After Mass on Palm Sunday I composed letters expressing gratitude to the nobles and clergymen who had actively supported the restoration of my pontificate. I invited them to bring their families and attendants to Rome to join our celebration of the Lord’s Resurrection. Although this year's rites would be particularly meaningful for us, I emphasized that we would observe the occasion in a solemn manner; there would be no raucous parties. Instead, loyal and valiant Christians would assemble in a demonstration of unity and comity. Couriers delivered the missives.

I entrusted my brother Octavian with arranging suitable lodgings for guests in the Lateran, Scuta, the Vatican, and elsewhere. Baron Dubay announced that his wife was joining him, but not in time for Easter Mass. I welcomed the opportunity to renew the warm friendship that I had formed with Ingetrude during our adventures together. The thought of seeing her again produced a feeling of blissful nostalgia.

Guests arrived all week. As I watched them become situated in temporary residences, my soul felt completely in harmony with the rituals of Holy Week in a totally new way. I had celebrated the the Mass nearly every day for more than a dozen years. For the first time, however, I genuinely looked forward to performing the sacred ritual prescribed by the Lord himself. The scriptural readings seemed to be speak directly to me and to address our situation.

By Thursday of Holy Week Octavian had welcomed nearly two hundred guests. I celebrated Mass that evening in St. Peter’s. I instructed my brother Peter to locate a dozen indigents and place them in a special section in the basilica. Just before Mass I knelt before each and washed his feet.[1] Then I did the same for the guests in attendance. I was delighted to see both Count Gerard and Tigra among them. His feet were large and horny. One toe was so misshapen that it was nearly perpendicular to the others. It must have caused him constant agony, but he never complained. Her feet, in contrast, were soft and plump; her toes were tiny.

On Saturday I offered to conduct a tour of Rome for Tigra and the count. She accepted immediately, but her father declined, which did not disappoint me. Tigra asked what it was like for the pontiff to appear in public. She fretted that people would recognize me or Maltempo.

How could I not have considered this possibility? Sometimes it seemed that Tigra knew more about me than I did about myself. I agreed to take a different horse; riding Maltempo in a city was almost a sacrilege anyway. I located the floppy hat that I had worn during my pilgrimage and placed it on my head. The final touch was a sling that I improvised for my left arm. No one in Rome would recognize this ragged specimen as the Supreme Pontiff.

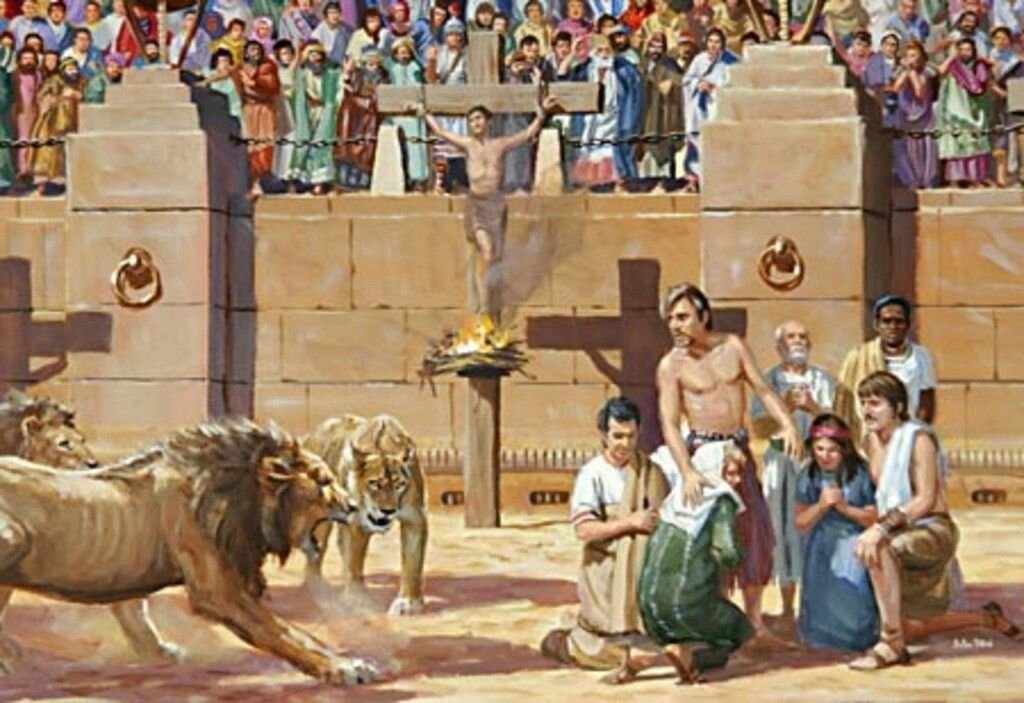

Tigra and I rode through the streets at a very leisurely pace. She had never been in a city. We passed imperial buildings that were abandoned long ago. She marveled at each one. We shared a light dinner in the shade of the huge ancient structure that now belonged to the church of Santa Maria Nova.[2] Even in its ruined state the majesty of the Colosseum stunned her. In recent years when materials were needed for new construction in Rome, the first thought was of this ancient site. Few Romans were even aware of its original purpose. Tigra was shocked when I recounted for her how Christian martyrs were used as entertainment for the pagans who ran the city. Even now I wonder whether she believed me.[3]

Throughout my pontificate I consulted with dozens of sagacious men; their advice probably averted several disasters. I valued their judgments as much then as I do now. For many years, however, I felt comfortable entrusting the details of my hopes and dreams to no one. As a youth I enjoyed exchanging whimsical ideas with my brother Gregory and my friend Gerard, especially when he was in the persona of Deacon Agatho. Later my relationships with both changed dramatically. They would certainly risk their lives for me; in fact, both had done so several times. At this point, however, their roles precluded their acting as my confidante.

Most men of my age could turn to their wives—or perhaps their mistresses—to discuss personal matters. Some probably engaged associates at work or sympathetic relatives. If none of their acquaintances seemed suitable, they could strike up a conversation with the proprietor of a pub. Most innkeepers have learned that a good way to sell wine or ale is to master the art of listening.

To whom can a Supreme Pontiff talk about his dreams? No one. In theory his power is unbounded—in his diocese, in the Papal States, and in all Christendom. He has dominion of sorts over all of these, but he has scant control over his own life and aspirations. Concerning those vast and baffling subjects his wise counselors are of little value.

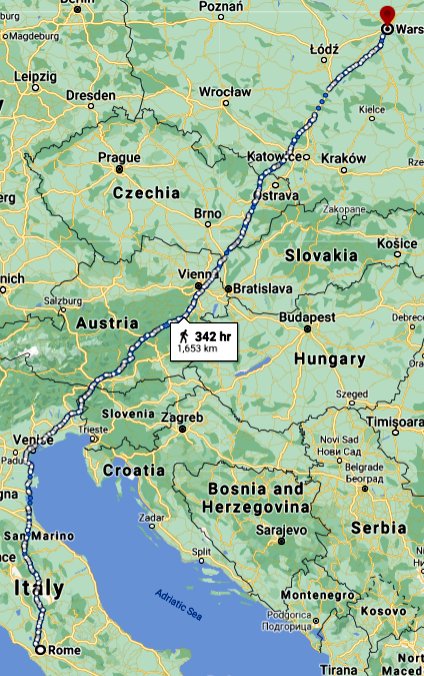

When a pope's aspirations are nebulous, as mine were for most of my pontificate, the lack of confidantes is not debilitating. However, my interaction with Prince Casimir inspired me to undertake a journey to Poland. The mission was a thorough failure. It had led to a disaster that was almost irreversible. Nevertheless, my desire to devote my personal talents and experience to spreading God’s Word remained as strong as ever. My mind realized that such an adventure might not be feasible for someone in my position, but my heart yearned for an opportunity to contribute personally to the Christian cause in a meaningful way.

As Tigra and I sat savoring our lunch amid the ruins of ancient Rome a life-changing moment seemed imminent. I had no plan to talk so freely with Tigra, but the words just seemed to flow from my soul and my heart without the usual restraints applied by the intellect. I heard myself describing details of my correspondence with Prince Casimir. I articulated how much I admired the young man's accomplishments, and I disclosed my desire to provide the support that he needed to secure his realm and reestablish Christianity. I explained how frustrating it was to deal with the quotidian responsibilities of my office in the comfortable and safe surroundings of Rome when I knew that the prince and his men daily risked their lives doing the Lord’s handiwork. I was elected as the leader of the diocese of Rome, the Petrine Patrimony, and the Christian Church. What sort of leader just sits back on his throne and prays that his subjects will carry the day? What sort of leader dares not leave his domain for a few months without risking everything for which he and so many others have toiled?

I asserted to Tigra that I was still a reasonably young man, and it was not too late for me to change the course of my life.[4] My career as Bishop of Rome had taught me how to deal with both churchmen and nobility. I argued that my presence and my efforts could help spread the message of the gospels among the Slavic peoples and the dwellers in the hinterlands in ways that no one else could.

“But Theophylact.” The two words shocked me, and my face surely betrayed my reaction. This was the first time that she had ever uttered my baptismal name in my presence. That she had practiced for this moment was evident. Residents of the Italian peninsula uniformly find the first consonant sound of my name extremely difficult to articulate, but her pronunciation was perfect. I was also touched by her choice of that name rather than Benedict. Needless to say, “Your Holiness” or “Holy Father” would have been completely inappropriate. She had seen me at my worst.

Tigra continued, “Like me, you have lived in this part of the world from birth. The customs of the people in those distant regions are probably as alien to you as were the ways of the inhabitants of the various islands to Odysseus. Perhaps more so. My father informed me that in some realms everyday hand gestures sometimes suffice to render one’s life forfeit. Think of that! I could not bear the thought of you setting out again with so little preparation and experience. As you indicated, your position is unique. If you perished or became incapacitated on the way to Poland, or even after you arrived, of what value would that be to anyone?”

Mindful that once the next set of words passed my lips I could never retrieve them, I paused to weigh my response carefully. The delay availed me nothing; on that day my heart, not my intellect, controlled my speech. “I am not quite as naďve as you imagine. I did not tell you everything that occurred in my youth. In the past—before I became pontiff—I undertook a long journey to distant lands. I have visited Jerusalem, I have seen Constantinople, and I have dealt with many strange people and faced a few extremely perilous situations. Furthermore, I have supreme confidence that Baron Dubay, whom I know from personal experience to be a man of unequaled competence in any situation in any land, would almost certainly accompany me on this quest if asked. If for some reason he was unable to do so, I harbor not the slightest doubt that he would provide whatever I needed to bring the adventure to a successful conclusion—advice, provisions, companions, contacts, etc.” I decided to change the subject before I blurted out too much out of vanity or foolishness.

“Let’s walk towards the hill,” I suggested. We gathered up the remains of our dinner and led our horses through the Forum toward the Capitoline Hill. As we strolled we shared a skin of wine, and I provided Tigra with as much information about the area as I knew. Our path took us past crumbling buildings and monuments from the imperial days overrun by weeds and vermin as well as churches, dwellings, and business establishments more recently constructed, in some cases using a substantial portion of the original sturdy structures.

I heard myself deliver a short speech that I never intended to make. “I realize that I have committed many horrendous sins in my life. I am deeply ashamed of them. Moreover, even when I feel that I am behaving properly, I seem destined to make mistakes that inflict pain and suffering on the ones whom I love the most. You have already experienced this, as I dare say that practically everyone who has ever associated with me has. It tears at my soul to admit this, but I see the disastrous effects of my actions everywhere that I look.”

I took a deep breath, let it go, and drew in another before continuing. “The worst of these failings occurred when I was a foolish young man, a few years before I was ordained a priest. The sin was so contemptible that I have never spoken of it to anyone, and nothing that anyone could say or do could persuade me to divulge the details. When it was discovered, I was called to account by the Holy Father himself. Can you imagine? The thought of having to face him mortified me, but the anticipation was much worse than the experience. He spoke gently and generously granted me conditional absolution; I was required to complete a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and he insisted that I leave immediately.”

She interrupted with a question. “This makes no sense to me. Why would the Holy Father deny you, his beloved nephew and designated heir to the papacy, the time and opportunity to prepare for such an arduous journey?”

“There was no difficulty in that area. Others made the preparations, and they were in all ways more than adequate. I can say no more than that, but my point is this. I was aghast that I had done such a disgraceful deed. In addition, the inevitable effect on my family—the most important family in all of Christendom!—caused me indescribable anguish.

“On the other hand, the punishment itself became for me the source of immense joy. In my youth I craved adventure and excitement with all my heart, and for nearly a year I realized many of my fantasies. The reality often exceeded my expectations. Of course, there were some harrowing moments that I would not care to repeat, and there were also quite a few disgusting and embarrassing incidents. For example, I quickly learned that my lifelong dream of sailing the seas quickly became, at the first sign of turbulent water, a horrendous nightmare. Just the thought of those miserable days on that ship renders me so queasy that even at this very moment I struggle to keep today's dinner in my belly.

“This is the fundamental story of my life: Whenever I did something horrible or made an egregious mistake, my family and its supporters immediately did whatever was needed to ameliorate the effects, or at least the publicly visible ones, in order to ensure that I fulfilled my destiny. At some point some of them decided that I was to become the Supreme Pontiff of the Christian Church. Ever since I was a boy, my path to the pontificate has been cleared by others. It was never my intention to study so much or to dedicate my life to God as a priest. Far from it: I would have exchanged places with any of my brothers in a heartbeat. My brother Gregory, for example, is doing exactly what he loves to do, and he is exceptionally good at it. It must be very satisfying for him. I spend all day doing what others want me to do, and I am so inept at it that over and over someone must clean up the odious messes that I have left in my wake.”

“I cannot understand why you feel that way. I have watched your brother Gregory, and he does not seem like a very happy person to me. He certainly must enjoy the companionship of the other soldiers, the excitement of combat, and the satisfaction of using his skills successfully. Nevertheless, anyone can see the pain and frustration on his face when he goes about his daily tasks, and he never seems to mention his wife or their children.”

A few of my most poignant moments—some with Gregory and some with Costanza—flitted through my thoughts. Tigra’s words only made me feel worse, but I had to offer some sort of explanation. “Gregory and Costanza have no offspring. She became pregnant years ago, but the child was stillborn, or at least that is what they told me.”

I cleared my throat and continued, “Do you really suspect that Gregory might not be happy? Ever since I can remember, I have idolized his skill at everything. He never seemed to botch assignments the way that I constantly did. He always was allowed to do exactly what he wanted to do. Everyone always admired him so. I feel certain that if he were allowed to choose any occupation in the world, he would choose the one that he has. Of course, he probably would select a different pontiff to defend.”

“How did Gregory and Costanza meet?”

I took a few moments to search my memory concerning their first encounter. I could think of nothing. I therefore replied, “I am not sure. One day my father announced at a big family gathering that they were going to be married and live in a wonderful palace that he was building for them.”

Tigra paused, tilted her head to the right, and frowned at me. I had come to appreciate that she did not always require words to make her points. I acknowledged her gesture. “Oh, I never thought of that. I suppose that you must be right. Maybe he has not always been free to do everything that he wanted.”

In a soft but insistent voice Tigra asserted “And I wager that he has made plenty of mistakes that your generous nature has overlooked as well. I suspect that your admiration for your brother has blinded you in many respects. You must never tell anyone that I repeated this, but my father informed me that your brother’s original plan for restoring your pontificate was not a good one. Father called it simplistic and foolhardy. He indicated that if the baron had not intervened to guide Count Gregory toward a more realistic approach, your exile might have been permanent.”

Her words astounded me. I knew that my brother had been seriously wounded at the time, and that may have impaired his judgment, which I had always found quite sound. I said, “I had no idea that anyone felt this way. You are wise and observant, Tigra. I suppose that I already knew that, but I am more impressed by your insights today than ever before. I need to ponder what you have just told me.

“But that will wait. This afternoon I wish to discuss my plans for the future. As I already mentioned, for years I have pined for the opportunity to do the Lord’s work in a more tangible manner. I would love to travel to foreign lands, to get to know the inhabitants, and to explain the wisdom and beauty of the gospels to those unfamiliar with them and even to those who have heard and rejected the Lord’s Word. I can only imagine what a thrill it would be if any of them came to me and requested baptism. Think of that—the satisfaction of providing a path to eternal salvation for people who otherwise would have no chance of achieving it. What could possibly surpass that feeling? Even if I only made my mark like that for a few months, the experience would bring a sense of fulfillment into my very soul.

“But no pontiff could ever do this. That I now see clearly. The Bishop of Rome is not like other clergymen. Most bishops feel free to vacate their sees from time to time in order to journey to Rome or anywhere else. I assume that trusted staff members tend to diocesan matters in their absence. My situation is very different. The Supreme Pontiff must address the needs of the faithful in the Holy See just as any other bishop must mind his diocese, but the pontiff’s responsibilities also include serving as final arbiter of disputes over Church matters and as the overseer of the patrimony. Unlike other bishops, the pontiff is a prisoner to his job. I have recently learned that painful lesson. I have heard legends of a few pontiffs who traveled outside of Italy,[5] but none in memory ever engaged in missionary work. My father absolutely prohibited me from embarking on such a journey, and now I understand that, as always, his decision proved to be completely justified. As soon as I departed from Rome, chaos erupted. I never even left Italy. Can you see why I feel trapped?”

“Yes, of course,” Tigra answered. “But I feel strongly that you are much too hard on yourself. You recognized in Prince Casimir the traits needed to prevail in his cause, and you arranged for the support that he needed. You did not fail in this endeavor; you succeeded admirably. His success reflects your persistent efforts.”

“Well, my decisions may have had some effect, but the ultimate triumph belonged to the Prince. I did not even learn about his victories—nor his losses and travails, for that matter—until more than a month after they occurred. We all certainly took some pride in our involvement in his undertaking, but any pontiff could have easily done what I did. In comparison with his, my deeds were small and—most importantly—impersonal. I conquered no heathens, and I never convinced anyone that the Christian way was the only viable path to eternal life; I merely had Cardinal-Bishop Peter direct some funds to Poland, and I wrote a few letters. There was no direct personal involvement at all. I cannot point to even one Pole and say, ‘I, Theophylact, helped this man to become a faithful Christian. I showed him the path to salvation and convinced him of the rectitude of Christian teachings.'

“In all honesty I cannot even say with certainty whether our support helped or hindered Prince Casimir’s cause. I presume that it did some good, but we in Rome are so removed from the scene that there is no way for us to know for sure. I have learned in my long pontificate that good intentions do not guarantee good results. As often as not, a seemingly righteous approach proves to be counterproductive. Political relationships are complex, too complex for my reckoning. I have no aptitude for politics. I much prefer to deal with individuals on a personal basis. At least, I think so. I have never really had much opportunity to find out.”

As we passed the House of the Vestals, I explained that this structure had been used by church officials as recently as the previous century. Since then it had been ransacked for construction materials. That part of the story was not surprising to Tigra, but when I told how the ancient Romans had used the building in the days of the Caesars, she was clearly shocked. In fact, I suspect that she thought that I had concocted the tale in order to provoke a reaction in her.

We then strolled past two projects that I had directed the Church to fund. One was a dormitory designed for monks who were in the city for pilgrimages. Nearer the Capitoline Hill was a palace that was being constructed for Cardinal-Bishop Peter’s official use.

I suggested to Tigra that we climb the Capitoline Hill and take in the stunning views available at its summit. We could have mounted the horses for the climb, but it was easier to talk while we were on foot. The ascent seemed not to wind Tigra at all even though the path was steep, and she required three or four strides for every two of mine.

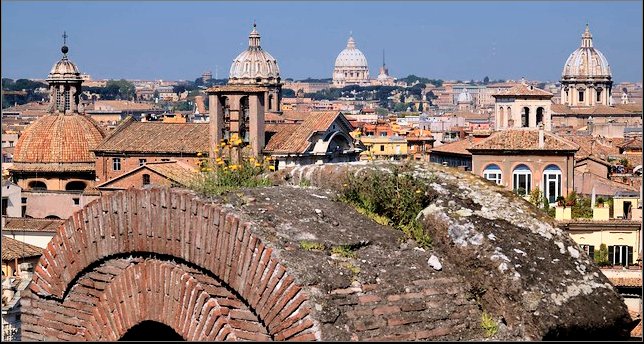

On the summit we looked back on the Forum, the Colosseum, and the remnants of imperial Rome. We kept our thoughts to ourselves, but we shared a smile. We then turned around and directed our gazes toward the Vatican and Castel Sant’Angelo, clearly visible over the fields and the roofs of the modern city. We squinted at the breathtaking beauty of early spring colors enhanced by the late afternoon sunlight.

“Rome today remains a rather impressive city in some ways, but how it has been allowed to decay!” I pointed to dilapidated structures on all sides of us that had been abandoned for centuries and were covered with dirt and detritus. “I have heard that at one time it was home to forty or fifty people for every living soul who resides here today. Just think of that!”

I paused while I considered what to say next.“I could stay in Rome and devote my time and energy into reviving and rebuilding the city. If my title were Roman Emperor, or King of Italy, or Senator, or Patrician of Rome, that would a worthwhile endeavor—if I could find some way to accomplish it. But I have not been assigned those roles, and neither my talents nor my passion lie in those directions.

“I was elected by the senior clergy as Bishop of Rome. Therefore, I must simultaneously play at least three different roles.” I counted them off on my fingers. “As bishop it is my responsibility to advance the faith of every Christian who resides in the Holy See. That is, frankly, an easy job. I am blessed with dozens of assistants, and there is a surfeit of churches that provide the faithful with both inspiration and solace. No Roman Christian complains of lack of access to the sacraments, and countless devout priests and monks in the city are willing and able to educate the public about Christ’s teachings. They require no help or guidance from me.

“My second role, on the other hand, is one for which I am unqualified both in experience and temperament. Every pontiff is charged with maintaining the defense, integrity, and welfare of the papal territories. I have placed my trust in my brother Gregory and my counselors in this assignment. I go where they tell me to go, and I do what they tell me to do. I have tried to make sense of the world that they describe to me, but I am quite certain that I could never perform this job without their wise advice. Up until now this arrangement has worked out well. My pontificate has been relatively peaceful, and by and large the people who live in the Petrine Patrimony, except, of course, for our traditional enemies, seem satisfied with the results.

“In my opinion, the third role should be paramount. The Bishop of Rome is, as all concede,[6] the Vicar of St. Peter. The pontiff inherited from the apostles the awesome and sacred responsibility of extending the message of Christianity to all of mankind and fortifying the faith of Christians everywhere. My uncle Theophylact’s great achievement was the expulsion of the Muslims from Italian soil. His accomplishments have always inspired me. Yet there is so much more to do, and now the most important work, in my judgment, is far from Rome. In a way Pope Benedict VIII had an easier task; the enemy then was easy to recognize and was close at hand.

“That almost anyone could successfully play the first two roles is revealed by a cursory examination of the pontificates that preceded those of my uncles. Moreover, I have concluded that no one can simultaneously succeed in all three aspects of the papacy. Any pontiff who really dedicated his life to spreading the word of God would inevitably become, or at least appear to become, an irresponsible ruler of the papal territories and probably an inattentive bishop. Perhaps that is why almost no pontiff since Peter himself has even tried to travel and convert unbelievers in person.”

I thought better of what I had just said. “I probably claimed too much. Perhaps men have lived who could juggle all three roles. Perhaps somewhere in Christendom is another genius of the magnitude of Pope Sylvester II or Leo the Great.[7] I know too little of the history of the papacy and the nature of such men to judge for certain.

“I am, however, well aware of my own shortcomings. On every occasion that I have striven to become a more vigilant and vigorous leader of the Christian Church, a disaster or near disaster has befallen me and everyone around me. The conclusion, it seems to me, is indisputable. If I desire to accomplish anything important for the Christian Church—and I most certainly do—I must somehow free myself from the invisible shackles that have hobbled my ankles since the day that the pontiff’s tiara was placed on my head.”

Tigra stared intently at me. My eyes seized her gaze and held it. I took a breath. She took a breath and then asked, “It sounds to me as if the grand plan for your life is merely to quit your job and avoid your responsibilities. Is that right?”

“I would not state it that way. In the first place I have no grand plan. I am just a frustrated man with the seed of an idea that I have discussed with no one.. To me it seems much more like a beginning than an ending. I want to start the truly important part of my life. The only way to do that, as far I can see, is to terminate this miserable career that other have forced on me.”

“Has any pontiff ever done this?”

“I do not know. I am not sure if anyone knows. I do not care a great deal about whether there is a precedent. At this point I care to the depth of my soul about only two things. I want to accomplish, or at least attempt to accomplish, something important with whatever time, talents, and energy the Lord has granted me, and I want to be with you for the rest of my life.”

Tigra abruptly sat down on the soil. She rested her elbows on her knees, and she placed her head in her hands as if it were weighted down by such ponderous thoughts that her neck could no longer support it. I seated myself a foot or so from her, and I gazed at the western horizon in silence. After an uncomfortably long silence I resumed speaking.

“I feel that I know you, but then again I really do not. For example, I recall that you told me that you were dissatisfied with your life with your father, but I cannot remember you ever telling me what you would prefer to do. What are your dreams?”

An even longer period elapsed before she raised her head a little and looked at me. Tears were streaming down her cheek. In a tremulous voice she announced, “This conversation must cease immediately. I sense that you must be sincere, but this overwhelms me.”

She looked down at her feet before continuing. “You are the Vicar of Christ! I cannot speak with you in this way. Please direct me back to my quarters. I will find my way alone. Just point out the roads to arrive there.”

I was crestfallen, but I did as she asked. It was probably unnecessary to give directions. Her horse almost certainly knew how to return to the Lateran Palace.

My words had burst forth from my heart without passing through my mind. As I sat by myself on the Capitoline Hill, I realized that I had devoted far too little thought as to how those words would fall on her ears. To be honest, I had actually dedicated no thought at all to the effect on her. Something that I said had evidently hurt her deeply, but I did not know what. For my entire life women have mystified me. This episode was perhaps the clearest of many examples of my abject ignorance of their nature.

I had been as resolute as ever in my life when I described my intentions, but from the moment of her departure from her seat next to me on that hill I completely lost my bearings. Not knowing what to do, I reverted to a state that I knew well. Pretending that nothing had happened, I simply performed the duties of my office as attentively as possible. I said Mass in St. Peter’s on Easter Sunday, and I noticed in a vague way that my relatives and supporters were in attendance. I blessed both the food and the participants at the Easter Supper that was held at the Lateran Palace. I partook of the feast, but for the most part I avoided participating in the lively banter at the table. I cannot precisely remember what I said. Perhaps I was silent. Afterwards I repaired to my apartments where I spent the evening in prayer and contemplation. Only when I lay in bed did I let the scenes with Tigra replay in my memory. I must have slept that night, but only a little.

On Monday morning I left my chambers early and celebrated Mass at dawn in my private chapel. Only one person attended, the Count of Saxo. After the dismissal[8] I changed from the priestly vestments to my usual garb. As I emerged from the sacristy, Count Gerard accosted me. He stood stiffly, but small movements of his hands and face betrayed his distress.

“Holiness, my daughter’s spirit is crushed. She left with you on Saturday, but she returned alone. Do you know what brought her to this state? Please help me in this matter. I am at my wit's end. I have never seen her so unhappy. Even her mother’s death had less effect on her.”

I seated myself and motioned for the count to do the same. He was a valuable ally. I tried to imagine how my father or my brother would handle the situation. It was futile; obviously neither would have ever been involved in such an imbroglio in the first place. Words similar to these found their way to my lips: “I shared my dreams with Tigra, and I asked her to share my life. It was an unforgivable blunder on my part. She was so overwhelmed that she left me sitting on the Capitoline Hill without a fare-thee-well.”

“Are you saying that you asked her to be your wife?”

It was certainly a reasonable question for a father to ask, but in truth this aspect had never entered my thought process. Nevertheless, I uttered three short sentences with little hesitation, “I did not use that word. I did not get that far in explaining my plans. I would if I could.” The last short sentence I said very slowly.

“No pontiff can take a wife,” he grunted. He continued after a short pause in which he regained his aplomb. “Please excuse my abrupt manner, Holiness; this matter is completely beyond my ken.”

While he spoke he had been passing his hat from one hand to another in obvious frustration. “My intention was to resign as Supreme Pontiff, and I told her that much, or at least I implied it so strongly that she must have understood. Maybe my failure to be clear on this point is what upset her. I do not know. She said very little; she just departed.”

The count sat motionless for a period. I could not ascertain whether the thoughts burning behind his penetrating gaze and his furrowed brow were the result of intense anger, but I suspected as much. In any event, he composed himself, stood, and said simply, “Thank you for your time and your candor, Holiness. I will speak with my daughter.” He was a man of few words.

After Monday's midday meal I received a message from my brother that my presence was requested at an important meeting after the bells at Sext.[9] The messenger waited for my reply. I anticipated that the proceedings would be unbearably embarrassing and stressful. Nevertheless, I had chosen my path, and I knew that I must now take the first step on it. I informed the messenger that I would attend.

When I arrived at the designated chamber, my brother Gregory, Count Gerard, the hegumen, and two cardinal-bishops were already seated. Cardinal-Bishop Peter and Baron Dubay arrived shortly. The hegumen, who seldom contributed much to our discussions, welcomed everyone in a somber voice before addressing me directly. “Holiness, Count Gerard has disclosed extremely disconcerting news to us. Could you please clarify your intentions?”

I had rehearsed my answer to such a query. “I feel tremendous gratitude for everything that everyone has done for me. I am serious when I say that I feel that I am in no way worthy of your efforts. I have always considered myself inadequate to my assigned task of protecting and extending the marvelous work of my two predecessors. Most of you no doubt agree with that assessment. Recently I have determined that it would be folly for me to continue in this manner any longer. Instead, I hope to embark on a new life that better suits my interests and my talents and takes advantage of the unique experiences that I have amassed. I wish to journey to Poland and the other Slavic lands to help Prince Casimir and like-minded individuals spread and buttress Christianity among those people. I have asked the count’s daughter to accompany me.”

A thick silence greeted this burst. Then my brother smirked, “This is just like you. Some romantic idea worms its way into your skull, and you immediately decide to upset everything for everyone to act upon it without even a slight concern about how it would affect the rest of us, not to mention how ridiculous you would look. I just …”

He could not finish his thought without pounding the table so hard that the room shook. Everyone flinched.

The hegumen’s massive forehead seemed to add another line or two of wrinkles. He spoke more softly than my brother, but his tone was even firmer and more derisive. “This cannot be. The stakes are too high. All Christendom depends on you. No. Never.”

After an uncomfortable pause the baron spoke next. His tone was neutral, as if he were asking about the weather. “Holiness, let us make sure that we all understand your intentions and expectations. Do you plan to marry Tigra?”

“That would bring me great joy. I acknowledge that it is impossible under the present circumstances.”

“And therefore you plan to resign as Supreme Pontiff?”

“Actually I viewed the resignation as a necessary condition for my planned missionary work, but I now also see that it was required for the marriage. So, yes. Certainly, yes.

“I have long felt that others would be much more capable than I have been in playing the role of pontiff. Cardinal-Bishop Peter or the hegumen, for example, have much greater aptitude in all matters pontifical than I do.”

“I see. And this expedition to Poland—how do you propose to finance it if the Church does not support the idea?”

The question startled me. I beheld the stern faces on every side. I had until that moment given no thought to the funding of my plan. Having worked closely with Cardinal-Bishop Peter for many years, I had a basic understanding of financial arrangements, but I had never needed to raise capital on my own behalf. Peter always handled it. Furthermore, I had little or no wealth of my own; Gregory inherited the estate from our father. I ruefully admitted that I had not yet given much consideration to that aspect of my plan.

“Would you expect the count to provide for your expenses on this adventure?”

“Of course not. Such an idea would never occur to me.”

“I feel certain that that much is true. It was important for all of us to hear you say it. What you have told us is simple in concept, remarkably simple, even laughably simple. However, we all foresee complex and worrisome ramifications. You are aware of some of them, but I suspect that others may not yet have occurred to you, or you may underestimate them.

“Furthermore, as far as any of us can determine, your stated course is totally without precedent. No one anticipated this, and at this moment we are all extremely anxious. I think that the group needs time to digest this news lest someone give vent to visceral reactions that he may regret later. Let us provide our minds and souls with a chance to weigh alternatives before we let loose what we can barely contain from bursting forth from our hearts.

“Here is what I propose. All assembled here have an abiding interest in your future. Everyone here wishes you well, and no one desires to see you unhappy or frustrated. Others are also deeply involved, but this group is a representative sample. I ask, Holiness, that you leave us now so that we can frankly discuss this issue privately for the remainder of the afternoon. Everyone, I feel certain, will feel much more comfortable about expressing their opinions if you are absent. Then, if everyone agrees, we can reconvene after supper. Does the Holy Father agree to this plan?”

“Certainly.” I would have agreed to almost any plan that included the termination of the interrogation and my quick departure. My palms were bathed in perspiration.

The baron continued, “Good. Do the rest of you agree?” My brother’s muscles were tense, and he appeared ready to grab me by my skinny neck and beat some sense into me. Nevertheless, he and all present solemnly nodded in concurrence.

I never learned the particulars of their discussion. When I rejoined them several hours later, the hegumen spoke first. “Holiness, I alone dissented from the decision that has been reached this afternoon. The baron has devised a clever plan, and he defended it against all objections with consummate skill. His judgment may well be correct. I can cite no flaw in his reasoning. Nevertheless, I feel strongly that you, Holiness—and only you—are the best hope for leading the Church through the trials that it will face in the coming years. These years will likely determine whether the Church as we know it survives. I have long been convinced of this. I feel strongly that your proposed actions are self-centered and short-sighted. I fear that horrible consequences will inevitably follow your resignation. For a thousand years the Church has faced one dire peril after another and returned stronger each time. I fervently pray that the Holy Spirit can guide us through this crisis, but I expect the worst.”

The hegumen’s words struck me with the force of a bullwhip. My brother added this, “I agree with the hegumen that you are both selfish and unbelievably naďve. However, the baron has proposed a plan that satisfied everyone’s objections. He will explain the details.”

The baron wasted no time. “We began with the judgment that you are stubborn enough to resign even if everyone in Christendom opposed it. Perhaps your father could have convinced you of your folly, but none of us is suited for the task. Therefore I propose the following.

“First, you will swear to us not to announce your intentions—or even to mention them to anyone outside of this room—until the first phase of the plan is complete. During this period Count Gerard and his daughter will repair to Saxo, where he will determine if Tigra is amenable to your scheme. He has agreed to portray your missionary idea in the best possible light. If she does not agree, we will provide you with an opportunity to convince her yourself. I have very little doubt that she will eventually succumb. The look in her eyes is unmistakable.

“Meanwhile, we will offer support for the election of your godfather, Cardinal-Priest John Gratian, as the next pontiff. The negotiations will include representatives from the Crescentius family. This part will be difficult, but we will insist that the Church under the new pontiff completely fund your mission to Poland for as long as it takes. We will obtain assurances that sufficient funds are set aside for this purpose in a manner that cannot be later countermanded. Cardinal-Bishop Peter and I will negotiate the details of providing for your excursion. We have other conditions, as well, but you need not concern yourself with them at this point. I am rather confident that Gratian will seize the opportunity that we offer. Moreover, his closest advisers, I suspect, are even more ambitious than he is.

“When the negotiations have been successfully concluded, you will call a synod of the bishops, cardinal-priests, and cardinal-deacons to announce your resignation. A few will be shocked at the news, but we will have arranged enough votes to assure both the approval of your resignation and the election of John Gratian. Your supporters have ample experience and expertise in these matter. No one will object as vociferously or eloquently as the hegumen has for the last few hours. A considerable number of the gentlemen involved were quite pleased to see you removed from office only a few weeks ago.

“After you officially resign you will be a free man. You may schedule the wedding and your departure as you wish.”

I suppose that I should have expected something like this. It was consistent with the rest of my life. At no point was I was even consulted as to my thoughts about the plan and its implementation. Like every other important decision in my life, this one was made for me. At the time, of course, I felt mostly excitement, joy, and, more than anything, relief.

[1] The earliest previous reference to the Maundy Thursday custom dates from the twelfth century. In most cases thirteen indigent people were selected for the washing, not twelve.

[2] What is now known as the Colosseum in the Middle Ages was on the grounds of this church. Over the centuries several feet of dirt and silt from flooding had collected there and in the Forum area. By the eleventh century some interior sections became the site of a housing development as well as a market of sorts.

[3] Most present-day historians also discredit many of those stories.

[4] If the dates provided in Chapter 1 are accurate, then Pope Benedict would be approximately thirty-three years old during what is now considered his second pontificate. That, of course, is a very young age for a pontiff.

[5] Pope Stephen III (IV) definitely traveled to France in 753 to beseech Pepin to bring the Lombards to heel. A few other pontiffs of the first millennium may have undertaken short trips for political or diplomatic purposes. Several were forcefully removed, and a small number abandoned the Holy See (and even Italy), but the idea of a peripatetic pontiff is a relatively modern one.

[6] It is not clear at this point in time that the Eastern Church actually conceded this point. The Great Schism occurred only two decades in the future. Easterners often called the Roman pontiff “first among equals.”

[7] Pope Leo I reigned from 440-461. Among many other thing, he is credited with persuading Attila the Hun, whose massive army was encamped in Italy at the time, to leave the peninsula without advancing on Rome.

[8] The last words of the Mass, “Ite, missa est”, are pronounced by the celebrant.

[9] Noon.