During my long pontificate[1] I relied heavily on two men, my cousin Cardinal-Bishop Peter and Hegumen Bartholomew. Peter steadfastly supported our goals through both the good years and the difficult. He has now claimed his celestial reward.[2] The hegumen was an extremely conscientious and resourceful man who, more than any other in my acquaintance, dedicated every aspect of his life to the Church.

Either my cousin or the hegumen would have been an excellent choice as guarantor of the safekeeping of this document. Since both have now permanently departed this earth, I must entrust this work to someone else. I have chosen Bartholomew’s worthy successor in Grottaferrata as its warden. I hope that the current hegumen will undertake whatever measures are required to preserve it for posterity. Future pontiffs who read its contents will appreciate the wisdom of the policies implemented by Pope Benedict VII, Pope John XIX, and me. They resulted in decades of peace, prosperity, and propagation of God's Word in the first half of this troubled century. Any honest comparison of those decades with the preceding and subsequent ones leads to that conclusion.

Readers will likewise learn how enemies of my family sowed the seeds of perdition that produced chaos in the western Church and resulted in the inexcusable and disastrous rift between our fellow Christians in Constantinople and the Holy See.[3] This catastrophe could easily have been averted; the Greek and Roman rites had coexisted for centuries, and the differences in doctrine between the two patriarchates have never been daunting.[4] Tremendous damage has been inflicted by the rash usurpers whose arrogance was equaled by only their ignorance. Alas, now that the very fabric of Christianity has been rent in two, mending will require consummate skill and dedication. It may not be possible.

The key to maintaining a lasting relationship with eastern Christians has always been good communication, which was obviously lacking during the years in which the papacy languished under the auspices of the Crescentius family. My predecessors, Pope Benedict VIII and Pope John XIX, painstakingly reestablished productive relationships with officials of the eastern Church. I prioritized strengthening those ties throughout my pontificate. I composed detailed letters in Greek at least once a month, and I dispatched them to the Patriarch of Constantinople through the usual channels. I diligently made certain that the patriarch and the emperor were always apprised of our intentions and viewpoints in all important matters, and I often sought the patriarch's opinion. I deemed it crucial that he receive official statements from the Holy See because my pilgrimage showed me that the bustling trading center of Constantinople played host to a revolving cast of merchants and sailors who were notorious for spreading rumors and wild stories. No one could be certain which outlandish tales reached the patriarch’s ears and which took root in the imaginations of the Greek Christians.

The patriarch sent me epistles, but in the first year or so I found the contents disturbing. In the first place, the quantity of letters that I received from him was far smaller than what I had sent. Furthermore, the patriarch often failed to respond to issues that I addressed in detail. Occasionally he politely complained that the Holy See seemed to be neglecting the Greek Church. Such remarks troubled and confounded me.

Now and then I expressed to my advisers my concerns about our relationships with the eastern Church. Following one such meeting the hegumen asked me to hear his confession. Since he surely must have had a regular confessor, I was amazed that he would request this from me, but I agreed without hesitation and arranged for him to visit me after the evening meal. He revealed that his request for a private confession had been a ruse. Instead, he informed me that communications that he and other monks had received from their associates in Constantinople had indicated that my letters to the patriarch had not been received by His Beatitude. When the hegumen asked me if I had a copy of them, I assured him that I had. I have always been maintained copies of my correspondence to ensure its availability to my successors.[5]

Over the next few days I assembled a package that contained copies of the letters that I had written to the patriarch. I personally delivered them to the hegumen for transmission to Constantinople. Within a month I received a warm greeting from Patriarch Alexius.[6] His long epistle addressed nearly every item in every letter in the package. Thereafter, I entrusted the hegumen with all correspondence destined for Constantinople, and our relationships with the patriarch subsequently became extremely cordial and productive. I never discovered why the original letters never reached the patriarch.

I also exchanged letters with Prince Casimir. The ones that I wrote to him were full of encouragement and blessings. His were both inspirational and frustrating. The young man heroically faced innumerable challenges in his quest to reunite his nation, appease the peasants, solidify the Christian Church in Poland, deal with resistance from his subjects, and repulse incursions from external forces. He admitted on one occasion that he had reached the precipice of despair and pined for the blissful tranquility of the abbey's cloisters. I dedicated many prayers to his cause, and I asked Cardinal-Bishop Peter to direct as much of the Church’s resources as he could spare to assist his efforts. As great as my determination to help Casimir prevail was, it was exceeded by my fear that our monetary support might not suffice. A week of fasting and prayer led me to conclude that the physical presence in the area of the Vicar of Christ himself could provide an effective rallying point for the prince’s cause. However, when I announced my intention to journey to Poland to demonstrate to the Slavic Christians how important their struggle was to the Holy See, my father refused to consider the matter. “You are the Bishop of Rome,” he proclaimed. “Your first duty is to its citizens.”

“I am also the Supreme Pontiff of all Christendom,” I countered. “My primary duty should be to bring appreciation of the Lord’s Word to all mankind. We live is a critical period in Church history. I have prayed for several weeks about this situation, and I firmly believe that the Holy Spirit has shown me the way. I have determined that my presence could be a decisive factor in maintaining the impetus of Christianity in the Slavic regions and in keeping those lands under Roman hegemony. My mind is made up, and as pontiff the authority is mine.”

My father leaned on his elbows and locked onto my gaze. He spoke slowly and firmly. I can still recall his exact words. “No.” I felt my heart beat three times. “You are not going to Poland, and you are not going to the moon. Your business is in Rome. If you depart, your pontificate will be forfeit.”

His expression made me blanch. Even now I can visualize every detail of his face. His visage reflected immovable determination, and just below the surface was the unmistakable hint of imminent peril. I was incapable of action. I neither confronted him nor acted independently against his wishes. A more courageous or more devout man would have offered more resistance. At the time I interpreted my father’s words as a personal threat that was only thinly veiled. Perhaps I erred. He may have intended merely to warn me that my claim to the Throne of Peter was more fragile than I imagined. If that was his aim, he showed uncanny prescience.

I stayed in Rome. I continued to plan how I might personally aid the prince's cause in Poland, but I neither acted on those plans nor mentioned them in my father's presence.

I deemed maintenance of communication with the German emperor of equal importance to the relationship with Constantinople. I sent my letters to the care of Bishop Wipo, Emperor Conrad’s chaplain. We enjoyed a lengthy and amicable correspondence. Whenever I received a missive in return, I immediately shared the contents with my father, my brother, Cardinal-Bishop Peter, and other advisers. They evinced profound interest in all news of either the emperor or his many vassals and sub-vassals. My father occasionally explained the intricacies of these relationships, but I had difficulty grasping who was a vassal of whom. The complex array of dukes, counts, barons, and margraves refused to sort themselves out in my mind. Pronunciation of their names often seemed incompatible with the workings of my tongue, and the alignments seemed to vary with each discussion. The relationships were difficult for me to comprehend, much less remember. They reminded me of a spider’s web in which each node was joined in some mysterious way to every other node. I relied on the advice of my father and the others in dealing with the Germans.

Bishop Wipo’s letters emphasized the emperor’s growing concerns about the activities of Aribert, the Archbishop of Milan, a city that had long enjoyed a special standing. Aribert was a fervent supporter of Emperor Conrad II in the first few years[7] after he had been crowned. Later the archbishop asserted his right to make appointments in sees near Milan when bishops invested by the emperor needed replacement. The archbishop even deployed an army into the field in support of his claims. This action alienated many nobles, but in some areas it also brought to a boil much anti-imperial sentiment that had long been simmering.

Bishop Wipo sought an official ruling from the Holy See. He indicated that the emperor was contemplating a trip to Italy to assess the situation and terminate this irritation. This news drew my family’s rapt attention. The emperor controlled, at least nominally, territories on both sides of the Petrine Patrimony.[8] For many years the pontiffs had respected this arrangement, but a powerful German king leading forces to Italy made for an uneasy situation. The emperor had sworn to protect the papal holdings from threats originating both inside the peninsula and from beyond, but a reckless emperor could pose a genuine threat to the institution of the papacy itself.

My written response to Bishop Wipo was, at my father’s insistence, polite but noncommittal about the state of affairs in northern Italy. My ignorance of the details made it easy for me to assume that perspective. At the same time I enclosed a letter to Esau Lieberman in which I solicited his advice in responding to an imaginary outbreak of earaches in Rome. My friend returned a long response that contained a list of questions concerning the nature of the pain, its precise location in the ears of the victims, and the classes of people who were so inflicted. He also inquired if the effects were limited to clergymen, if the problems were primarily in the right ear or the left, and if the sufferers experienced concurrent symptoms.

I brought Lieberman’s document back to my apartment. I then withdrew from a cabinet two slender pieces of carved wood a few spans in length. By design one fit within the other, and the interior piece slid easily back and forth. When we were attending Fr. Lawrence's classes, Gerard gave me the device and taught me how to use the markings on each to find the secret meaning in encoded documents that he had composed. We used only the fourth, thirteenth, seventeenth, twenty-second, twenty-ninth, and thirty-fourth letters of each line, and each was translated to a different letter. The process was tedious, and I often made mistakes. The translated text indicated that the emperor was about to assemble in Augsburg a complement of officials knowledgeable about politics on the Italian peninsula. Even the Bishop of Parma and the Margrave of Tuscany planned to undertake the difficult journey. Lieberman did everything he could to be included in the gathering. He felt confident of an invitation.

I informed my brother and my father that my contact in Germany had disclosed that the emperor was holding meetings with his advisers and informants about the situation in northern Italy. My father demanded to know the source of my information. I confided that when Bishop Wipo had visited Rome I had secretly become friends with Esau Lieberman. My father initially dismissed information received from a Jew. However, when he learned of the meetings from his own sources, he pressed me to show him the the physician's letter and insisted that I explain how I communicated with him. I steadfastly refused to provide any details. I told my father that because I appreciated the sensitive nature of the relationship, I always destroyed communications from my Jewish contact after I had mentally digested the contents. I never made notes of my own. In the end my father reluctantly conceded to me the right to communicate with Esau Lieberman on my own terms. My senescent mind can recall no other circumstance in which Count Alberic allowed my wishes to prevail over his own.

Shortly thereafter chaos erupted in northern Italy. My brother and my father monitored the situation closely and informed us of developments. However, I never felt confident of my grasp of the details. My family was convinced that it was important to persuade the emperor to stay on the other side of the Alps. They must have had a good reason for their strong feeling about this, but my recollections of the previous royal visits did not include the sense of dread that permeated this set of meetings. In late November[9] I received another letter from Esau Lieberman that indicated, in code, that the emperor planned to arrive in Italy before the snows closed the passes. Lieberman later wrote that the emperor and his party spent Christmas in Verona.

The cryptic message in that letter also emphasized that people in Verona had whispered outrageous lies about Roman affairs to the emperor. Over the years my family had often dealt with calumnies spread around Rome by the Crescentius family. We had, in fact, been repeatedly required to counter them in all three recent pontificates. I naturally assumed that our ancestral enemies, the worthless riffraff from the Sabina region, had gained the emperor’s ear. However, I learned that the most outlandish charges were, in fact, leveled not by the Crescentii, but by Italian clergy, primarily monks. The Toad himself had journeyed to Verona while the emperor was lodged there. Although the despicable runt never spoke with the emperor directly, Lieberman suspected that some who personally counseled Conrad had delivered reports fabricated by the Toad. The emperor’s response to these villains was evidently noncommittal. Thanking them for expressing their concern, he withheld pledges of action or intent.

I informed my father and my brother of the emperor’s arrival in Verona. A day or two later they confirmed it through their sources. My father stressed that we must take advantage of Conrad’s presence in Italy to cement the relationship between the most powerful man in Europe and the Holy See. My brother opined that we should simultaneously make a concerted effort to strengthen our ties to families that had supported our cause and those that might be convinced to aid us in the future. He proposed that we strive to establish an alliance with Count Gerard of Saxo,[10] whom my brother cited as an upstanding man of untarnished reputation. Because of his standing and his relationships with other land owners, he was the sort of man who could also help us rally other influential people to our cause. Gregory therefore suggested that a cadre of us should journey to Gerard’s castle. My presence was required. Gregory’s informants reported that the count was very respectful of the papacy, and he would probably be thrilled to host a pontifical visit.

I looked forward to this excursion, if only to leave my Roman prison. The journey to Poland that I had proposed would have been preferable, but this trip would at least provide an opportunity to view new scenery and meet new people.

During the previous year or two I had spent as much time at the stables as my duties allowed. I greatly admired one of its horses, a large chestnut stallion. When I made known my interest in the horse, he was given to me, but first the stablemaster had him gelded in order to constrain his natural fieriness. I would have opposed this, but my opinion was not solicited.

I named him Beltempo after the steed that my distant relative had named as Senator of Rome. On our gallops in the countryside I often envisioned the pair of us embroiled in thrilling adventures similar to those described by Pope John XII. Upon returning to my apartment I would retrieve my transcriptions of the diaries and reread the portions that most excited my imagination. I found both experiences—the rides and the reads—to be enjoyable, relaxing, and provocative.

Just before sunset our party approached the castle in Saxo. We had pressed the horses for the last hour, and they were spent. We were greeted at the gate by a small young female mounted on a large horse. From the saddle she barked commands at three groomsmen who accompanied her. I was honestly shocked by both her rugged demeanor and the scandalous language that she used with the servants, who were all on foot. Whenever one of them moved too slowly, she steered her steed in the the miscreant's direction, drew a small whip from the rope that girded her waist, and rained blows on him. In contrast, her horse must have consistently met her standards; she never whipped the animal.

The girl's air was different when she greeted our party. She used the proper titles in addressing us while proffering on behalf of her father a genial welcome to Castle Saxo. Her given name was Divota, but she preferred to be called Tigra. In fact, Tigra definitely suited her, and I heard no one, not even her father, address her as Divota. She slid off her huge horse in one graceful motion and landed on her bare feet as she casually flipped the reins to a groomsman.

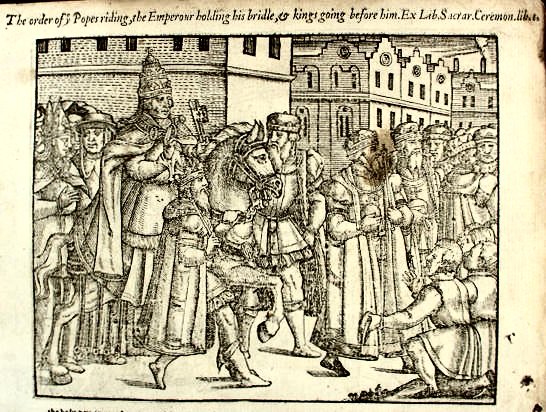

Tigra led us through the gate and introduced her father. The count was three times as massive as his daughter and perhaps one tenth-part as energetic. He insisted on performing the role of strator[11] for Beltempo. As soon as I dismounted, he knelt to kiss my foot. Because I was wearing my boots, I told him that that would be sacrilegious. I explained that the ritual of kissing the pontiff’s foot was instituted to pay homage not to the man who wears the papal slippers but to the cross sewn on the top of the slipper and to what that cross symbolized.

During this exchange Tigra rolled her eyes and covered her mouth to conceal her amusement. I correctly concluded that she had no intention of performing an act of obeisance toward me or anyone else. That suited me, too.

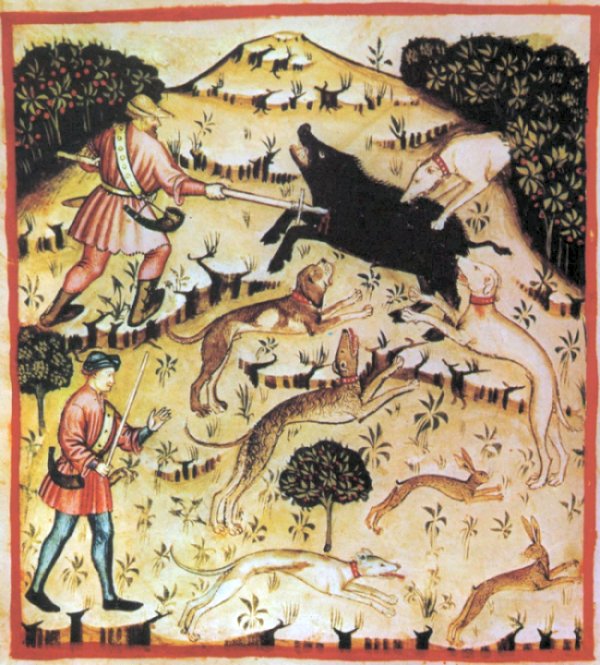

The count explained that we would feast that evening. A hunt was planned for the next day. The best time for hunting pigs was early in the morning, and he hoped to begin just after dawn. No one had informed me that I would be allowed to participate in a hunt on this trip. This was a new and exciting adventure. Several times a year my father and my brothers organized formal hunts, but I was never asked to join them. The count, however, had insisted on my inclusion. He may have wished to impress me with the quality and vastness of his hunting grounds. In any case the prospect of putting Beltempo through his paces in an actual hunt thrilled me. I had often practiced directing him this way and that through the brush in anticipation of such an opportunity. I had great confidence in my mount's grace and quickness in hot pursuit of wild game. I had often visualized a huge boar thrashing away the last few moments of his life on the end of my sturdy lance. I was not sure what blend of emotions would engulf my spirit when I felled the beast, but I was eager to discover the answer. It would be a grand time.

The remainder of the second day had also been planned in detail. Count Gerard scheduled the first business meeting for the afternoon following the hunt. My father admonished me that my participation would be limited to a prayer for guidance at the beginning and a blessing at the end. My brother Gregory sat next to me, and if I tried to say anything, he promised to cause me great pain. I took his threat seriously. Having no personal agenda, I was happy to assume a passive role.

“And above all, don’t forget about this.” He showed me his powerful right fist. “If you lose control, it will drive your chin up to your forehead. You know what I mean, do you not?”

I nodded.

The food and the wine at the first evening's feast were exceptional. Tigra personally oversaw the staff of both the kitchen and the wine cellar. Nothing escaped her notice as she scurried about issuing instructions and inspecting the fare. The obvious respect that the servants displayed for their mistress was tinged with fear. She never drew her whip, but she did lay a menacing finger on it a few times.

Only when everyone else had been served did Tigra sit and begin to eat. She quickly caught up with the rest of us. I marveled at Tigra’s ability to stuff so much food so rapidly into such a small body. She proved able to outeat and outdrink everyone in our party, a spectacular feat. My brother Gregory was renowned for his prowess at the table.

At supper the count informed us that Tigra’s mother had been the most wonderful woman who ever trod on dirt. He had met her in Agrigento[12] on one of his trading excursions. He was enamored of her from their very first meeting, and she was the focal point of his life until she died two years back. Count Gerard was devastated. He was only now beginning to emerge from his grief and resume an active role in managing the castle and the surrounding estate.

Tigra also missed her mother, but the count told us that their relationship had often been quite stormy. When still an adolescent Tigra began to assert her independence, and she resisted whenever her mother tried to make her act like a young lady of nobility. Tigra rebelled against all attempts to limit her activities or prescribe her attire and mannerisms, and, as I had witnessed, she employed colorful language that could easily turn vituperative. The count loved both women in his family so much that he had been either unable or unwilling to take the side of either his wife or his daughter. Now that his wife was gone, he was both devoted to and dependent on Tigra, who had assumed command of most aspects of life in the castle.

After the feast Tigra led our party on a short tour of the castle’s impressive interior, culminating in the presentation of our rooms to each of us. My chambers were last, and so Tigra and I were alone when she unlocked the door and presented me with the key. As I entered, I I felt a pinch on my rear, but when I turned around, Tigra was already down the corridor at least ten feet away, and no one else was in sight. Perhaps Satan had perpetrated the attack. If so, he achieved his purpose. Although I felt exhausted from the long ride and the marvelous feast, and the bed was quite comfortable, I was so excited about the adventure that I slept only fitfully.

When the hunting party assembled shortly after daybreak, we learned that the master of the hunt was neither the count nor his game warden, but Tigra. I had never heard of a female riding in a hunt, much less organizing it. She explained that all hunters would be mounted, provided with wooden lances, and stationed in a line in a nearby meadow to wait for pigs to emerge from the brush. Meanwhile the handlers would loose the hounds into the thickets to roust the beasts from their hiding places and drive them toward the line of hunters. Tigra, still barefoot, assumed the leftmost spot on the line. The count sat grimly on his steed at the other end. Beltempo and I took our position just to Tigra’s right. For about half an hour the tension mounted steadily as we held our nervous mounts in place. We could see no hounds, but we could definitely hear them baying. My right hand firmly gripped my lance; my left held the reins. Suddenly three pigs emerged from the thicket. As soon as they detected the hunters, they wheeled to the left and attempted to outflank the hunters on Count Gerard’s end of the line. My brother Gregory and the count gave chase. The rest of us held our positions and waited for more pigs.

We did not wait long. A large boar burst through the brush and sped toward us. When he saw the line of hunters, he turned sharply to the right. Tigra expertly restrained her mount so that Beltempo and I could run him down. This was the moment that I had been anticipating; I felt calm and ready. I urged Beltempo forward at full gallop, and within a few heartbeats we were almost upon the beast. I held my breath, lowered my lance, and leaned forward. The pig must have heard the hoofbeats; he suddenly veered to the left just as I lunged forward to drive home my lance. I adjusted my thrust, but the lance only grazed the hog and stuck in the dirt in front of Beltempo, who was at full gallop. As my beloved mount stumbled helplessly forward, the lance's shaft snapped, and I was flung skyward over Beltempo’s head. Even now I can clearly recall seeing the ground approach, but I have no memories whatever of the next three days.

My first sight when my mental faculties resumed functioning was of Tigra. As soon as she sensed a glimmer of consciousness on my face she spewed a stream of ruthless invective at me. The following words convey her meaning well enough, but they fail to capture her exceptionally derisive tone: “So you finally decided to wake up? I hope that you enjoyed a nice rest. What kind of idiot are you? Do you realize that your reckless acts forced me to slay that wonderful horse? Let me tell you something. I did not enjoyable having to stab that perfectly innocent and sublimely beautiful animal over and over until his life was extinguished.

“Do you even know what is required to put a horse with broken legs out of its misery? Have you ever tried to do it? It is not easily accomplished. As soon as I reached him I jumped up and slit his throat with my dagger causing blood to spout all over me. It was hot, bright red, and sticky, and it was everywhere. The stench sickened me so much that I nearly lost my footing. Still the miserable animal thrashed around in agony trying to rise to his feet. I seized my dagger with both hands and plunged it with all of my might between his ribs in hopes of hitting his heart. Even after that blow he still attempted, vainly this time, to rise again. I felt helpless. My dagger was stuck in his chest all the way to the hilt, but in his agony he had flung my blood-soaked body several yards away. I lay there trying to catch my breath as I watched his desperate struggle. He finally collapsed and expired with one eye fixed on the woman who had slain him.”

At this point her anger yielded to extreme sadness. “This was absolutely the worst experience of my life. I cried and sobbed all day and half the night. I never cry. I never sob, not even when my mother died.”

The bitterness returned. “This was entirely your fault, and I hate you as I have never hated anyone.”

I was dumbstruck. I had no idea where I was; I only vaguely remembered who I was. I lay nearly motionless as this diminutive woman furiously beat on my chest with both hands. It was as if she had appeared in my sleep when I was paralyzed. I finally managed to mumble, “What did I do? Did I hurt someone’s horse?”

I can still hear her scream of rage and frustration as she whirled and padded out of my chamber. Left to itself, my mind began to assemble shards of memory. I joyfully recalled our arrival at the castle and how much I looked forward to the hunt. I remembered us taking our positions in the line, and suddenly those last few moments of tragedy burst into my thoughts. Oh, no, it was Beltempo! My clumsiness and incompetence had forced my beloved steed to endure unfathomable pain and a gruesome death, and the little lady who had just given me a tongue-lashing was forced to play a horrible part in it. There I lay in a strange bed as helpless as a baby. As usual, someone else dealt with the problem that I created. I hated myself at least as much as Tigra did. Other adults pay for their mistakes. I was the exceptional one. I had made countless blunders in my lifetime, but someone else always stepped in to mitigate the catastrophic results. This was so wrong. Excruciating guilt led to deep depression.

For a day and a half the papal party had exchanged information, strategized, and negotiated with the count. Most of them returned to Rome after the successful conclusion. My brother Octavian remained at the castle to escort me home. I spent six more days at Saxo before I was judged fit to travel.

During my convalescence several servants cared for me under Tigra's supervision. Her attitude toward me evolved over the course of the next few days from explosive anger and hatred to simple pity. I preferred the anger and hatred. I was not worthy of pity. Although I cared only a little if other people liked me, I resolved to earn at least a bit of respect from this young lady for whom my actions had brought so much grief. One day when she brought me breakfast I praised the quality of the care that she had provided and thanked her for the time and effort that she had devoted to my recovery.

She responded only indirectly, “Are you really the Supreme Pontiff? Aren’t you rather young and reckless to hold such an important office?”

“Well, yes. One or two popes were younger when they assumed the Throne of Peter than I was, but not many. At least one was even more reckless, as well.”

“And you are a priest, too? You do not act like a priest.”

“Of course I am a priest. The pontiff is the Bishop of Rome, and every bishop must be a priest.[13] Although, in fact, several cardinals are not priests.”

“Did you always want to be a priest, or did your family assign that role[14] to you?”

I suppressed a smirk. “I never even considered becoming a priest. I always wanted to be an adventurer. Even as a child I hoped to emulate Odysseus, sailing the seas to explore new and strange lands. I longed to discover what was on the other side of the sea or the hill. I dreamt of slaying monsters or solving puzzles that prevented the completion of my quest. Instead I am trapped in Rome. Mostly I officiate at religious ceremonies or attend boring meetings in which my opinion is never welcome. This trip was the first time that my father and others who administer the Holy See allowed me outside of the city. After this fiasco, it will certainly be the last, at least for the nonce.”

“Who is Odysseus? Was he a member of your party? I recall no one with that name.”

My answer to that question became the cornerstone for the construction of a new and marvelous relationship between Tigra and me. We spent unimaginably pleasurable hours together. I related the poet’s epic tale with as much vigor and enthusiasm as I could muster. The story, I stressed, was much more powerful in the original Greek. I recited a few lines that I had memorized to give her a feeling for the rhythms and sounds that Homer had employed to bring the tale to life. My narrations enthralled her, and she repeatedly interrupted me with questions. Her reaction called to mind the wonderful feelings that I had when I first encountered the story. She expressed some of the same concerns about the relationships among the gods and the heroes that arose in my sessions with Clement. She also marveled at the fact that the city of Tusculum had been founded by Odysseus’s son. I merely shrugged when she asked if I might be descended from the hero.

I never touched my breakfast the day that she asked me about Odysseus, but I was more than sated by Tigra’s appreciation of the Odyssey. She spent nearly all of my convalescent period at my bedside absorbing the details of the epic naval adventure.

On the day of my departure for Rome, I told Tigra that, although I had described most of the waterborne adventures of Odysseus and his crew, the equally compelling ending of the story remained to tell. Also, Homer had written another epic poem about another hero’s engagement in a war that lasted for a decade. Tigra was surprised that in the Iliad Odysseus was considered neither a hero of the first rank nor a leaders of the Achaean troops. I also mentioned that there was a related tale—in Latin—about the adventures of another stalwart survivor of the same war who eventually founded the city of Rome itself. I promised her that I would write her regularly to fill in the details about both of these works. I could tell by the sparkle in her eyes that she could not wait to learn of these adventures, but the look quickly faded, and she lowered her head in evident shame.

Tigra assured me that she was certainly would enjoy reading my letters, but composing responses would cause her intolerable embarrassment. She confessed that she was just an unschooled provincial lass. Her mother had insisted that she learn to read and write, but she had devoted only enough effort to avoid chastisement. After her mother’s death she had abandoned both activities. The idea of writing a letter that would be read by someone of my upbringing and apparent erudition provoked anxiety. She had never written a letter to anyone.

For once in my life I found the appropriate words. “Listen to your heart, Tigra. If you feel like writing something, that will be wonderful. If you do not, perhaps we will see one another at some future time, and you can express your thoughts and feelings in person. If you decide that you would like to send me something, I will treasure it all the more because I will appreciate how difficult it was for you to create. In any case I will write to you, and I will always bring to mind the image of those bright eyes and that glowing face that I beheld as I related here in Saxo the adventures of Odysseus and his comrades.”

I will forget my name before I forget the beatific look on her face when I completed this little speech.

I always respected animals, but Tigra taught me empathy for them. I avoided the stables for more than a week after my return to Rome, but I needed a suitable mount. The head groom tried to persuade me to adopt a grey mare. She had a very nice disposition, but my attention was drawn to a spirited black stallion. When I asked to ride him, the groom made excuses. I persisted. Eventually he allowed me to mount him for a short ride. I remembered that Beltempo seemed to divine my intentions from the first time that I had sat on his back. I seldom needed to goad, direct, or rein him in. This beast was Beltempo's opposite in every sense. He fought me at every turn. He clearly wanted to impose his will on mine, and he relished my discomfiture. On Beltempo’s back I enjoyed the pure pleasure of feeling that horse and rider were acting as a single entity, but riding this steed was thrilling. I loved them both.

I forcefully ordered that the black stallion never be gelded, and I made everyone understand how serious I was. I pleaded with the groom to let me keep him. At first he invented excuse after excuse for denying my request. He considered his primary duty was to protect the pontiff, not to cater to his whims. After I had ridden the stallion for nine days in a row with no serious incidents, the groom relented, and the equine dynamo was mine. Until then I had not dared to call him by name even though I had been certain from the beginning that no name but Maltempo suited him.

I drafted a short letter to Tigra at least once per week. After I had recapitulated all the adventures described in the Odyssey, I took up the Iliad. I contrasted the attitudes towards war of Achilles and Hector. I described the heroic feats of Diomedes and the two Ajaxes in meticulous detail. I noted the secondary characters, including that rascal Paris, the wondrous Helen, and the Greek leaders, Agamemnon and Menelaus. I saved for last Virgil’s melancholy story of the fall of Troy, the ill-starred love between Dido and Aeneas, and the founding of Rome.

My letters also kept her abreast of my progress in transforming my stallion into a reliable mount. I longed to tell her about my distant past and those marvelous adventures alongside my marvelous companion, Gerard. I was sure that she would have been impressed and interested in learning about the lands that we visited, but I had sworn never to reveal the details. Besides, how could I describe my pilgrimage without mentioning the shameful circumstances that prompted it?

Once in a while Tigra sent me a letter in reply. Her missives were short, but I cherished every poignant word and phrase that they contained. I still know many by heart, but the details are not relevant to this work.

The miraculous reversal in Tigra’s attitude toward me convinced me that the hours that I had spent poring over texts with Brother Clement and Brother Alexius were of much greater value than I had supposed. I therefore proposed that our family donate more land to the monastery at Grottaferrata in recognition of the inestimable service of the hegumen and his followers for both the counts of Tusculum and the citizens of Rome. They were monks, to be sure, but the ones at Grottaferrata were our monks. My father showed no enthusiasm for this idea, but he eventually agreed..

How clearly I can still recall that first trip to Saxo! The images remain as vivid in my mind as any memory that I have. I still recoil at the shrill and exasperated tone in Tigra’s voice when she berated my disgraceful performance in the hunt. I also luxuriate in the sweet recollection of her expression as she posed questions about Odysseus and his companions. For me the experience in Saxo represented the depths of anguish and humiliation as well as the delightful thrill of establishing the basis for a long-term friendship. It was the adventure that I had desperately craved.

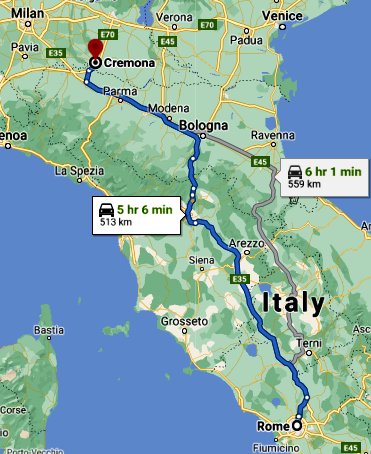

My confident assertion that I would never be allowed to leave Rome proved erroneous. Only four months later my father made a startling announcement. We all had been well aware that Emperor Conrad and a small army had crossed the Alps and descended into the Italian peninsula to deal with Archbishop Aribert[15] and the armed conflicts that had arisen in the vicinity of Milan. My father had decided that he and Gregory should attempt to arrange to meet with the emperor. Because of my position and my personal relationships with Bishop Wipo and Esau Lieberman, father concluded that my presence would be valuable. He arranged by messenger for the consultation to take place outside of Cremona.[16]

A day before our arrival there, we learned that the emperor had brazenly taken the archbishop prisoner. We met with Conrad’s representatives, who pressed me to excommunicate[17] Aribert immediately because he had broken many agreements. Moreover, the archbishop had allegedly hired a cutthroat to assassinate the emperor. Aribert, for his part, cited sections of treaties to substantiate his own claims to territory and rights of investiture, and he was insulted by the claim that he was involved in an attempt on an emperor or the condoning of such a heinous crime. Instead, he insisted that the emperor had flagrantly abused his authority and that despite his lofty rank he had no right to apprehend and hold captive a metropolitan[18] like himself. He also made the point that no imperial accusation involved matters of faith or morals[19]—except for the unproven and, according to Aribert, preposterous claim about the assassination. So, excommunication, by his reasoning, for such a political matter should not be considered. Rather, he argued that the Holy See could easily validate his legal claims and should therefore order the emperor to pay an enormous sum in restitution.

I informed the emperor and the archbishop that I appreciated the seriousness of all the charges. I also understood my responsibilities to both parties. I affirmed my respect for both of them. However, I admitted that I was too inexperienced to make a quick judgment about the validity of the claims. I needed more time to research the matter. I also indicated that I could not excommunicate the archbishop because I was not impressed with the evidence that Aribert had arranged the attempt on the emperor's life. Furthermore, the other charges did not appear to involve either faith or morals, the two areas reserved to the Holy See.

This response pleased my father. He never questioned it in public, and he did not scold me in private as he did when he judged that something that I did might be damage us politically.

The emperor’s icy expression indicated that he was not accustomed to analysis of his demands. Bishop Wipo, with support from Rudolph, essayed to help him understand my position. They emphasized that a pope’s primary obligation was to his flock, that is, the entire Church. Therefore, all pontifical judgments must necessarily be based on what provides the surest path to salvation for all concerned. Depriving any Christian, even a scoundrel like Aribert, of the sacraments instituted by our Savior would be a drastic step. The fact that Aribert had served as archbishop with skill and loyalty for a long time made excommunication seem very severe. Bishop Wipo announced that he was thoroughly impressed by my willingness to take time from my onerous schedule to weigh all of the evidence before I undertook such a measure.

I suspect that he knew how far from onerous my schedule actually was. The bishop’s explanation seemed to placate the emperor a bit, even though I thought that I had made it quite clear that there did not seem to be much evidence to weigh.

As Esau Lieberman had hoped, he was assigned to the emperor’s entourage. However, during our short stay in Cremona he found that treatment of medical emergencies took up most of his time, while my presence was required at the discussions with Archbishop Aribert and Emperor Conrad. There was no convenient time to meet with my friend face to face.

I returned to Rome convinced that our mission had been successful, but Gregory and my father fretted because the emperor and his wife decided to remain in Italy all winter. They were joined by their son Henry, who brought an army—as well as his wife—with him. The imperial contingent celebrated Christmas in Parma.[20] In the spring my father heard the dreaded news that the imperial forces were headed south. We never intended to oppose Conrad's progress even if he entered papal lands without permission. However, we wanted to maintain the integrity of our holdings if possible. My father decided that the best idea was to give the emperor what he wanted, Archbishop Aribert's excommunication.

I deplored the use of such a controversial pronouncement merely to placate one man, but my advisers unanimously insisted that there was no choice. The prospect of an irate barbarian emperor and his army on the loose within the Papal State was too horrible to countenance. I issued the public announcement on Easter Sunday.

The emperor led his troops through the lands of the patrimony, but they never threatened the city of Rome. The only members of their party who entered the city were the Empress Gisela and her attendants. My father insisted that I personally escort her to view the relics and graves of the apostles and to visit famous churches. I also presented her with a few relics that I personally had blessed. She seemed quite impressed by the experience. I, on the other hand, could not help but recall what Pope John XII had written of his escapades with Empress Adelaide. I swear that my behavior was beyond reproach.

Emperor Conrad and his army remained in southern Italy throughout much of the year. The emperor directed his energies toward resolving the complex discords among local leaders and to reestablishing imperial control over the abbey at Montecassino. He addressed the latter issue by installing a German monk[21] as abbot. During the summer he turned back north to finish dealing with Aribert, but large numbers of his party were soon stricken with a contagious disease. Esau Lieberman did a masterly job of protecting the German nobility from this infection, but when Lieberman himself contracted a virulent case, the desperate emperor ordered his remaining force to retreat to healthier climes north of the Alps.

I was very concerned about the condition of the emperor's party. My father assured me that this was a regular occurrence. The Germans had been driven back more often by Italian diseases than by military forces. Count Alberic was very pleased with the outcome. In retrospect the emperor's sojourn in Italy was probably the high point of my pontificate. I finally was gaining confidence in my abilities.

[1] Benedict IX’s first term as pope was the longest since that of Gregory IV, two centuries earlier.

[2] Cardinal-Bishop Peter died in 1049. St. Bartholomew the Younger died in 1055.

[3] The Great Schism occurred in 1054. The author discusses its proximate cause in more detail in Chapter 12.

[4] Aside from the fundamental dispute concerning the precise role of the Bishop of Rome, the most prominent theological issue was the insertion by the western Church of the word “Filioque” into the Latin version of the Nicene Creed. From time to time the Greeks also protested that the common use of images and statuary in western churches was idolatrous.

[5] In point of fact, only two letters written by Pope Benedict IX are acknowledged by the Vatican Library. Both are in Latin, and neither is addressed to the patriarch. No letters received by the pontiff are in the public record.

[6] This must be Alexius I Studites, who served as patriarch from 1025 through 1043.

[7] Conrad had been crowned in 1024, roughly a dozen years earlier.

[8] This peculiar situation dates back to the Lombards, who in the sixth century and following controlled northern Italy and large swaths of the south. The Carolingian empire won these territories by virtue of the conquests of Pepin and Charlemagne in the eighth and ninth centuries.

[9] This was probably 1036.

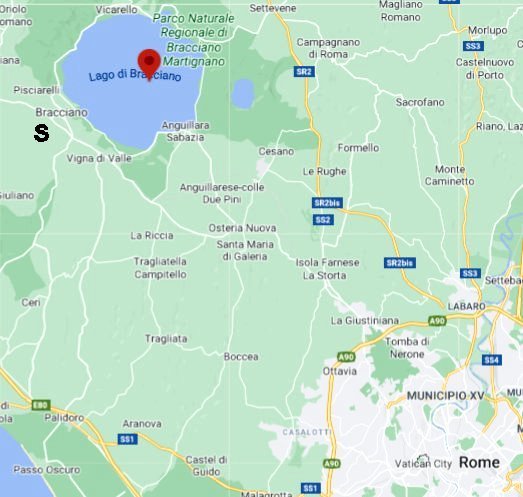

[10] In contemporary texts the count is also commonly called Gerard of Galeria. Neither Saxo nor Galeria is on the map today. The area controlled by the count was northwest of Rome and to the west-southwest of Lake Bracciano.

[11] A strator is one who leads another person's horse. Kings and emperors often played this role to show respect for the pontiff. Occasionally desperate popes had acted as strators for rulers whose support they sought.

[12] Agrigento is an ancient city on the southwest coast of Sicily.

[13] Almost everyone would say that this statement is incontrovertibly true, and yet Pope Adrian V (1276) was never ordained a priest.

[14] In many noble families the oldest son was the heir, and the second son joined the priesthood, willy-nilly.

[15] Aribert was Archbishop of Milan from 1018 to 1045.

[16] Cremona is about fifty miles southeast of Milan.

[17] All bishops had, or at least claimed to have, the authority to excommunicate any Christian. Those who suffered this fate were prohibited from receiving the sacraments. They were also often ostracized from the community’s social and economic activities.

[18] All metropolitans are archbishops, but many archbishops are not metropolitans.

[19] This is the only time in the entire document that the author discusses a question that could be considered theological or even philosophical. He never accuses anyone of heresy, and he never was called a heretic by any of his enemies.

[20] Parma is thirty or so miles southeast of Cremona.

[21] This probably refers to Abbot Richer I.