After meeting with the hegumen I lingered in Rome for a few days. Our group visited famous churches and shrines. I avoided drawing attention to myself; no one seemed to recognize me. We then returned to Canossa, where I resumed my placid life.

Every week or so the margrave updated me on the situation in Rome. He also shared intelligence about political relationships in Italy and beyond the mountains. My memory for such matters is even less trustworthy than my faded recollections of people and events that interested me. I apologize for this failure and for the fact that my knowledge of subsequent years was largely shaped by much later conversations with people more attentive to the facts. Since I personally partook in few of the events, I am less certain of the details than I am about what I have already related. Nevertheless, my narrative would be laughably incomplete without a chronology of papal history during this crucial period. I therefore feel compelled to record my impressions of these years.

I start with one recollection that remains quite vivid. On one of autumn's first chilly days[1] the margrave summoned me to his parlor. He said that he had received word that King Henry was crossing the mountains into Italy. His sources reported that Pope Gregory—my godfather John Gratian—had invited the king to Italy and offered to crown him as emperor. This news astounded me, but the margrave assured me that the king's presence would probably not impede the activities undertaken by my supporters, which were, he insisted, proceeding apace.

A few days later I learned that the king’s party had reached Verona, and King Henry had publicly announced plans to visit Rome. Along the way he held court at Pavia. The Toad, on Pope Gregory’s behalf, had chosen that location to finalize arrangements by which the pontiff would crown Henry as emperor. Margrave Boniface did not say how he learned about this encounter between the Toad and the German king. Perhaps he had a network of informants; perhaps my brother, Count Gregory, relayed the information to him.

When King Henry asked the Toad to evaluate my long pontificate, the little monster ignored its many accomplishments. Instead, he repeated the worst gossip and rumors that my brother previously disclosed. Some accusations were even more outlandish than what my brother listed. The dwarf claimed, for example, that a brothel operated inside the Lateran Palace.

The king then asked the Toad's opinion of the usurper known as Sylvester III. The Toad, brazenly claimed that he, who was not even a priest, had been chosen to speak for clergymen working to reform the Church. He reported that no reformer supported the pretender from Sabina. His family had obviously seized the papacy through force of arms, and, even after he had assumed control of Rome and the Church, he had failed to garner support outside of the Crescentius family and its minions.

Oh, to have been present for the next exchange! The king showed little interest in Pope Gregory’s support among the clergy and the Romans, his political or ecclesiastical leanings, or his plans for the future. Instead, the king demanded details concerning John Gratian's unusual—in fact unique—route to the papacy. The king apparently knew many particulars of the agreement negotiated by our representatives and Gratian’s. Faced with the well-documented accusation that Pope Gregory had committed an act of simony, the slimy Toad insisted that Pope Gregory was against providing monetary support to me. Much debate and prayer led him to conclude that it was the only way to wrest the papacy from my family’s control. The other reformers agreed that the opportunity to elect Pope Gregory was the best hope of implementing reforms.

The king scoffed at this self-serving justification. A few days later he announced his intention of calling a synod at Sutri[2] to resolve the situation.

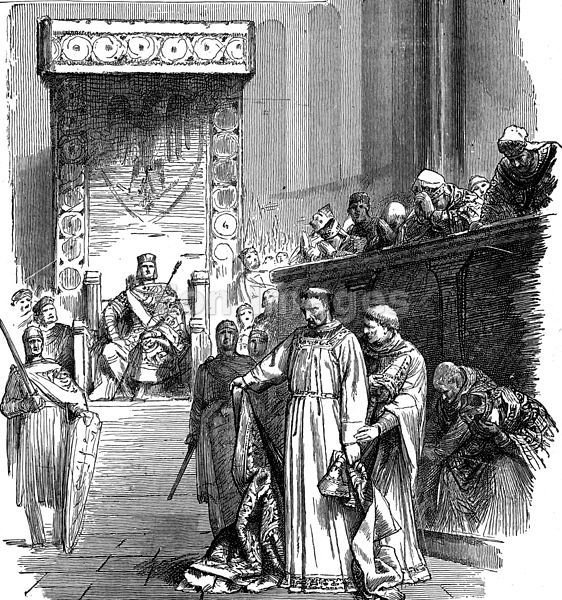

Much later I learned that the king had sent a letter to me in Tusculum that summoned me to Sutri to answer the charges against me. Evidently the Bishop of Sabina received a similar missive. Neither of us responded. The margrave later assured me that the synod had been a farce staged by and for the king, who positioned his troops so that the clergy who attended were bound to be impressed by their might and proximity. They meekly voted for all of the king's particulars. They began by declaring both me and the Bishop of Sabina deposed, actions that were at once peculiar and superfluous. How could anyone argue that Bishop John was anything but a usurper?[3] I, on the other hand, had voluntarily resigned. Whether the council judged me to be the legitimate pontiff was immaterial. The council took one important step. It advised Pope Gregory to resign in disgrace, and he complied.

King Henry then proposed a German noble named Suidger, whom he had previously invested[4] as the Bishop of Bamberg,[5] as the Bishop of Rome. It is hard to write sensibly about this. How could any reader grasp the notion that Roman clergy had decided that the solution to Rome’s alleged problems required seating a barbarian from Germany on St. Peter’s Throne? Nevertheless, it came to pass. Under duress an assemblage that was in no sense canonical selected a foreigner who was unqualified for his new assignment and specifically prohibited by canon law[6] from holding the office. How could any Roman think that he was the legitimate Vicar of Christ? The pretender, who took the name Clement[7], immediately crowned his liege Henry as emperor. He then abandoned Rome to follow the king, Pope Gregory, and the Toad back to Germany! Gregory was held there as the king’s prisoner and, in fact, never returned to Italy. The whole affair defies belief. Yet it was only the first of many such outrages.

The next event that I remember clearly occurred after only a few months had elapsed.. When I entered the margrave’s chambers for a briefing, I was shocked to see my brother seated at the margrave’s side. Gregory greeted me as curtly as when he had supervised my training. “Shave your beard, Theophylact, and trim your hair. The time has come. Pope Clement has died, and you are returning to Rome.”

The margrave supported the project both spiritually and materially. He contributed an impressive contingent of well-trained and well-equipped soldiers. My brother Gregory and I led the force south to Rome and reclaimed the city and the papacy without encountering any significant resistance. Evidently neither the Crescentii nor the supporters of Emperor Henry III anticipated a rapid deployment of such a large force.

Most of the Crescentii, expecting us to exact vengeance, fled the city. I forbade such a reaction. I did not excommunicate anyone, not even the monks who had slandered me in public. In a spirit of clemency and accommodation I acknowledged and ratified all of the conclusions reported by the Council of Sutri except, of course, the lies concerning my behavior. Since John Gratian’s method of obtaining the papacy had been judged illegal by the council, all his declarations, including those that released me from my vows and accepted my resignation, were voided. The council had removed all impediments to resumption of my pontificate. No ceremonies were needed, and none performed.

Everyone involved in restoring my pontificate acknowledged that my old friend Baron Dubay had been the principal designer of the triumphant strategy. His ability to manage such a complex situation and his impeccable timing were critical to our success. Unfortunately, circumstances prevented him from accompanying us on the march south, and so he was not in Rome. Important issues in Alsace required his attention. The baroness accompanied him.

As soon as I had retaken the Throne of Peter I sent word to Constantinople concerning the death of the German usurper and the return of stability to the western Church. I emphasized that the man who claimed to be pontiff had seized the office illegally backed by the King of Germany's threats. The clergymen who had voted at the synod called by the same king in Sutri had ratified this coup under duress. I expressed my desire to resume working closely with the patriarch and the emperor[8] to continue the mission of spreading the gospel throughout creation.

A few months later my brother’s sources reported that my family's enemies had gained King Henry's ear. They encouraged him to act swiftly to replace me with a new pope, and they agreed to abide by his choice. They also emphasized how important it was that the Bishop of Rome reside in the city and interact with the people there. The deceased usurper paid little attention to Roman matters. Henry eventually settled on a man named Poppo, who had been serving at the king’s pleasure as Bishop of Brixen.[9]

The king sent Poppo to Tuscany with written instructions for the margrave, who was a vassal to Henry as the titular King of Italy. The orders specified that Boniface must deploy his forces to drive me and my retinue from Rome and install Bishop Poppo as Supreme Pontiff. The margrave made it clear that this scheme was nefarious and illegal, and he refused to participate.

Poppo returned to Germany and reported the margrave’s recalcitrance to Henry. The emperor then sent to Margrave Boniface a strongly-worded letter in which threatened to return to Italy with his entire army to oust the margrave from his hereditary holdings if he did not immediately take all steps necessary to install Bishop Poppo on St. Peter’s Throne.

The margrave evidently saw no legal alternative to escorting Poppo to Rome and imposing another German bishop on the unsuspecting Roman populace. His treacherous act led to a series of catastrophic events, but I leave his judgment to the Lord. The prospect of a rabid German king bent on destruction of the papacy returning to Italy with his army might have seemed even worse.

Learning that the margrave and his troops had prepared for battle and were approaching the city gates shocked all of us. I informed my brother that I would not tolerate a bloody battle between our men and the margrave's forces. My brother was very upset; yielding without a fight was antithetical to his nature. On the other hand, my pontificate had always been peaceful, and I cherished that legacy. We all hastily retreated to Tusculum and made plans to deal with this usurper on more favorable terms at a future date.

Our wait was short. The German physiognomy has never done well at adjusting to the Italian climate, especially the stifling heat of July and August. Poppo, who was by then using the pontifical name Damasus,[10] soon retreated from Rome to Palestrina,[11] where he perished after a month. Poppo's very brief rule was one of the most depressing periods in my life. Our cause of restoring the unity of the Church had been abandoned by our erstwhile ally and friend, Margrave Boniface, the man most responsible for restoring both my sanity and my pontificate. Furthermore, Italian troops in and around the city lent an air of legitimacy to Henry’s blatantly illegal appointment of the Bishop of Rome.

The monks returned to the piazzas and pulpits, where they vehemently denounced me and my allies as sexual deviants who gained their offices through witchcraft, nepotism, and simony. Some even claimed that I killed the German popes by casting spells from Tusculum The most ridiculous charge was simony. I paid no money for the only office that I ever held, and I never demanded payment from anyone for an appointment.[12] The German bishops, on the other hand, were appointed not by a Church official but by their king, often because of blood ties or loyalty to the crown. Does anyone deem the German method superior?

The people who knew me well understood that the rumors spread by the monks were unfounded. However, even the most outrageous slanders probably found receptive ears as well.

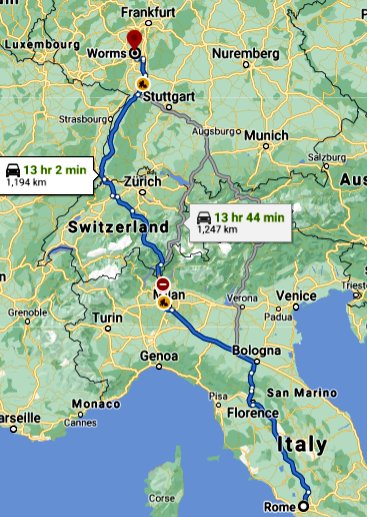

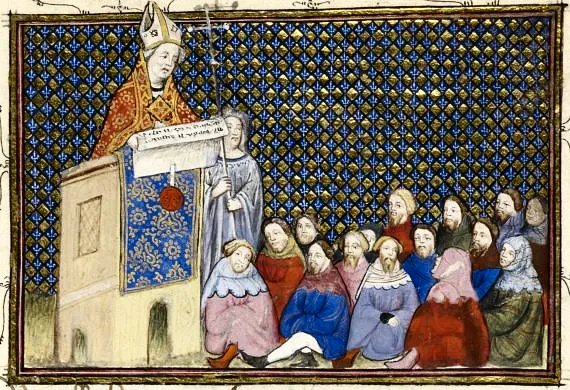

When he learned of Poppo’s demise, Henry announced that before Christmas he would convene an assembly to select the next Bishop of Rome in the German city of Worms[13]. Clerics from papal territories were not expressly barred from this council, but those who made the arduous journey no doubt could expect to view a display of the emperor’s military might and his determination to control the papacy from afar. Henry’s subjects far outnumbered Romans. The emperor had been appointing bishops within his territory since he became king. He had evidently convinced himself that the metallic hat that Bishop Suidger had placed on his head bestowed the authority to choose the Bishop of Rome[14]. It mattered not that that man would thereby also become the Supreme Pontiff of the Christian Church and monarch of the Papal States. I never met the emperor in person, but his actions should rank him as one of the most arrogant men in history. Even now I can scarcely believe that the bearer of the Keys, endowed by Christ himself, had suddenly become the emperor's vassal.

At the news of Poppo's demise I anticipated that my brother and his resourceful allies started to work on a plan to restore my pontificate. I was therefore not surprised to be invited to a meeting with Gregory, the hegumen, and others after the papacy had been vacant for a month or so. I expected that they had worked out the details and were now ready to disclose my role to me. That had always been the order of business.

My brother began the meeting with the glum statement that as long as the margrave’s forces remained in the vicinity, his own troops could not be expected to implement an effective military maneuver to restore my pontificate. Moreover, even if a bloody confrontation succeeded temporarily, the margrave—or someone else—would doubtless be called upon to install the choice of the king’s assemblage in Worms, which most likely would be Henry’s cousin, Bruno, the Bishop of Toul.[15]

When Gregory completed this presentation, no one spoke. I broke the silence with a simple question. “What, then, is the plan?” Another long period of silence ensued.

The hegumen eventually answered in very measured tones. “Your Holiness, we face a difficult situation. A haughty and reckless German king has determined that he knows better than the Romans who should be Bishop of Rome. He has expressed his willingness to use his armed forces as well as the troops of those who have pledged him fealty to impose his will. Another new development is unsettling. The king appears to have reached an accord with meddlesome Benedictine monks. During the period in which your family has restored stability in the Church and throughout the Petrine Patrimony, the Benedictines have tirelessly campaigned for a larger share of power. For years they have enjoyed an alliance with the ambitious but mostly incompetent Crescentii. Now, however, under Hildebrand’s insidious influence, they appear to have allied with the Germans.

“Today those monks continue to preach about the necessity for reforming the Church. They have convinced many in Rome of the righteousness of their cause. Their words are probably even more persuasive outside of the city.

“In short, none of us can envision a plan that under these circumstances could provide a basis for reclaiming the papacy and defending it against our adversaries. It seems foolish to undertake a plan that we all agree is probably doomed to fail.”

Just as Hegumen Bartholomew finished this pronouncement, an unexpected figure limped into the chamber. I recognized my friend Gerard immediately even though his hair, what little still remained on his pate, had for the most part turned grey. He had clearly not shaved in several days. Other areas of hygiene had also been neglected. Nevertheless, I greeted him warmly and embraced him. Out of breath, he collapsed in a chair and apologized for being late.

“The situation is dire,” he reported in the gruff voice that I had not heard for many years. “Several of our closest allies have turned against us. I am no longer certain whom we can still trust. I see no way to prevent the Germans and their allies from installing another foreigner as pontiff. Even if we somehow prevailed in the short term, all signs are that Henry would not hesitate to cross the Alps again, oust whomever we elected, and replace him.”

I was dumbfounded. “Are you saying that if there were a canonical election of the new pontiff conducted by the Roman clergy, they would select another German bishop to rule them? That is a preposterous claim.”

“I am saying that a powerful German emperor has made it clear to everyone, including the Roman clergy, that he will tolerate nothing less. Romans have been wary of war since the times of the Caesars. No one wants a war against the Germans or even against the powerful lords in Italy who owe them allegiance. Romans almost always choose peace over war even if that choice means yielding to outrageous demands of the most bellicose and pig-headed emperor in memory.

“It is now easy for the citizenry to conclude that a change in course is required. The monks have convinced many that the Tusculan pontificates were immoral in the extreme. No one has successfully countered their claims, outlandish as they are.”

“Well, even if you are correct,” I retorted, “we can certainly respond to their attacks on that front. Maybe I can no longer preach in the basilicas, but I still possess the rights of every Roman citizen. We should take our case directly to the people. Let us remind them of the accomplishments of my pontificate as well as the tremendous works of my two predecessors. Who could argue with that? Then we should trumpet the dangers of surrendering control of our lives to belligerent foreigners who are ignorant of our needs.”

My old friend replied, “It is definitely true that we need to ascertain how to garner popular support. We could try what you suggest, but I suspect that in the current climate we would soon be shouted down. The other side is better organized and more experienced at persuasion at the street level. You are still a young man,[16] Your Holiness. We should exercise restraint for the nonce and allow our enemies time to make mistakes. The last two pretenders they placed on the Throne of Peter demonstrated extraordinary incompetence. In addition, after a time the emperor may lose interest in Italy altogether due to exigencies in regions of more strategic importance. Such a change in perspective has happened in the past. In either case our position would be considerably improved by waiting.”

“But what if their mistakes in the interim cannot be undone? Only one year ago everyone assured me that the stakes at that time were so high that immediate action was absolutely necessary. The hegumen insisted then that I was the only man capable of leading the Church through this stormy period. Has that all changed, as well? Is it less stormy now? It does not appear so to me.”

The hegumen fashioned his reply in somber tones. “No. I am more convinced than ever that the Church is in a very serious crisis. I value the contributions that you made as pontiff, and I firmly believe that the best chance for the Church to maintain its strength and unity would be for you to occupy St. Peter’s Throne quickly and permanently. However, based on current available evidence, I cannot envision a plan that promises much hope of achieving that result. As a practical matter, it makes more sense to wait and see if a more propitious situation emerges.”

His words exasperated me. “'A practical matter'? Are we not men of faith? Do we no longer trust in the guidance of the Holy Spirit? Your rhetoric in our meeting in your cell was unquestionably inspired by the Holy Spirit. It kindled in my heart, my mind, and, I think, my soul the desire to fight for a cause that I did not even realize was in jeopardy. I have learned to respect your judgment in every particular, but I cannot understand how you could advise us to cooperate with German interlopers who threaten to undermine our work. If we let this happen, are we not as guilty as they are? Maybe, because we are the ones who comprehend how important the cause is, we shoulder even more responsibility than the barbarians. Every man in this chamber has devoted his adult life to strengthening the bonds between the pontiff in Rome and the rest of Christianity. The Germans, in contrast, consider the Holy See as just another political office that needs to be brought under their control. In their minds the Greeks are territorial rivals, not partners in Christianity. The Benedictines are just as misguided. They recognize that Rome has power, and they want more control over its use. Does anyone here deny any of this?”

No one responded, and so I continued. “Well, I refuse to surrender. I intend to walk into one of the piazzas and explain the situation to whoever will listen. The Roman people know me. The words of others may have turned many against me, but I trust in the Holy Spirit to place the appropriate words in my mouth and to guide me to present them in a manner that will touch the hearts, minds, and souls of the listeners just as the hegumen’s words inspired me. I pledge to do it every day for as long as needed.

“Every day the apostles and martyrs faced more daunting obstacles than a distant German monarch who does not appreciate the limitations of his office. They knew that their cause was righteous and far more important than their own lives and well-being. Against all odds their faith prevailed at the end of those trying times. At no point could they 'envision' how success would come, but they knew that they had to act.

“You, hegumen, convinced me that I was especially chosen for the task of preserving and enhancing the unity of the Church. The German emperor and those accursed Benedictines have no right to disrupt this process. It is the Lord’s work, is it not? How can you, of all people, consider stopping me from fulfilling my destiny just because it did not seem practical?”

A wave of sadness passed over the hegumen’s face as he meekly replied, “You make a strong case, Your Holiness. Please give us a little time to think of a better plan.”

I reluctantly agreed. “One month; no more.”

A month later we met again, and the group pleaded with me not to proceed with my plan to address the public and answer the lies about my pontificate. My friend Gerard and my brother Gregory insisted that this course would in all likelihood only make things easier for our enemies. I chastised both of them for their lack of faith in the power of the Holy Spirit. I chose bitter words that I now regret. I should never have impugned their motives, which were doubtless concerned with my welfare as much as strategy.

The hegumen said nothing. I informed them that I understood and respected their arguments, but my Christian duty led me to proceed with my plan to educate the people of Rome about my family's accomplishments and the evil intentions of the monks and the Germans.

The last thing that my brother said to me that day was this: “This is the final blow, Theophylact. If you persist with this hare-brained scheme of yours in spite of the admonitions of those who have always supported you and who understand the situation best, I wash my hands of you forever. I have rescued you from your idiotic tendencies so many times. I feel quite certain that the rest of these fine people agree with me, but they love you too much to criticize you in your presence.”

Early the next morning I donned my tiara, climbed the Capitoline Hill, and addressed a few dozen citizens who were in the vicinity. For the most part they seemed attentive and respectful. I calmly explained that the Germans had installed short-lived pretenders on St. Peter’s Throne. I explained that the King of Germany and bishops from barbarian lands were at that moment in the process of determining the next bishop for all Romans, not here in Rome but in the heart of Germany. I postulated that I and everyone who was proud to be a Roman citizen found this situation insulting and intolerable. I also decried the monks who fabricated so many ludicrous stories about my pontificate. I forcefully denied their allegations. I swore that I, my family, and our associates had for decades worked tirelessly to promote the Christian Church and the welfare of the Roman people. I also enumerated our efforts to promote the expansion of Christianity, repel the infidels, and to strengthen ties with the eastern patriarchs.

In contrast, I demonstrated that the German pretenders to the Throne of St. Peter, supported by the military might of their liege, King Henry, had seldom been in Rome during the short stints in which they wore the tiara and pallium. They had not even bothered to learn either the ways and customs of the Romans or the requirements of the office of Supreme Pontiff. They spent no time or energy promoting the interests and welfare of the Roman people and the other residents of the Patrimony, and they showed little interest in promoting the spread of Christianity.

German bishops owed their positions to the kings. They were not elected; they were appointed by the king. The German prelates clearly considered acquiring the title of Supreme Pontiff to be just a way to get closer to their real master, Henry, the King of Germany. When they came to the Holy See, both pretenders were already bishops, and neither had even resigned his previous post before taking on the duties of the pontiff. Aside from being contrary to canon law, that was a clear indication that they regarded neither position as a serious responsibility. To them it was just a reward and a part-time job!

I concluded by thanking my listeners for their attention and requested that they discuss with family, friends, and neighbors whether they wished for Germans to run their city, their Church, and the papal territories. This oration was well received, as were the second and third. I noticed, however, that on that last occasion three cowled figures listened attentively on the edge of the crowd. At the end of the speech they huddled together and then hustled off.

Those three speeches instilled in me a warm sense of confidence and accomplishment. I realized that it would be difficult to reach the thousands of people in the city, not to mention the inhabitants of the papal territories, but the Holy Spirit had provided well-crafted arguments. The talks seemed to be having the desired effect on the listeners. The attendance was better and even more enthusiastic on the fourth and fifth days. On the sixth day over one hundred Romans stood in the rain to listen to the Holy Spirit speak through my mouth. It was thrilling.

During the second week, however, the atmosphere changed. Attendance on Monday was even better than in the first week, but men and women scattered throughout the audience occasionally interrupted me to shout rude comments about alleged violations of morality during my pontificate. One denounced me as a sorcerer. At the end of my presentation a Benedictine monk who was accompanied by two women addressed the group. “Fellow Christians, these ladies have intimate knowledge of the goings-on in the papal palaces in which Maledict resided. Please listen to their words.”

The two ladies informed the crowd that they had been handsomely paid by my brother Peter to appear at an assigned date and time at a back door of the Lateran Palace. From there they had allegedly been escorted through dimly lit passageways constructed between the interior walls into a secluded chamber in which they asserted that they had engaged in sexual congress with the pontiff himself. As they spoke they repeatedly pointed at me. One claimed that she had only participated once. The other admitted that she had returned several times because she had no other way of earning money to provide for her children. She said that everyone in Rome knew that the priests had taken all of their money; she was in the small group that knew precisely what they did with it, and she got a little back.

The monk then invited everyone in attendance to join the ladies and himself on a short journey to the Lateran Palace. He said that he would be happy to show everyone the very door through which the ladies had entered and to guide us by torchlight through the hidden corridors to what he called the Den of Sin. He specifically included me in the invitation. “We await your reply, Your Sinfulness. Will you join our tour? My brothers and I have several wagons ready to bear us to the Lateran Palace. We will return everyone here when the tour is completed.”

Shocked and embarrassed, I quickly retreated to Tusculum. I realized that Gerard, Gregory, the hegumen, and the others had been quite correct in their assessment. I never felt that the Holy Spirit had failed me. On the contrary, I could clearly see that my words impressed all who heard them. The fault was entirely mine. I should have been better prepared for the attack, and I showed myself to be a despicable coward when I ran from battle at the first sign of resistance. If I had confidently joined the monk’s proposed tour, the Holy Spirit would have inspired me to find a persuasive way to explain the need for dealing with Satan’s temptations of the flesh even in the heart of Christianity. Perhaps I could have made them appreciate that I was a very young man at that time, and everyone recognizes that young men are subject to extremely strong urges. I violated no commandments; I neither committed adultery nor coveted another man’s wife. My actions were not unnatural or shameful. They were sensible and practical, and I know that they made me a better pontiff. It would have been embarrassing, but I should have been better prepared, and, even when I was presented with a situation for which I was not prepared, I should have placed my trust in the Holy Spirit. In my arrogance and cowardice I had committed the same sin of which I had accused my brothers and my friends.

I failed to follow my own supercilious advice. Instead I retreated to my chambers in Tusculum, and I secluded myself from society. In shame I avoided the public, including my family, friends, and supporters. From others I later learned of Bruno’s triumphant arrival in Rome, arm in arm with the despicable Toad. They both dressed and acted as pilgrims. When he received the tiara, Bruno assumed the name of Leo.[17] The last pontiff who named himself Leo had also been nominated by a German king after the death of my ill-fated relative, Pope John XII.[18]

Bruno spent a few months in Rome. During that time he mandated celibacy for all clergymen, even deacons and subdeacons. Why he considered their sexual abstinence so important was never clear to me. Jesus never made such demands on his apostles. We know that Peter, the apostle who was given the Keys to the Kingdom, was married and had children.

Bruno also inveighed against simony. I have always held that no benefice should be auctioned to the highest bidder. I had never bought or sold one, but I suspected that in some regions over which I exercised no control and little influence the exchange of money for clerical offices was common. However, it seems absurd that Bruno, a man who had been appointed to his high office by his cousin, would feel free to criticize others who lacked his innate advantages. My enemies ranted about the need for reform, but no one ever seemed to mention reforming the king’s ability to invest bishops at his whim.[19]

Bruno immediately called a synod in Rome. He invited me and a few associates to attend. Aware of the mistake in judgment that caused John Gratian to exchange his pontificate for lifelong imprisonment in Germany, we had no intention of subjecting ourselves to the humiliation that my godfather had encountered in Sutri. We did not respond .

Bruno was incensed. In an act of unmitigated vengeance the newly crowned Vicar of Christ sent his forces to lay waste to the fields and vineyards adjoining Tusculum in order to starve my family and neighbors to death. My brothers, however, anticipated this tactic and had stocked sufficient stores to withstand a siege. Our people suffered needlessly because of this heinous act, but Tusculum survived the vendetta.

Like all of the other Bishops of Rome appointed by King Henry, Bruno soon felt restless. He loved to travel around Henry's lands lecturing about how the clergy should behave in their public and private lives. Because he had the backing of the German king, Christians in those regions reportedly felt obliged to pay him respect.

After a few years, however, the truculent side of Bruno’s nature again became dominant. He grew intensely distrustful of the Normans, who, having converted to Christianity decades earlier, established themselves as rulers of much of southern Italy. Bruno was determined to eliminate them entirely. He beseeched King Henry for assistance in this quest, but none was provided. Likewise, Bruno convinced only a few Italians to risk their lives fighting fellow Christians who were renowned for their military prowess. In the end he resorted to hiring a band of blood-thirsty Swabian[20] mercenaries. He foolishly led his ragtag army into Norman territory in Apulia. The Normans were very reluctant to engage in combat against their fellow Christians, but the Swabians eventually provoked them into battle at Civitate.[21] The Normans crushed the papal forces, and held Bruno captive in Benevento until just before his death.

Composing the next few sentences causes me great anguish. I must, however, continue, for Bruno’s actions had such a dramatic effect on all Christianity that passing over them would be irresponsible.

From his prison cell Bruno, acting on behalf of the Roman Patriarchate, made a rash decision to dispatch a delegation to Constantinople to demand that the Greeks acknowledge the primacy of the Bishop of Rome. How could a man in his position—unable to return to the Holy See—muster the temerity to issue an ultimatum of this nature? I never met Bruno, and so I cannot speak with authority on any aspect of his personality, but his actions make him seem both arrogant and foolish. Perhaps someone else actually made some decisions for him. The only man of my direct acquaintance who possessed so much arrogance and foolishness was Bruno's close associate and administrator, the loathsome Toad.

The man chosen to lead the delegation to Constantinople was Bruno’s longtime friend, a French monk named Humbert. A few years earlier Bruno had elevated Humbert to the rank of Cardinal-Bishop of Silva Candida, an act that clearly displayed the pretender’s ignorance of the primary responsibility of cardinals, which was to serve as a link between the pontiff and the faithful in the suburbicarian dioceses.[22] This monk reportedly had attained a modicum of familiarity with the Greek language, but his tactics revealed little comprehension of the complex history of transactions and communications between Rome and Constantinople. Humbert came armed with a set of laughably bogus documents[23] that portrayed a relationship between Emperor Constantine and Pope Sylvester I[24] that every scholar in Constantinople and, for that matter, Grottaferrata, knew was impossible. Humbert also brought a decree excommunicating the Patriarch of Constantinople. He left this outrageous document, which had been signed by Bruno, on the high altar of the Hagia Sophia just before returning to Rome.[25] Thus, in the course of a few short years all the progress that my family had effected toward a strong and unified Church was undermined by the ignorance and stubbornness of these self-righteous transalpine zealots.

This fact must be recognized by all. Bruno’s six years as pretender to the Supreme Pontiff were an unmitigated disaster for Christianity. He wandered around France and Germany for years preaching the rhetoric of reform without attending to the problems of Rome, the Petrine Patrimony, or the Church. He started a bloody war with fellow Christians that accomplished nothing and depleted the treasury. It caused the deaths and injuries of many faithful Christians and his own imprisonment. From prison he dispatched his arrogant and ignorant cronies to Constantinople, where they insulted the eastern Church and excommunicated its leader, thereby for the first time in its thousand-year history Christianity was split into two independent entities.

As unspeakable as all these disasters were, none was the worst result of his reign. For in this period the ignominious Toad managed to slither his way to the top of the clerical establishment. He came to be viewed by both the Benedictines and the Germans as a respected figure. In fact, he was called on to manage the affairs of the Papal States during Bruno’s tours, his ill-fated invasion of Apulia, and his imprisonment. Reputable sources claimed that Humbert’s mission to Constantinople was actually the Toad’s brainchild.

Some of Bruno’s associates have written that he was a saintly man[26] and a great pope. His intentions may have been good. I cannot judge his mental state, and the Lord specifically prohibits all men from engaging in such judgments. Nevertheless, I hereby assert that in the millennial history of the papacy no pontiff living or dead has wreaked such havoc. No honest man can deny this fact.

Despite the disasters that befell all three Germans who had reigned as Supreme Pontiff, the Toad nevertheless used the occasion of Bruno’s death to journey north to Germany again. There he beseeched King Henry to appoint still another of his entitled friends as Supreme Pontiff. As a result, Gebhard, the Bishop of Ratisbon,[27] came to Rome and was given the papal tiara under the name of Victor.[28] For two years he paraded around Europe displaying his new hat. He spent little time in Rome. In fact, Gebhard was at Henry’s side when the emperor died.[29] Gebhard was even named guardian of Henry’s infant son, another Henry. Along with Henry’s widow Agnes, the pontifical pretender served as regent of Germany and much of Italy for a year or so until something impelled him to return to Rome. He died in Arezzo before reaching the capital. Gebhard had spent so little time in Rome that he probably would need to hire a guide to find the Lateran or St. Peter’s.

The Toad was evidently prepared for Gebhard’s death. Within a few days he had engineered the election of Frederick of Lorraine, whom Gebhard had appointed Cardinal Priest of San Crisogono. When he assumed the role of Supreme Pontiff he took the name Stephen.[30]

Frederick’s principal qualification was his blood. His brother was Godfrey of Lorraine, who, by his marriage to Margrave Boniface’s widow, Beatrice, was by far the most powerful man in Italy. Frederick was therefore the first pontiff in decades who could feel relatively secure that the Petrine Patrimony would not be subject to military incursions. As pontiff he took advantage of the situation not to extend or solidify Christianity but to prepare for a resumption of Bruno’s idiotic war against Norman Christians. Fortunately, the Lord terminated his pontificate and his life before he could implement his plans.

At Frederick’s death five different foreigners had played the role of Supreme Pontiff. I ruled the Church unopposed for considerably longer than the five of them combined. What a contrast can be drawn between their pontificates and mine! Anyone alive at the time will testify that the hallmarks of my pontificate were peace, tranquility, spreading of the faith to distant realms, and cooperation with our fellow Christians in all quarters. By contrast, the Germans and their monastic supporters led by that misbegotten monster, the Toad, had subverted every constructive effort that I and my associates had undertaken. This string of barbarians had left Rome, the Petrine Patrimony, and, in fact, all Christianity in ruins. Perhaps the most incredible fact is that each usurper had deliberately abandoned Rome and died outside of the Holy See.[31]

The Roman people and their clergy had evidently finally had enough of the Germans and monks. For me one of the saddest aspects of this situation was the fact that Hegumen Bartholomew, who had died while Gebhard wore the tiara and the pallium, did not survive to see the Romans regain control of the papacy. Perhaps Saint Bartholomew, as I thought of him then and now, could help the rest of us obtain divine assistance in our quest to reestablish a unified Christian Church. I often prayed for his guidance, and so did many others.

[1] Probably 1046.

[2] Sutri is about thirty miles north-northeast of Rome.

[3] It is indeed puzzling why Pope Sylvester III was ever placed on the official list, but his name is still there in 2019.

[4] For centuries the nobles and clergy disputed over the authority to appoint bishops and other members of the religious hierarchy. This dispute is commonly called the Investiture Controversy or Investiture Contest.

[5] Bamberg is in central Germany.

[6] In the Middle Ages no bishop could become the bishop of another see. In the ninth century the bishop who became Pope Formosus was excommunicated for even entertaining the idea of becoming bishop of a different diocese. Theophylact and his uncles were never bishops of other dioceses.

[7] Pope Clement II was elected on Christmas Day, 1046. He died on October 9, 1047.

[8] This clearly refers to the Byzantine Emperor and the Patriarch of Constantinople.

[9] Brixen is in the semi-autonomous Trentino-Alto Adige (also known as Südtirol) region of present-day Italy. The area was part of Austria prior to the end of World War I. Even today many residents speak German, not Italian.

[10] The pontificate of Damasus II only lasted from July 17, 1048, until August 9.

[11] About twenty-two miles east of Rome.

[12] The author never addressed how the “negotiations” with John Gratian’s representative differed from simony. He also did not mention whether money was paid by others.

[13] Worms is 571 miles north of Rome, a journey of several weeks in the eleventh century.

[14] Pope Clement II also named Henry Patrician of Rome and gave him the diadem of that ancient office, which some claim provided that authority.

[15] Toul is in the eastern part of present-day France. It was annexed to France in 1552. Prior to that it was part of the empire ruled by Germans. Eleventh-century Italians would probably consider its residents Germans.

[16] If the chronology of chapter 1 is correct, he would be about thirty-six years old at this time. The list of younger popes is very short.

[17] Pope Leo IX’s pontificate lasted from February 12, 1049 until April 19, 1054.

[18] Pope Leo VIII, a Roman, was appointed pontiff by Emperor Otto I in 963.

[19] This claim was true at the time, but the reformers later added removal of the rite of investiture by kings and nobles to their list of priorities.

[20] Swabia is a region in southwestern Germany.

[21] June 18, 1053.

[22] The first cardinals were appointed in the sixth century. They served as liaisons between the pontiff and the areas just outside of Rome. The German popes began awarding cardinal-bishoprics to several transalpine clerics.

[23] The author is probably referring to the text now called “The Donation of Constantine,” which subsequently was shown to be an eighth-century forgery. This text claimed that Sylvester had cured Constantine of leprosy, converted him, and baptized him. In gratitude the emperor bequeathed most of Western Europe on the papacy. Reliable accounts state that Constantine never was a leper and refused baptism until he was on his deathbed.

[24] Pope Sylvester I reigned from 314 to 335.

[25] This act was the proximate cause of the Great Schism, which has never been resolved.

[26] In fact, Pope Leo IX is indeed a saint in the Roman Church. He was canonized in 1082 by none other than Pope Gregory VII, the man referred to as Hildebrand (and the Toad) in this document.

[27] Ratisbon, now generally called Regensberg, is in Bavaria.

[28] Pope Victor II reigned from April 13, 1055, until July 18, 1057.

[29] October 5, 1056.

[30] The pontificate of Stephen IX began on August 3, 1057, and ended on March 29, 1058.

[31] Actually, Pope Leo IX, as the author himself indicated earlier, returned to Rome just before he died.