Chapter 18: What, Me Worry?

“S’ter! When the Protestants and everybody said that the popes and the car’nals …”

“Cardinals, not carnals.”

“Yeah, like the St. Louis Car’nals.”

“Cardinals.”

“What did the pope and the car’nals do to show everybody that the Protestants were wrong about us, and we were better than them?”

“Better than they. No Christian has the right to judge any pope. You know that, Salvatore. When the Protestants turned their backs on the Holy Father, they rejected Christ’s Word, the Gospel. Do you know what happens to people like that?”

“Yes, s’ter. They burn in hell, and the devil sticks them in the rear end with a pitchfork.”

“They are denied the privilege of glorying in the Presence of God for all eternity.”

“What about the popes? Are they in the Presence of God?”

Actually, Sal never posed that last question. How could any Vicar of Christ fail to achieve sanctity?

Pope Petticoat

Alexander Farnese became a cardinal in 1493, the first year of Alexander VI’s pontificate. Everyone knew that he had received his red hat for two reasons: (1) the Farneses were wealthy and highly respected land-owners; (2) his fetching sister Julia was Alexander’s unabashed mistress. Cynical Romans called Farnese “Cardinal Petticoat.” He was quite young for a cardinal, but no one would guess that he had only six birthdays behind him. He was born on February 29, 1468. Even in the sixteenth century February 29 only occurred once every four years.[1]

Cardinal Farnese had been a strong contender for the papacy in previous conclaves. His tact and willingness to function as a team player had forged strong relationships with the Borgias, Julius II, and the Medicis. As the conclave of 1534 began, he had been a cardinal for over forty years. He seemed the right man to clean up Pope Clement’s mess. In this era his illegitimate children[2] were no impediment. Farnese’s election as Pope Paul III overjoyed the Romans. Although the Farnese towns of Viterbo and Orvieto were not within Rome’s purlieu, they had long been papal enclaves, and most Romans considered Cardinal Farnese one of their own. Although he has often been labeled a reformer, his pontificate continued most existing policies. In support of eminent Italian artists he was almost as free with the Church’s money as were the Medicis. He commissioned the elegant piazza on Capitoline Hill from Michelangelo as well as the gigantic fresco of the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, and the Farnese Palace. Pope Paul ventured down one path with very few papal slipper-prints; he consulted astrologers about every important decision and gathered many around him in Rome. Copernicus nevertheless dedicated his paper describing the orbits of the planets to Paul III, one of the least scientific pontiffs.The Holy Father’s children and grandchildren played featured roles. Pope Paul made cardinals out of two of his grandsons, Alexander Farnese, aged fourteen, and Guido Ascanio Sforza, two years older. The pope looked high and low for a nice town to present to another grandson, Ottavio Farnese. Camerino seemed perfect if not for the annoying fact that it belonged to the Duke of Urbino, a Colonna. His Holiness employed papal troops to claim it for his grandson. The pontiff also arranged for Ottavio to marry the emperor’s daughter Margaret.[3] The pope’s granddaughter was rewarded for her parentage with a French prince as a husband.

Pope Paul had a fatal blind spot for his son, Pier Luigi. The pope first named Pier Luigi as Gonfalonier of the papal army, perhaps in recognition of the skill demonstrated in helping the imperial troops sack Rome. The pope allocated Church funds to purchase the town of Nepi for Pier Luigi and then set him up as ruler of Novarra. Shortly thereafter Pier Luigi took over Cervara (purchased by the pope), Capo di Monte, Visenzo di Tesco, Pignena, Mozano, Pianzano, Arlena, Civitella, Valerano, Corchiano, Fabbrica, Borghetto, and Acquasparta. Pier Luigi appreciated his dad’s thoughtfulness, but these were at best Serie C towns. He had hoped for someplace like Milan with its two world class teams, Inter and A.C. Milan. Unfortunately, the Lombard capital was controlled by the emperor, who felt that he had done enough for the pope’s son. He drew the line after donating the towns of Parma and Piacenza, until then part of the Duchy of Milan. The emperor bestowed the towns on Ottavio, not Pier Luigi, but the pope overruled him and transferred them to his son. Pier Luigi bestowed his vision of modernity on Parma and Piacenza by investing in public works and fortifications. He insisted that the noble families move into town to form his court. When they balked, he seized their estates, an act which engendered a bit of resentment. The upper crust of Piacenza conspired to assassinate him, and they succeeded on September 10, 1547. The murder begat a complicated vitriolic spat among the pope, the emperor, and the pope’s two grandsons. When Pope Paul discovered that his grandson Alexander had contravened his clearly expressed orders, he lost it. He summoned his namesake into his apartment and read him the riot act. He knocked the crimson birretta off of the young man’s head and then collapsed in a heap. The irate eighty-one-year-old pontiff died shortly thereafter.Sr. Mary Immaculata held no monopoly on wisdom. One nugget that I picked up elsewhere was this: Never skip a generation when picking a fight.

The Bargain-Counter Reformation

Pope Paul III ran the Church for fifteen years, enough time to do more than seek out astrologically appropriate towns for Pier Luigi. The devoutly Catholic Emperor Charles V had discerned from his time in Germany that the widespread ecclesiastic abuses were a primary cause of the Protestant revolution. He believed that addressing this issue required an ecumenical council with Protestant participation. Pope Clement VII had agreed to call such a council, but he agreed to many things, and he probably never intended to permit questioning of papal authority. By then Luther’s followers trusted councils no more than popes. Maybe the Church could have patched things up with the British, but it is doubtful that Lutherans or Calvinists would have endorsed any convocation of Italian bishops. Nevertheless, Pope Paul heeded the emperor’s advice and called a council at Mantua in 1537. Nothing came of it. He tried again with no more success the next year in Vicenza. With France and Spain constantly at each other’s throats, persuading their bishops to confab was difficult. After the conflict between Charles V and Francis I finally subsided, the Council of Trent convened in December of 1545. Meanwhile Pope Paul set in motion his own scheme for dealing with the Protestants. He can be credited with popularizing the “Blue Ribbon Commission” trick so often employed in subsequent centuries. In 1536 he challenged nine distinguished Roman clergymen to report on abuses in the Church. When their findings were published in 1537, nobody felt compelled to address the problems listed therein.The emperor insisted that the pope dispatch delegates to negotiating sessions with the German Protestants. Some sincere attempts were made to reconcile the various points of view, but the gulf between Rome’s doctrines and the Lutherans was patently unbridgeable. Moreover, new sects frequently appeared, and their beliefs aligned with neither group’s. People had begun to think for themselves about religion. Neither the pope nor Luther would be comfortable with some of their notions.

Pope Paul III’s bull of 1537, “Sublimis Deus,” declared that native Americans should not be enslaved under any circumstances. Although one phrase could be interpreted to imply that the same reasoning applied to other peoples, the bull never specified penalties for violating the edict. Instead it declared all contrary actions “null and void.” The penalties were outlined in a letter accompanying the bull. However, the letter was evidently revoked in 1538 with the brief “Non Indecens Videtur.” So, there was little effect with respect to Indians and none at all for other slaves. The pope surely knew about the practices, but neither he nor any other pope ever excommunicated anyone by name for enslavement or slaveholding.

In 1540 Pope Paul III recognized St. Ignatius Loyola’s Society of Jesus (the Jesuits). The order’s original goal was to convert Muslims, but the rapid spread of Protestantism redirected the focus toward stemming losses in Europe and bringing rebels back into the fold. The rigorous academic standards dictated by the founder made it natural for Jesuits to become the Church’s representatives in theological debates.In 1542 Pope Paul created the Holy Office as the final appeal of the Roman Inquisition. The tools of this new Inquisition resembled its predecessors’. The pope hoped to curtail the Spanish Inquisition’s excesses by assigning the best men available to supervise the doctrines promoted by the new one. He expected to nip errant theologians like Martin Luther in the bud. However, the pontiff’s bull establishing the Holy Office did not repeal the law of unintended consequences. The Roman Inquisition soon became a tool for silencing opposition. Its later targets included scientific thinkers such as Galileo.

Minding Del Monte’s Monkey

Choosing Paul’s successor was difficult. Cardinal Pole of England and Cardinal Alvarez de Toledo came very close to being elected. After months of bickering the conclave settled on the diminutive sixty-three-year-old Cardinal Giovanni Maria Ciocchi del Monte, who was equally objectionable to all factions. On February 7, 1550, he took the name Julius III in tribute to the warmongering pope who elevated him to cardinal. Years earlier Cardinal Del Monte, who had a pet[4] monkey, took a fancy[5] to a street urchin in Parma named Fabian. The way the kid dealt with the monkey impressed Del Monte. He persuaded his brother Balduino to adopt the youngster, who assumed the wildly inappropriate name of Innocenzo. The cardinal hired him to perform menial chores in his household and appointed him provost of the cathedral chapter of Arezzo. His most important assignment, however, was handling His Eminence’s monkey. After his investiture Pope Julius immediately declared Innocenzo to be of legitimate birth, perhaps the most absurd papal decree ever. The seventeen-year-old became the pope’s live-in cardinal-nephew, and he still minded the simian[6] after joining Julius in Rome. This whole episode raised eyebrows. The young cardinal was functionally illiterate and incapable of performing the duties of his office. The secretary of state was therefore assigned greater responsibilities.Innocenzo continued to embarrass the Church after his patron died. A pair of unfortunates evidently dissed him on his way to the conclave, and their insolence cost them their lives. Pope Pius IV arrested Innocenzo and imprisoned him for double homicide. For some reason officials let him out of the pokey a few years later, thereby enabling his rape of an unsuspecting woman. He was again incarcerated, and again he was released through the intervention of Pope Julius’s friends. He died in 1577 and was buried next to his benefactor. The rest of the Del Monte family also prospered from the Julian papacy.

• Three legitimate papal nephews were named cardinals.• The pope’s cousin was appointed governor of Castel Sant’Angelo.

• Balduino was established first in the Borgia apartments and then in the Palazzo dell’Aquilla. He was also named governor of Spoleto and lord of Monte San Savino (after a Medici was removed) and was given the territory of Camerino for life.

• Balduino’s son Giovanni Battista somehow missed out on a red hat. His consolation prizes were the town of Nepi and an appointment as Gonfalonier of the Church.• Command of the Papal Guards went to the pope’s nephew Ascanio.

Jews fared poorly. In 1552 Pope Julius ordered the bishops to collect and burn all copies of the Talmud. He also had the chutzpah to impose a tax on synagogues.

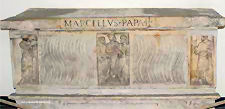

Several chroniclers have accused Pope Julius of being less enthusiastic about poping than about eating, drinking, and other carnal activities. After a couple of years in the job he seemed to lose interest altogether; during the last three years of his pontificate he lived in the Villa Giulia. He decorated it with paintings that would have gotten him investigated for suspicion of pederasty in a less tolerant age.Julius was succeeded by Marcello Cervini de Spannocchi, who took the unimaginative name of Marcellus II. The new pope despised nepotism; for the entire twenty-two days of his pontificate the Church was totally free of it.

“Whatever It Is, I’m Against It”

One might have expected the second conclave of 1555 to seek a candidate with a greater life expectancy. Instead, the cardinals elected Giovanni Pietro Caraffa (often spelled Carafa), a cardinal from Naples who was nearly eighty. One way to characterize his weltanschauung is this: If Pope Leo X liked it, Caraffa hated it. Since the jovial Leo enjoyed almost every aspect of life, the new pope, Paul IV, was truly a hard case. Maybe the conclave expected him to decline the nomination, as Caraffa had once asked Pope Clement VII to resign his own benefices. If so, they were disappointed. Caraffa attributed his election to the direct intervention of the Holy Spirit [Sr. Mary Immaculata: “As always.”], and he behaved accordingly. He named himself after Paul III, who had placed him in charge of the reform effort. His effectiveness as a solitary cardinal was limited. As pope he intended to move heaven and earth to return the Church to the straight and narrow.But first came his family. Paul IV appointed Carlo as cardinal-nephew. By his own admission, Carlo had been a “condottiere,” a mercenary “steeped to the elbows in blood.”[7] Throughout his papacy His Holiness made lucrative provisions for other relatives as well. However, in his reign’s last year the pope became disgusted at the behavior of both Carlo and another nephew, Giovanni, and banished them from his court.

Reforms also were kept on hold until His Holiness could deal with that disgusting country two doors down to the west. The pope vividly remembered growing up in Naples under Spanish dominion. He hated Spain, and he hated Spaniards. He hated Spanish rice, Spanish accents, Spanish moss, and Spanish fly. He hated Aragon, and he hated Castile. He hated tildes, guitar music, maracas, bullfights, and flamenco dancers. He would rather drink mule sweat that Sangria. He considered the Spanish a race tainted by Jews and Moors.[8] All Spaniards were closet heretics. The only thing Spanish that earned his admiration was the Inquisition. He imprisoned the Spanish ambassador in Rome and placed all of Spain, probably the most loyally Catholic country in the world, under interdict. He lined up allies for a war against the Spanish, including the notorious Sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent! When war came, however, King Philip II of Spain marched right up to the gates of Rome. Inhabitants of the nearby towns paid for the pope’s bigotry with their lives. When the French rescued him, the pontiff rewarded them with ten red hats. However, the French troops were subsequently recalled to defend the homeland, and the pope suffered the humiliation of having to sue Spain for peace. King Philip, as devout as the pope, treated the pontiff and the Italians quite fairly.In sixteenth-century Europe hostility toward Spain constituted a poor basis for policy. The Spanish had literally struck gold in Latin America. For decades ships laden with precious metals stolen from the native populations sailed homeward from the new world. Most of the booty was at the disposal of the Spanish monarch. Moreover, the Hapsburgs now controlled, in addition to Spain and Latin America, most of Germany, the Low Countries, large portions of Italy, the Philippines, and various other colonies. Power of this scope and magnitude had not been seen since the Caesars.

While the pope was getting settled on the throne, Emperor Charles V negotiated the Peace of Augsburg with the Protestant Schmalkaldic League. This treaty established the principle of cuius regio, eius religio, which allowed each of the 225 princes to determine the official religion for his territory. Any religion qualified, as long as it was Catholicism or Lutheranism. Families could vote for one or the other, but only with their feet. The Calvinists, Anabaptists, and other sects were still persecuted by both sides.When Charles V resigned the imperial crown, every European sovereign recognized his brother Ferdinand. He had ruled Germany for decades; he was obviously the outgoing emperor’s choice; he was next in line by the rules of succession. Nevertheless, Pope Paul blew centuries of dust off of the claim that only the pope could appoint the emperor and ordered Ferdinand to resign. No one paid much attention.

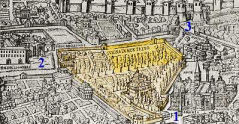

Pope Paul despised heresy. He hated anything with a whiff of Protestantism. He met every Thursday with the heads of the Inquisition to assure himself that everything possible was being done to extirpate it. He insisted that strong, determined action could eliminate it. He dragged both Cardinal Morone and Bishop Sorano before the Inquisition on suspicion of heresy. They both landed in prison. Pope Paul also had a low opinion of Jews. His canon, “Cum Nimis Absurdum” argued that “the guilt of the Jews had consigned them to a life of perpetual servitude.” Perpetual servitude![9] This document also consigned Roman Jews to the ghetto, a walled-in area in a sleazy part of town. It was the first area inundated when the Tiber flooded, a regular occurrence over the next few centuries. All Jews were locked in the ghetto at night. As badges of their race, Jewish men were forced to wear yellow hats and women shawls. Their economic activity was restricted to the rag and bone trade and the making of mattresses. The Roman ghetto lasted for over three centuries through thirty-two pontificates.Pope Paul banished from Rome all traveling entertainers. He outlawed both hunting and dancing. Every sensible person gave His Holiness, who was known as a heavy drinker, a wide berth. He seldom minced words, and despite his advanced age he got physical with people who fell short of his expectations. He reportedly boxed the ears of the governor of Rome, and he forcibly extracted handfuls of hair from the beard of the ambassador from Ragusa. Many Romans – as much as half the population – abandoned the city in fear.

In 1557 Pope Paul published the first Index, the list of prohibited books. By 1948 it included four thousand titles and resembled a reading list for an honors class, boasting the names of such authors as Jonathan Swift, Rabelais, Descartes, John Locke, Victor Hugo, Daniel Defoe, Alexander Dumas, David Hume, Oliver Goldsmith, and all the works of Jean-Paul Sartre.The pontiff’s bitter outlook did not exactly endear him to his subjects. “Upon the death of Paul IV, in August, 1559, the Roman people immediately broke upon the prisons and released the captives, threw down his statue, and cast its head with its triple crown into the Tiber.”[10] Sr. Mary Immaculata would have scolded the unruly Romans. “All popes are instruments of God’s Will.[11] If Paul IV’s pontificate inadvertently caused suffering, that does not negate this fact. We know from the story of Job that the Lord sometimes tests even the most faithful. Hardships often help people find the Lord. Don’t complain about your problems; thank God for the opportunity to overcome them and offer them up to His Will.”

I’ll See Your Pius, and Raise You a Pius

Giovanni Angelo Medici was at best distantly related to the famous Florentine family. In the conclave of 1559 another long impasse between the French and Spanish factions led to the choice of the unprepossessing Milanese scholar with the famous surname. Medici became pope on December 26, 1559, with the name of Pius IV. His public dispute with Pope Paul IV was a plus in the cardinals’ calculations. He quickly granted amnesty to many of Pope Paul’s enemies; Cardinal Morone and others whom Paul had accused of heresy were released.Cardinal Medici had promised immunity to the notorious Caraffas, but as pope he reneged. He arrested several of them, including Cardinal Carlo Caraffa, who was executed by strangulation. Two of his brothers were decapitated. The other Caraffa cardinal was forced to pay a very high fine and put in a prison cell destined to be his last earthly residence.

Pope Pius appointed his own nephew cardinal, but few complained. St. Charles Borromeo was a dedicated reformer whom even critics of the papacy esteemed.Pope Pius brought the Council of Trent to a successful close. He officially endorsed all of its calls for reform of the Church and its hierarchy, but he added the equivalent of “signing statements” that cleverly reserved his right to interpret its findings and suggestions. Not much changed, at least not immediately.

The pope declared it acceptable for a layman with written permission from his bishop to read the Bible in the vulgate (Latin). After only fifteen centuries the Church determined that the Bible was fit reading for a (registered) lay person. Pius also promulgated rules for booksellers.

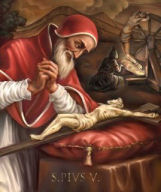

The conclave after Pope Pius IV’s death in 1565 selected a compromise candidate, Michele[12] Ghisleri, a native of Lombardy with no political connections who was known for his squeaky clean record and fanatical devotion. He prayed almost incessantly, wore a hair shirt for self-abnegation, and enthusiastically supported the Inquisition. He owed his election to complex maneuvering to thwart the erstwhile jailbird, Cardinal Morone. The new pope, who received the tiara on his sixty-second birthday, named himself after his predecessor. However, in attitude and temperament Pope Pius V more closely resembled the fanatical Pope Paul IV, who had appointed him bishop in 1556 and cardinal the next year. Pius V nullified the criminal charges against the Caraffas, but several had already been executed. Pius V was personally humble, but his adamant claim of papal supremacy lent him an arrogant air. He even insisted on the pope’s right to name every prince as God had allowed Adam to name the animals. Doctors were forbidden to treat unrepentant sinners; anyone seeking medical care was first required to go to confession. This might have been a blessing. Sixteenth-century medicine probably killed as many as it cured. The pontiff established a police state to enforce orthodoxy. Spies and informers infiltrated the Papal States seeking news of anyone who had blasphemed or voiced opinions contrary to Church doctrines. Adultery was not tolerated at all – in Italy! Pope Pius attempted to ban prostitution in Rome, but the pay-for-sex industry had become so integral to the city’s economy that he reluctantly backed off. He also rewrote the missal and the breviary. Pope Pius excommunicated Queen Elizabeth of England and tried to persuade King Philip II of Spain to invade Britain and overthrow her in favor of Mary Queen of Scots. He once pledged to spend the entire Church treasury and even to liquidate its assets for the proposed expedition against England. English writers have long claimed that the pope hired an assassin to kill Queen Elizabeth.[13] Her predecessor, Mary, Catherine of Aragon’s daughter, had been a loyal Catholic, and Elizabeth herself was a Catholic, at least in name, when she was crowned. The pope’s actions helped transform the many Catholics in England into enemies of the state.Pope Pius cobbled together the Holy League of Christian nation-states to resist the Turks. The combined fleet under the command of Don John of Austria defeated the Ottomans in the famous Battle of Lepanto and permanently ended Turkey’s dominance of the Mediterranean.

Mercy was not the pope’s style. The campaign against the Huguenots in France offered no quarter. Huguenot leaders were assassinated by French agents, and tens of thousands of unarmed civilians were killed by the Catholic mob. Pope Pius probably did not personally authorize[14] the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre and the subsequent slaughters that occurred in August and September of 1572, a few months after his death. However, he helped devise and strongly promoted the campaign that culminated in the massacre. Pius also issued harshly vindictive orders concerning captives to the League’s troops, and he praised brutal soldiers such as the Duke of Alba. Few popes exerted more lasting influence than Pius V. He brought a refreshing sense of personal shame to the papacy. Greed, nepotism, and the scandalous behavior that characterized so many pontificates did not vanish, but at least he established a norm. His most lasting legacy, however, was in papal fashion. Prior popes had sometimes favored the crimson of the cardinals. Pius always wore white (usually his white Dominican habit), and all subsequent popes have worn white. Most pontifical accessories – the slippers, the helmet-shaped cap (camauro), the cape (mozzetta), and the wide-brimmed hat (capello Romano) – remained red.Pope Pius V died in 1572 shortly after the Battle of Lepanto. He was canonized by Pope Clement XI 140 years later. I John 4:8 says that “God is Love.” Imagine His surprise when Pope Clement unlocked the Pearly Gates and let in the misanthropic Pope Pius. The stoup beside the Gates must have been very capacious to hold enough holy water to wash all that Protestant blood[15] from the pope’s hands. Perhaps the most astounding fact in all of papal history is that Pius V was the only pontiff in the 609-year period from 1294 to 1903 deemed worthy of sainthood.

Don’t Plan Anything for the Second Week of October

(Cardinal Granvelle) announced that Philip had excluded Farnese, but if he accepted gratefully, the king would support him at the next conclave. Out of consideration for Farnese’s dignity, Granvelle said, he would not read the letter to the cardinals. If they could agree on someone to win on the first scrutiny, there was no need to embarrass Farnese in front of his colleagues. Farnese, at first stunned, recovered quickly and agreed, but only if he had a major role in choosing the pope. Granvelle proposed four names, and Farnese chose Ugo Buoncompagni, who had impressed Philip as legate in Spain. Farnese then went to Bonelli and Borromeo, nephews of the previous popes, to get support for Buoncompagni. Some in Borromeo’s bloc preferred Cardinal Ricci, but Borromeo rejected him because he had a son. When after the election it was pointed out to him that Buoncompagni also had a son, he said that he had not known. The cardinal querying him retorted that the Holy Spirit certainly knew and had not found it to be a barrier to making him pope.[16]

Did Cardinal Granvelle possess such a letter, or was it a ploy to fool Farnese? It was probably a trick, perhaps a scheme of the Medicis. Perhaps Cardinal Farnese confidently assumed that Cardinal de’ Medici’s pharmaceutical cabinet would keep the next papacy short. After all, Ugo Buoncompagni was a septuagenarian when he became Pope Gregory XIII.Pope Gregory was more loyal to his benefactor, Pius IV, than to his predecessor, Pius V. He restored benefices bestowed by IV and annulled by V on various bishops, cardinals, and nobles. Pope Gregory also proposed some lucrative provisions for his illegitimate son, but after the ensuing public relations fiasco he was reduced to asking the Venetian doge and King of Spain to toss the young man a few crumbs.

Pope Gregory was only in office for a few months when he learned of the massacre of the Huguenots in France. He joyfully ordered the Te Deum to be sung, cannons to be fired, and bells to be rung throughout Rome. A commemorative coin was struck with the pope’s image on one side and an angel bearing a cross and a sword near a heap of bodies on the other. The “tails” side bears the inscription, “Ugonottorium Strages 1582,” Latin for “The Slaughter of the Huguenots 1582.” The pope also commissioned three murals from Giorgio Vasari. One was entitled, “The Slaughter of Coligny and his Companions.” A young Jesuit named Tyrell was arrested in connection with the Babington conspiracy to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I. Under torture he claimed that Pope Gregory had promised him that the queen’s assassin would be absolved and would be worthy of canonization. William Parry, a member of Parliament who also attempted to assassinate the queen, claimed that he too had papal sanction.Gregory is best remembered for his calendar. In 1582 his papal edict erased October 5 through 14. The Gregorian calendar was extremely unpopular because rent paid for the month of October bought only twenty-one days lodging. Nevertheless, it was adopted by most Catholic countries within a few years. Great Britain and its colonies, however, did not realign their calendars until 1752. So, for more than a century and a half travelers making a forty-eight-hour journey from Paris to London arrived eight days before they left.

Pope Gregory made the odd pronouncement that because the fetus at that point was not yet human, abortion was not homicide if performed in the first forty days of pregnancy.A much freer spender than his predecessors, Gregory invested heavily in Jesuit universities throughout Europe. He sponsored Jesuit missionaries as far afield as India and Japan. He subsidized the battle against the Turks and refused to be outdone in financing construction in Rome. In pursuit of new income streams, Pope Gregory reprised Alexander VI’s expropriation of the lands of the barons in the Papal States. Unfortunately, Pope Gregory’s son Giacomo was no Caesar Borgia, so the dispossessed barons launched lucrative new careers as highwaymen. The Papal States devolved into anarchy. Helpless to restore order, the pope scrapped his plan, pardoned the outlaws, and reinstated some of the barons. The problems, however, persisted; when Gregory died on April 10, 1585, the papal treasury was empty, and chaos reigned in the Papal States.

Now For Something Completely Different

Before the conclave of 1585 gamblers could probably have secured 100-1 or better odds[17] from the banchi on Felice Peretti, known as Cardinal Montalto. His family had no standing in Italy; they had immigrated from Dalmatia only a few generations earlier. Montalto started life as a swineherd in the Marche. Before the conclave he had been living in retirement on the Esquiline Hill near the Baths of Diocletian. He entered on crutches. Although a bright guy and a good speaker, he interacted with the other cardinals in such a bland and obsequious manner that few took him seriously. Something about the Franciscan monk, however, caught the eye of Cardinal de’ Medici. He twisted the arms of some cardinals and provided for the carnal proclivities of others. Montalto eked out a narrow victory. The result was an extremely bitter pill for Alexander Farnese, who, although only one year older than Montalto, had already worn scarlet for over five decades. Pope Paul III’s grandson was convinced that his seventh conclave would be his last, and he was right. Alarm bells should have sounded when Montalto chose his name. The cardinal’s metamorphosis into Pope Sixtus V identified him as a man of action. The story goes that upon the announcement of his selection he discarded his crutches, straightened himself up, and announced, “Now I am Caesar!” Spoilsports contest this story. Well, if it did not happen that way, it should have. In fact, let’s lose the crutches and roll Montalto in on a gurney. He is sustained only by an IV drip and an oxygen tank. When elected, he rips off his vestments and leaps forth in a form-fitting white outfit with crossed keys emblazoned on the torso. His boots, trunks, and cape are the traditional red. No mask; that would be gauche.Sister Diocletia would have endorsed the quick and ruthless manner in which Pope Sixtus addressed the crime problem. “It had been usual for a pope to grant a general amnesty on his accession; but Sixtus was so far from complying with the custom, that he ordered four malefactors to be executed on the very day of his coronation: two by the axe and two by the halter, declaring that such a spectacle would diminish the crowd of idle and disorderly persons who used to disturb the solemnity of that ceremony.”[18] No half-measures for Sixtus; regardless of age or sex, suspected wrong-doers were pitilessly dispatched to the gallows. The Holy Father was quoted as saying, “As long as I live, every criminal shall suffer capital punishment.”[19] Career-minded prison guards took correspondence courses in wielding the axe; Pope Sixtus showed a particular fondness for beheading. “… over all parts of the country, in wood and field, stakes were erected, on each of which stood the head of an outlaw. The Pope awarded praises only to those among his legates and governors who supplied him largely with these terrible trophies, his demand was ever for heads.”[20]

Pope Sixtus next rectified the financial situation. Expense cuts were necessary, but his best trick was reviving the selling of Church offices. He generated so many new sources of revenue that Castel Sant’Angelo resembled Fort Knox. He funded a flurry of construction that included the Lateran Palace, the Quirinal, the cupola of St. Peter’s, and the obelisks of the Vatican, of Santa Maria Maggiore, of the Lateran, and of Santa Maria del Populo. He situated statues of St. Peter and St. Paul on the columns of Trajan and Antoninus Pius.[21] He erected the Vatican Library, the printing office, and the pope’s quarters in the Vatican. He constructed many beautiful boulevards, including the eponymous Via Sistina. His greatest achievement in infrastructure was his other namesake, the Acqua Felice, which brought fresh water to Rome. If Sixtus V had only been Rome’s mayor rather than the supreme pontiff of the Church, his short rule probably would be remembered as one of the most successful. Ah, but Pope Sixtus also immersed the Church in European politics, and in that arena he failed in all of his stated goals – crushing the Turks, defeating the Egyptians, transplanting of the Holy Sepulcher from the Holy Land to Italy(!),overthrowing Britain’s Queen Elizabeth, and his nephew’s accession to the French throne. That last scheme involved persuading King Henry III to adopt a papal nephew[22] as his heir in place of Henry of Bourbon, a Huguenot. The pope distrusted King Philip II of Spain, the one powerful Catholic ruler in Europe; once he even threatened to excommunicate him. He cajoled Philip into launching the armada’s disastrous invasion of England in 1588. Sixtus had pledged an enormous sum in support of the invasion, but he refused to pay on the grounds that the fleet had never landed on British soil. If his aim was to weaken the Spanish monarch, he definitely succeeded. The legendary Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I of England, allegedly remarked, “I know of but one man who is worthy of my hand, and that man is Sixtus V.”[23] Dream on, Queen Bess! Sixtus secretly commissioned Cardinal Allen to justify her excommunication. English spies obtained a copy of the extremely detailed list of her peccadilloes before it could be made public. Such minutiae aside, Sixtus and Elizabeth would have made an intriguing couple, at least until one or the other ended up on the chopping block. The pope’s sister, Camilla, toiled as a washerwoman before joining the papal court. Someone discovered this embarrassing fact and mentioned it in an anonymous pamphlet. Pope Sixtus offered one thousand sequins and a safe-conduct to the author. The poor sap fell for it. The pope abided by the terms, but as soon as the transaction was completed, the fellow was seized, and his hands and tongue were cut off. No more pamphlets from him.Robert Bellarmine, a brilliant Jesuit theologian and Sixtus’s close confidante, wrote that popes only had indirect jurisdiction over princes and kings. Pope Sixtus threatened to place Bellarmine’s book, Disputationes de Controversiis on the Index for this blatant heresy. The theologian Vittorio met a similar fate.

The Gospel According to Sixtus

Well, sort of.

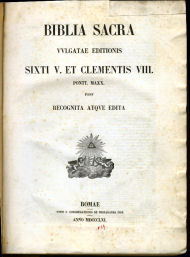

Pope Sixtus defined new divisions of chapters and verses, thereby obsolescing all missals, breviaries, and other liturgical materials. He changed the titles of the psalms. He left out entire verses, maybe through carelessness, maybe through creativity. He even added clarifying phrases when the scriptural text seemed obscure.

The pope’s comparison of the printed text of the first folio against his manuscript revealed many discrepancies. He painstakingly rooted out each problem. He glued little scraps of paper of various shapes onto the folio to indicate corrections. Six months of work produced the final document. The pope then composed a famous papal bull “Aeternus Ille,” presumably intended as an ex cathedra order addressed to all of the faithful, ordering this Bible to be held as “true, authentic, and unquestioned in all public and private discussions, readings, preachings, and explanations.” This bull was included as the preface to every copy of Sixtus’s Bible.

The manuscript was delivered to the printers with no secondary editing and with orders not to deviate under threat of excommunication. The printed volumes were delivered to cardinals and other notables in April of 1590. The reaction was, in a word, muted. Perhaps the cardinals feared the pope’s legendary reaction to criticism: behead now and investigate later. Or maybe they considered him the “crazy aunt in the attic” – best not to say anything that might draw attention to her. Pope Sixtus died four months after the publication.[24] Deaths of important popes often seemed to occur at critical moments.[25] The next pope did not survive long enough even to be enthroned. By the time of Pope Gregory XIV’s investiture, the Sistine Bible had been around long enough for Protestant academics to have discovered some of the errors, omissions, and interpolations. If nothing were done, the Church – and particularly the papacy – might become the laughingstock of Europe. Cardinal Bellarmine recognized the need for swift action. He warned Pope Gregory that the errors must be corrected. The Bible should then be reprinted under Sixtus’s name with his “improvements” quietly removed. The printers and “other persons” could be blamed for the original printing. The pope agreed. Bellarmine and a group of scholars retreated to the country. Bellarmine argued that the new Bible should be published as soon as possible with these disclaimers:1. Pope Sixtus’s original edition had been botched by the printers and “others.” [True only if “others” included the pope.]

2. Pope Sixtus had discovered the errors and asked that a new group start the process again. [A transparent lie.]3. If problems surfaced, they should be attributed to the fact that the working group lacked the Holy Spirit’s inspiration, the pope’s exclusive prerogative. [Was the Holy Spirit napping while Pope Sixtus worked on his manuscript?]

By the time that Bellarmine’s Bible was ready in 1592, Pope Gregory had died, and so had his successor. Pope Clement VIII deviated somewhat from Bellarmine’s plan. He published the new Bible but never acknowledged the previous work despite its unequivocal preface. The task of purchasing, removing from circulation, and destroying all of the originals still remained. What better use for the pile of cash Pope Sixtus left in the treasury than to clean up his mess, which was literally of biblical proportions? So the Inquisition and the Jesuits were tasked with buying back all copies of the Sistine Bible. Unfortunately, only a few were recovered. Dr. Thomas James of the Bodleian Library in Oxford identified a large number of differences between the Sistine Bible and Pope Clement’s version. Since only a few were substantive, and since no one defended the Sistine Bible, so the controversy faded into academic obscurity.

The story had a happy ending for its protagonist, Robert Bellarmine. His book, which Pope Sixtus had banned, was published after the pontiff’s death. Bellarmine was canonized by Pope Pius XI in 1930.

Closing Out the Century

Five years of Pope Sixtus was more than enough for the Romans. By then his name was mud in Rome. He had initiated some showy construction, but much of the awesome wealth that he had amassed remained unspent. The next pontificate would, for the first time in memory, start off with a sizeable surplus, and that made the papacy an even more coveted prize than usual. Although Ferdinand de’ Medici had exchanged his cardinal’s cassock for the princely attire of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, his candidate emerged victorious largely due to the Florentine’s meddling. However, Urban VII’s thirteen-day pontificate, famous mostly for the ban on tobacco in church, is the shortest on the official list. The next conclave lasted two months. The kingmaker this time was Cardinal Montalto, Pope Sixtus’s wastrel nephew. Philip II of Spain had provided a list of acceptable names to his representative, Cardinal Maddruzzo. Montalto cleverly played off the Spanish choices against the papabili of the Colonna family. In the end the cardinals settled on the Cardinal of Cremona, Niccolò Sfrondati, whose two attractive nieces were reportedly the objects of Montalto’s yearnings. The new pope was known as Gregory XIV. Like the Cheshire Cat, Pope Gregory is best remembered for the constant grin that he seemed incapable of removing. His ten-month pontificate afforded him just enough time to use the papal white-out on Pope Sixtus’s bull, “Effraenatum” which had declared abortion to be homicide in all cases. Gregory decreed that Sixtus’s opinion should be ignored; only the abortion of a “quickened”[26] child was sinful and grounds for excommunication. Ippolito Aldobrandini’s election as Pope Clement VIII in January of 1592 was a crushing defeat for King Philip and his candidate, Julius Anthony Santorio, known as Cardinal Santa Severina, the pitiless inquisitor from Calabria. By the last decade of the sixteenth century, banditry was again rampant in the Papal States. Pope Clement reinstated the policy of capital punishment for all suspected malefactors. He made the customary appointment of two nephews as cardinals. None of his five nephews ever produced any male children, so the Aldobrandini line disappeared with the next generation.Pope Clement made peace with King Henry IV of France. The glass was half full: the king converted to Catholicism, so the pope lifted the excommunication. The glass was half empty: the Edict of Nantes gave freedom of religion to Protestants in France. For the pope this meant that heresy had been legalized.

Pope Clement banned smoking, a popular pastime at the turn of the century, from sacred places. Sneaking a drag was grounds for excommunication. He also allegedly called coffee (his favorite beverage) “Satan’s drink.” Evidently Satan was not a morning person. Two memorable events occurred in 1600. Three million pilgrims journeyed to Rome for the Jubilee to receive indulgences and fill collection baskets. Giordano Bruno, a Dominican intellectual who had been excommunicated decades earlier, was burned at the stake in the Campo dei Fiori. Bruno’s writings tended to wax poetic, but they were certainly controversial. His extensive travel and friends in high places helped him avoid the Inquisition. However, in 1592 he was turned in by a student named Mocenigo. After eight years of imprisonment Bruno was convicted of eight counts of heresy by the Holy Office headed by Cardinal Santa Severina. Bruno unsuccessfully attempted to use Cardinal Bellarmine as a liaison to obtain a personal interview with Pope Clement. In the end Bruno was stripped of his robes, gagged, and hung upside-down naked over the flames. His works were placed on the Index in 1603.Pope Clement was obsessed with the prospect of poisoning. Little wonder; neither of the previous two pontiffs had lasted a year in office, and during Clement’s pontificate a man confessed that he had poisoned two popes. Skeptical of the fellow’s firm purpose of amendment; Clement remanded him to the Inquisition for some involuntary penance. Thereafter the pontiff refused to dine alone. If no official dinner guests had been invited, he welcomed beggars from the streets. His Holiness even graciously waived the usual protocols and allowed the barboni to dig in before their host.

In the last years of his pontificate Pope Clement tired of poping and turned over the administration of the Church to his nephew, Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini.

[1] Julius Caesar established leap year. Augustus and others corrected his formula. By Farnese’s pontificate, the calendar was out of synch with lunar phases by several days. In 1556 the Council of Trent, which Farnese convoked, established the current framework. The new calendar was named after Pope Gregory XIII, who implemented the council’s suggestions. Fortunately for young Alexander, Italians do not celebrate birthdays; they honor each “compleanno,” completed year.

[2]

Rendina wrote that Farnese had “numerosi figli, ma legitimandone soltanto tre.” That is, he had numerous children, only three of which he officially claimed. Rendina, op. cit., p. 629.

[3] Margaret had previously been married to Alexander de’ Medici, the illegitimate son of Pope Clement VII. She was almost certainly the only woman in history to marry one pope’s son and another’s grandson.

[4] References to popes’ pets are uncommon. Some writers call Hanno the elephant the pet of Leo X, and Pius XII kept some birds, but references to dogs and cats are rare in the papacy’s annals.

[5] Rendina agreed with unimaginative historians that Fabian was probably the pope’s son. They reasoned that there was no other explanation for his coddling of the worthless young man.

[6] How often he spanked the pope’s monkey is not recorded.

[7] Leopold Von Ranke, “The Popes of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries,” reprinted in The Museum of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art, 1835, p. 552.

[8] He particularly directed this irrational characterization toward Emperor Charles V, who was a red-headed Hapsburg born in Flanders.

[9] Dallas watchers know that this is clearly the wrong way to treat a foe who is at one’s mercy. As Jock Ewing famously advised, “You’ve got to leave a man some dignity, J. R.”

[10] Smith and Taylor, The Library of Universal History, 1897, p. 2091.

[11] Using the singular when speaking of the three Persons as a unit is evidently allowed.

[12] His baptismal name was Anthony, and he was best known as Alessandrino because he was the bishop of the northern Italian town of Alexandria.

[13] See, for example, Edmund Burke, The Annual Register, 1874, p. 104.

[14] According to a “historian” named De Thou, it was authorized by the “queen,” by which he probably meant the queen mother, Catherine de’ Medici.

[15] Mankind has plenty of experience at blood removal. Heaven presumably has less.

[16] Frederic J. Baumgartner, A History of the Papal Elections, Palgrave, 2005, p. 125.

[17] Pope Gregory XIV issued a bull banning gambling on papal elections in 1591, but it had little lasting effect.

[18] W. C. Taylor, Romantic Biography of the Age of Elizabeth, R. Bentley, 1842, p. 267

[19] Henry Smith Williams, The Historians’ History of the World, The Outlook Company, 1904, p. 479.

[20] Von Ranke, op. cit., Vol 1, p. 311.

[21] “St. Paul asked St. Peter why he carried a bundle upon his back, to which St. Peter replied that he had made up his mind to leave Rome, fearing to be hanged for cutting off Malchus’s ear.” Norwood Young, The Story of Rome, E. P. Dutton, 1910, p. 314.

[22] When the king balked, Sixtus bestowed on his nephew a cardinal’s red hat as a consolation.

[23] Norwood Young, op. cit., p. 311.

[24] Church apologists maintain that the printed version was never “formally promulgated.” Patrick Madrid, Pope Fiction, Basilica Press, p. 249.

[25] The pope also intended to publish an Italian version of the Bible. King Philip was appalled. Some have even claimed that he poisoned Pope Sixtus. The Gentleman’s Magazine, 1842, p. 43.

[26] Apparently Gregory’s ontogeny assumed that the fetus was inert for the first forty days of conception. Quickening – detectable motion in the womb – was the point for him at which the soul entered the body.

| |

| |

Bankable Bar Bets

$ Pope Paul III was born on February 29, 1468. He became pope in 1534 before his seventeenth birthday (1500 was a leap year in the Julian calendar).

$ Margaret of Austria married the son of one pope and the grandson of another.

$ Pier Luigi Farnese, who participated in the sacking of Rome in 1527, was named Gonfalonier of the Church by his father, Pope Paul III.

$ Pope Julius III made a cardinal out of a teen-aged street urchin to whom he had taken a fancy. Although Innocenzo Ciocchi del Monte was almost illiterate, the pope gave him the most important position in the curia. After the pope died, the cardinal served separate prison sentences for murder and rape.

$ Pope Julius III ordered all copies of the Talmud burned.

$ In 1555 Pope Paul IV named his nephew as cardinal and chief adviser. His experience at that point in his life consisted of being a mercenary “steeped to the elbows in blood.”

$ Pope Paul IV imprisoned the Spanish ambassador in Rome for the crime of being Spanish. He also placed the entire country of Spain under interdict.

$ Pope Paul IV confined the Jews in Rome to the ghetto.

$ Only one pope who served between 1294 and 1903 was canonized a saint, Pius V. He has been accused by many Englishmen of hiring assassins to kill Queen Elizabeth I. He also plotted the extermination of the Huguenots in France.

$ A Jesuit named Tyrell testified – under torture – that Pope Gregory XIII had said that the assassin of Queen Elizabeth deserved canonization.

$ In the seventeen century anyone who sailed from Paris to London in less than ten days would arrive before they left.

$ To raise funds Pope Gregory XIII expropriated lands from the barons in the Papal States. Many became criminals and highwaymen, and anarchy reigned.

$ Pope Sixtus V ordered two criminals hung and two beheaded on the very day that he became pope.

$ Pope Sixtus V asked King Henry III of France to adopt his nephew so that the young man could inherit the French throne.

$ Pope Sixtus V agreed to pay King Philip II of Spain a huge sum of money to finance the armada’s invasion of England. When the English routed the king’s fleet, the pope refused to pay because the ships never managed to land.

$ Queen Elizabeth I of England is said to have remarked, “I know of but one man who is worthy of may hand, and that man is Sixtus V.”

$ A pamphleteer mentioned the fact that Pope Sixtus V’s sister had been a washerwoman. When the pope discovered his identity, he had the man’s hands and tongue cut off.

$ Pope Sixtus V rewrote the Bible. Erasing this fact from history was one of St. Charles Borromeo’s greatest accomplishments.

$ Pope Clement VIII feared that he might be poisoned. He used unsuspecting beggars as food-tasters.