Chapter 10: Breaking the Crusading Habit

Sloppy II’s

The use of the word “First” alerted savvy readers that the saga of the crusades might not end with the siege of Jerusalem. Indeed, there were eight or more crusades to the Holy Land as well as numerous others. The eight popes who served during the fifty-seven years between the start of the First Crusade and the papal call for an encore were a peculiar group with numerous common attributes:

• All were “seconds:” Urban II, Paschal II, Gelasius II, Callixtus II, Honorius II, Innocent II, Celestine II, and Lucius II. Moreover, two antipopes, Celestine II[1] and Anacletus II[2], also boasted very strong claims.• All eight popes supported reforms and strove to eliminate the right of investiture.

• Since the cardinals were no longer exclusively Roman, they often chose outsiders as pope. Due to the Romans’ intolerance of foreign rule, most of the II’s were unable to spend much time in Rome. Many Romans longed for the republic they enjoyed before Julius Caesar. This was on no pope’s agenda.

• Largely cut off from Rome and the patrimony of the Papal States, the popes needed to concoct imaginative ways of funding their activities.

• Many were monks.

• Popular antipopes continually made life miserable for the men designated by the Church.

• Several popes either tried to persuade princes to fight for them or led armies of their own. Pope Urban II’s European truce was ignored. • Toward the end of the period, the powers behind the throne were a chancellor named Aimeric and his loquacious monastic ally, Bernard of Clairvaux.The First Crusade enhanced the papacy’s prestige throughout Europe, but it gained the institution little respect in Italy. The pontificates of the II’s faced more difficulties than one might expect after the triumphant crusade. Their individual acts merit a quick glimpse.

Urban: In 1093 King Philip of France, who avidly supported the exiled pope, married the Countess of Anjou, despite her previous nuptial. Urban waited two years for a politically expedient moment to excommunicate the sovereign for this flagrant bigamy.

Paschal reached an agreement with Emperor Henry V in 1111. Henry agreed to forfeit the right of investiture; in return the bishops were to cede their lands and income to the emperor. In effect the bishops would become, like Pope Paschal, indigent monks. The arrangement, unfortunately, was denounced by the well-heeled German bishops. Henry, who needed their support, blamed the pope and even took him prisoner. After a month or two of incarceration the pope said “uncle” and reaffirmed the emperor’s right of investiture. Pope Paschal later officially withdrew this privilege, but Henry continued to exercise it anyway.

On the very day that he was elected to the papacy Gelasius was seized by members of an opposing faction in Rome. Other Romans soon acted to effect his release. The emperor later set up the Archbishop of Braga as an antipope in Rome. Eventually Gelasius was forced to flee to Pisa, which is where he died.Callixtus successfully consolidated his power and excommunicated Emperor Henry V. The antipope was taken prisoner. The emperor, hoping to get back in the pope’s good graces, renounced the right of investiture in the Concordat of Worms. Aimeric was appointed chancellor in 1124.

The next pontiff Lucius also failed to celebrate even one anniversary. He died from wounds incurred in a battle with the Roman citizenry.

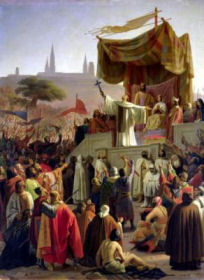

Sewing on the Cross Again

The Second Crusade: The heavily fortified Christian outpost of Edessa fell to the Turks in 1144. Pope Eugene III, who succeeded Lucius II and ended the string of II’s, recruited his mentor St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the most eloquent man in Europe, to drum up support for a crusade to rectify the situation. The saint’s golden tongue and reputation for miraculous cures convinced two armies to take the overland route to Constantinople. The first contingent, led by Holy Roman Emperor Conrad III, set out with seventy thousand armed men in 1146. His brother-in-law, the Byzantine emperor, provided “guides” who deliberately led the westerners into the Cappadocian mountains. Nine tenths of the force was struck down by hunger, disease, or Arabs. A guy I know bought a car from his brother-in-law; same thing happened. The French force, led by King Louis VII, joined up with the surviving Germans in Nicea. Together they journeyed to Jerusalem. After performing the requisite devotions in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, they headed for the previously allied city of Damascus before approaching Edessa. Their siege of the Syrian capital failed, mostly due to internecine squabbles. Conrad and Louis became bitter enemies. The emperor returned home in September of 1148. The king threw in the towel the next year.Many more Jews were killed; the King of France and his wife had such a horrible spat that they returned on separate ships;[5] thousands died; the crusaders never reached Edessa; the two most powerful Christian rulers became enemies. In short, the Second Crusade was a consummate fiasco.

St. Bernard explained the result as God’s punishment for the many sins of the crusaders. Perhaps saints have a special knowledge of the intricacies of God’s plan for deciding which mortals deserve worldly punishment and which merit rewards. Sr. Mary Immaculata never explained how He decides the winners and losers of wars and whither to direct hurricanes, tidal waves, earthquakes, and plagues in order to reward the righteous and smite the wicked. His choices since Sodom and Gomorrah are puzzling.What could be more heinous than the atrocities perpetrated by the original crusaders? Certainly nothing in the Second Crusade ranked with the relentless extortion and pillaging of the “People’s Crusade,” not to mention the heaps of charred and blood-soaked bodies after the siege of Jerusalem. Yet the Lord rewarded those stalwarts with a resounding victory, not to mention a jaw-dropping trove of Egyptian booty. I remember how often Sr. Mary Immaculata emphasized that the Lord works in mysterious ways. If, as Bernard implied, He determined the outcome of these first two crusades based on the propriety of the crusaders, the scales of divine justice might need recalibration.

One might as well look on the bright side. The sins of the second batch of crusaders were once again covered by the pope’s blanket indulgence.

The Third Crusade: Jerusalem finally fell to Saladin and the Saracens in 1187. Pope Urban III died just after the news of the demise of Jerusalem reached Rome. This shocking blow to Christianity may, in fact, have precipitated his demise. The crusade to recapture the city was initiated in 1189 by Pope Clement III. The westerners spared no expense and sent a team of all-stars with three outstanding co-captains:All did not proceed according to plan. On the way to the Holy Land, Frederick Barbarossa,[6] who, despite his seventy years, was still full of vinegar and was an irreplaceable inspiration to his troops, drowned in a freakish accident in the Saleph River. Soon thereafter, much of the imperial army deserted. His son, also named Frederick, perished in a plague in October of 1190. Before the real fighting even began, the feared German army had disbanded. The English army won back Cyprus and was victorious in a few battles on the mainland. However, the cooperative spirit of the First Crusade was absent. Instead, the old feudal habits of distrust, double-dealing, and selfishness prevailed among the Europeans. In fact, near the end Duke Leopold of Austria even captured King Richard and turned him over to the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry VI. The English ransomed their king in 1194.

The Third Crusade was a failure but not a catastrophe. The European outpost of “Outremer” was at least preserved, and Saladin no longer seemed invincible. Nevertheless, when the French and English gave up and departed, the Muslims still held Jerusalem. The massacres inflicted by both sides were legendary in their brutality.

The Fourth Crusade

Lotario de’ Conti was only thirty-seven years old when he became Pope Innocent III on February 22, 1198. The youngest cardinal had not even been a priest on February 20. No Holy Roman Emperor ruled on his legitimacy because Henry VI had died in the previous year, and his heir, another Frederick, was only three years old. Innocent took advantage of the power vacuum to consolidate the papacy’s authority throughout Italy. He persuaded Frederick’s devout mother, Constance, to surrender authority previously reserved to the emperor. Just before her own death, she even named the pontiff himself as the royal toddler’s guardian. Almost immediately the young pope with the jug-handle ears felt secure enough in his own power to petition European leaders for another crusade. The kings all took a pass, but a considerable number of nobles – mostly from France – enlisted in the cause. There would be no three-thousand-mile hike for this group. The Venetian fleet was requisitioned for the princely sum of 94,000 marks to transport nine thousand esquires, 4,500 knights with their horses, and twenty thousand infantry to Egypt. In addition, the Venetians agreed to furnish the crusaders with provisions for nine months.The recruits sewed crosses on their tunics in Venice. Then they passed the helmet. Nearly every crusader contributed his last sou, and the pope himself directed 10 percent of his income to the crusade. Nevertheless, they were only able to scratch up a little over fifty thousand marks, scarcely half of what they needed. What to do? They couldn’t sell blood; soon enough they would need all that their hearts could pump. A bake sale was out of the question; the Venetians have always preferred polenta to biscotti. A mutual fund indexed to the futures markets for indulgences might have worked, but no one thought of it.

Enrico Dandolo, the Venetian doge, was sightless and in his tenth decade, but he was evidently quite sprightly. The crusaders explained their financial plight to him. He reacted as would any seasoned vendor of transportation: he agreed to bring their offer to his sales manager. While he and his guide dog were dickering with the imaginary boss in the Palazzo Ducale, Venetian counselors advised the crusaders to contemplate the Bridge of Sighs – and whither it led. Well, they probably would have if the bridge had existed in the early thirteenth century. Dandolo presented the sales manager’s counteroffer to the crusaders. The piety and sincerity of the crusaders moved him to reduce the fee under one condition: the crusaders would aid Venice in the capture of Zara, a city on the Dalmatian coast then controlled by the Christian King of Hungary. The pope’s legate, Cardinal Capuano, protested the proposed digression. He threatened the crusaders with a papal excommunication if they consented. Some demurred, but most saw no alternative to the Venetians’ scheme. Dandolo himself received the cross in a solemn ceremony in the basilica. His impassioned speech in Piazza San Marco inspired a good number of Venetians to take the crusader’s oath and enlist in the holy mission.

An historic moment occurred mid-voyage. In an exhibition of camaraderie the doge escorted the ex-emperor to the helm of the flagship. Their white canes could be heard clicking on the deck, clearly a case of the blind leading the blind.

Evidently something in the negotiation led the crusaders to expect considerable support from the residents of the Byzantine capital. Perhaps someone uttered the phrase, “They’ll treat us as liberators.” For the one hundredth consecutive time the westerners had misjudged the Byzantines, most of whom had no use for Alexius, especially if he brought Latins to do his dirty work. The Venetians and the crusaders had not come this far for nothing. By gum, they were real crusaders with crosses sewn on their tunics and everything. In 1203 they assaulted the city by land and water. The reigning emperor, Alexius III Angelos, fled the city. The crusaders’ Prince Alexius was crowned Emperor Alexius IV Angelos with no opposition to speak of. The plan was for him to rule with his father, the deposed Emperor Isaac II. “How much did I offer you again?” After perusing the imperial annual statement, Emperor Alexius asked the doge and the crusaders if they would accept an IOU for the balance of his account. He also asked his erstwhile allies to remove themselves to the other side of the Golden Horn – for their own protection, of course. Relations between the emperor and his western escort grew a little strained. The crusaders had meanwhile discovered a mosque – a mosque! – in the middle of Constantinople. Naturally, they burned it down. They might have been a tad careless; the conflagration spread to some adjoining neighborhoods. Don’t waste any sympathy on the citizens who lost their homes; for them it was strictly a matter of time anyway. By 1204 the natives of Constantinople had grown restless. They revolted and overthrew the emperor in favor of one of his courtiers, also named Alexius. During the melee the Emperor Alexius who had hired the crusaders experienced a shortness of breath owing to the rope that the rebels had secured around his windpipe. His father also died shortly thereafter. Alexius V then amassed a large army outside the city. The crusaders mustered to meet it. The westerners were outnumbered, but they must have looked ferocious. The new emperor lost his nerve and brought his troops inside the gates. Pope Innocent III had used the usual clerical channels to send specific instructions to the crusaders not to attack Constantinople, but the chaplains of the expedition evidently decided not to relay the orders to the military. The crusaders breached the walls; the Venetians attacked by sea and accidentally (?) burned down most of the remaining city; the emperor took flight; the people of Constantinople surrendered and offered the entire empire to the westerners.The crusaders relieved their frustrations with three days of sacking. Thus the capital of the Roman empire, founded by Caesar, indomitable for over twelve hundred years, in the end was flattened by men wearing the cross – Christians killing and robbing Christians. The Saracens retained uncontested control of the original objective, Jerusalem, throughout the crusade.

That Crusading Spirit

Pope Innocent dialed it up a notch. Why should the concept of crusade be restricted to the Holy Land?[8] The pope called one against the Cathars. When he offered the usual plenary indulgence to all who wore the cross into battle against them and promised that the crusaders would retain all captured territory, the response was impressive. After all, a sojourn in the south of France held considerably more appeal than the arduous trek to the Mideast. After the last such city had been taken, Pope Gregory IX realized that a few Cathars still remained. He enhanced Pope Lucius III’s Inquisition trick to remove the residual effects of the heresy. The I-word is the focus of Chapter 11.

The Greatest Pope?

Innocent referred to himself as the “Vicar of Christ,” not the “Vicar of Peter.” He professed that the pope could use any means to attain his ends. How else could he encourage if not precisely order the wholesale slaughter of both the Cathars and nearby Christians? Pope Innocent insisted on having his cake and eating it too. His letters and actions are disturbingly inconsistent. He excommunicated the crusaders after the expedition was diverted to Zara. Then he forgave them, but not the Venetians. He warned the crusaders against attacking Constantinople, but he had personally met with Prince Alexius and must have suspected his intentions. When Baldwin IX of Flanders was crowned Byzantine Emperor in the Hagia Sophia after the leveling of Constantinople, Pope Innocent sent him a letter of congratulations. “By the just judgment of God the kingdom of the Greeks is translated from the proud to the humbler, from the disobedient to the faithful, from the schismatics to Catholics.” History proved the pope wrong on all counts in fairly short order.

Here is a synopsis of the rest of Pope Innocent’s stunning legacy:Franciscans: He personally met with the anti-Innocent, Giovanni Bernardone, AKA St. Francis of Assisi. Matthew Paris reported that the pope told Francis to go play with the pigs, and Francis took him literally. Innocent was simultaneously impressed by the monk’s faith and disturbed by his fanatical rejection of property. In the end the pope gave Francis his approval, but he never officially sanctioned the Franciscan order.

The Fourth Crusade: The sack of Constantinople is considered one of the most disgraceful events in Christian history. Christians of the eastern rite never forgave the Roman Church for its role in it. Either the pope was played for a fool by a blind nonagenarian doge, or he was complicit in the murderous assault on a Christian capital.

The Albigensian Crusade: Innocent did little to rein in the crusaders who exceeded his explicit instructions. By the time of the pope’s death in 1216 thousands of Christians and Cathars had perished in the twelve-year effort to eliminate Catharism, but the heresy persisted. Future popes used this crusade as a precedent for ruthlessly suppressing contrarian ideas.The Children’s Crusade: No one defends this fiasco. Pope Innocent cannot be held personally responsible for it, but more decisive action might have nipped it in the bud.

France: Pope Innocent excoriated King Philip II for divorcing Ingeborg and subsequently marrying Agnes de Méran. When Philip repudiated his judgment, the pope placed all of France under interdict. So the French people paid the price – no sacraments for a year – for their king’s divorce. Philip finally relented and brought back Ingeborg as queen. Agnes, living by herself, died shortly thereafter in childbirth. The king’s animosity toward his wife grew even more bitter. He locked her in prison for eleven years, where she was fed only scraps of food. Meanwhile Innocent enjoyed rather cordial relations with Philip. He even invited him to invade England as the Church’s champion!

England: After a dispute over the appointment of the archbishop of Canterbury, Pope Innocent placed England under interdict[12] and then excommunicated King John, who responded by expelling the clergy from Britain, confiscating Church property, and expropriating Church revenues. The pontiff announced that the king was deposed in favor of King Philip of France. King John, an apostate, concocted an amazing trick, “the 180.” He suddenly accepted the pope’s appointment of Stephen Langton, volunteered to go on a crusade, surrendered his entire kingdom to the pope’s authority, and agreed to pay the Church an annual rent! Pope Innocent fell for this preposterous ruse. He called off the invasion of England and wholeheartedly supported King John in his dispute with English barons. He excommunicated by name those who had attempted to coerce King John into signing the Magna Carta. Because London supported the document, Innocent placed the capital under interdict. European kings: When faced with opposition to his decrees, Innocent peppered Europe with excommunications and interdicts. Several kings obtained bootleg copies of King John’s playbook and ceded their own countries to the pope. Since the Bishop of Rome could never actually govern these territories, the kings remained in power and ruled essentially as before.Nepotism: The pontiff, like most of his predecessors, was careful to spread wealth, property, and positions to his family, especially to his brother, Richard.

Indulgences: After Christians enrolled in four crusades to the Holy Land to achieve remission of sins, Innocent made the same offer for the Albigensian crusade. In the Fifth Crusade financial backers became eligible for the plenary indulgence previously reserved for warriors. Indulgences were not for sale yet, but rich people willing to part with enough cash at the right time could obtain one.

The Fourth Lateran Council: This critically important ecumenical council ratified many of Innocent’s notions.

1. Heresy: The council authorized the use of any means to exterminate heresy. It specifically ratified the Inquisition.

2. Transubstantiation: The doctrine that bread and wine are transformed in the mass – not just figuratively – into Christ’s body and blood was integrated into the canon. Sr. Mary Immaculata would have washed my mouth out with soap if I had hinted that this concept would be awfully hard for people to swallow.

3. Auricular confession: Sins must be confessed not just to God but to a priest.

Fifth Crusade: Innocent himself planned to lead this one, but he died before its launch.

Laws: Pope Innocent instituted more legal canons than his fifty immediate predecessors combined.[14]

Papal authority: “Every cleric must obey the pope, even if he commands what is evil; for no one may judge the pope.”

Death: “He was found after his death in the cathedral in Perugia, forsaken by all and completely naked, because he had been robbed by his own servants.”[15]The Holy Roman Empire: Pope Innocent was convinced that no emperor could ever again be allowed to become as powerful as Henry VI. In his papacy’s early years Innocent dismantled the imperial governmental structure in Italy. The German governors were dismissed, and many towns were placed under papal jurisdiction. When the job had been completed to his satisfaction, he finally trotted out his young ward, up until then safely tucked away in Sicily, and designated him as the new King of the Germans. Innocent was evidently confident that Italy now safely rested where it belonged, in the pope’s hands.

Ah, but things did not exactly work out that way. This story is worth telling.

Freddy the Deuce

According to legend, on the day after Christmas of 1194 a forty-year-old woman descended into the main piazza of Jesi, a town a little ways inland from Ancona. She wasn’t there to return presents, and she wasn’t out for a cappuccino and brioche. Her name was Constance, and she was the reigning Queen of the Two Sicilies, a direct descendant of the unstoppable Norman conquerors, and the wife of Henry VI, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Germany and Italy. She was in the piazza to give birth to her son. The youngster was christened Frederick Roger, after his two illustrious grandfathers, Frederick Barbarossa, the greatest emperor since Charlemagne, and Roger II, the King of Sicily, which included nearly all of Italy south of Rome. The world came to know the young man as Frederick II.After her husband’s death Constance had whisked Frederick off to Sicily and dismissed his German tutors and counselors. The loosely supervised imperial heir learned a lot in Palermo. Every culture was represented in Sicily, the crossroads of the Mediterranean. Frederick became acquainted with all of the dominant ones – French, Spanish, German, Italian, Greek, Norman, Byzantine, Jewish, and Arab. A future pope, Cencio Savelli, tutored him, but Frederick was also exposed to a court crowded with Arabs, Sicily’s rulers for centuries before the Norman invasion, and even Jews. There was little chance of indoctrinating the young man with one viewpoint. He considered himself a human being first, a Sicilian second, and an Italian third. Everything else – Christian, German, Norman, etc. – was way down the list.

Frederick’s brain was sponge-like. He became a world-class authority in several scientific fields, especially biology and astronomy. He conducted the world’s first archeological dig. He could read and write seven languages – seven more than the norm in thirteenth century Europe. Italians give their celebrities nicknames. His was Stupor Mundi, the wonder of the world.

While Frederick was absorbing the ways of the world on Palermo’s streets, Pope Innocent maneuvered Philip of Swabia and Otto of Brunswick into a prolonged dispute over the succession to the German throne. In 1209 Otto offered the pontiff numerous concessions in exchange for the imperial crown. He had learned that the best way to deal with Pope Innocent was to tell him what he wanted to hear. However, Innocent did not appreciate Otto’s duplicitous land-grabbing after he became emperor. The pope dropped an X-bomb on Otto and was ready to hand the crown to Philip of Swabia.[16] Philip was assassinated just before the deal could be sealed.Pope Innocent determined that Frederick’s time had finally arrived. With the support of the King of France he persuaded a group of German princes to elect the teen-ager King of Germany in Frankfort in December of 1212. Frederick was crowned in Aachen in 1215. Otto’s death in 1218 left Frederick as the undisputed ruler of Germany. Two years later he was crowned as Holy Roman Emperor in St. Peter’s Basilica by Pope Honorius III, his boyhood tutor. For the ceremony Frederick chose for himself a robe festooned with Arabic inscriptions.

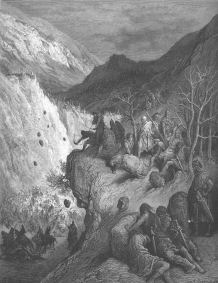

The Fifth Crusade: Pope Innocent called still another crusade for June 1, 1217. He pulled out all of the stops. Not only did he fund the entire enterprise; he also offered a plenary indulgence to those who contributed money to the cause. In addition he forbade the sale of all merchandise – particularly munitions – to the Saracens for four years. Innocent died before the launch. Andrew of Hungary led an army to Syria in 1217. William of Holland departed in 1219 and captured the Egyptian port town of Damietta. The crusaders could have exchanged the town for all of Palestine and the release of Christian prisoners. However, still full of the crusading spirit and anticipating substantial support from Emperor Frederick II, they rejected the offer. “No deal” was the wrong choice. Frederick almost certainly intended to go to Jerusalem eventually. He had solemnly promised Pope Innocent to do so. However, even as a young man he never let anyone set his timetable. His new kingdoms of Italy and Germany required his attention. In his stead he sent Louis of Bavaria with a large German army. Bishop Pelagius, the papal legate to the crusade, directed the combined forces to pursue the Egyptians. Although they substantially outnumbered the Egyptians, the Christians found themselves in a deadly trap during the Nile’s flood season. They withdrew without offering battle. Thousands perished in the retreat as they slogged their way by night through the mud. Bishop Pelagius was forced to sue for peace. He ceded Damietta. The sides exchanged prisoners. The Christians got the True Cross back. Four years and tens of thousands of lives were expended for some wood. The Sixth Crusade: In 1225 Frederick wed Yolanda, the Queen of Jerusalem. The opportunity to add the Holy Land to his empire provided a compelling motive to fulfill his vow to the pope. He set sail in 1227 after missing several papal deadlines. Before departing he deposited with Pope Gregory IX, Pope Innocent III’s nephew,[17] a vast sum of gold against his pledge to fight in the Holy Land for at least two years. After three days at sea many crusaders, including the emperor himself, became quite ill. Perhaps they contracted malaria, which was rampant at the time. They were forced to return to Italy.Pope Gregory excommunicated[18] Emperor Frederick. As soon as this was publicized, the Romans rose up in revolt and drove the pope from the city. He took refuge in Perugia. Nearly all German bishops and princes continued to support Frederick even after the excommunication had been promulgated. No previous papal excommunication provoked such a negative reaction.

When Frederick regained his sea legs, he again set sail for the east. The pope excommunicated him again, this time for departing before obtaining absolution for his first offense.[19] The emperor faced pressing problems on his arrival at Acre in September of 1228. Disease and desertion depleted his army. His wife, through whom he intended to claim the Kingdom of Jerusalem, died in childbirth. Furthermore, the Templars and Hospitallers, two orders of monastic knights who served as the de facto Christian authority in the Holy Land, refused to help the excommunicated emperor regain Jerusalem.

Frederick undertook protracted negotiations with Sultan Al-Kamil. In 1229 they reached an agreement whereby all Jerusalem except for the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque was ceded to Emperor Frederick and the crusaders. They also agreed to a ten-year truce. Frederick had obviously engineered a tremendous victory. He was hailed as a hero throughout Europe. However, the treaty was unpopular in some circles, especially those with a papal focus and a short radius. Crusaders were supposed to win Jerusalem back by faith and the force of arms. The pope had commissioned Frederick to crush the infidel, not to trade camels with him. A more practical consideration was the occupational army’s horribly reduced state. The sultan could probably retake Jerusalem any time that he wished. The treaty also upset many Muslims, who protested that they had surrendered one of their three sacred cities to a force that they could have squashed.Despite the opposition, Frederick crowned himself King of Jerusalem in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. He did it himself because not a single priest showed up for the ceremony. This act earned him his third papal excommunication. The day after the crowning the Archbishop of Caesarea arrived and placed the entire city of Jerusalem under interdict. A furious Frederick repaired to Acre.

By any objective cost-benefit analysis, the Sixth was the most successful of all the crusades. Christian military casualties were low, and the treaty allowed the faithful access to all the holy sites. But it did not feel like a victory. The enemy had suffered no humiliation, and there was no booty. Popes expected emperors to act as their swords, not their agents.

Evidently Pope Gregory felt that the established notion of a pan-European truce during crusades did not apply to this one. While the emperor negotiated, the pontiff deployed an invading army into Frederick’s territory in Sicily. Frederick hastened back to his home island and quickly routed the pope’s troops.

Until his death in 1250, Emperor Frederick contended with and negotiated with Pope Gregory and his successors. They made peace in 1230 and war from 1239 on. At times the emperor held nearly all of Italy and Germany. If Pope Innocent III were not already dead, it would probably have killed him to learn that his ward had become the most powerful ruler since Charlemagne, disdained religion, and openly flouted his nephew’s papal authority. Constructing mental pictures of Pope Innocent III and Gregory IX is not too difficult. They were ruthless, single-minded despots who entertained no doubt about the divinely inspired nature of their callings. Opposing them was tantamount to opposing God’s own will. The astounding Frederick, on the other hand, was complicated and inconsistent. Some historians consider him the first humanist European sovereign, but he also exhibited a ruthless and petty side. Religion played almost no role in his adult life, but he instituted the burning of heretics.[20] He took on many Arabian customs, including the keeping of a harem. He hid his wives away and seemed to use them strictly for breeding. He probably treated his collection of animals better than his spouses. He employed many trusted Saracen advisers, and he brought thousands of Muslims from Sicily to settle on the mainland of Italy. Frederick considered the pope an influential spiritual figurehead who aspired to become a prince by encroaching on territory that was rightly Frederick’s by inheritance. The combination of papal opposition and alliances among the autonomous towns in northern Italy was his major challenge. However, many bishops and cardinals supported the emperor even in the face of persistent papal denunciation. The popes often supported pretenders to his thrones, but Frederick never supported an antipope or considered installing one.The anti-Frederick crusade: In 1239 Pope Gregory excommunicated Frederick again. He even ordered a crusade against Germany, urged the German princes to elect a new king, and placed an anathema on all who supported Frederick. This invective accomplished little other than to steel Frederick’s determination to conquer the Papal States. Gregory called an ecumenical council in Rome at a time when Frederick controlled the territory around the city. Frederick prevented the bishops from attending the council and actually captured shiploads of them when they tried to sneak into town. He then marched on Rome and was just outside of the city when the pontiff expired in 1241.

The next pope, Celestine IV, was the first elected in a true conclave, and quite a conclave it was. Malachi Martin described the actions of the Senator of Rome, Matteo Orsini, thus:First, he had the cardinals brutalized by his own men. Each cardinal was tied hand and foot, flung to the ground in the presence of eyewitnesses (to instill a sense of shame), struck and beaten as if he was a thief and a felon, stomped on by the soldiery, and abused with foul language: “Sacco di mierda! Reverendissimo Cardinale!” was the expression each cardinal heard as a military boot ground his face into the mud.[21]

The cardinals were then thrown together into a sparsely furnished room into which no one – not even a doctor – was allowed entry. Garbage and worse flooded the hall. One cardinal almost died.[22] They elected Cardinal Humberto Romano, who promised to resign as soon as they all escaped. Orsini, however, saw through the ruse. He threatened to dig up Gregory IX and throw his carcass in with them. Even after he threatened to kill them all, the stubborn cardinals waited three weeks to name the next pope. Pope Celestine IV only survived for a couple of weeks. By then, the cardinals had dispersed; they made no attempt to elect a pope for two whole years.

As a cardinal in Genoa, Sinibaldo de Fieschi had been a Ghibelline (the Italian faction that generally supported the emperor) and enjoyed cordial relations with Emperor Frederick. However, once he assumed the papacy in 1243 as Pope Innocent IV, he resumed Pope Gregory’s crusade against Frederick. He summoned the Genovese fleet to Civitavecchia. He then disguised himself as a soldier and made his way to the port. He boarded a ship incognito and sailed to France. He then established a more defensible papal headquarters in Lyons.Pope Innocent convened a council of bishops, which announced that Frederick had officially been deposed. A bizarre papal bull claimed that not only had Constantine donated all of western Europe to the papacy but also that even in the fourth century, imperial authority had been derived from the Church. This interpretation postulated that the Bishop of Rome, who before Constantine’s time had never had the slightest influence on imperial policy, had always been the civil as well as spiritual ruler of Christendom. Pope Innocent claimed that power had been donated by Pope Sylvester I to Constantine, not the reverse. Of course, it is easier to say it than to make it so. The pope wangled the election of two men as successive Kings of Germany, but neither seriously threatened the emperor.

Frederick II’s long career included a few significant military setbacks. Milan, for example, was a persistent thorn in his side. On the other hand, despite all the papal posturing, excommunications, and depositions, at his death in 1250 Frederick still firmly controlled the empire. Pope Innocent IV was still in exile.

Louis, Louis[23]

The last two crusades with the purpose of recovering the Holy Land were the low birth-weight brainchildren of King (and Saint) Louis IX of France. A humble and deeply religious man, Louis had unsuccessfully tried to broker peace between Pope Innocent IV and Emperor Frederick II. Poorly cast as the King of France, Louis was nothing short of a disaster as the leader of crusades.

The Eighth Crusade: In 1267 Louis heeded the calls of Pope Urban IV and Clement IV for a crusade. By then the westerners remaining in the Holy Land battled one another with disturbing regularity. This naturally diminished their ability to defend their holdings against the Muslims. In 1268 Antioch fell.

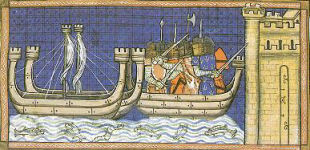

Louis departed in 1270 with sixty thousand men. They sailed to Tunis, not to the Middle East, probably because Charles wished to reclaim Tunis as a vassal. In Carthage a large number of crusaders were stricken with a plague. It proved fatal to both King Louis and his son John Tristan. Charles, always strapped for cash, assumed the crusade’s leadership. He helped his nephew, King Philip III, negotiate a lucrative buyout from the emir. After appropriating everything salvageable from the wreckage of Venetian and Genoese ships, Charles abandoned without fanfare the last major crusade to the Holy Land. Instead he organized a campaign against the Greek Christians who had regained control of Constantinople. The Ninth Crusade?: By the time that Prince Edward of England and his pitiful force of 230 or so knights arrived in Tunis, the Eighth Crusade had already been called off. Edward sailed to Acre, engaged in a few skirmishes, negotiated a treaty with Sultan Baibars, and then returned to England with a heroic reputation.Djem’s Djailers

During the next two centuries a few more half-baked crusades were attempted. The medieval popes persevered, but most Europeans lost interest. No scimitar had yet tasted any papal blood. The secular leaders of Europe, whose relatives and subjects had paid the price for these adventures, had had enough. The last Christian stronghold of Outremer, Acre, finally fell in 1291. For centuries Christians had agreed that the crusades had been a worthy undertaking. However, you cannot squeeze blood from a stone. The cost of the crusades was absolutely outrageous, and most gains proved transitory.

Papal support for the crusades endured well into the Renaissance. Pope Pius II died trying to launch one as late as 1464. Shortly thereafter, even the popes began to lose interest in regaining Jerusalem and smiting the Muslims. In fact, …

Important note: I swear on everything that is Oprah that the narrative in the rest of this section is substantially true. The most incredible episode of the crusading movement concerns the confinement of a Turkish noble named Djem. The whole affair is well documented, and Djem himself is depicted on a white horse in Pinturicchio’s Disputation of St. Catherine of Alexandria and Maximian in the Room of Saints in the Borgia apartments in the Vatican.

In 1453 the armies of the great Turkish Sultan Mehmet finally conquered Constantinople. The sultan even converted the greatest church in Christendom, the Hagia Sophia, into a mosque. Mehmet fathered two sons, Bayezid (also spelled Bajazet) and Djem (also spelled Jem, Cem, and several other ways). When the sultan died in a revolt of the Janissaries[24] in 1481, Bayezid succeeded him. Djem waged a military campaign against his brother for the throne. After tasting defeat in a few battles, Djem visited the Knights of St. John (Hospitallers) on Rhodes. The main item on his agenda was to solicit help in overthrowing his brother.Djem remained long enough to father a few children by his Italian wife. Eventually he was handed over to French Hospitallers. They remanded him to Pope Innocent VIII in 1489 shortly after the pope had given the red hat to (i.e., made a cardinal of) Pierre D’Aubusson, the Grand Master of the Knights of St. John. The pope’s deal for Djem included ecclesiastical concessions to both the knights and the King of France.

The pope treated his captive as royalty or at least as an exotic animal. Djem was escorted through town on a white horse by the pope’s favorite son.[25] Djem refused to kiss the pontiff’s feet[26] – as was the custom. Instead he gave him a peck on the papal shoulder. In some ways Djem wasn’t much to look at – short and stout with only one functional eye. He had reportedly killed four men with his own hands. He was nevertheless a prized possession. He occupied luxurious apartments, and his movements were not unduly restricted. Even in captivity he maintained his regal bearing.The popes continually extorted “expense money” from the sultan. Just to keep his brother at bay, Bayezid agreed to pay the pontiff a staggering annuity[27] that almost matched the total income of the Papal States. So, for quite a few years the rich Muslim sultan underwrote a substantial portion of the budget of the Catholic Church!

Innocent VIII’s successor as both pontiff and djailer was the notorious Pope Alexander VI. Innocent may have fantasized about using Djem to reconquer Constantinople and/or the Holy Land, but the pragmatic Alexander fixated on his political and economic value. He forced him to stay in Castel Sant’Angelo. Alexander’s son Caesar,[28] a teen-ager when his dad donned the tiara, enjoyed hanging with Djem, who was approximately sixteen years his senior.Pope Alexander boldly requested much more money from the fabulously wealthy sultan. For this he pledged to take an active role in discouraging the crusades and to keep King Charles VIII of France out of Italy. The sultan feared that the king might inspire the residents there to help him launch a new crusade. He had evidently never read the shortest book in the library, Italian War Heroes.

The plot took one more strange turn right before the finish line. During his invasion of Italy, King Charles VIII of France had the pope at his mercy. Pope Alexander made one last plea to Bayezid for help. The sultan sent a message promising to provide seven and one-half times the usual annuity if the pope arranged for Djem’s death. Unfortunately, this message was intercepted, and it quickly reached King Charles’s eyes. The king let the pope wiggle off the hook, but he demanded both Caesar and Djem as hostages. With no feasible alternative, the pope agreed to the terms.With both Caesar Borgia and Djem in tow, King Charles led his army down the A1 from Rome to Naples. However, Caesar soon effected an escape, and Djem died shortly thereafter in Capua. Some chroniclers wrote that he died from something that he ate. Others insisted that he was poisoned by the pope or Caesar, neither of whom was there.

King Charles’s threatened crusade never materialized. Invading Italy was more than he could handle. Chapter 16 explores this in detail.

[1] The antipope Celestine II was dead by the time that the other Celestine II chose his name.

[2] At the time that Anacletus II was elected, the original Anacletus had not yet been identified with Pope Cletus.

[3] The Catholic Encyclopedia, op. cit., Vol. VII, p. 457.

[4] Ibid., Vol. I, p. 447.

[5] Pope Eugene “commanded them to stay married. He even told them to sleep together and ordered that a luxurious double bed be prepared for them.” David Hilliam, Eleanor of Aquitaine: The Richest Queen in Medieval Europe, The Rosen Publishing Group, 2005, p. 38. The Primate of France later contradicted the pope’s ruling and annulled the marriage as incestuous. Eleanor later married King Henry II of England.

[6] Both the Byzantines and the Saracens were terrified of him; a rumor set the size of his army at a million soldiers.

[7] The bridge across the Bosporus connecting the Asian part of Constantinople with the more cosmopolitan European zone was completed in 1973.

[8] Crusades called by Pope Eugene III against the Slavs and the Portuguese Moors were tangentially related to the Second Crusade.

[9] Johan Karl Ludwig Gieseler, A Text-Book of Church History, Translated by Samuel Davidson, Harper and Brothers, 1857, p. 297.

[10] George Finlay and Henry Fanshave Tozer, A History of Greece, Clarendon Press, 1877, p. 101.

[11] Eamon Duffy, Saints and Sinners, Yale University Press, 1997, p. 119.

[12] It took Pope Innocent over six years to get around to removing the interdict from England.

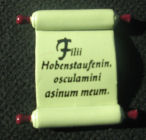

[13] The scroll under his arm reads “Filii Hohenstaufenin, osculamini asinum meum.” A literal translation is “Sons of the Hohenstaufen, kiss my ass.”

[14] De Rosa, op. cit., p. 77.

[15] Hans Küng, My Struggle for Freedom, Translated by John Bowden, William B. Erdesman Publishing Co., 2003, p. 170.

[16] Otto was a Guelph; Philip was a Ghibelline. These two parties dominated Italian politics for centuries. The Papal States almost always sided with the Guelphs. Little more can be said with much certitude. The alliances shifted so many times that comprehension becomes a lifetime struggle.

[17] Pope Alexander III reportedly said that God robbed the clergy of sons, and the devil gave them nephews. Richard Loomis, The Song of Giraldus, Xlibris Corporation, 2000, p. 180

[18] This seems rather harsh. Even the Ursulines would let us go home from school if we were ill. You had to get a note from the nurse. Perhaps Frederick forgot.

[19] This one seems incomprehensible. I do not remember the nuns ever punishing anyone for returning to school after an illness.

[20] Most condemned to this punishment also happened to be the emperor's political enemies.

[21] Malachi Martin, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Church, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1981, p.156. Liz Smith said that Father Martin, later a legendary figure on late night radio, “served three popes as a diplomat and spy.”

[22] Time magazine reported on October 8, 1978, that three out of ten cardinals died. The official Vatican record says that one cardinal died before the conclave began, one did not attend, and thirteen voted.

[23] This is a transcription of the Kingsmen's version of Louie, Louie that I got off of the Internet:

yeh yeh yeh yeh yeh sadday looweeloowhy oh bebay sadday we gowgow

Ayfain liyelkurwl away onee

eektatsh ahip oconstalee

ale wine shit wine all alowe

eenever acow aamay gitome

Aloowee loowhy nanananana heywegowgow

Oh no addeeloowee loowhy oh bebay heddeweegoddegow

Wenite andayo afaildefee

kaykogorld ocontoflee

a on ay shit awayteedair

agul ayrow mowinherrair

Aloowee loowhy oh no heddewegowgow

ya ya ya ya ya sadday loowee loowhy oh bebay heddeweegowgow

OWKAYLITSGITITOOWERITENEOW

teey.... teteeynow ingamymoowabow

theymuppeelow they peepeealow

theypayinarhear my artegen

aymebber ay mebbelayergen

Looweeloowhy ono sadday we gowgow

yeh yeh yeh yeh yeh sadday looweeloowhy oh bebay sadday we gowgow

Ayseddewegoddegownow

Beybeeconnoweekot

Etco!

[24] The Janissaries were an elite military corps that served as personal bodyguards of the sultan. In this era most were captured Christians or the children of captured Christians.

[25] Not a misprint. Pope Innocent VIII sired somewhere between one and eight sons and up to eight daughters.

[26] Cormenin asserts that Djem said that he “would not touch such a dirty baboon.” op. cit., Vol II, p. 148.

[27] Cormenin also claims that the Sultan “as proof of his friendship, sent him (Pope Innocent VIII) rich presents in gold, silver, and precious stones; his ambassadors were also accompanied by thirty beautiful Circassian slaves, whom he generously presented to the pope and his cardinals.” op. cit., Vol II, p. 149.

[28] Not a misprint. Alexander VI acknowledged at least nine offspring. There may have been others.

| |

| |

Bankable Bar Bets

$ All eight popes from the beginning of the First Crusade to the beginning of the second crusade were II’s.

$ Pope Paschal II attempted to remove the emperor’s power of investiture. The emperor threw the pope in jail until he gave in.

$ Theobald Buccapori was legally elected pope in 1124, but he never made the official list.

$ Pope Innocent II was elected in 1130 by only four cardinals. He accepted the election under threat of excommunication.

$ Pope Eugene III not only refused to annul the divorce of King Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine. He prepared a huge bed for them and ordered them to sleep in it.

$ In the Third Crusade Richard the Lion-Hearted was captured by the Duke of Austria and handed over to the Holy Roman Emperor. The English paid a king’s ransom to release him.

$ The participants in the Fourth Crusade burned down the Christian city of Constantinople and then spent three days sacking it.

$ Twenty thousand or so men, women, and children were put to death in Beziers as part of the Albigensian crusade. Most were faithful Christians.

$ In 1212 children started crusades of their own. None of the groups arrived in Jerusalem. The number of their dead is unknown. Five shiploads were reportedly enslaved by Muslims.

$ King John of England started a trend of European monarchs officially ceding their kingdoms to the pope.

$ Pope Innocent III died in the cathedral in Perugia in 1216. He was found nearly naked, having been robbed by his servants.

$ Pope Gregory IX excommunicated Emperor Frederick II for returning from a crusade due to illness and again for resuming the crusade when he recovered. Frederick received his third excommunication for negotiating the acquisition of most of Jerusalem, including all of the holy sites.

$ The first true conclave was in 1241. The Senator of Rome tied up, beat up, and verbally abused the cardinals before allowing them into the conclave.

$ Pope Innocent IV claimed that the pope had always been the temporal as well as spiritual ruler of Christendom. He claimed that his predecessor had ceded authority to Constantine back in the fourth century, not vice-versa.

$ For six years Sultan Bayezid annually paid the pope an astoundingly large sum of money to keep his (the sultan’s) brother in prison.