Every old man’s memory is unreliable. I can clearly recall many events within a few years of the emperor’s return to Europe, but I feel uncertain of the sequence and details. I am frustrated that no one can assist me.

All Rome was shocked to learn that the emperor and his daughter-in-law had perished shortly after returning to Germany. This pair of tragedies must have been a tremendous blow to Conrad's young son, Henry.[1] The period between the father’s death and the grieving son’s accession was remarkably short. We sent a letter to Bishop Wipo with our condolences to Empress Gisela and the young king and promised to pray for the repose of the souls of Conrad and Gunhilda. We also offered King Henry access to any assistance and advice that the Holy See could provide.

The response from Bishop Wipo was cordial but noncommittal. The courier’s package included a much longer letter from Esau Lieberman, who had been incapacitated throughout the return to Germany and for two full weeks thereafter. Lieberman’s letter posed a large number of questions about the malady that had stricken so many people in the imperial contingent during the ill-fated excursion in southern Italy. My friend requested details of the extent of the illness in each region, the approaches that local physicians employed to combat the outbreak, and a complete list of symptoms. He provided long sets of questions for both the people who attempted to deal with the outbreak and the surviving victims. I made a copy for the people who might know the answers to his questions after I had revised it a little to disguised the encrypted material.

An entire afternoon of painstaking work revealed the hidden message, which was most unnerving. King Henry was extremely upset that both his wife and his father had succumbed following the Italian adventure. His grief quickly had turned to anger. No institution or person was blamed for the deaths, but his mood was generally dominated by extreme and unpredictable wrath. He felt betrayed, if not by a specific person then by fate or by God. Unfortunately, Lieberman enjoyed no direct access to the new emperor, and neither did Bishop Wipo. Indeed, my friend intimated that this could be the last communication between us, or at least his last missive as a member of the emperor’s court.

Even more disheartening was Lieberman’s recounting of Henry’s activities during his sojourn in Italy. The prince had been much more receptive than his father to gossip and innuendo spread by the Toad and his cronies. King Henry specifically sought out Peter Damian,[2] a self-righteous gossip-mongering monk, and granted him an official consultation that lasted an entire afternoon. Lieberman had endeavored to learn what was discussed, but he was unsuccessful. The letter indicated that the emperor had subsequently established lines of written communication with both the abbey in Cluny and with Peter Damian in Fonte Avellana. Someone, perhaps Peter Damian, had spread slanderous tales about my pontificate. When the German contingent was still in Italy, Esau Lieberman had overheard that Henry had sometimes dared to refer to me as Pope Maledict.[3]

Bishop Wipo's next letter was polite but curt. He indicated that future communication intended for the emperor should be addressed to the care of his chaplain, Theodoric. The messenger’s packet contained nothing from Esau Lieberman and no explanation for the absence.

A month or two after the last letter from Bishop Wipo, my father’s sources reported that the bishop and his friend Rudolph had retired to Burgundy, where Wipo devoted himself to his writings and his music. Lieberman had reportedly fled under the cover of darkness just before the king issued a warrant charging him with theft of a substantial fortune in gold, gems, and relics. If the pseudo-Jew had subsequently been apprehended, his captors must have disposed of him with extreme haste and discretion. Although I feared the worst, I also retained great confidence in my friend’s resourcefulness.

Throughout my pontificate my father often directed his attention to the island of Sicily, which had been controlled by Saracens throughout his lifetime and long before.[4] A Byzantine general named George Maniakes, who was also the Catepan of Italy,[5] had undertaken a successful invasion of Sicily. He was aided in this endeavor by Normans and even some Norsemen.[6] My father, whom I never knew to fear any man, was extremely wary of this group. George Maniakes was by all accounts a giant, and the Normans were led by a man named Iron Arm.[7] We considered mustering a force to aid these valiant Christians in their sacred quest to retake the island from the Muslims, but Gregory considered the project unfeasible. Deploying troops to Sicily would obviously limit our ability to defend the patrimony. We needed to remain vigilant at least until Henry had clarified his intentions. Furthermore, the fleet that Pope Benedict VIII had amassed for his military conquests of the Muslims on the peninsula was no longer seaworthy, and other means of transportation were judged inadequate.

The Holy See's failure to assist to the Christian cause in Sicily was probably a blessing. The success of the Greek expedition was short-lived. George Maniakes, who was renowned for treating his friends and enemies with equal disdain, was abandoned by his erstwhile allies. He was recalled by the emperor,[8] and his departure allowed the Saracens to reclaim the entire island. Thereafter chaos seemed to reign throughout the Catepanate. I was astounded to learn that the Normans had seized the crucial port of Bari and other important locations long held by the Romei. The two Christian[9] armies fought several bloody battles in southern Italy. In the end the Greeks recovered Bari, but the Normans established themselves in several nearby areas.

The Abbot of Cluny, Odilo, deplored the seemingly ceaseless petty conflicts among Christians as much as I did. Monks from Cluny and its many affiliated monasteries garnered widespread support in Italy for the concept of Treuga Dei, which severely limited the days on which Christians could engage in armed combat. Whether lives were in fact saved due to those efforts seems unlikely. Would a commander suspend a siege of an enemy’s stronghold on a local feast day, as Treuga Dei required, and thereby allow the besieged free passage until sundown? Furthermore, delaying inevitable combat might only prolong the agony for non-combatants who resided nearby. Even if individual battles were shortened, the prescribed pauses might lengthen the conflicts unless the underlying disagreements were addressed during the peaceful periods. Nevertheless, Odilo deployed many eloquent representatives throughout Italy, and few dared confront them.

At some point in this period news reached us of a rebellion in Hungary, a land that had been shepherded into Christianity by King Stephen during the reign of Pope Sylvester II.[10] We learned that a pagan group that also included some Christians had taken up arms against the Christian rulers. The rebels had ousted the legitimate King Peter and placed on the throne a usurper named Samuel.[11] In exile King Peter sought the protection of King Henry.[12] I felt obliged to make it clear to Christians who had supported the rebellion that such behavior was unacceptable to the Christian Church, and so I excommunicated all the rebels. Isolated in Rome, I could do no more, and I never learned whether my action had the desired effect.

I respected King Henry’s decisive action to right a situation in which the character and motives of participants were clear. I longed to make my own mark by undertaking a journey to regions in which Christianity was engaged in day-to-day struggles with pagans or other infidels. I was certain that the pope must be in the front lines of the wars for Christian souls and, if necessary, to battle the forces of evil, but I never convinced my father that I should leave Rome. He was absolutely unyielding.

My correspondence with Casimir about his struggles in Poland continued. I arranged for the establishment of a monastery in Poland devoted to St. Adalbert in hope that it would help his cause. When I learned that King Stephen of Hungary had imprisoned Casimir, I dispatched a letter of protest to Stephen.[13] Casimir was quickly released. After departing Hungary, Casimir took refuge in Germany, where—at my urging—King Henry assisted the young man.[14] Casimir faced many daunting difficulties over the years, but in the end he reclaimed nearly all of Poland, and paganism was eventually rebuffed.

Among the cardinal sins pride ranks first. Even so, one of my most pleasant memories is of that period. I felt a great sense of accomplishment knowing that assistance from Rome and our prayers contributed to Casimir's success. Of course, I would have preferred to contribute directly.

In 1044 my father suddenly suffered a debilitating stroke and died within two days. I conducted the funeral Mass, and Gregory assumed all of the count’s remaining duties as well as his title. A period of mourning followed. I waited for two months after the entombment to announce my intention to visit Poland. By then Casimir was widely recognized as duke and had come to terms with Bretislav, the Duke of Bohemia. I asked Cardinal-Bishop Peter to oversee the arrangements for my journey. My brother and a few others attempted to dissuade me, but I was well prepared with a trove of persuasive arguments that I had amassed over the years, and I easily rebutted every objection. My duties in Rome had become even less demanding since I had announced the new cardinals.[15] Surely Cardinal-Bishop Peter, my brother Gregory, and the other officials could manage the city and the Apostolic See for a few months. I frankly doubted that they would even miss me.

Twenty-four stalwart men joined me as I began my second great adventure. Our company was small but dedicated to a sacred cause. As I write these words so many years later I still feel a small tingle of excitement. What a thrilling time! On this occasion, unlike on the pilgrimage to Jerusalem, I was in charge. No one would steer me away from trouble on this trip or tell me how to act or when to speak.

Progress for such a party was necessarily rather slow. Crossing Italy’s interior mountains with a large and inexperienced group was inevitably time-consuming. Our pace improved as we followed the Po River east to Chioggia. Our next goal was the most charming of cities, Venice. My second visit impressed me even more than the first. The lagoon was a beehive, with most activity involving the construction of sailing vessels. On all sides one could see ships in every phase of construction. A new one seemed to be put in the water every day.

Venice’s dominance of the seas[16] had clearly generated vast wealth for its inhabitants. On my first stay in the city with the baron and his wife I saw that Venice’s wealthy inhabitants lived much more comfortably than Roman nobility. On this occasion nearly everyone of any station in Venice seemed to enjoy an easier life than people in Rome or even in Constantinople or the other great capitals that I had visited.

We had, of course, informed the doge[17] of our plans, and he was an enthusiastic and jovial host to my contingent. He provided a delicious welcoming feast and very comfortable lodgings. We only planned to stay in Venice for two nights, but extending our visit for a day or two was very tempting. After all, no one in Poland expected us on any specific date.

On the second morning the doge himself awakened me for Matins. He was not alone. “Your Holiness, I was told that you already know this gentleman,” he announced with a grin. I was astonished to see Baron Dubay, who said not a word before prostrating himself before me to kiss my slipper. As he closed the door behind him, the doge smiled broadly again and added “I will leave you two to resume your acquaintance.”

A thousand questions fought for my tongue's attention, and yet I was speechless. The baron, on the other hand, wasted no time. “My business is urgent. Your Holiness, your presence is desperately needed back in Rome. Your enemies have spread vile rumors about you, and many Romans give them credence. The tipping point apparently was your decision to abandon the city in favor of what is called your fool’s errand in distant Poland. These are not my words, but they prevail in the streets of Rome these days.”

As he spoke I noticed that the baron's face was drawn, and he spoke in a breathless tone that I interpreted as exhaustion. It had not previously occurred to me that he had been riding all night, but that must have been the case. I found one word in his report most striking. “My enemies? Who are they? I was unaware that I had enemies in Rome of any great significance.”

“No one told me the details, but it probably began with the Crescentius family, as usual. In this case they apparently enlisted some clergy. On numerous street corners priests—or at least men who look like priests—have been declaiming that you have abandoned the Holy See. Monks have descended into the public squares to inveigh against your worthiness as a spiritual leader. Surprisingly detailed accounts of immoral and disgusting acts have repeatedly been attributed to you and your associates. Some claims are quite fantastic. For example, some have asserted that your horse is possessed by demons or by Satan himself and that you have spent so much time on his back that you too have succumbed to the forces of evil. The worst part is, according to what the hegumen related to me, that a few accusations have a much sounder basis in fact.”

I was thoroughly shocked at this news. Again my reply addressed only one word of his disquisition. “The hegumen! What does he have to do with any of this?”

The baron grunted. “Your naïveté dismays me. The hegumen and I have been in nearly continual contact since the new King of Germany made clear that Esau Lieberman’s presence in the imperial court was no longer welcome. Bartholomew long ago became convinced that you represent the Church’s best hope of remaining strong and unified. He and your family assigned you that role as a child. They provided the very best training and education that any pontiff, at least any pontiff raised on this backwards peninsula, could have. The hegumen is a simple man but extremely persuasive. He convinced many of us that this course was not only advisable but essential for the the Church's survival and growth. It shocks me that you seem unaware that the hegumen has been your staunchest and most influential supporter. Did you not realize this?”

He continued without waiting for me to invent an answer. “No time remains now for chitchat. We must hasten to Saxo. The others may return at their own pace, but we two must arrive at the count’s castle posthaste. Gather what you need and saddle up your diabolical steed.”

I still did not understand. “Why Saxo?” I asked. “If Rome needs me, should I not go to the Lateran to reassure the Romans that the rumors are untrue?”

“If only that were possible. Rome is no longer safe. Count Gregory[18] and his forces have lost control of the situation there. Since the day of your father’s death the Crescentii have apparently been mustering their allies in the city. They have simultaneously been distributing bribes to influential Romans in anticipation of a propitious moment. Your departure for Poland provided them with the perfect excuse for taking action. Furthermore, the rumors now claim that you will later be journeying to Kiev, Constantinople, and even Ireland. Some have accused you of absconding with the entire contents of the Church’s treasury. The prospect of Romans starving while you and your friends tour exotic foreign lands seems real to many.

“I have been dreading the disclosure of the most shocking news of all. The Crescentii have brought to Rome John, the Bishop of Sabina, and they intend to depose you and quickly hold an election to install him on St. Peter's Throne. They may have already done so. At the moment your brother lacks the wherewithal to prevent this travesty. Your most loyal supporters have established a temporary headquarters in Saxo. From there we should be able to assess the situation and determine the best strategy for retaking the Throne of Peter as soon as possible. We all consider this coup a temporary setback. When we arrive at the castle, our agents will promulgate your excommunication of the pretender and his supporters.”

The baron and I departed on horseback. The baron’s steed, which the doge had provided, was no match for Maltempo, but even so we arrived at the castle in a remarkably short time. It surprised me not a bit that Tigra was waiting there to greet us, take our exhausted mounts from us, and assure us that the horses would receive excellent care. The young lady who greeted us on this occasion, however, differed markedly from the barefoot girl of my first visit. This time her hair was pulled back behind her head, and her feet were shod in elegant boots the color of sand. Her face seemed more drawn, and her features appeared sharper. She might have grown a little, but the most striking difference was in her carriage. She had previously dashed and galloped this way and that. Now she swept effortlessly in a stately manner from place to place. One thing that remained unchanged was the whip in her belt. She addressed us formally as before, but she could suppress neither her glowing smile nor the sparkle in her eyes. Her cheeks were flushed, and there was an unmistakable lilt in her voice. I am no expert concerning the moods of women, but I suspected strongly that she was pleased to see me, even in such dire circumstances.

The physical condition of my brothers appalled me. Octavian and Peter were still bedridden with injuries suffered in the confrontation with the rebels. Gregory probably should have stayed in bed as well. A bandage covered a huge gash in his forehead, a piece was missing from his left ear, his left arm was bound stiffly against his side, one eye was so swollen that it was probably useless to him, and he required assistance to walk more than a few feet. Nevertheless, he insisted on supervising the efforts to retake Rome, and no one gainsaid his right to command. Gregory’s voice was raspy as he greeted me, and it contained an uncharacteristic overtone of enthusiasm. The field of battle was clearly his element, and he relished every aspect of the challenge before him. He warmly thanked the baron for bringing me back so quickly.

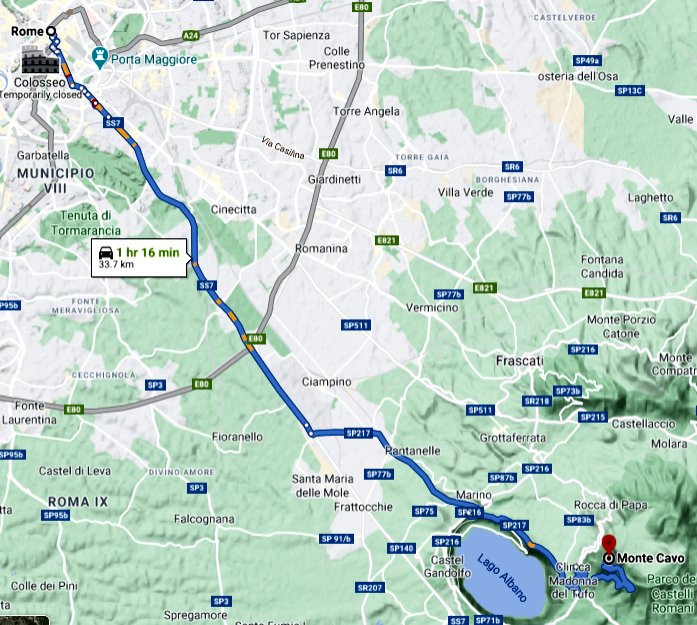

I set to work on the decree of excommunication. Agents were assigned to post copies of it prominently throughout the city and assure everyone whom they encountered that the Supreme Pontiff had temporarily relocated to Monte Cavo.[19] Furthermore, he—that is, I— was healthy, in complete charge of every particular, and in the process of planning the ouster of the usurpers.

Gregory asked me why, when describing my pilgrimage to family members, I had made so little mention of Baron Dubay, to whom he had taken an instant liking. I could think of no reasonable answer that was consistent with the version of events that we had agreed upon, so I shrugged and changed the subject by encouraging him to relate the details of the revolt and how he and my other brothers had suffered such severe injuries.

Gregory forthrightly admitted that a few of the guards posted at the city gates must have been deliberately derelict in their duties. He could not bring himself to call them traitors. He blamed himself for allowing such men to stand watch and for failing to unearth the plot in time to suppress it. Over the course of two nights the Crescentii had moved hundreds of their soldiers into Castel Sant’Angelo without arousing suspicion. At daybreak on the fateful day they had formed two groups. One overwhelmed the hopelessly overmatched pontifical force charged with defending the Vatican. The other marched on the Lateran. Our men fought bravely, but in the face of the enemy’s superior numbers, the defenders were forced to withdraw. My family and its servants had even recognized the necessity of abandoning Scuta and retreating to Tusculum.

Gregory considered this incident a personal failure, and he took responsibility for correcting his mistakes, whatever the cost. His contributions to the planning sessions in the following weeks were important, perhaps even vital, but the exertion drained him of energy, and only an hour or two of work repeatedly forced him to retire to his chamber to collapse of exhaustion.

Cardinal-Bishop Peter assured us that the bulk of the treasury was secure. Measures had been implemented years earlier to insure that papal holdings were never concentrated in a single location, no matter how defensible it seemed. A considerable amount of gold and silver had been lost when the Lateran Palace was seized by the rebels, but the caches of what he called the “drachmas” were intact. A matter of greater concern was the Church’s income. The portion that was derived from Peter’s Pence and other foreign sources was probably lost for the nonce. The rest depended on the loyalty of the agents responsible for local collections throughout the Patrimony. Peter’s assessment was that most would remain loyal, but others would procrastinate until they had a better idea of which side would prevail in the long term. Some could be expected to cooperate immediately with the enemy, especially if an enticing arrangement was offered.

I did not expect to see my former tutor, Brother Clement, in Saxo. The hegumen had sent him as his legate, and he was included in the planning sessions. I had had not seen Clement in several years, and the intervening period since our last encounter had certainly left its mark on him. His eyesight was poor, he was bent at the back, he moved very slowly, and his left ear had gone completely deaf. Nevertheless, his assistance in composing the edict of excommunication was valuable. He generally was silent during the tactical deliberations, but occasionally someone would ask him for the hegumen’s perspective. Brother Clement would then clear his throat and proceed to declaim solemnly some general principles that Hegumen Bartholomew had endorsed. He seldom addressed the specifics of issues.

How Brother Clement’s physical condition could have deteriorated so rapidly amazed me at the time. As I now cast my dim gaze on my own decrepit body, I wonder that it ever seemed unusual at all. An apple can rot in a day; a man can certainly degenerate in a few years.

Count Gerard’s contributions consisted largely of assurances that he could muster his men on short notice and that they could be counted on to accomplish whatever task was assigned to them. He insisted on personally leading them. In point of fact, the count seemed to relish his part in our quest. He seemed to grow more energetic and engaged with each passing day.

Tigra was not invited to the war councils, but her father occasionally summoned her to answer a question or to bring us something. I could not take my eyes off of her, and when she was absent, her image often crept into my thoughts, although not in an embarrassing way. After a week or so I found it difficult to concentrate on anything else for more than a short while. I was definitely smitten. Fortunately, after I issued the excommunications, no one expected me to contribute anything of value.

I arranged to spend my free time with Tigra. She showed me around the count’s estate. The tour even included a pair of secret chambers in the castle that she confided were known to no one else—not even her father. Although I was quite familiar with similar hideouts in both Scuta and the Lateran, I feigned amazement at these architectural marvels.

During our first days together she peppered me with questions and ideas about Homer and Virgil. She had obviously been eager to talk with someone about these stories. We both enjoyed these conversations immensely.

We also took rides together. On one frosty morning she meekly asked to take Maltempo out for a run. I feared that the stallion might be too fierce for such a small person, but I could not deny her request. My fear was groundless; I had underestimated her skill in the saddle and her ability to make horses feel comfortable. After a short period in her presence, Maltempo became familiar with her smell and touch. He apparently liked them as much as I did. Then she saddled him up, and off they went tearing across the frozen terrain[20] at full gallop. When they returned Tigra flushed with excitement. “Who would suspect,” she panted, “that the Holy Father would have such a magnificent mount?” She thanked me effusively for granting her the privilege of sitting on his back. I assured her that she could ride Maltempo whenever she pleased. In fact, she would be doing me a favor by providing the horse with the exercise that he needed while tedious affairs of my office commanded my attention.

Tigra started toward me with her arms akimbo, apparently intending to give me a warm hug, but she realized that others would certainly deem the gesture inappropriate. So, she rushed by me and hugged Maltempo’s right foreleg. At first he seemed a little spooked by this gesture, but when he realized who clutched him so tightly, he tolerated her presence and nuzzled her.

A few days later after a long ride Tigra and I were in the castle warming ourselves before a huge hearth. She remarked that my office must be very satisfying because I could always do whatever I wanted. This stuck me as both comical and ironic. I may have even snickered. That same day I had felt envious of her apparent autonomy in Saxo since her mother had died. In her environs she seemed make all the decisions.

I quickly disabused her of the notion that I had much authority in Rome. I explained that my deceased father had made all important decisions there, or he had exerted very strong influence on the others. When I was quite young he had arranged for my education, and he was the one who informed me that I was to succeed my Uncle Romanus as Supreme Pontiff. My intentions had no effect on policy decisions. Even when Count Alberic died, most important decisions have been made by a committee of advisers selected by him. My judgments counted for much less than the opinions of my brother Gregory, the more experienced cardinal-bishops, civic officials, and influential clergymen such as the hegumen. Even though I had held the office of Supreme Pontiff for over twelve years, I still felt like an impotent outsider.

My perspective shocked Tigra. She had assumed management of the servants in Saxo, but she considered it a burden that fate had thrust upon her. What frustrated her was her father never allowing her to leave the estate. She had never even seen Rome or Viterbo. Since her mother’s death only a few people had visited the count, and he had remained so melancholy that he seldom exhibited much enthusiasm or energy for anything. By and large he confined himself—and thereby his daughter—to the castle. She longed to see the rest of the world, or at least a little more of the peninsula.

Introducing her to the splendid tales of Homer and Virgil probably only made her feel worse about her situation. I wanted to express my sympathy in a concrete way, but I also needed to choose my words very carefully. I opted to describe the frustration and fascination of my relationship with Duke Casimir.

She was surprised to learn that my party had been on its way to Poland when the baron brought me back to face the emergency. I assured her that my role in recovering the city would be largely ceremonial. I confidently predicted that I would not be allowed to participate in the slightest way in military maneuvers. If everything went as planned, I would be informed when and how to enter the city. I would probably lead a procession through the most influential neighborhoods of the city, celebrate a Mass of victory, and sing the Te Deum. My every act would be choreographed to convince the public that the celebrations did not honor me or my family but the integrity of Holy Mother Church. I had no doubt that my days would once again be devoted to the mundane business of religious ceremonies, meetings, and audiences with the politically powerful punctuated only by an occasional lonely ride in the countryside. I failed to mention the singing lessons.

I trust that I have made it clear that Tigra was not bashful. At the end of my little speech she fixated on the word “lonely.” She asked whether I had ever considered getting married. I replied that priests, as she well knew, were not allowed to marry. Moreover, I had been informed when I was rather young about my role in the family’s destiny. In short, neither my family nor its supporters would allow my matrimony, even before I became pontiff. I summarized my fate with this sentence: “Before my birth the dice that determined my fate were cast by others.”

“What law forbids priests from marrying? Does Holy Scripture prohibit it?” she asked.

“I am not sure. I cannot recall anyone ever mentioning the idea in my presence. Why would they? I have no recollection of it being in the Bible either, but I surmise that it has always been the custom, if not the law, at least in the western Church. On the other hand, some apostles were certainly married. I am pretty sure that a monk at Grottaferrata once described married men in Constantinople who later became priests. That is, they were married first and then ordained. Apparently they were even allowed to live with their wives. I suspect that even in the eastern patriarchates once someone becomes a priest he is not allowed to take a wife.”

“If the Bible does not specify it, you could just change the rule, could you not? You speak for Rome, and when Rome speaks …”

“Well …” I could not keep my thoughts from wandering to the confrontation with Costanza some years earlier that had resulted in her bizarre request. As I thought of the number “ten” a grin must have appeared on my face. I forced myself to arrange my features in a scowl as quickly as possible. I could not tell if Tigra had noticed.

“Perhaps,” I continued, hoping to sound solemn and reflective, “but it would require a great deal of research to establish the groundwork required for such a ruling. The precedents dating back for one thousand years would dictate carefully considering the potential for popular outrage. I would never make a public pronouncement solely to demonstrate that it was within the Apostolic See's purview. My father taught us to choose battles carefully.”

Tigra looked at me for two or three heartbeats. Then she raised her eyebrows a little and smiled. She did not say another word for a considerable period. I spent the time gazing at the fire and weighing my own confused but exciting thoughts.

Only two weeks were required for my amazing brother Gregory to resume walking without assistance. Shortly thereafter Octavian had also recovered enough to join some planning sessions. As preparations for the counterattack took shape I argued forcefully that I should be in the vanguard of the assault. I asserted that I should be seen wearing my tiara and pallium so that the Romans would realize that the Supreme Pontiff was reclaiming what belonged to the Church. This rebellion was not merely the latest manifestation of an old feud between two families. I realized the futility of my words, but I yearned for adventure so strongly that the prospect of more fine men risking their lives for me repulsed me.

Gregory was obviously exasperated with me. “Look, you simpleton,” he began and then stopped himself. He took a deep breath, buried his forehead in his hands, exhaled, looked up again, and then continued with this: “Your Holiness must remember that the purpose of this project is to regain the Throne of Peter. We are all expendable, but if the Holy Father himself dies in the process, all the careful preparations, not to mention the casualties, will have been for naught. No, the only sensible course is for you to remain on the outskirts in a safe and inconspicuous location until our troops have secured the important buildings, driven the scoundrels from the city, and firmly established order. The plan requires you and the baron to stay incognito at an inn just outside the city until I personally bring word that you can enter. Then you can assure the citizenry that we acted on behalf of the Church, not the family.”

Despite that fact that it thoroughly annoyed me to be denied a chance for active participation, in this instance I could find no good retort. How could I dispute that it would be a futile gesture to chase the pretenders from the city if anyone other than the canonically elected pontiff sat on St. Peter's throne?

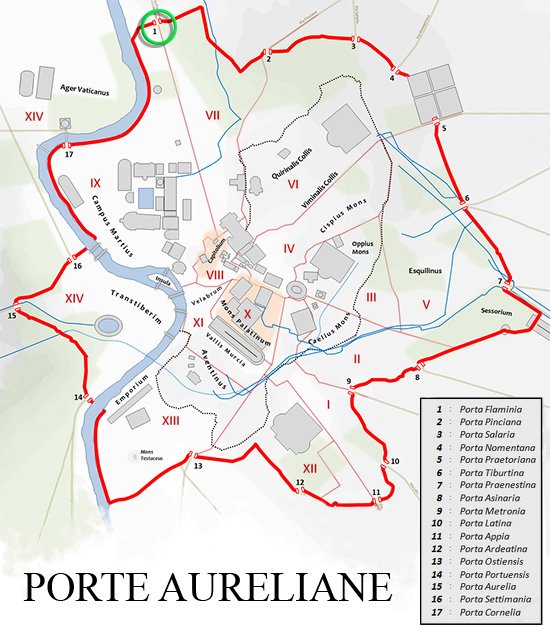

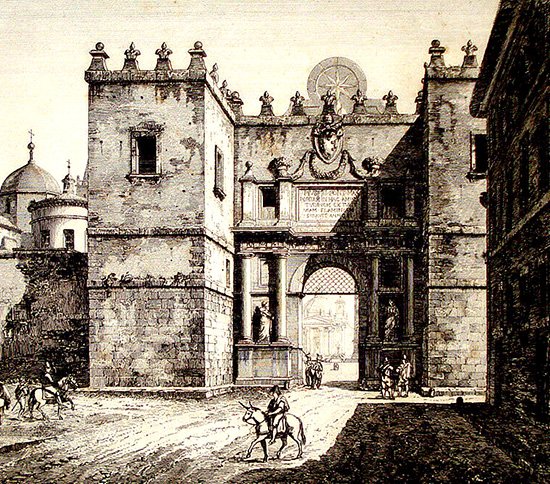

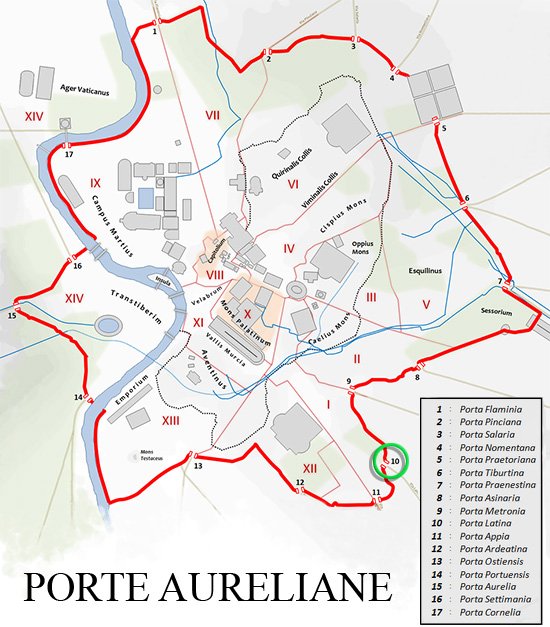

I therefore relented and asked Gregory to explain the details of their plan to me. He deferred to the baron. Our forces would amass under cover of darkness on the northeast edge of the city outside of the Porta Flaminia. Someone had already arranged for our agents within the city to overpower the guards there and to throw open the gates. Meanwhile incendiary diversions in other quarters would confuse the enemy and make it difficult to mount a coherent response. By the time that they discovered the nature of the attack, it would be too late.

Two days before the scheduled assault, a meeting was held to finalize the particulars of all arrangements. For the first time John Gratian, my godfather was asked to join us. He was introduced to the other attendees as a valuable contact inside the Lateran. Count Gregory asked Cardinal-Priest John to lead us in prayers, a role that he obviously relished. Then he described the situation in Rome. The new pontiff and his retinue had treated him well enough, but he could see that some officials were more interested in the aggrandizement of the Crescentius family fortune than in addressing important issues faced by the Church and the Patrimony. Every day, he said, he prayed for my return and the restoration of the legitimate Vicar of Christ.

Baron Dubay next showcased a plan entirely different from the one that he had presented to me. He explained that siege engines and ladders would be used to breach the Latin Gate. For logistical reasons the assault could not be scheduled for at least three weeks. Cardinal-Bishop Peter bitterly complained that his team’s access to crucial supplies had been blocked, and for that reason he reluctantly recommended postponing the attack for at least another week after that.

The baron seemed exasperated. He repeatedly emphasized how important it was that my pontificate be restored as quickly as possible. On the other hand, he understood the severity of the problems that they faced. He asked everyone to keep him and my brother apprised of their progress. Any delay would be costly, but a hasty failure would be catastrophic.

When Gratian had departed for Rome, the rest of us assembled again, and at this second gathering the wine flowed freely. One cardinal-bishop proposed a toast to John Gratian. My brother Gregory outdid him by suggesting that we honor “Gratian’s big mouth.” Confident of the archpriest’s willingness to disclose every detail of the phony plans to our enemies, everyone laughed and drank. My brother Peter performed an impression of Cardinal-Priest John leading us in prayer, and, to everyone’s gleeful astonishment, for once he was able to suppress his stammer. Three men fell from their chairs in raucous laughter.

As planned, the baron and I spent the fateful night in an inn just outside of Trastevere. Leo, its proprietor, had served my father faithfully for many years. He had been one of my father’s lieutenants until his vision deteriorated to the point that he could no longer function in that role. My father provided him with a loan to purchase the inn, which Leo operated with the assistance of his wife and two sons. The baron and I kept to ourselves in their establishment until Gregory burst through the door at about mid-day. He had just enough stamina remaining to display a wide grin.

“It could not have gone better. Half of the guards were drunk. Our men inside the city overcame them with little difficulty. The gates were wide open by the time that my troops arrived. We quickly routed what little resistance we encountered on the streets and recaptured both the Vatican and the Lateran. The survivors, including the usurper himself and most of his retinue, fled to Castel Sant’Angelo. We have already received correspondence from the Crescentii that Bishop John has returned to Sabina. Best of all, our casualties were minimal.

“So, don your tiara, pallium, and best papal vestments, saddle up that demonic horse, and let’s have a victory procession to acknowledge the return of my worthless brother as the Supreme Pontiff of the Church!”

Indeed, as our entourage majestically rode up and down the streets of Rome, the crowd cheered our triumphant return. I knew that many of the most vocal had cheered the Bishop of Sabina with commensurate enthusiasm just a few weeks earlier. The Roman populace always loves a winner, and for a short period he seemed to qualify.

Gregory and his men set to work reclaiming the pontifical residences and reestablishing order in the city and the papal territories. The process of repairing relationships with clerical and civil authorities brought a certain degree of satisfaction. It certainly kept me busy. The top priority was to assure our most important allies and potential allies that my pontificate had been restored and was firmly in command again in Rome. Short letters were also dispatched to both King Henry and the emperor in Constantinople, all of the patriarchs, the European bishops, the most influential abbots, and various kings and princes.

Hearings were scheduled for all those who had voted[21] to install John of Sabina as Supreme Pontiff. Two high-ranking clerics fled the city rather than face an official inquiry. The others groveled, apologized, kissed my foot, and pledged loyalty. I accepted no excuses; instead, I found all guilty, but I forgave them, absolved them of their sins, and allowed them to return to their duties. Gregory and several others advised me to order the public hangings of a few rebels as a signal that I would not tolerate this type of behavior in the future. I rejected such counsel. In my opinion killing a foe in combat was completely different from sentencing a man to death on the gallows for disloyalty. The first was an unfortunate necessity; the second violated the Decalogue. Perhaps I was wise, or perhaps I was just cowardly or squeamish. In any case, the Crescentii had suffered such a devastating setback that the family never recovered much influence.

As the weather improved in the spring I found it more difficult to keep my mind on my official duties. This was not the devil’s work, or, if it was, Satan had adopted a new set of tactics. My thoughts during this period continually returned to the treasured hours that I had shared with Tigra. My memory often replayed the smooth confidence that she always displayed in her treatment of underlings. When she was on the back of Maltempo or any other horse she was a sight to behold. My dearest recollection of all was her unbroken attention as I recounted the details of Odysseus’s clever plan to foil Polyphemus the Cyclops.

My last apparition occurred very early on Palm Sunday morning. At the foot of my bed stood the old bearded man with the big Keys. To his left was a grey-haired woman who bore a passing resemblance to a much older version of Tigra. She was a little taller than Tigra, but she was bent with age. She gripped the man by the elbow and gazed lovingly at his weathered face. I was incapable of movement in their presence. The man spoke to me in a friendly but solemn voice. “Theophylact, meet my wife and helpmate. I followed the Lord for my entire life, and she followed me. She introduced three saintly women into the world, and they now share with us eternal bliss in paradise. Without her I would never have found the courage to endure the persecutions or the wisdom to deal with the problems that beset the Christian community.

“You must make your own decisions, but never allow anyone to convince you that relationships between men and women always distract the faithful from their service. Married men serve the Church as faithfully as those who have chosen celibacy. The names of many virgins are on your list of saints, but I assure you that fathers and mothers who now reside in the celestial realm outnumber the virgins by more than one thousand times.”

Before they disappeared, the woman turned to me and smiled. The power of her gaze was almost unbearable. A small piece of heaven was transmitted from her face to my eyes. When I at last regained control of my body, I immediately got on my knees and fervently prayed at my bedside for nearly the length of a Mass. By the time that I pronounced the last “Amen” my face had been washed with tears of joy.

[1] Emperor Conrad II and Henry III’s wife Gunhilda died in 1039. Henry ruled from that point on, but he was not crowned as emperor until seven years later.

[2] St. Peter Damian’s writings concerning Pope Benedict IX were the most damning of any contemporary. At the time of Henry’s accession he was a Benedictine monk in the extremely strict hermitage at Fonte Avellana in the Marche. However, he was allowed to leave the monastery to preach. There is no evidence that Peter Damian was ever in Rome or the vicinity during the pontificates of Pope Benedict IX. During most of that period he was cloistered.

[3] Benedictus in Latin means “blessed.” Maledictus means “cursed.”

[4] Since the first half of the ninth century nearly all of Sicily had been controlled by a group of Africa-based Muslims called “Saracens” in this account. The last outpost of the Byzantines was ousted in 965. The Normans were not able to reconquer the island until 1091. By that time the Byzantines had abandoned the project that the author describes in this section.

[5] The Catepan of Italy was the Byzantine Emperor’s governor of the area of Italy south of a line from the Amalfi Coast to the Gargano Peninsula.

[6] A future King of Norway, Harald Hadrada, participated in this campaign.

[7] This is probably a reference to the leader of a group of Norman mercenaries named William de Hauteville.

[8] Emperor Michael IV the Paphlagonian.

[9] Vikings invaded Normandy in the tenth century and established settlements there. Within a few decades they had converted to Christianity.

[10] A Hungarian legend insists the Stephen was crowned by the pope himself in the year 1000, but there is no evidence of Sylvester II—or any other pontiff—traveling to Hungary in this era.

[11] Samuel Aba was a relative by marriage of King Stephen. It is not clear whether he was Christian, pagan, or even perhaps Jewish. He ruled Hungary from 1041 until 1044. His army was defeated by one led by King Peter and King Henry III of Germany. Samuel Aba died in the Battle of Ménfö. Peter’s second reign ended in 1046.

[12] King Henry III of Germany was not crowned as Holy Roman Emperor until 1046.

[13] There is no other record of such a letter.

[14] No correspondence between the imperial court and the papacy is extant.

[15] Pope Benedict IX’s appointment of thirteen cardinals in 1044 was unprecedented.

[16] At this time Venice was trying to reassert control over the Adriatic. By the end of the eleventh century the level of prosperity enjoyed by the Venetians would be almost unfathomable, especially in relative terms.

[17] If the author is correct about the year, the doge would be Domenico Contarini.

[18] The author's older brother, Gregory, who became count on the death of their father, Count Alberic.

[19] Monte Cavo is in the Alban Hills southeast of Grottaferrata. Saxo was actually north of the city.

[20] The reign of Sylvester III (John of Sabina) as pontiff lasted from January to February or March of 1045.

[21] Throughout the first millennium of Church history the process of selecting the pontiff was notoriously inconsistent. No details of Pope Sylvester III's election have survived.