many sins. The goal of this work was to provide as complete and accurate reckoning of my thoughts, words, and deeds as I could. Recalling this set of events to mind evokes extreme anguish in me, but the importance of my objective impels me now to set my pen to parchment. Tears of shame cascade down my cheeks. I can only hope that my frank admission of such dreadful failings may convince readers that my dismissal of other outrageous slanders propagated by my enemies is justified.

Fr. Lawrence customarily retired to the monastery for important holidays. I spent these periods with my family in Tusculum, where I resumed my habitual strolls through the countryside. Although my destination was usually the same old shed, I carefully varied my routes. I never set out in the same direction on consecutive visits, and I would occasionally stop to examine some flowers and, while so engaged, to listen for footfalls.

As my family gathered in the estate in Tusculum on one fateful Easter weekend, only my brother Gregory was absent. Pope John had dispatched him upon a mission to four towns near the Adriatic coast. The nobles and clergy there needed a forceful reminder of their financial obligations to the Holy See.

As was my custom, I excused myself after a particularly delicious Easter dinner. The bright sun hinted of the coming summer. I ambled around the countryside talking to animals. I inspected plants for a while and then headed toward the shed. Before entering I glanced around to assure myself of solitude.

I settled myself on the rags and blankets on the floor. I then began the rites that had proven so effective in warding off the devil’s assault. I was well into the most intimate phase when to my shock and dismay the door burst open and a familiar bird-like voice caused me to try to conceal my gorzo, which had at that point very nearly reached its maximum size.

“Well, what have we here?” asked my sister-in-law, Costanza. “No, no. Do not cover it up. This is exactly what I came to see. Just sit back and relax. Let me show you the purpose of that thing.”

Shame and shock overwhelmed my intellect, and it proved incapable of providing me with a sensible course of action. The tiny portion of my mind that was still operational failed to produce words for my mouth to vocalize. Instead, what emanated from that cavity was the guttural noise of a trapped animal. With a mischievous leer on her face, Costanza used her left hand to push my head back onto the blankets while she loosened my garments with her right. I was as incapable of resistance as if a man twice her size had been held me down. I felt paralyzed.

“Ye gods and fiddlefish! I have never seen such a thing. Are you sure that Gregory is your brother? Never mind. Just keep still and do as I say.”

She seized my gorzo, an act that caused it to spring back to life.

All of my willpower was required to prevent a horrible accident. She clamped her mouth on mine and inserted her nimble tongue well within. No memory of the rest of that day remains in my mind, or, rather, the recollections of a cascade of novel sensations—tastes, smells, touches, sounds, sights, and the other more mysterious effects of this encounter—to this day remain incredibly strong, even overwhelming, although imprecise and muddled.

At some point Costanza abandoned me in the shed. I do not remember the details of her departure, but I vaguely recall making my way back to the palace. I certainly entered alone. By then it was almost time for supper, and a few people had noticed my extended absence. My thoughts turned to the monks' vows of chastity. I concluded that they all must be insane to forswear what I had just experienced. Could they fathom what they were missing?

I must emphasize that this startling incident was neither repeated nor mentioned, and its effects seemed isolated to the two participants. I continued to visit the shed, but I redoubled my precautions to ensure that I was truly alone. Indeed, throughout the rest of the holiday I continued to battle Satan there, but I encountered neither Costanza nor anyone else. After the holiday I returned to Rome and resumed my studies. The next major holiday, Pentecost, was likewise uneventful.

Everyone knows that the summer heat in Rome is often unbearable. Every year Fr. Lawrence closed the school for three weeks so that the students could celebrate the Assumption[1] in more healthy and comfortable settings. I returned to Tusculum and reestablished my routine there. On the eve of the feast day I received a message from my older brother that he wished to talk to me in his quarters. I dared not ignore his summons.

Gregory stated that for the first time ever he needed my help. Needless to say, a flood of emotion engulfed my heart and clouded my mind when he disclosed that the source of his problems was his wife. As I sat nervously across from him, my brother explained that over the previous few months Costanza had repeatedly complained of her confinement within their palace while he was away on assignments. He had attempted to address the issue by providing her with servants and companions, but she insisted that her problem was less loneliness than boredom from lack of mental stimulation. The day before our meeting she had issued an ultimatum. He must allow her to expand her horizons, either by letting her ride with him on his adventures in the papal territories or by providing for her education, preferably by the monks in Grottaferrata.

“Theophylact, no woman, least of all a refined woman of Costanza's stature, should be exposed to what I witness every day on assignments in remote regions. The conditions in which we live are filthy and unhealthy. The troops are coarse and unpredictable. Maintaining the morale of my men is one of my most important obligations. Sometimes, it helps to relax the reins a little, so to speak, and I have no doubt that Costanza would be appalled by their beastly comportment. And, of course, if anything happened to her, well, I don't want to think about it. Her participation in these missions is absolutely out of the question.

“The other alternative seems just as bad. I would never consider turning a beauty like her over to those randy monks.” He must have noticed the shock on my face. “Oh, I know, some of them are no doubt trustworthy and sincere, but everyone has heard stories of monks in rut. It cannot be healthy for all those men to live together away from women. I can only imagine what transpires behind their walls, and I have no intention of sending my lovely wife in there to find out.

“So, I am turning to you. I know that I can trust you, both because of your inherent nature and because if you ever turned on me, you know that I could—and would—beat you to a bloody pulp without a second thought.” He grinned at this comment, and I tried my best to match him. “You know almost as much as those cloistered freaks, maybe more in some respects. I want you to spend a little time with Costanza. Teach her to read and write. She also indicated an interest in learning Greek, your specialty.

“You will continue your classes with Fr. Lawrence, of course. I would never interfere with your education. It is too important. However, when you find yourself here in Tusculum, I hope that you can schedule some time with Costanza. You might even enjoy it. She is very sweet, and she has a good head on her shoulders.”

I wrung my hands and silently prayed for inspiration. No reasonable excuses for refusing my brother’s request came to mind, but even a youth as naïve as I could recognize the potential for disaster if I agreed. “But I have never taught anything to anyone,” I stammered. “I frankly doubt myself capable of imparting knowledge to others. I would not know where to start. Brother Clement is certainly more qualified than I. Surely you could trust him.”

“The last person I want lurking around my wife is that weird Clement character. Something about him makes me bristle. Look, Theophylact, I am in a tough situation here, and you definitely owe me. At least try it. Get Clement to help you put together a lesson plan. Then contact my wife and set up mutually convenient times for tutoring sessions. I am confident that you can do this. She is bright for a female. You might even learn something from her.”

Thus began my unexpected and dreaded stint as Costanza’s tutor. I soon discovered that, unbeknownst to my brother, she already knew how to read and write Latin fairly well. She therefore could demonstrate considerable progress rather quickly. When Gregory was in the palace, she was very circumspect. The most affection that she ever showed toward me was a light tap on my hand. Even that sent shivers up my spine and brought my gorzo to attention despite the usual precautions. After any contact all my will power was required to maintain my equilibrium throughout the lessons.

Costanza delighted in arranging public recitals of what she had supposedly learned from my tutoring, and she always insisted that Gregory and the rest of the family attend them. Everyone was impressed at how quickly she had absorbed so much learning. My family naturally attributed much of her progress to my putative skill as an instructor. I knew better, but I felt no need to disabuse them of their misguided assessments.

When her husband was away from Tusculum, she dismissed all but her most trusted servants, and our roles were reversed. She became the teacher and I the student. Our primary subject was anatomy, and she introduced me to her entire body, a few important parts of which I did not even know existed. I was a good student, too, at least as good as she was. I even amazed my tutor a few times with techniques that I had gleaned from Pope John XII’s journals. Unlike Costanza, however, I never felt compelled to display in public the techniques that I had perfected in private sessions. Nevertheless, I was proud of my newly acquired knowledge and skills and eager to put them into practice in a non-academic environment.

For over a year our mutual education exchanges continued unchecked whenever I spent a few days in Tusculum. On my return from Rome for the next Michaelmas,[2] however, I was greeted by Brother Clement as I was about to stable my mount before entering the family's villa in Tusculum. His tone was amicable, but the look on his face was grim. “Theophylact,” he said, “Before you put your horse away, you should ride over to the abbey. Hegumen Bartholomew needs to speak with you. It is important.”

Hegumen Bartholomew had been a disciple of Nilus, the saintly founder of the abbey in Grottaferrata. I had seen him occasionally, and I knew that he had an unblemished reputation for both sanctity and forthrightness. I had never had any dealings with him. I could not imagine why he would wish to speak with me or any other teenager. I guessed that he might want to encourage me to join his order. After my experiences of the previous year or so, there was no chance of persuading me of the value of a committing one's life to avoiding its most pleasurable aspect. During the preceding months my feet had scarcely touched the earth when I walked.

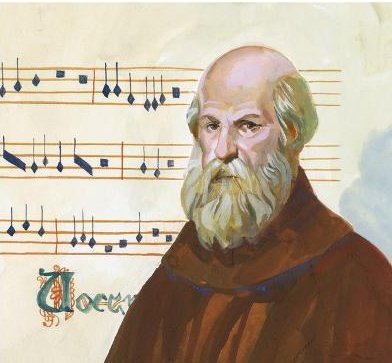

A monk led me to the hegumen’s cell. I could hardly believe that the great man lived in such squalor. His abode contained a straw mattress, a stool, a table, and almost nothing else. It was large enough for those few objects, but little space remained. His robe was more tattered even than Brother Clement’s. His massive lined forehead was the first feature that anyone noticed. His beard was poorly trimmed, ink stained his fingers, and grime was visible beneath the nails. I found him absorbed in the act of humming softly to himself and recording notes on his charts.[3] He lay down his pen. In a stern but soft voice he offered me the stool and dispensed with the customary niceties. “Theophylact, my son, sit. We have much to discuss.” He sat cross-legged on the mattress so that I was in the uncomfortable position of gazing down at him.

“To begin with, I know about what you and Costanza have been doing. Do not prevaricate or make excuses. It will only provoke ire, and it is extremely important that we both maintain composure. There are things that you need to know lest you destroy your own future and compromise the future of the entire Church in one feckless blow.”

I was dumbstruck. It had never occurred to my ignorant juvenile mind that anyone, let alone the hegumen, could have discovered my involvement with Costanza. At first I tried to remain calm. Perhaps he was only talking about the Latin and Greek classes in which I served as teacher. Maybe he suspected me of trying to show off my limited abilities at the monastery's expense. Presumably tutoring generated income. It seemed inconceivable that he knew about Costanza's pedagogical efforts. How could he? No one else was ever present.

“But, …” I started.

“Costanza herself came here and spoke with me. She is with child, Theophylact, and she thinks that you are the father.”

I fell from the stool. I understood that intercourse was associated with procreation, but I just assumed that Costanza would account for it. It was her plan. I was too ignorant to make suggestions or even to pose appropriate questions. She seemed to be such a wise person that it was inconceivable that she might let this happen. The hegumen reacted to the distraught look on my face as I regained my seat.

“Now calm down, boy. This is not a disaster. I recognize Satan’s handiwork in your behavior, but it would not be sinful[4] to terminate the pregnancy at this stage. So I have advised Costanza, but she insists on bearing the child. I hope that others can be more persuasive. Women in her state sometimes forfeit what little rationality the Lord originally endowed them with.”

For the first time I tried to imagine what Costanza must be experiencing. I suddenly felt a wave of compassion and concern for my sister-in-law, but when I attempted to visualize her conversing with the hegumen, I could not help it; my gorzo became aroused—yes, even in the holy man’s presence! I beat my head hard against the stool in hopes of stifling the disturbance before he noticed.

With all the mental faculty still at my disposal I imagined how this discovery would affect my life in Tusculum. I foresaw nothing but tragedy. I envisioned my brother hunting me down and slaying me with the patience, persistence, and deadly intent of Odysseus after he had arrived back in Ithaca. He would find me no matter how well I hid or how fast I rode. After he exacted his revenge, he would be forced to pay the price for his vengeance, for no man who murdered his brother—even a despised cuckold—could maintain his lofty standing in the community. I would be a corpse, but I would still be the lucky one. The mental image of my brother wringing my neck did not soothe my spirit, but it did have the salutary effect of shrinking my gorzo.

I sat on the floor cradling my throbbing head in my hands. I made a desperate plea to God to take my worthless life between His omnipotent thumb and forefinger and snuff it within the next few moments. I begged Him to eradicate my pathetic existence before I drew more people into the disastrous quagmire of my life. That would be merciful and just.

A thought sprang into my mind, and I embraced it as God’s response to my prayer. I gazed meekly up at the hegumen and spoke, “Lord hegumen, I desire with all my heart to avoid these sinful occasions in the future, but I lack confidence in my ability to battle Satan. I know the story of St. Ignatius, the eunuch and Patriarch of Constantinople. Could I not be rendered like him to obstruct this pathway from the devil to my soul? I would willingly submit to anything that assists me in this battle. I cannot bear to bring more shame on myself and my family. I can accept the pain and humiliation. Please. I cannot go on like this.”

My request definitely startled the hegumen. He pondered for a few heartbeats before he replied, “I judge your request to be serious, and I respect you for it. It reveals a certain amount of character. However, you seek a boon that no one, not even the Holy Father, can grant.”

He paused to consider how best to steer the conversation. “I have been assigned the task of disclosing the Lord’s plan for you, Theophylact,” the hegumen continued in measured tones. “A great deal is ordained, but your present course of behavior could very well upset the careful planning and undermine the tremendous good that has been accomplished by your two uncles, your father, and your brother in the course of your lifetime. We would be back in the perilous position in which we started or worse. You understand that we cannot allow that; do you not?”

He did not await my response. “As you undoubtedly realize, prior to Pope Benedict VIII’s pontificate, management of the affairs of Holy Mother Church had fallen into the hands of scoundrels and ne’er-do-wells. Preceding pontiffs used their sacred office primarily to enhance the wealth and status of their families. Rome degenerated into a lawless community, and the Church’s influence throughout Italy fell to the point where the Saracens established colonies on our beloved peninsula. Their troops were just outside of Rome!

“Perhaps the worst facet of the crisis was that some very ambitious monks—no followers of St. Basil, mind you—have used the situation to make a persuasive case that the papacy was responsible for the deplorable situation. Their proposed solution, as you might imagine, was to take over the administration of the Church themselves. The label that they used to mask their ambition was ‘reform.’

“Your family and its allies have sworn to restore the Church and papal territories to the days of glory and progress. In the last fifteen years the Holy Father and his brothers have advanced the goals to which we are all firmly committed. Romans—at least for the most part—respect the Church again. The Saracens have been checked. That battle is by no means completely won, but we now seem to have the upper hand. The rule of law has been reinstituted. Construction of magnificent churches and monasteries has been undertaken in the Lord’s name. A solid relationship has been established with the emperor and various kings. Things could be better, but everyone is aware that they could be much worse.”

The hegumen stopped and took a sip from his wine cup.

“I know all of this, …” I managed to whimper softly.

“I must now describe your role. That is what you long to know, is it not? The answer, Theophylact, is that you are destined to follow your Uncle Romanus onto the Throne of St. Peter. At the death of Pope John, which we all pray lies many years in the future, you will become Supreme Pontiff of the Church, and your brother Gregory will eventually succeed your father as manager of the affairs of state. This order of events was decided years ago. Your training and education has been designed to help you deal with the responsibilities of the papacy just as Gregory has been groomed for his duties.

“You have personally witnessed the papal investiture ceremony. If you paid attention, you surely realize that under no circumstances could a eunuch become pope. That alone is sufficient to disqualify your request. There are other reasons.”

To state that these words stunned me would be a grotesque understatement. The idyllic world that I knew so well collapsed around my shoulders. The detritus in which I found myself buried up to my ears exceeded comprehension. I wallowed in despair and disbelief.

“But you must realize that I am too puny to fight the demon by myself. Could you arrange for an exorcist to expel it from my body and thereby free me to do the Lord’s Will?”

“If we suspected that a demon was actually responsible, we would indeed try that. However, your behavior has none of the characteristics of a demonic possession. What you have faced, Theophylact, is essentially the same temptation that every healthy young man has faced since the serpent introduced Eve to the fruit in Eden. You must learn to control your body. The battle will be difficult at times, but you must prevail. We have determined that it might be helpful for you to spend time away from Rome in order to discover what is required of a young man who will someday be Vicar of St. Peter.”

With his eyebrows the hegumen made a slight gesture that caused the lines in his forehead to disappear for an instant. “So, the following will occur, and it must begin before another day passes. You will proceed to the Holy Father’s chambers in your family’s villa forthwith and confess your sins to him. You need not feel ashamed or embarrassed, at least no more than you do now. His Holiness has been apprised of this tawdry affair. As penance he will mandate a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. While there you will be expected to retrace the Lord's steps. Our hope and expectation is that this journey will instill an understanding and appreciation of your special role in the Divine Plan, which will in turn inspire a return to acceptable behavior.

“Your departure will be officially announced, of course, but no details will be disclosed to the public. The emphasis will be on the spiritual aspect. Penance will not be mentioned. In your absence your sister-in-law’s situation will be addressed. Do not concern yourself about it. Let me say that again. Do not concern yourself about it.

“Your friend Gerard has been ordained as a deacon in our order. We have arranged for him to accompany you on the pilgrimage. His assignment will be to guide your spiritual quest to regain your former status. Gerard is a resourceful young man, and we have confidence that he can steer you from trouble. I want to impress upon you the seriousness of the undertaking. We all expect you to return fully prepared to accept your responsibility, weighty as it is.”

The hegumen waited for a few heartbeats to gauge my reaction. I sat in stunned silence.

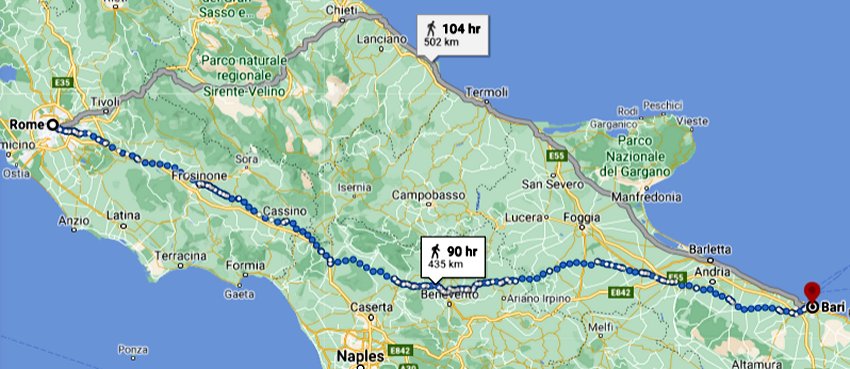

“The two of you will travel overland to the seaport city of Bari. Thence passage has been arranged for you on a Venetian ship bound for Antioch. There you will endeavor to attach yourselves to a larger band of pilgrims en route to the Holy Land. When you reach Jerusalem, you should seek out the patriarch, whose name is Nicephorus. He will provide you with a letter addressed to the Holy Father. You will bring it back with you.

“Do you have any questions?”

If my mind had been functioning properly, a hundred queries would surely have tumbled from my mouth. The hegumen had ordered me to abandon my comfortable life in favor of an adventure of unspecified dimensions. In fact, however, I sat sobbing in disbelief, fear, and horror. I could not imagine how I could face the rest of the day, much less the pilgrimage that he had outlined. This reaction evidently satisfied he hegumen. He dismissed me.

Brother Clement escorted me to Tusculum. I was too stunned and dejected to do more than sit in the saddle. After we dismounted, Brother Clement pointed me toward the family’s villa. We avoided the rest of the family as he brought me up to the Holy Father’s private quarters and abandoned me at the door. I waited for a few heartbeats to give God a chance to exterminate me as he did Lot's wive. I entered and prostrated myself on the floor to kiss the pontiff’s slipper. Then, still sobbing and lying with my face to the floor, I confessed my heinous sins.

His Holiness was stern but gentle. He ordered me to rise to my feet and showed me to a chair. He stated that he appreciated the difficulty of learning to be a responsible young man. Then he emphasized that Satan was likely to continue to seize every opportunity to divert me from the path of rectitude. I must be ready to confront him at all times and in all places. Unfortunately, he offered no specific suggestions as to how I might win these battles.

Pope John then granted me absolution and explained that it would take effect as soon as I completed the pilgrimage to Jerusalem, as the hegumen had foretold. The conversation lasted a long time. He was a very thorough man, and he undoubtedly provided me with detailed instructions for the pilgrimage, but my mind and spirit were still incapacitated by shock, shame, and remorse. I distinctly remember his tone of voice but scarcely any words. My heart felt gratitude for the opportunity to avoid the questions and shocked glances of my beloved friends and family, but my mind still fervently wished that the almighty Father would put an end to my miserable existence before I brought more shame and sorrow into their lives.

Upon descending from the pontiff’s chambers I learned from my mother that both my father and my older brother were absent from Tusculum. Although she said nothing of my misconduct as she helped me pack for my journey, her lovely face betrayed both her disappointment and her love. I can still recall the sight of a tear escaping from her blinking eye and trickling down the smooth curve of her cheek. She had ordered a sturdy mule to be brought from the stables to haul our equipment. At the first ray of dawn we loaded it with my gear. The last sight of my mother will remain scorched into in my memory as long as it can function. One hand grasped the other at the level of her waist, and she pressed them together tightly in frustration and worry. Her hair was slightly disheveled, but it glowed in the morning light. Tears streamed unchecked from her beautiful eyes.

My mother died while I was on the pilgrimage, and I will always believe that my reckless behavior killed her or at least hastened her demise. The Lord has officially forgiven me, but I will never grant myself absolution for that effect of my great sin.

I had been instructed to meet up with Gerard at the “Quo Vadis” sanctuary[5] on the Appian Way, but I did not see him when I arrived there. As pilgrims often did, I stopped inside for a period of prayer and meditation in hopes of gaining inspiration and courage for the long journey before me. Since my meeting with the hegumen my thoughts had focused on my own misery and that of my family. For the first time Gerard’s disability sprang to my mind. I realized that the journey would surely be insuperably difficult for a man with his ailment. Walking to Bari would surely require a fortnight or more, and I had no idea what to expect thereafter. I realized that I should have asked my mother to provide a horse for my lame friend. My transgressions were about to cause a person close to me to suffer months of anguish.

After my mind had been submerged in such thoughts for some time, a deacon glided up to me and addressed me in a gentle voice filled with calmness and sincerity. “My son, I saw that you were deeply in prayer. Have you completed your pilgrimage, or are you about to depart?”

“Reverend sir, I depart this very day, and I have a very long journey ahead of me, for my destination is Jerusalem itself.”

From the deacon’s mouth a gruff and sharply familiar voice emitted the following: “Well, that is not nearly as far as hell, which is where you should be going.”

I looked at the deacon more carefully and realized with a start that he was actually my friend Gerard. I had recognized neither his voice nor his gait. His limp seemed to have completely vanished as he escorted me outside. The features on his face were familiar, but somehow seemed arranged much more pleasantly than I remembered.

“We are pilgrims,” he announced in Gerard’s voice. “And we must at all times look and act like pilgrims.” We exited the chapel together.

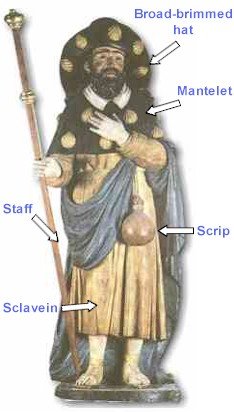

He showed me two long brown tunics that he had brought as well as scrips to strap on our backs and broad-brimmed hats to shield us from the sun. Our feet were protected only by thin sandals. We each bore a staff with an iron tip. After he made me unstring my bow and strap it on the mule, he seized my sword, wrapped it in rags, and affixed it to our beast of burden in such a manner that it was concealed and impossible to draw quickly.

I immediately objected, “But we have no access to our weapons. How will we fight highwaymen like the ones who waylaid the visitors from Constantinople? Surely the bandits will gasp in delight when they see us strolling down the road with nothing but sticks for defense.”

The deacon clasped his arm around my shoulders and answered in the friendliest tone imaginable. “The staffs are part of the pilgrim's attire. Their purpose is to help with balance in difficult terrain. The ambush in Rome is not analogous to our journey. In the first place, the Romei were traveling at night by secondary roads. Our route follows the principal highway in the region, and we will be abroad only in sunlight. Moreover, most of the area through which we will be traveling is regularly patrolled by the Greek emperor’s troops. Bandits allow them a wide berth. Finally, and this is important, the last thing that we want on this journey is to engage in a fight. If someone or something evil or dangerous appears, you must follow my lead and do what I say, agreed? That is what I am being paid for.”

The whole speech, which I have condensed, astounded me. It probably contained more words than my friend had spoken in the years that I had known him. I was most surprised by the last few. I assumed that Fr. Lawrence or the Holy Father had ordered him to join me and that he felt a duty to comply, or maybe simple amity may have motivated him. I never learned how much he had been offered to escort me or who paid him.

Having donned our tunics, scrips, hats, and sandals, we inspected one another. The deacon seemed pleased with the results, and I was in no position to complain about appearances. The deacon’s voice assured me when he insisted that I looked like a proper pilgrim. He explained a few of the details. “For the rest of the journey you will be an acolyte named Longino, named for the Roman soldier who pierced the side of the Lord at the crucifixion. I am your cousin Agatho[6] the Deacon. My job is to help you complete the pilgrimage to test your worthiness for ordination into the priesthood. We both live in Tusculum, where our families have served the households of the counts for generations. That story is near enough to the truth that we should have little trouble maintaining it throughout our travels. However, you must pretend ignorance of the Greek language, and never mention those books that you have read. Above all, say nothing about your uncles, your father, or your brother. In fact, when anyone else is present, do not speak at all unless I indicate that you should.”

“But Gerard, …”

“Agatho the Deacon. Gerard is in Rome, and he will be difficult to find for a while.”

“Tell me what happened to your leg. Did a miracle-worker perform a healing ceremony? Did the saints intervene?”

He chuckled. “The person who intervened will never be called a saint. I assure you that I still have my limp, but I decided to retire it for the duration of our pilgrimage.”

He reached inside the folds of his garments and extracted an irregularly shaped stone with a width at its narrowest point of a fingertip. “With this in your boot, you would limp, too.”

I looked at him quizzically and tilted my head to one side.

“I discovered a few years ago that pretending to be someone else can be useful, but portraying another person convincingly is quite difficult. I learned that removing a disguise is much easier than donning one. So, a few years ago I decided to alter Gerard’s gait by giving him a limp. I probably could have faked it pretty well, but I dared not risk the chance that a clever rascal like the Toad might maneuver me into a situation that exposed the artifice. By keeping the rock in my boot I only needed to remember to wear it at all times whenever anyone else was present. You could recognize me from my walk from a hundred paces; am I right?”

“Until today. But the pain!”

“There are ways of dealing with pain. I already shared one with you when my machine decorated your arms in the watchtower. Besides, I have learned that life offers much that is well worth some discomfort. Do you not agree?”

As I write these words I can still remember how painful those cuts that I received in the watchtower had been even after my friend had treated them. Gerard’s tolerance for suffering must have been far greater than my own. “And your voice?” I asked.

“The voices require a good deal of practice. I work on them in the evenings.”

“Them?”

“Fifteen reliable voices are available, eleven male and four female. I associate each with an object or a set of objects. The one that Agatho is currently using goes with the hat and sandals, which I plan to wear from this point forward.”

“Which is your real voice?”

“They are all real. That is enough chitchat for now. Our journey will likely provide more than adequate time to explore the details of one another’s eccentricities and predilections. Let us now petition the chaplain for his blessing and depart.”

“The chaplain” was, in fact, the Holy Father himself, in the garb of a common parish priest. No one paid much attention to him. He cautioned us to be very careful, and he specifically enjoined me to trust Deacon Agatho’s guidance. Then the pontiff blessed us and pinned crosses on our tunics. We set off on the highway that had so often felt the impact of the footsteps of legions of Roman soldiers in the glory-filled days of the empire, the Appian Way.

During the rather steep climb that we faced after pointing our noses to the southeast, my friend quizzed me about my relationship with Costanza. I divulged as much as I could, including the contents of Pope John XII's journal, my embarrassing moments with the Greeks, the strange cook from Germany, the contrasting bits of advice offered by Brother Alexei and my brother Gregory, and the two refuges that I employed during my walks. Time after time he stopped abruptly and smiled. Once he even confided to me, “I misjudged you, Longino. I never suspected you capable of such things. You are truly an exceptional individual. In fact, I may need to reassess my view of humanity before our journey is ended.”

As always, the tone used by the deacon was friendly, but something ominous in the way that he said the word “exceptional” gave me pause. The eerie tone still reverberates in my memory to this day.

Deacon Agatho, as I soon came to regard him, inquired about the measures that I used to prevent the devil from taking over my mental faculties. He concurred with Gregory’s assessment of the usefulness of Brother Alexei’s prescription. He was less critical of my brother’s suggestion, but he claimed to know even better ways of dealing with the problem if necessary. “Follow my lead, Longino. The peasants in the hinterlands will probably expect two pilgrims such as ourselves to be devout and chaste. On the other hand, when we encounter people who have traveled extensively, their expectations may run in the opposite direction. Our objective will generally be to avoid attention by conforming to those expectations and avoiding fanfare.”

I explained that my brother’s approach seemed to work for me, until Costanza discovered my hideout. That prompted him to ask me “So, what are you going to do about her?”

I replied that I certainly would have no say in the matter. The hegumen told me that the issue would be addressed in my absence. He clearly ordered me not to concern myself with it. I admitted, however, that I was quite worried about my brother’s reaction. Furthermore, if I ever needed to interact with Costanza again, I would likely die of embarrassment.

The first night we camped not far from Tusculum. We then descended southward toward the sea. The fourth day of any journey on this road is the one most dreaded by Romans traveling on foot. Covering our faces to minimize the quantity of evil air[7] that entered our lungs, we hurried through the swampland. The sun prevailed that day, and we were fortunate to encounter air less fetid than anticipated. In addition, the annoying insects that thrived in this environment seemed more listless than expected. That night we lodged at an inn in Terracina. The innkeeper was expecting us. Evidently a messenger had been dispatched from Rome.

The next day we turned our noses inland and hiked through Capua. Eventually we crossed the Apennine Mountains and descended into the thriving town of Benevento. Thence we marched along Trajan’s Highway until we reached our destination of the port city of Bari. Etched in my memory of this long excursion are three days during which the skies erupted, and a chilling rain soaked our garments as we plodded along. I also remember that there were delightfully pleasant days, but I do not recall the precise number.

In any weather Deacon Agatho proved to be a much more sociable companion than the taciturn classmate of my long acquaintance. He especially seemed to enjoy discussing complex issues of faith and morality. He would often challenge me to take a position on some issue such as whether it was sinful for a poor man to rob a rich man. He would usually take the opposite position and outline arguments so cogent and persuasive that he would eventually convert me to his position. Then, when I was satisfied that my arguments had been indefensible, he switched positions and presented convincing ideas and illustrations to buttress my original position. Occasionally he would then mount a devastating attack against even those arguments. I began to doubt that my friend had a firm conviction on any subject. I begged him to tell me the truth. Both sides, I insisted, cannot be correct. He grinned at this, but he never directly responded.

Along the way we encountered several groups of pilgrims returning from Jerusalem. One was led by a prince from the Piedmont with his wife and young son. They resembled none of the other groups, who wore the traditional pilgrim's garb. The prince and his family dressed elegantly and were mounted. They were surrounded by an armed escort of ten or so footmen.

The prince enthusiastically disclosed that the sublime experience of following in the Lord’s footsteps had changed his life. He planned to take his wife and son back to his estate. He then hoped to devote the rest of his life to the Lord by cloistering himself in the great monastery at Cluny beyond the mountains. I admired and was inspired by this gentleman’s manifest devotion. Deacon Agatho addressed him in a voice that exhibited the same level of respect. After we had parted ways, however, he castigated me for praising the prince. “That fellow is a selfish jerk.[8] He plans to cast out his family even though they did him no harm. How does he expect them to get by on their own? And if he thinks that he will find God in that massive fortress in Cluny, he is as stupid as he is thoughtless. If you ask me, Longino, there is a much more likely explanation.”

I recognized the cynical but familiar sound of Gerard’s voice that had replaced the deacon’s in the last sentence, but I could not guess his meaning. He read the frown on my face as a question and resumed speaking in the deacon’s soft friendly tones: “The devil tempts a certain portion of male humanity in a different way from what you have experienced. In your short life you have already become excited beyond control because of three women, correct?”

“In truth, more than three.”

“Well, then. Some men are similarly excited, but not by women. Instead, they find themselves irresistibly drawn to other men. Yes, it is true. Some say that the attraction may even be stronger than the forces that have launched your own foolishness.”

His disclosure astounded me. “What are you saying? I have never heard of such a thing. A man attracted to another man? Do all such deviants reside in the Piedmont?”

“You almost certainly have encountered some of these men. They don't wear sashes or special hats to identify themselves. A good number are monks. The Church has long tolerated their aberrant behavior as long as they followed the norms of the Church and society when they ventured forth from the cloister. The authorities tend to look the other way as long as no one makes an uncomfortable scene. I would wager that somewhere on his pilgrimage a foreigner introduced our prince from the Piedmont to a degree of pleasure that he had never before realized was possible. He probably intends to join the monastery to make sure that he has a reliable way to satisfy his appetites.”

A pleasant aspect of the journey across the Italian peninsula was that it provided enough time to think deeply about experiences like this one. I certainly learned to be more skeptical of my first impressions of people.

On the road just west of Benevento we encountered a group of pilgrims from Pisa who were returning from Jerusalem. They bore a small bag of sacred relics purchased in the Holy Land. I respected the sacred items for the devotion and holiness that they represented, but they held scant fascination for an energetic young man on the cusp of his first adventure. Deacon Agatho, on the other hand, pelted the pilgrims with inquiries concerning the people who bought and sold these items in Jerusalem. They mentioned an abbot named Richard from beyond the mountains who seemed obsessed with collecting such relics. The deacon asked for details of how the abbot had originally obtained his relics, but the pilgrims denied such knowledge. I remember noticing that for an instant a scowl darkened the deacon’s face.

As we neared the village of Andria we encountered a remarkable group of pilgrims as dusk approached. They were all busy gathering and stacking hay in a barn adjacent to a small inn. Their leader, a hatchet-faced monk named Brother Honorius, emerged to greet us. He aggressively questioned us about our attire and our mule. “You two appear to be dressed as pilgrims, but your sandals and your beast betray your intent. Be gone. Do not attempt to corrupt my followers. Our group has completed a true pilgrimage, which required us to discard all possessions and walk the entire way barefoot.”

Deacon Agatho hastily fashioned this humble reply: “Never would we dare to impugn your motives or behavior, good brother. We applaud your Christian zeal, and we respect your judgment. My cousin Longino and I are indeed bound for Jerusalem on a mission assigned by the Holy Father himself. He entrusted us with letters and precious gifts for the patriarchs of Antioch and Jerusalem.”

This puzzled me. No one had mentioned precious gifts, and I had noticed nothing in our gear more valuable than my sword. I was about to ask about these claims when I remembered my instructions. I looked at my feet and kept my mouth closed.

The monk’s tone revealed nothing but disdain. “If you are truly on a sacred pilgrimage, then you must proceed as legitimate pilgrims. That means that you must immediately remove your sandals and donate them to the poor. As we have recently completed our pilgrimage, and we have no possessions, it behooves you to leave them with us.”

The deacon quickly bowed his head in agreement. “You may certainly assume possession of our sandals, and we thank you for outlining the rules and customs of pilgrimage. I assure you that our transgressions stem from ignorance, not ill intent.”

Agatho promptly removed his sandals and handed them to the monk. With a gesture he indicated that I should do the same. Brother Honorius inspected the sandals and then put mine on his gnarled and calloused feet. The other pair he stored in his scrip.

“Very well, and what are these gifts that your mule is bearing?”

“All that we know is that they are heavy, and each is in a plain wooden box sealed with the Holy Father's mark. We were ordered to show them to no one lest we forfeit our immortal souls. I should not even mention them, but you are clearly sincere and devout servants of the Lord and therefore worthy of trust.”

“And why would the pontiff assign such an important mission to such a pair when he could send archbishops or cardinal-bishops with armed escorts?”

“He did not say, and we dared not ask. Our family has always lived in Tusculum, and we have worked for Pope John and his kin for many decades. Perhaps he felt that he could trust his fellow Tusculans more than strangers. Even clergymen of lofty rank can give in to temptation. Perhaps he wished not to draw undue attention to the gifts. I merely speculate; we are not privy to the Holy Father’s motives, only to his instructions.”

The deacon continued: “Is your group staying at the inn? I hope that there are sufficient foodstuffs and bedding for all of us.”

“Your ignorance astounds me. Pilgrims have little use for inns,” snorted Brother Honorius. “When their feet can carry them no further, they hug the dirt, grass, and stones that the Lord provided and gather whatever respite that He deigns to provide. We negotiated with the innkeeper this morning to exchange our labor for a sampling of his porridge, but he demanded payment in coin for the use of his beds. We have none.”

“Then please allow us to pay for your lodging this night. The Holy Father, as you may have heard, is very generous. Surely he would endorse a small donation to worthy Christians.”

Brother Honorius looked stunned. “Did you state that you are bearing coin? This cannot be tolerated. You must immediately divest yourselves of all material wealth before continuing another step. To do otherwise would be sacrilegious. Furthermore, I assign no credence to your tale about being on a mission for His Holiness. You are clearly two nobles who are attempting to buy their way into God’s Kingdom. Look at your hands and feet. They have obviously never been employed in honest toil.” He paused and then glared at us with ferocious eyes. “I curse you and all of your descendants for mocking the travails of the Lord's faithful.”

A look of abject terror enveloped my friend’s face. He dropped to his knees and surreptitiously tugged on my tunic to indicate that I should join him. “Oh, please, good sir,” he pleaded in a desperate voice. “Remove your curse. We beg you. We will swear on any relic or on God’s Word that our journey was sanctioned by the Holy Father. We never meant to contravene any tradition of pilgrimage. Our sin is one of ignorance, a commodity that we possess in abundance. We will gladly distribute what little money we carry to the indigents of Andria on the morrow. Meanwhile, please accept our offer to pay for your lodging on this night. The Lord surely looks with favor on the devotion that you and your followers have displayed. Why not accept this gift of one restful night on a mattress as just reward for your diligence and charity in sharing your knowledge and experience with us? We would also be most grateful if you were to lead us in the prayers of Vespers and Compline this evening. We can then resume our journey better versed in the true spirit of pilgrimage.”

Brother Honorius responded that he had been forced to sell his relics earlier in the journey, and there seemed to be no copy of Holy Writ within reach. Instead, he forced Deacon Agatho to swear on my head that the Holy Father had assigned our mission. After the oath was sworn, Brother Honorius agreed to the offer. Agatho departed to make arrangements with the innkeeper. We then led the mule to the stables to relieve the beast of its burden. We ordinarily unloaded the mule together, but on this occasion Agatho assigned me the task of obtaining food and water for the animal. He dealt with our belongings. He took special care with two small caskets that I had not noticed when we had unpacked the mule on previous evenings. They must have been heavy, for he handled them one at a time, and after setting each down he grabbed his back in pain. Furthermore, I noticed that my sword seemed to be missing. I was about to mention it to him, but as I began to open my mouth, I noticed his furrowed eyebrows, which brought to mind his instructions to maintain silence in the presence of others.

The innkeeper set up straw mattresses on the floor for all seven of us. Before we retired for the night Brother Honorius led us in prayer. By the light of three candles, which he explained in hushed tones were symbolic of the Holy Trinity, we formed a line in which Brother Honorius was first and Deacon Agatho last. Honorius and his followers then maneuvered around so that the line became a circle. All five removed small scourges from their cinctures. Brother Honorius provided the deacon and me with one as well. We all stripped to the waist and began the prayers. At intervals designated by the monk we applied the lash to the man in front of us. Neither the deacon, who was behind me, nor I exerted much effort in the blows that we administered, but I could see that the back of the man before me was already striped. I could also sense that Honorius was applying the whip with determined vigor to my friend’s back, but the deacon never winced or complained.

At the end of the session Agatho thanked Brother Honorius for awakening spiritual feelings that had long been dormant in his soul. He confessed that his dreams had been troubled in recent days, and he looked forward to a just man’s sleep. In contrast, my sleep that night was rather fitful. Several times I was awakened by whimpering and moaning emanating from the direction of our newfound companions.

Shortly after first light we were roused by the innkeeper and the stableboy. They were visibly distraught. Only six mattresses were occupied; Brother Honorius was missing. We were all drowsy as we followed the innkeeper to the barn. There we beheld a very peculiar sight: an inert man suspended upside down on a rope affixed to a hook in the rafters. His unshod feet were bound together, and his tunic hung down over his face and arms. His breeches were missing. On his chest and back a strange symbol composed of three intersecting lines had been drawn in blood. A pool of the same substance was visible on the floor beneath him.

Suddenly the body began to thrash about, and indecipherable noises emanated from the area of the head. As the rest of us rushed to assist the poor fellow, Deacon Agatho dropped to one knee and crossed himself vigorously three times. He then cried out in a panicked voice, “By the travails of the Holy Family, Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, this is unquestionably the work of the avenging Archangel Samael. I recognize his sign. It was taught to me by Father Lawrence, who learned it from Pope Gerbert,[9] a brilliant man with legendary connections to the spiritual and supernatural realms.”

At these words the other pilgrims recoiled in revulsion. Agatho was busy reciting Pater Nosters and Ave Marias. The task of lowering the hapless monk to the floor was left to the innkeeper, myself, and the stableboy. We soon discovered that the monk’s bloody breeches had been thrust in his mouth and the leggings had been tied firmly behind his head. When we had fully released him, he tried to talk, but we could make no sense of his utterances. In frustration he opened his mouth wide and pointed inside. We were all aghast to see that his tongue had been severed. Furthermore, it soon became apparent that the reason that he had been unable to help himself was that both of his thumbs had been crushed into useless little paddles. His whole demeanor indicated that Brother Honorius was experiencing intense pain.

“Behold, it is just as I feared!” cried Deacon Agatho as he pointed at a thumb. “Gaze upon the handiwork of the Hammer of Samael! Of that there can be no doubt. I wonder what this wretch did to arouse the wrath of such a powerful celestial entity. We should all pray that the archangel’s thirst for vengeance has been sated or that he slakes it elsewhere.”

Honorius gesticulated wildly in the deacon’s direction, but none of us could understand his vocalizations. It seemed that he might have been ratifying Agatho’s interpretation. We tried to calm him, tend his wounds, and help him arrange himself. Then the innkeeper led him to a wagon to be transported into a nearby village in which resided a woman from Salerno who had effected many notable cures using the sacred Patella of St. Alban.

We resumed our journey the next morning. The deacon evidently had forgotten his promise to distribute our money to the poor folk of Andria. In fact, he seemed lost in thought and volunteered nothing concerning the strange affairs of the previous night. When we stopped to rest our naked feet, which were unaccustomed to direct contact with the road, I asked him whether Fr. Lawrence had taught him about Samael’s symbol before I joined the class.

“No, Longino,” he admitted. “I confess to inventing that symbol myself. When the conversation turned to the subject of coins I surmised from the glint in the monk’s eye that the blackguard planned to rob us. By craft, stealth, or force he probably has relieved more than one pitiable pilgrim from the funds or goods in his possession. This time, however, he made a poor choice of victim. I snuck into the barn just after he did, and I caught him examining the boxes that I had left in the stable. As he began to pry one open, I crept behind him and floored him using the pommel of your sword.”

“Are you saying that after you hit Brother Honorius on the head the Archangel Samael appeared and did all of that to that poor monk?”

My friend abruptly halted and stared at me for a few heartbeats with his head tilted to one side. “That is precisely correct,” he declared with firmness of purpose. “I incapacitated him, and then in the next instant the archangel materialized, maimed him, cut out his tongue, and strung him up. When his vengeance was complete, he vanished in a puff of violet smoke. Meanwhile I was dumbstruck by the awesome aspect of his celestial countenance.”

“How did you end up with my sword? Have you secretly been carrying it on your person?”

“No, no. It was on the mule, all right. I wanted to avoid publicizing the fact that you and I were bearing arms. So, I secreted it away as I was unpacking the mule.

“By the way, I must compliment you on the way you kept your tongue behind your teeth. You admirably followed my lead throughout. I doubt that anyone suspected that we were not what we claimed. You passed the first exam, but before this adventure is over,” he predicted, “your discretion may be tested again.”

When we resumed our walk the morning's events paraded through my mind. At last I paused to address my companion, “There was no archangel. You did all of that yourself!”

Deacon Agatho looked at me anew, tilted his head slightly again, and replied in a soft voice, “What brazen effrontery you show your elders! How dare a mere stripling posit such an accusation of one who has solemnly sworn an oath to serve the Lord?

“Oh, I just thought of something.” He inserted his hand into his scrip and retrieved two pairs of sandals. He placed his on his feet and threw the other pair to me. “It might be wise to wash yours first.”

[1] The ancient Roman holiday of Ferragosto is still celebrated in Italy for several weeks in the middle of August. The feast of the Assumption falls on the 15th.

[2] September 29.

[3] Guido of Arezzo, the inventor of musical notation, visited Rome in 1028 as a guest of Pope John XIX.

[4] As late as 1590, Pope Gregory XIV ruled that a fetus could be aborted as long as the “quickening” had not yet occurred.

[5] The current church of St. Mary in Palmis was constructed in 1637.

[6] In the text the deacon’s proper name was always written in Greek.

[7] The author used the term “malaria”. He almost certainly was referring to the air itself, not the familiar disease.

[8] In the text the Latin term used by Agatho referred to an immature rabbit.

[9] Pope Sylvester II (946-1003), who was considered by many contemporaries to possess magical powers.