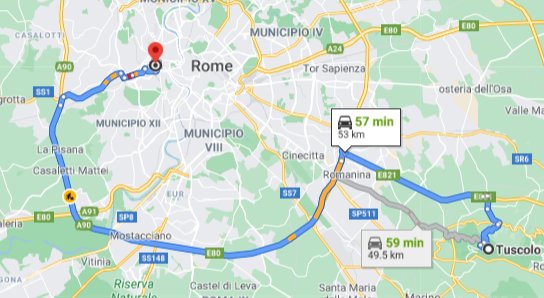

During the years of exile from my rightful office of Supreme Pontiff of the Christian Church I resided in a modest house in Tusculum located within a quarter mile of the cathedral. My majordomo Paschal managed the affairs of my house, and his two assistants attended to my minimal needs.

While Maltempo was still healthy, I was as thrilled as ever to mount his broad back for rides throughout the beautiful Alban Hills. As he grew older it would have been cruel to force such activities on him. I continued to visit him daily, and I brought him treats and showered him with affection until the end. At his death I felt as if a piece of my soul had withered into a chunk of charcoal, dark and burdensome. His demise was not as devastating to my spirit as when I lost Tigra or when I learned of my mother's death, but it did crush what little remained of my spirit. I sat by myself under a tree in the woods and wept for a long time.

During the hegumen's lifetime I actively communicated with him. Every month or so I sent to him messages[1] in which I outlined my thoughts about reclaiming St. Peter’s Throne. His replies were uniformly thoughtful and gracious, but he clearly stated that he no longer believed that Romans would tolerate me as their bishop again. Although I often reckoned that I had brilliantly refuted his arguments in each particular, I never convinced him. The interchange was uniquely pleasurable to me in the sense that it challenged my mental faculties. It was also frustrating, and it occupied a considerable amount of my time over the years. The hegumen’s death left another gaping hole in my soul. During my exile he was my primary contact with the world in which I had willy-nilly resided for so long. Nearly everything that I learned about historical events in the years after I was forced out of Rome I gleaned from my correspondences with the hegumen. After he died, I lost interest in Church politics. It was never a focus of my life anyway. I seldom interacted with my brothers or their families, and I never encountered any other associates.

The Bishop of Tusculum, a distant cousin, was born a year before I was. We had been friends when we were young. He knew that I was a very early riser, and so he let me celebrate the first Mass at the family's chapel in the cathedral every morning. For the first few years of my exile the attendance remained rather steady, perhaps thirty or so worshipers. Some probably came just to see a former pope who had become a pariah. Some may have attended from habit developed over the course of their lifetimes. As the years went by the numbers declined. By the pontificates of Gebhard and Frederick, attendance could be counted at a glance.

After Mass I usually took a stroll. Sometimes I wandered around Tusculum, but usually I explored nearby fields and forests. The streams seemed to have a soothing effect on my battered spirit. Occasionally I sat beside one and contemplated the water for hours, fascinated with the progress of a waterborne twig here or a frog there. I learned to imitate the calls of various birds, and I occasionally engaged in extended conversations with winged companions. I often became so engrossed in these activities that I forgot where I was and how I had arrived there. Fortunately, Tusculum lies atop a tall hill, and as soon as its walls[2] came into view I reoriented myself well enough to return home.

One day I noticed that only one person was present at Mass, a woman. She had been wearing a hood and a veil throughout the ceremony, and so I could not recognize her. When I presented the communion host to her, I saw a rather aged version of Costanza’s face. My startled fingers released their grip on the paten, and a dozen consecrated hosts tumbled to the floor. I instinctively dropped to my hands and knees to collect them. After I had retrieved them all and placed them back on the paten, I had great difficulty regaining my feet without spilling the hosts again. The situation was extremely embarrassing. I crawled on one hand and two knees to a nearby chair in order to effect a recovery to a standing position.

After Mass I changed from the vestments into my usual clothes and hastened home. Despite my efforts, however, Costanza waylaid me before I reached my destination. “Your Holiness,” she said, “please stop for a moment. I need to speak with you.”

I stopped and tilted my head to one side. I intended for some words to accompany this gesture, but they stubbornly remained stuck in my craw. “Merciful heavens,”[3] she said, “Look at you. How can you do anything with those claws?”

I gazed at my hands and discovered that my fingernails had grown quite long. In fact, they were shockingly long. I could concoct no sensible explanation of how this had escaped my notice. I therefore remained sheepishly silent.

Costanza then held my chin in her hand so that she could look at my eyes. Maintaining her grip, she then tilted my head this way and that. “How did you let yourself deteriorate so? Have you been sleeping at all? Do you eat regularly?”

She did not await the answers that I was struggling to form. Not needing to interact much with humanity for several years, I had lost the knack entirely. She grasped me by the hand and led me to my house as a mother might lead a disobedient child struggling to avoid punishment for mischievous deeds. When we reached my house she summoned Paschal. The other servants had the good sense to vanish.

“How,” she challenged the startled majordomo, “could you allow him to appear in public looking like this? Have you forgotten who is entrusted to your care? For many years he was the Supreme Pontiff of the entire Church, the Vicar of St. Peter. Those were proud days for us when kings and emperors prostrated themselves before him. He was a great man, and if not for cruel fates he would hold that position today. He deserves respect and, above all, good treatment. Your only assignment has been to care for him, and you are evidently doing it very poorly. You have no other responsibilities; how difficult can this assignment be?

“Now listen closely to me. Accompany him to his chambers and help him clean up. Then summon me so that I can try to improve his appearance a little. Meanwhile, your primary task is to obtain some suitable garments for him to wear. I know for a fact that you are given a substantial allowance for that expressed purpose. I am the one who keeps the accounts for those funds. Did you know that? What have you been using this stipend for?”

Paschal stammered an incoherent reply. Fortunately for him Costanza was in too much of a hurry to conduct an impromptu audit. When she had finished berating him, he drew me a bath and brought me everything that I needed to cleanse myself. He then inspected me and found that I was still substandard in a few areas. I must have neglected this aspect of life for some time. I came to realize that my disgusting appearance had been disgracing my friends and my family, and I was completely unaware that I was even doing anything wrong. Nobody mentioned it. On the other hand, almost no one ever talked to me about anything.

A little later Costanza joined us. She trimmed my fingernails and my hair and shaved my beard. When satisfied with her work, she asked if I planned to attend the investiture looking so disheveled. I remembered investiture ceremonies, but no one had told me that one was imminent. In any event, I doubted that I would be welcome at any such event. I could think of nothing to say.

She looked at me deeply again. Her gaze was equal parts pity and sadness. My impulse—and it was very strong—was to run away and hide from her penetrating eyes. Perhaps she sensed that I was about to bolt. She grabbed me by my shoulders and spoke in unyielding tones. “Tomorrow, Theophylact, is perhaps the most important day in our lives. Come to the family palace at dawn. The whole family is riding down to the Vatican together, and you must attend.”

“The Vatican?” I asked. “Why are you going to the Vatican?”

“Tomorrow is the day that the tiara will be placed on the new pontiff's head. It will be a great day for Rome and for our family.”

“Has Pope Victor died?”

She paused again in shock at my ignorance. “Well, yes, he did, about a year ago. Last week his successor, who went by the name of Stephen, also succumbed to an illness in Florence. A new pope has been elected, and the Roman people are excited about the fact that he is one of their own, and the Germans and their perfidious allies had no say in his election.”

“But I am still the real pontiff. If the usurpers have at last been ousted, I should resume my pontificate.”

She brought her hands together in front of her face as she mentally composed her reply. “In a just world you would probably be right. I hope and pray that we can find such justice in the next world. No one promised that anything resembling fairness would reign here, and I have seen no sign that it might occur any time soon. “Tomorrow, however, the next best thing will happen, and your heart should be bursting with joy.”

To what could she be referring? I could not even imagine. She continued, “One of your relatives, the Cardinal-Bishop of Velletri, has been elected as the new pontiff. The ceremony takes place tomorrow. The return to righteousness in Rome will be an exceptionally difficult journey for all of us, but this event shows great promise as the first step back on the path that your family and friends worked so hard to clear. I will not take 'No' for an answer. I insist that you be at the palace when the family departs for the Vatican. If you are not there, I swear that I will come and retrieve you. If you hide, I will find you. I know you, Theophylact.”

I tried to remember which of my many cousins might be Bishop of Velletri, but no plausible candidate came to mind. I remembered Leo,[4] of course, but I was pretty certain that he had died.

I promised to be at the palace in time for the departure. Shortly after Costanza departed Paschal returned with new clothes for me. When I compared them with what I had been wearing, I was shocked to see how dirty and threadbare the old ones were. I tried without success to recall when I had last asked Paschal to obtain new raiment for me. The hegumen was probably still alive when last I considered my wardrobe. Maltempo might have still been trotting across the fields. In fact, I might have still been on St. Peter’s Throne. It astounds me that many of my childhood memories are much more vivid than my recollections of the period of my exile. My only really vivid recollections from those times are observations of unusual behavior by animals.

I also tried to recall the last time that I had seen my brothers or Cardinal-Bishop Peter or Gerard in any of his guises. It had been months or even years earlier. I could recall no specific occasion since my ill-starred decision to orate in the piazzas. How many years earlier was that? I had no idea. It could have been five; it could have been twenty. As the critical elements of my life had died or were snatched away, I failed to replace them with anything meaningful. Piece by piece I had allowed my life to disintegrate. I could not summon sufficient energy to change it, and I lacked the willpower and courage to end it.

Sleep eluded me the night before the investiture. Bits and pieces of my life in Rome popped into my memory. Embarrassing mishaps replayed in my mind, particularly the cowardly conclusion to my last public appearance. I longed to spend the day with my friends who lived in the forest and streams. They did not seem to care that I was shunned by humans. I realized, however, that I must keep my word to Costanza if only because I knew that she would seek me out, and that would be worse.

With trepidation I set out for the family’s palace in the dark, timing my arrival there for shortly before sunrise. To my surprise, I was greeted warmly by my brothers and their wives. Even Gregory, who walked with a pronounced limp, came over and gave me a hug. “By Bacchus’s wine-soaked beard!” he exclaimed. “What has become of you, Theophylact? You are scarcely more than a skeleton. And what happened to your teeth?”

His remark about my teeth surprised me. I moved my tongue around in my mouth and determined that quite a few seemed to be absent. I had only a vague recollection of losing one or two over the years. When had the rest disappeared, and what was the cause? I tacitly resolved to keep my mouth closed in shame as much as I could.

In the basilica I found myself positioned between the wives of my other brothers, Peter and Octavian. I knew neither of these ladies very well. On the last occasion that I had seen Octavian he was not even married. I learned during the ride down to Rome that he and his wife had two children, and neither could be mistaken for an infant.

I was quite familiar with most ceremonies involved in a papal investiture. Someone pointed out the new pontiff to me, but I did not recognize him. He was rather tall and thin. He could not have been more than thirty years of age. His career must have been remarkable for him to vault past so many other prominent clerics, including the Toad himself, to be elected Supreme Pontiff of all Christendom. I felt a strong desire to know him better, but I realized that he undoubtedly had far more important things to do than to talk with me. It occurred to me that I could not cite even one person other than the Toad who was involved in running the Church. I could not guess which attendees were the new pontiff’s friends and allies, or, for that matter, his enemies.

During the ceremony I gazed around the basilica to see how many people I recognized. I expected the Toad to be present, but I did not spot him. He must have been absent; if there, he would have taken every measure to assure that everyone acknowledged his presence. I thought that I recognized a few clergymen, but they all seemed so old that I may have been mistaken. Since the emperor's cronies had been in charge of the Holy See for years, I expected to see a number of Germans. However, if any were there, none stood out from the rest of the crowd. No one approached me, and I stayed with my family and tried to avoid attention.

My first great surprise was the young man’s response when he was asked by the cardinal-bishop[5] serving as camerlengo what name he chose to use as Supreme Pontiff of the Christian Church. He answered with an unwavering voice, “Benedictus”. A chill ran through me, and a grin appeared unbidden on my countenance. When I remembered the condition of my teeth, I shut my mouth and lowered my head in embarrassment.

Pope Benedict X then received the most prominent symbols of his new office, the pontifical pallium and the tiara. At the end of the ceremonies, everyone lined up for blessings. The new pontiff bestowed individual blessings on each attendee. As family members, my brothers and their wives and offspring took a position near the beginning of the line. Each person in turn prostrated himself before the pontiff, kissed the cross on his slipper, and then accepted his blessing. When I appeared, however, the young pontiff’s eyes widened, and he steadfastly refused to allow me to perform the act of obeisance. Instead he addressed me as “Your Holiness.” He asked me to bless him, and I did. He then bestowed his blessing on me. It was a poignant moment for both of us.

A procession through the city followed the blessings. My entire family was near the front of the triumphal march. After so many years of foreign domination, the citizens were ecstatic at the sight of one of their own once again wearing the pontifical tiara. At one point Costanza slyly maneuvered over to walk by my side. She asked me surreptitiously what I thought of the new pontiff. I told her nonchalantly that he seemed like a nice young man, and he would certainly make a welcome change from the Germans who preceded him.

“Do you recognize him?” she asked.

I asked her if I had met him before. She replied that she doubted it and asked me if he looked familiar. I tried to think of all my relatives in Tusculum and the region. He did not really resemble any of them. He certainly did not look like any of my brothers. I responded to Costanza that he did not look familiar to me.

“Theophylact,” she finally disclosed, “the new pontiff is our son.”[6]

She then ambled cheerily back to her husband’s side as if we had been discussing what to eat. Her pronouncement dumbfounded me. At my next opportunity to examine the young man I noticed that he had curly reddish hair that was somewhat reminiscent of Costanza’s. In other respects he did not resemble her much. I tried to construct a mental image of myself at his age, but it was difficult. While I was engaged in this speculation the pontiff turned toward the crowd and raised his right hand to bless the public. His hands were large and bony. I glanced down at my own. If they had not been so emaciated and wrinkled by age and neglect, they would surely have been a close match for his.

The conclusion of my story approaches. It is commonly known that the ending is not pleasant. The Toad and his monkish friends regrouped and after a few peaceful months managed to drive Pope Benedict X from Rome. Eventually he was forced to hole up in Count Gerard’s castle. Christians slaughtered Christians in the senseless bloodbath that ensued. The monks obtained military support from the indomitable Normans, of all people, and eventually prevailed. The Toad himself led this bloodthirsty assault, the goal of which was to kill the pontiff and all supporters. My son was lucky to escape with his life.

The insurgents placed on the Throne of St. Peter another man from beyond the Alps. This one, Gerard of Burgundy,[7] had previously been installed as the Bishop of Florence. The new usurper almost immediately established a new set of rules of papal succession by which only cardinals would be allowed to vote in pontifical elections. Most cardinals whom my uncles and I had appointed were by this time deceased. The majority of the cardinals when Gerard took office owed allegiance to the Benedictines or the German monarchy. Very few were Romans.

Think of it: Romans officially no longer had any say in the selection of their own bishop! Instead, foreigners, most of whom were appointed by Germans, would henceforward choose the Bishop of Rome. Some Romans might even have considered this a sort of progress since at least naming the pontiff was no longer a right of whoever was powerful enough to call himself King of the Germans.

The last episode of my story has never been disclosed publicly and is known to few people indeed. It remains extremely vivid in my memory. I can envision the scenes and hear the dialogue clearly, but the recollections are so disturbing that I must wonder how much credence they deserve. No witnesses were present at the critical moments. I will recount everything in as much detail as I can recall.

It began when I heard a knocking on the front door of my house. Prior to that day no one had visited me in months. Paschal responded to the summons and informed me that a very old monk wanted to see me. I walked to the door, and there beheld my old tutor, Brother Clement. His posture was no longer erect, and his face was drawn and corrugated. He supported himself with a cane. Nevertheless, I would have recognized him anywhere.

“Your Holiness,” he began, “can you spare me a moment? Do you remember me? I am Brother Clement from Grottaferrata. We spent a good deal of time together many years ago.”

I had no trouble responding to him. “Of course I remember you. I have nothing but fond memories of your lessons. You could not possibly realize how much I treasure that period. If you demand the rest of my hours on this earth, I will gladly give them to you.”

“Thank you. I appreciate your generosity. I have come to ask a rather large favor. Can you return with me to the monastery? A man who recently arrived there is disabled and in great pain. His injuries are so severe that we fear for his life. He has asked that you hear his confession and administer to him the last rites.”

This request seemed very peculiar. Any priest at the monastery could provide these sacraments. I could not imagine why my presence would be required or requested. Brother Clement must have seen the puzzled look on my face. He said, “The injured man is your friend from Archbishop Lawrence’s class, Gerard.”

I made a few arrangements and then accompanied him back to Grottaferrata. We arrived shortly before the evening meal. I asked the monks to show me to Gerard’s chamber, and I entered by myself. I beheld my best friend lying on the bed in obvious agony. His hair was almost all gone, and the strands that remained were white, as was his beard. One of his ears was missing, and a bandage covered one eye. His face was bathed with perspiration. Brother Clement explained that one of his legs was gangrenous, and his back had been broken. Gerard was awake, but he lay at a very peculiar angle. A chair was placed beside his bed so that he could view its occupant without moving his head. I sat down in it.

“Greetings, Theophylact. Thank you for coming.” His words were uttered in the gruff voice that I remembered, but they were breathless, as if a supreme effort was required to produce each syllable. “Please try to remain as still as possible. Any small motion, whether deliberate or reactive, can cause me excruciating pain.”

I softly promised to remain as motionless as possible. I felt confident of my ability to do nothing, a talent that I had been developing for years.

He continued. “I brought you a present. It is in the rucksack in the corner. You will find the gift wrapped in a blue-stained cloth. Could you retrieve it now? Be very careful with it, and do not unwrap it.”

I did as he specified. The object was less than two spans long and no more than three fingers wide. As I sat back down I informed him that if I was to hear his confession and provide absolution and the last rites, then I would need someone to fetch materials for those sacraments. He said that he did desire for me to hear his confession, but not as a priest or as the pontiff, only as a lifelong friend. He insisted that he wanted my attention and understanding, not my absolution. He freely admitted that in his lifetime he had committed numerous mortal sins, and he seriously doubted that he would be able to remember more than a small sampling. Since he was not even slightly remorseful about most of them, he was sure that no priest would grant him absolution. He did not want to put me in the awkward position of being forced to deny him absolution and thereby condemn him to eternal damnation and suffering.

He insisted that he had long ago recognized that religious rituals were all a sham. If hell existed, which he professed to doubt, he was prepared to spend eternity there. At least he would be among friends and the like-minded. If he somehow ended up in paradise, the only person he would know there would be Hegumen Bartholomew, and he had no desire to face the saintly monk’s inevitable interrogation. “If he had known what I was doing,” Gerard insisted, “he would have done everything in his power to stop me decades ago.”

Gerard then informed me that when he was an adolescent, even before he had enrolled in Fr. Lawrence’s class, the hegumen had taken him into his confidence. The monk described how the founder of the monastery in Grottaferrata, Nilus, had several years after his own death appeared to Hegumen Bartholomew. The hegumen claimed that this event had occurred in broad daylight, and he was certain that it was neither a dream nor a hallucination. According to Bartholomew, Nilus described the details of the plan that Nilus and my own grandfather, Count Gregory, had hatched in order to rescue the Church from the clutches of the Crescentii and other nefarious influences. Nilus insisted that the plan had been divinely inspired. Count Gregory’s entire family was involved in the details of the project, which evolved somewhat over the years to adapt to unforeseen circumstances. Gerard stated that from the beginning my own role was the most crucial one because during my adult years would arise the greatest threats to the strength and integrity of Christ’s Church on earth. According to Hegumen Bartholomew, I alone possessed the set of skills as well as the personality needed to overcome these problems. Count Gregory’s son Alberic, my father, had arranged for me to receive the education necessary to make the most of my talents. Hegumen Bartholomew assigned Gerard the role of keeping me on my predetermined path by providing advice and protection at critical times.

At that point Gerard closed his eyes for a few moments, shifted his weight slightly, and gathered his strength. The hegumen was only a few years older than Gerard, but to the young man he seemed extremely wise. Bartholomew understood how to portray this quest so that participating in it excited a young man like Gerard. The hegumen told him that just as I was a special person uniquely qualified for my part in the divine plan, so also was he, Gerard, specially chosen to ensure that I was able to employ my special gifts. Gerard was so eager to help that it became his life’s work.

Gerard declared that most of his life had been devoted to the thankless task of protecting me so that I could fulfill my mission. I already knew about some of the sins that he had committed in my presence, but his life outside of my view was, he claimed, much more scandalous. While he was awaiting my arrival at the monastery, he had pondered whether there was even one sin that he had never committed. The only one that came to his mind was sodomy, and that was only because no situation had arisen in which it was needed. “As disgusting as I find the idea, I would have had no qualms about engaging in it if the situation required it. I was that devoted to my duty.

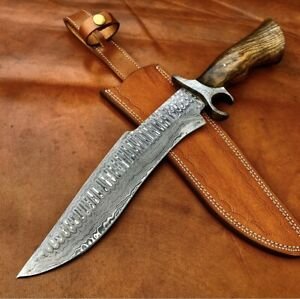

“Theophylact,” he continued in a quiet tone, “I have even murdered people, including five pretenders to St. Peter's Throne as well as numerous others just so that I could gain access to the usurpers. Several of these crimes were committed with the instrument that lies in your lap. Unwrap it, please, but handle it carefully. Under no circumstances touch the blade.”

In the cloth lay a small but sturdy dagger in a thick leather sheath. I clumsily dropped it on the floor. Gerard calmly asked me to pick it up. He also firmly warned me to keep the blade within the sheath. He alleged that the blade was coated with a poison that would, without fail, kill a man in an hour.

“I need you to use that blade on me, Theophylact. The monks here will be happy to pray for me for months on end, but they would never agree to provide the assistance that I need to put an end to my agony. They fantasize that my pain may induce me to renounce my sins and thereby gain salvation. I believed in what I was doing then, and I still do. I have no remorse whatever. I failed, your brother failed, the hegumen failed, and you failed, but what we attempted was at all times in the best interest of all Christians. I believe in very little, but I still believe in that.

“Will you do what I ask? Very little force is required. The blade is extremely sharp. Just prick me anywhere on exposed skin. Then just depart. No one will suspect a thing. I have never asked anything of you before, but you are the only person who can grant me this boon.”

I sat there looking at the instrument of death lying on my lap. No words came to mind. I knew perfectly well that I could never cause the death of anyone, let alone my best friend, a man who had dedicated the greatest part of his life to protecting mine. I did not know what to say. No words seemed adequate.

Gerard’s tone was still muted, but it was calibrated to penetrate my very soul. “You owe me this, Theophylact. After you landed yourself in that mess with Costanza, I protected you. You know that you would never have survived that journey without me. Over the years I have willingly risked my life again and again so that you could fulfill your destiny. I did so gladly. I even recruited the most wonderful woman that I have ever met, the one you know as the baroness, to the cause. She has already given her life, and probably her immortal soul, for you. Her demise caused me nearly as much pain as I am feeling at this moment.”

I was shocked to learn of Ingetrude’s death, but I dared not interrupt his narration.

“I saved your son’s life, too. Those maniacal Normans had cornered him in Saxo. Hildebrand’s hounds were baying. I played the last card remaining in my deck. It left me as you see me now, but it covered his escape.”[8]

A cry of agony escaped his lips. Evidently his forceful delivery of this declaration inadvertently caused him to move a little. I was equally shocked by the scream and the fact that Gerard evidently already was aware that Pope Benedict X was my son. When I asked him how he had come to his conclusion concerning the young man's parentage, he merely replied with a grunt that his vision was still functioning.

Once again he stopped to summon up a little energy. “Despite all of the time that we have spent together over the years, Theophylact, you have never done anything for me. Nothing! In my entire life I never asked for even one favor from you. If you believe in justice, in basic fairness, or in mercy (as all Christians claim to do) you will do as I ask. In our relationship all of the expenses are on my side, and the income is all on your side. I demand a reckoning!”

The weapon fascinated me. I turned it over and over in my hands and examined it a little more closely. The handle was plain wood, and the sheath was unadorned leather. Nothing about it appeared exceptional. It was like its owner—nondescript in appearance but complex and deadly in action.

My mind could assemble no words that would assuage my friend’s pain. I could not possibly condone the actions he described, but neither did I condemn him outright. The whole situation struck my heart as unbearably sad. Tears began to flow down my face.

Bitter scorn permeated his voice. “I have no use for your sympathy. It repulses me. For the first time ever I am asking you for action. Be a man. Be a friend.” His voice rose a bit. He probably was trying to shout, but he lacked the vocal strength. “Put me out of this pain. NOW! I am no longer asking; I demand it.”

I sobbed and told him simply, “You know that I would never do what you request. It goes against my nature, my training and education, and my upbringing. If you were my worst enemy, I would refuse. If my life were at stake, I would not do it. I know the work of Satan when I see it. There is nothing more to say.”

His retort was biting. “No, there is one more thing. I should have eliminated Hildebrand before he discovered how dangerous I was. However, he was never the biggest threat to the successful execution of the plan. You were, Theophylact. The hegumen accurately evaluated your abilities, but he failed to account for the unpredictable side of your nature. While Count Alberic was alive, he was able to …”

“My father never …”

“Your father? Do you believe that you are related to a man of such iron will as Count Alberic? Why? You have absolutely nothing in common with him. You look nothing like him, and your talents and abilities do not overlap his in the slightest. The idea that you might be related to him is preposterous. Such a lion could never sire a butterfly like you.”

Mute, I sat there staring at him, trying to digest what Gerard was telling me. He seemed content to have quieted me and resumed his speech.

“While the count was alive, he kept you focused on the task at hand. We all hoped that Gregory could assume that role, but he lacked something that his father possessed, or maybe the relationship with you that he established when you both were young made it difficult for him to rein in your whimsical behavior.”

“What ‘whimsical behavior’ are you talking about?”

Before continuing, he repeatedly took the Lord’s name in vain, and petitioned the Father to condemn me to perdition. “Your crazy idea of traveling to Poland, what else? You pictured yourself preaching the gospel to strangers whose ways you could never understand in a language that you could never pronounce. Then, to top it off, you decided that you, the Supreme Pontiff of the Christian Church, needed to marry Count Gerard’s daughter. Despite the fact that you had spent only a few hours together, you proposed to drag her to Poland with you. You even persuaded her to go along with this preposterous scheme. I was desperate to stop it. So I directed my wife to slay Tigra with that very dagger that lies in your lap.”

“You did what? She did what?” I screamed as I dropped the dagger again.

By this time his voice was barely a whisper. “You heard me. She stealthily pricked Tigra with the dagger, which at that time was drenched with a toxin that worked much more slowly so as to mimic a disease. At the time I judged that we had no choice, and I still feel that way. It was the only way to get you to refocus on your role in the plan. It caused a some serious problems, but in the end it had the desired effect. I have no regrets that we did it.”

These obvious lies almost caused me to lose my temper. In deference to his condition I remained as still as possible, but I heard my voice crack several times.

“You did no such thing. You are only trying to provoke me, and it will not work. You know very well that I have never intentionally injured a fellow Christian or any human, for that matter. Neither have I ordered or encouraged anyone else to do so. I am not about to commit a mortal sin just because you succeeded in incurring my wrath. I strongly advise you to devote your remaining time to making your peace with the Almighty. It is never too late for you or any sinner to find the salvation that Christ gave his life to provide us.

“Goodbye, and may God have mercy on your soul.”

I retrieved the dagger from the floor, wrapped it back up in the cloth, arose from the chair with the package in my hand, and walked resolutely toward the door. He thundered curses at my back, but I closed the door behind me and stumbled out of his chamber.

Gerard’s words had shaken me to the quick. Seven different emotions flashed through my heart in rapid succession. My mind nearly stopped functioning, and I felt dizzy. The simple act of placing one foot in front of the other required all of my concentration.

Fortunately, Brother Clement soon arrived to take me by the shoulder and guide me to another room. He sat with me and spoke in a very soothing voice. “Saying the last goodbye to someone is always difficult. Your expression indicates that your conversation with your old friend Gerard was not pleasant. How about a change of pace? If you feel up to it, I would like to introduce you to one of our novices. I think that you will like him. What do you say?”

I probably muttered something, but I do not recall what. He sat me down and left me to my thoughts for a short period. He returned with another much younger monk. “Theophylact,” he said, “have you met Fr. John? You might have known him by another name.”

At first I did not recognize him. His Pauline tonsure and his beard dramatically changed his appearance. Then it struck me. Standing before me grinning was my son, the deposed Supreme Pontiff, Benedict X.

“Your Holiness, ...” I began.

“No, those days are over, never to return. I have a new calling here at the monastery. In their quiet way the monks have convinced me that it is as important as my previous one. Maybe more so. I have learned that I can do the Lord’s work without being the focus of attention.”

Brother Clement filled the gap in the conversation. He addressed me: “Theophylact, I have a proposal for you. Why not join us here at the monastery? You can certainly accomplish more here than you have in the last few years. Our simple life may suit you; I think that It will. Let us put our hands together and join forces.”

Brother Clement extended his right fist, and Brother John placed his right hand over it. It was another whimsical behavior, but I felt compelled to extend my own right hand to seal the pact. I then noticed with a start that the large bony hand of my son was almost a perfect match for that of Brother Clement, and my own hand completed the set. I withdrew my hand involuntarily, looked deeply at the aged monk, and exclaimed, “Why, you are ...”

Brother Clement quickly cut me off. “That is correct,” he said. “We are a real family here in Grottaferrata[9], and we are very happy to have you join us again.”

My friend and protector Gerard survived another six days, ample time for sanctifying grace to penetrate his shell of resistance. The monks cared for him as well as they could, but not much could be done for his physical injuries. He refused to utter another word, not even a curse, to anyone.

[1] Santo Lucà, a scholar at Sapienza in Rome, recently wrote a monograph concerning a set of anonymous scholia that he had discovered in the archives at Grottaferrata. The margins of the manuscript contained a conversation between two people identified by Lucà as St. Bartholomew of Grottaferrata (the hegumen) and Pope Benedict IX (the purported author of this text).

[2] No trace of the city remains today. It was conquered, sacked, and flattened in 1191 by the Romans. Ruins of ancient Tusculum have been unearthed recently, but the archaeologists discovered nothing of note from the medieval period.

[3] The expletive in the text involved Minerva’s possession of something that could be found in no dictionary.

[4] Leo II was Bishop of Velletri from 1032-1038. At this point he would have been dead for two decades.

[5] The master of ceremonies for a pontifical investiture is called the camerlengo. The cardinal entrusted with this responsibility was Peter Damian, but he and the other members of the Reform Party had fled from Rome when Pope Stephen IX died.

[6] If true, this may have been the first case of a pope fathering another person elected to the papacy. One contemporary source claimed Pope Anastasius I (399-401) was the father of the next pope, Innocent I (401-417). Liutprand wrote that John XI (931-935) was the illegitimate son of Sergius III (904-911).

[7] Benedict X is currently considered an antipope. The “Gerard” mentioned here is Pope Nicholas II, who reigned from January 24, 1059, through July 27, 1061.

[8] Ovidio Capitani, probably the greatest expert in the world on Pope Benedict X, has written that there are at least three contradictory sources concerning the unfortunate pontiff’s fate. The Annales Romani, which Capitani called “fantastici,” claimed that he was divested, excommunicated, and imprisoned in the church of St. Agnes only to be released and forgiven by Pope Gregory VII (Hildebrand/”The Toad”). Leo of Ostia said that he was defrocked but not excommunicated and was held in St. Mary Major. Bonizone reported that he publicly admitted his guilt and was defrocked. Neither Leo nor Bonizone give any indication of how or when he died. The account in the text is not consistent with any of the three extant reports, but by the same token each of them is contradicted by the others.

[9] The Catholic Encyclopedia says this: “... it is more probable that the truth lies with the tradition of the Abbey of Grottaferrata, first set down by Abbot Luke, who died about 1085, and corroborated by sepulchral and other monuments within its walls. Writing of Bartholomew, its fourth abbot (1065), Luke tells of the youthful pontiff turning from his sin and coming to Bartholomew for a remedy for his disorders. On the saint's advice, Benedict definitely resigned the pontificate and died in penitence at Grottaferrata.” The “monuments” mentioned here were destroyed by allied bombing in World War II.