I swear that I saw a guy taking a leak on a fence in the park as we drove by.[1] Unfortunately my camera was still in its case. I felt like one of those people who sighted Bigfoot.

Our driver was Victor, who had suffered through the trip to Sergiev Posad on the previous day, and the guide was Tatiana, who had conducted the city tour for our group. Tatiana informed us that taking photos inside the Armory or any other building in the Kremlin was forbidden.[2] Bummer. Well, in a way that was a relief. My camera’s good battery was not quite fully charged. At least I would not fret about missing photo opportunities. A light rain started as we left the port area. It took us about an hour to get to the Kremlin, which was much longer than essentially the same drive required on Wednesday. We were told that on Friday all the Muscovites came to work by car so that after work they could drive straight to their dachas without returning to their flats. We also learned that the horrendous traffic jam on Thursday may have been caused by a mosquito. A young driver ran into a lamp post while trying to kill one. Polina told us that inexperienced drivers sometimes placed a sticker with an exclamation mark on the rear window of their vehicles to warn others. Someone put a sticker of a teakettle, the significance of which was evidently lost in translation.Tatiana explained that in the Communist days the dachas were given out to individuals by the trade unions. I wondered how the unions were given the land. Were all the people in one occupation neighbors? How did the party leaders decide which unions got the most valuable land?

The Russia Hotel used to be the largest hotel in Europe.[3] It was torn down in 2006. Work was supposed to begin on a replacement in 2007, but nothing had yet been done. Tatiana said that the big question was whether it would be a five-star hotel.

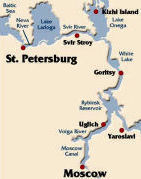

The Kremlin is a triangular fortress. It was originally completely surrounded by water: the Moscow River, a moat, and another river that had been diverted underground.Once Victor had finally let us off near one corner of the wall of the Kremlin, we stood in line in the rain. For the first time in all of my seven vacations to Europe I opened my umbrella. We waited there completely motionless for forty-five minutes. I had my jacket on, and I was still shivering. Plenty of others were coughing. If there had been less traffic, we would have had to wait even longer. They did not open the gate to visitors until ten.

Finally the big hand on the clock on the tower was vertical, and the Kremlin opened for business. Once the line started to move, it was pretty fast. Since the Russian government had many offices in the Kremlin, we had to go through security. The metal detector beeped when I went through, but according to Polina, they know the sound of a bomb.[4] I must have sounded clean.

Our group immediately entered the Armory. The first order of business was to use the facilities. As usual, there was a line for the women’s room. We had to check our jackets with the ladies[5] in the cloakroom. I inserted my cap into the sleeve of my jacket and placed my umbrella in a pocket. The attendant gave me a plastic tag with 409 on it. As I was sitting on a bench waiting for the tour to begin, a passenger whom I had not met came over and asked me “a computer question.” Why he picked me for this I do not know. He had used the software on the ship’s computer to view photos from his digital camera. He had rotated one of the images. I do not know if he saved it or not, but when he later viewed it on the camera, it appeared as just black. I had to confess that I knew nothing that would help him. Actually, I would never have done what he did. At least once a day I downloaded my files en masse and then destroyed them on the camera. I always worked on them using the computer’s software. Of course, if this fellow was using the ship’s computer, he almost certainly did not bring a computer with him. A great advertisement for a Netbook. In a few years no one – not even geezers like us – will travel without a computer of some kind.The first order of business for the tour was ascending three flights of stairs. I could tell without looking or asking that Sue, who had trouble with stairs, already hated this tour.

The first thing that we saw were two familiar coffin covers: one for St. Cyril, who founded the gigantic monastery near White Lake, and one for the patron saint of Uglich, Tsarevich Dimitri.

The biggest attraction of the Armory collection were the Fabergé eggs that had been created for the royal family early in the twentieth century. Nicholas and Alexandra loved to give these eggs as presents to one another. One had their children’s pictures inside. One contained a replica of the royal yacht, Standart, inside. The one that portrayed the Kremlin could produce chimes. One of the most impressive eggs commemorated the completion of the Trans-Siberian Railroad. The train had a platinum engine, and the other cars were gold. Another egg contained flowers that actually opened.We saw the gold cover for the “Trinity” icon of Andrei Rublev (pronounced “rooh BLYOFF”) that was on exhibit in the Tretyakov Gallery. Rublev had painted the icon for St. Sergii himself.

Every Russian crucifix on display had three cross pieces: the usual one for the arms and additional ones for the feet and for the INRI sign.

I wrote some notes about the collection of loving cups, but they made no sense to me in retrospect. Some enameled books from the seventeenth century were on display.Of all the icons, the one of Our Lady of Vladimir was the most venerated. I wondered if it was the icon that was used to stave off the Germans in World War II. Subsequent research indicated that it probably was.

Tatiana insisted that emeralds can be tested in 250 grams of water. Real ones can be seen clearly. This trait was the source of the phrase “of the first water,” which means of better quality. I did not get this; did fake emeralds disappear in water?

The narrow icon that we saw was for a royal baby. It had the same dimensions as an infant and had the baby’s patron saint on it.We inspected a large collection of chain mail, which was commonly worn by soldiers until firearms made it obsolete. Plate mail was very effective against edged weapons, but it was much too heavy to be practical. If a knight wearing plate mail fell from his horse, two people had to help him up. These people obviously never heard of Mithril armor.

The two silver leopards on the right and left of the silver exhibit were actually wine vessels. Salt was too valuable to be passed around to all the people at a banquet. Only those within reach of the guest of honor got to put salt on their fries.Czar Peter I brought baroque pieces back from Sweden. The three-level fountain table had Jupiter at the top.

In the exhibit of seventeenth-century German items, the vases were made from amber. A flagon fashioned from a hollow elephant tusk was displayed. Czar Peter I hated it when people were late, and he made anyone who arrived late for a party drink a tusk full of vodka or rum. To an extent this custom persisted in Russia. People who are late for a party were expected to drink an extra shot.

French tea sets were exhibited in cases. The one with two cups was called a “tête-à-tête.” Every piece in the “Olympic service” was painted with Greek classical scenes. No two were alike.

I notoiced an exhibit of a very small set of armor. No one explained what it was for. Subsequent research has verified that dwarf bowling was not common in Medieval Russia. The armor may have been a gift from the King of Australia.

In the oval room we came upon some sets of chain mail that were used through the seventeenth century, including the mail used by Boris Godunov. One set had a biblical inscription on each link. Another set had mirror-like chain mail that supposedly blinded the enemy. There were also plenty of helmets. The nose piece on one of them could be retracted.We saw the portraits of grand princes, czars, and czarinas. Various orders for medals were on display in a showcase: St. Andrew, the White Eagle, St. George. A book outlined how officers should dress.

A door that we passed had symbols of various towns. I easily located the emblem of Yaroslavl, the bear with an axe on his shoulder. If Tsarevich Dimitri and his knife were there, I did not see them.Tatiana had one very annoying mannerism. Whenever it appeared that people from the group were not keeping up, she would say “Group 45. Over here. Come this way.” She never described where “here” or “this way” was. Her instruction was totally unnecessary for those who could see her. For those who could no longer see her, the information that she was moving did no good.

The so-called “Gospel book” was elaborately decorated inside and out by the monks. She emphasized that the books were all written out by hand. This was not exactly surprising, since before the invention of the printing press the only alternative would be to write them out by foot.

Ornate snuff boxes were created to hold tobacco. Even ladies used tobacco in the eighteenth centuries. It was considered to have health benefits. Maybe so; even in the early twentieth century nuclear radiation was a conventional therapy.We saw an impressive array of crowns, including two plain crowns for Pushkin and his wife. There was no explanation as to why they wore crowns for their wedding ceremony.

Tatiana drew our attention to a display of an icon of St. Nicholas. She said that they took the icon with them when traveling.One book there was definitely unusual. Its cover consisted of a filigree of extremely thin wires of gold.

Tatiana pointed out a big icon of the Madonna with child. Ivan IV gave it to his seventh wife (Tsarevich Dimitri’s mom!) as a present. It was the Lady of Something.

There was a cradle made in Tula for Alexander I, the favorite grandson of Katherine the Great who eventually became czar himself.

All of the Russian museums were nationalized by the Communists.We entered a room that featured a large number of outfits that had been warn by royalty and other important people. The dress for Patriarch Nikon had embroidery made from gold thread. It also contained tiny pearls. The coronation mantle of ermine was only used for the czars. Women wore corsets and wrapped their feet to make them small.

Katherine the Great came up with the idea of the double-headed eagle. It signified that Russia was always alert in both directions in case of trouble from the Turks and the Mongols. Sophia brought the emblem to Russia.[6]

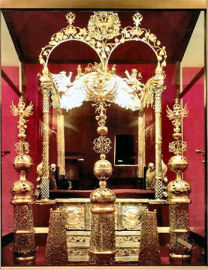

We heard a familiar story about a nun spending months embroidering an elaborate dress. When she was done, she went blind. I wonder if a similar fate had ever befallen anyone working on an illustrated computerized journal.It was considered bad luck for a czar to use a predecessor’s throne. Ivan IV’s was made of wood. Boris Godunov’s was a present from the Shah of Iran and contained lots of turquoise. Ivan and Peter shared a throne because for a while they were co-czars. Peter’s side had a secret door in the back so that Sophia could whisper answers to him whenever he needed to buy a vowel. When he grew up he rewarded her for her help by sending her to New Maidens Nunnery.

The Hat of Monomakh was used to crown the czars. I guess that they all must have worn the same size. It had fur, gold, and precious gems, but there was no band in the back to adjust the fit.The coolest exhibit was the display of royal carriages. King James I of England gave one to Boris Godunov. It could not turn, and there was no bench for the coachman, who had to run alongside the horses. It astounded me that Boris Godunov, who seemed medieval to me, was contemporaneous with the first Stuart king.

There were no screens on the carriages. Katherine the Great was able to make some trip (to St. Petersburg?) in three days because she changed teams of horses. A “troika” is a team of three horses.

Elizabeth II in the eighteenth century was given the carriage with the eagle. Small pieces of steel on it looked like diamonds. It was made in Berlin. A page helped Elizabeth get in and get out. She never wore the same dress twice; I wonder if she reused pages.

Twelve horses were required to pull the gigantic baroque carriage. It had never been restored.

The carriage shaped like a gondola was a present from Count Orlov to Katherine the Great. He proposed many times and gave her many gifts. She accepted the gifts but rejected the proposals. Katherine used Orlov to entice Peter I’s granddaughter to Russia.

Next we moved into the room that had a lot of royal outfits on display. Katherine II had a tiny waist as a young woman, but later, well, not so much. The dress that she wore to Elizabeth II’s coronation had a short train. Elizabeth’s train was much longer.Peter I, who was 6’8” tall, had long legs but small hands and feet. We could see that he patched his own clothes and did his own carpentry.

At the end of the tour of the Armory we went back down to the lobby. I wanted to buy a book with pictures of the exhibits, but there was not enough time. It was hard to believe that tourists were hurried through the gift store. Russians still had a lot to learn about toourism.IMHO this would have been a very enjoyable tour if we had had another half hour and if they had relaxed the restriction on photography.

I quickly retrieved my jacket from the checkroom. We went outside for the walking tour of the Kremlin grounds. The weather had cleared up and also warmed up.We learned from Tatiana that the walls of the Kremlin were about five hundred years old. We marched over to the Assumption Cathedral and went inside. We heard once again what the levels of the iconostasis meant: the top tier was for the patriarchs or forefathers; the second tier was dedicated to the prophets; the middle tier represented the twelve great church feasts; the fourth row was called the Deisis,[7] the lowest tier is for local icons. The title icon is the second to the right on the lowest row.

The doors of the iconostasis were generally closed. The altar was on the other side of the icon wall, which is always on the east side of the church. The illustrations on the west side show the last judgment. The side walls have frescoes of some kind that vary from church to church.The silver chandelier in the cathedral was original. Napoleon used the cathedral as a horse stable. Now it was a museum. There were no organs and no sculpture in any Russian Orthodox churches.

An autopsy performed in 1963 on Ivan IV’s corpse indicated that he had suffered from osteophytes, a very painful spinal problem. At that point in his life his vertebrae may have fused together, and, to make matters worse, the condition might have been treated by mercury. He killed his son and heir Ivan, perhaps by accident. He definitely intended to attack the young man, but he may not have meant to do him in.The belfry, which contained twenty bells, was from the sixteenth century. Because of the hilltop location of the Kremlin, one could see for sixteen miles from the top of the belfry.

We stopped for a few minutes to examine the Czar Bell and the Czar Cannon. Both of them were the largest of their kind in the world, and both of them, like a disarmingly large number of the things that we had seen in Russia, were phony. The bell broke in two before it could ever be rung. It did not just crack. A huge piece broke off and was on display beside it. The cannon was evidently fired at least once, but no one knows when that occurred. The cannonballs that were displayed with it were certainly never used. They weighed one ton apiece! I doubt that the cannon could generate enough thrust to push them down to the end of its barrel.I ventured out into the square to try to take a barrel-on picture of the cannon. This earned me a stern whistle from the guard there. I hustled back to the sidewalk; justice was still swift and stern in this country.[8]

Lenin and Stalin both lived in the Kremlin. None of the other Russian rulers did. Napoleon captured Moscow in 1812, but he could not hold it. He departed in such a hurry that he left behind a large number of his cannons. These were real cannons, but the Russians put them on display in the Kremlin.

We left the Kremlin and trooped over to the corner where our bus was supposed to be. Another group was already there, but their bus arrived almost immediately. There was no sign of our bus. We waited some more. Our hopes arose when a bus came into sight, but it was bus #46. No one was present from that group. So we had an empty bus and a group of restive tourists, but they did not match.

Polina then got impatient with Victor and did something unbelievable. She walked out into the street to see if she could see him. I mean that she was right in the middle of a very busy street in the center of Moscow on a Friday. Traffic was passing on both sides of her. I don’t know how she did it, but she managed to conjure up Victor and the bus without loss of life or limb.On the way back to the ship the bus passed Tchaikovsky Square. In it were a statue of the maestro and the concert hall in which the eponymous piano competition was held.

As we were driving up the Leningrad Highway, it struck me how absurd this approach to seeing Moscow was. We were spending hours in stressful traffic just so that we could eat lunch on the ship before making the same trip again.

I boarded the ship and immediately started recharging my camera’s good battery. I loaded the other one in the camera, which I took with me to lunch. I was therefore able to document photographically that the ship’s buffet had run out of Reuben sandwiches. So I ordered soup and turkey with rice and carrots.Patti and Sue had had their fill of touring. Half of the passengers agreed with them and took the last afternoon off. Tom intended to take the shuttle bus back into the city in search of an Irish pub or two. I alone had signed up for the tour of the Tretyakov State Gallery. I am no art maven, but it seemed to me a waste to come all of this way and not to attempt to appreciate the local art. We had seen plenty of icons and onion domes, but we had viewed almost no painting or sculpture created by Russians.

I fell asleep in the cabin after lunch. I was extremely groggy when I got up. As I stumbled over to bus #41, which was the one designated for the Tretyakov tour, I almost was struck by one of the buses. I found an empty seat on the bus and almost immediately discovered that I had secured my camera case on my belt, but the case was empty. Fortunately I had just enough time to dash back to our cabin to fetch the camera and its spare battery.On the bus trip to the Tretyakov (TREHT yuh koff) Gallery we learned that, as had occurred on the Yusupov tour, we would split into two groups of thirteen. This time the division was done based on which side of the bus we were sitting. My side was assigned to group #41, which would be led by Masha, the lady who had conducted the tour of Sergiev Posad. I did not enjoy that tour much, so I was not thrilled at the news. A man named Sergei guided group #44.

We learned that Pavel Tretyakov had been a very wealthy merchant who resided across the river from the Kremlin. He collected Russian art for himself. He decided in 1892, when he was sixty years old, that all great Russian art should all be organized in one place and gave his collection to the Russian government. A new “block” was added to the building in 1985.The nineteenth century was the golden age of Russian art (and everything else). Paintings from the Tretyakov and the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg had traveled to the United States a few times, but none of them were well known in the West. The avant-garde works of Chagall and his contemporaries were much better known. The museum also contained paintings from the “silver age” and some famous icons.

As we passed the Ukraine Hotel again we learned that Stalin had wanted eight towers, but only seven “sisters” had been constructed. The eighth was supposed to dwarf the Kremlin. The seven included two office buildings, two hotels, two apartment buildings, and the main building of the Moscow State University. In 2010 they were all still standing. No photos were allowed inside the gallery, but photos of nearly every work on display were easy to find on the web. Is there some international policy for determining what can be photographed and what cannot? I certainly cannot figure it out. In Russia you could photograph anything that you wanted in every site that we visited in St. Petersburg except for Peterhof and the Amber Room. In Moscow you could photograph outdoors, but if there was a roof overhead, the cameras were verboten. Of course, the site that had irritated me the most was the Pope’s Palace in Avignon, in which photography had been forbidden even though the rooms were mostly empty. I just do not understand how these decisions were made. Russia had no secular art to speak of before 1700, the time of Peter the Great. Empress Anna created the Institute of Fine Arts in an attempt to stimulate interest. It worked. We started with a room containing several portraits. Vladimir Borovikovsky was a famous painter of portraits in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. We saw his portrait of Prince Kurakin, who, like Pushkin, Borovikovsky himself, and many other upstanding Russians, was a mason.I liked the layout of this gallery. The rooms seemed to be well organized, and the paintings were all labeled. It was easy to take notes and to follow Masha’s commentary, which was full of interesting information. She seemed much more at home in this environment than in dealing with whatever we were supposed to glean from the journey to Sergiev Posad.

We then viewed some paintings by Orest Kiprensky, who lived from 1782 to 1832. His most famous ones were his portrait of Pushkin with a muse behind him and his self-portrait. To me he was a dead ringer for Ralph Feinnes the actor. He also painted Trubetzkoy, who was involved in the Decembrist uprising of 1825.

Alexander Ivanov was awarded a scholarship to visit Italy, and he stayed there for twenty years. What a sweet deal! That was better than veterans’ benefits. I was only able to milk that program for seven years of fooling around in Michigan.

Ivanov devoted most of his time to working on one massive painting entitled The Appearance of Christ before the People that consumed one long wall in the gallery. It depicted the risen Christ approaching a group of John the Baptist’s followers. The slave, easily identifiable by the rope around his neck, had a distinctly green face. Presumably it did not appear so when Ivanov completed the work. Nikolai Gogol, who was in Italy at the time, posed for the bearded man with the brown robe on the far right. The dimly portrayed man in profile right in the middle of the painting is the artist himself. He is the one with the brown beard and out-of-place hat.Ivanov evidently really did work on this painting for twenty years. Three thousand studies and sketches were extant. If you had asked me who created the work, I would have guessed Raphael, who had been dead over three hundred years when Ivanov took up his brushes. We saw a very interesting painting by Karl Briullov called Rider. Both girls in the painting are Italian. The looks on their faces – and their dog’s face – are priceless. The Siege of Pskov, on the other hand showed war as a jumbled mass of humanity.

Semyon Shchedrin specialized in landscapes. He studied in Paris and Rome, but almost all of his works were painted in Russia and depicted the Russian countryside.

Vasily Tropinin’s family were serfs. He was sent to St. Petersburg where he learned artistic skills. His most famous work was probably his self-portrait. Friends eventually bought his freedom for him, but the other members of his family remained in serfdom.

We then got to view Feodor Moller’s famous portrait of Gogol.I think that my favorite artist of all whose work we got to see was Pavel Fedotov, an army veteran who only painted for a few years before he died at the age of thirty-seven. He was one of the instigators of the movement for “critical realism.” His paintings, such as The Major’s Betrothal were pithy vignettes. It was apparent that the characters had been caught in the middle of something unusual, and he used chiaroscuro to draw the attention away from the skullduggery beneath the surface.

I don’t know much about artistic technique or schools. One thing that really struck me during this tour was that what I most appreciated in a painting was its ability to tell a story and to evoke emotion.

Vasily Pukirev’s The Unequal Marriage was a similarly striking rendition of a related topic. The artist himself played an important role; he was the patently disapproving figure on the far right.Konstantin Flavitsky’s most famous work was Princess Tarakanova, in the Peter and Paul Fortress at the Time of the Flood. The subject was the daughter of Elizabeth I and the granddaughter of Peter I. Katherine the Great was afraid that she might try to claim the throne. Alexei Orlov went to Italy, seduced her, and brought her to Russia. Katherine then held her in the Peter and Paul fortress. She did die there, but the actual cause was probably consumption (tuberculosis), not drowning.

Vasily Perov’s Troika was probably my second favorite painting. It portrayed three children who had been sent to the city to work as apprentices. Masha mentioned the Funeral Procession as well. Perov’s portrait of Feodor Dostoyevsky while he was writing Crime and Punishment was his most famous portrait. Hunters Stop to Rest was also displayed in the gallery. There was more to Aleksei Savrasov’s The Rooks Have Returned than appeared at first blush. Rooks were the first birds to arrive in Russia in March. So, even though the landscape looked bleak, the painting evoked hope. Savrasov specialized in paintings of nature.Ivan Ayvazovsky painted Black Sea, Rainbow, and A Moonlit Night on the Bosphurus. Most of his paintings could be found at the gallery in Feodosia, in the Ukraine.

Ivan Kramskoy rebelled against the academy, which exclusively taught the European style. He formed what Masha translated as “The Exhibit Traveling Society.” They were commonly know as the Wanderers. We spent some time viewing Christ in the Wilderness, his portrait of Lev Tolstoy, Inconsolable Grief, a stunning painting of his wife after their two-year-old son died. The painting of an Unknown Lady reminded Masha of Anna Karenina.[9]One of the most popular paintings in the gallery was Ivan Shishkin’s Morning in a Pine Forest. Since Shishkin had never learned to paint animals, he let a friend paint the bears. Friends don’t let friends paint their bears for them. He also produced Rye and Mast Timberwood.

I was bowled over by the work of Victor Vasnetsov. His Tsarevich Ivan on a Grey Wolf seemed at once realistic and eerie. His gigantic work Heroes (Bogatyri) vividly portrayed three legendary warriors known as the Bogatyrs: Ilya Muromets, famous for his strength, Dobrynya Nikitich, the wise one, Alyosha Popovich the cunning. Vastly different but equally effective was his After Prince Igor's Battle with the Polovtsy.At this point in the tour I could not keep one thought out of my head: How could it be possible that I had never heard of any of these incredibly talented, creative, and subtle artists? I guess that the answer was, at least to some extent, that for seventy years the Soviet government was unwilling to share them with anyone else.

Masha introduced us to some works by Vasily Vereshchagin that were unlike any other that we had seen. They Are Triumphant portrayed warriors around a mosque in Samarkand. In front of it were heads of their enemies mounted on poles. He also painted the Taj Mahal Mausoleum, Shipka, and Apotheosis of War. According to Masha travelers found piles of skulls in the Middle East throughout the nineteenth century.The first painter whom I had previously heard of was Vasily Ivanovich Surikov, and that was only because we had walked through his ship for the previous three days. His two masterpieces, Boyarina Morozova and Morning of the Execution of the Streltsy told the bloody story of the religious schism in Russia. The latter shows soldiers of the old Russian army about to be executed. Peter the Great was the stern figure on the horse. The leaders of the rebellion were hung at dawn. Peter asked the ambassadors from European nations to observe the execution of Feodosia Morozova. They were appalled. Masha provided a little history. Patriarch Nikon’s reforms were intended to correct errors in the Russian translations of the Bible and other sacred texts. He commissioned scholars to translate them again from the Greek. For some reason he also changed other customs. For example, he asked the people to use three fingers instead of two when making the sign of the cross. These changes split the Russian society. Millions of Russians had no use for the changes, and some held out for centuries. In 2010 there were eleven churches designated for the “Old Believers” in Moscow. There was a statue of Ilya Repin in the parking lot. His Religious Procession showed mankind at its worse. He painted portraits of the author Ivan Turgenev, the composer Modest Mussorgski, and Rubinstein, his wife, and his daughter. His portrait of Peter the Great’s half-sister Sophia imprisoned in the convent was quite moving, especially when one noticed that a Streltzy rebel hung on a gallows visible through her window. Perhaps Repin’s most famous work was Ivan the Terrible and his Son. Masha seemed to think that the murder had been an accident. Ivan blew his top when his daughter-in-law failed to have her head covered. Ivan attacked her, and his son defended her. Ivan whacked his son with his pointed shaft and killed him. The painting was first exhibited shortly after the assassination of Alexander II. A madman slashed the painting.

Repin’s painting The Ploughman showed Lev Tolstoy, of all people, plowing a field. Repin was extremely popular in his own lifetime. All of the beautiful people requested that he paint their portraits. His other very famous painting, The Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to Sultan Mahmoud IV was on display in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, but some sketches were in the Tretyakov.

Nicolai Ge promoted the message of non-violence found in the New Testament. In What is Truth? Christ remained in the shadows. Ge’s most famous painting was Peter the Great Interrogating the Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich in Peterhof. Peter accused his son of treason and imprisoned him in the Peter and Paul fortress, where he was later executed.I was a little less thrilled with the works in the “new block.” Mikhail Vrubel’s works were full of mystery. To tell the truth, his ceramic fireplace impressed me more than any of his paintings. He based the design on the book Mikula Selyaninovich and Volga.

Nikolai Kuznetsov executed a portrait of Tchaikovsky and tried to give it to the famous composer. Tchaikovsky told him to sell it to Tretyakov because he could probablby get good money for it.

Here is another question. How come so many of these great artists were named Vasily, which is the Russian version of Basil?We walked through the temporary exhibit, but I do not remember anything about it. We also viewed some of the work that was, if not impressionistic, at least influenced by the impressionists. I never have understood impressionism. Impressionistic paintings have never done anything for me; they only reminded me of the way that the world looked when I removed my glasses.

All in all, this was by far the best tour since the ship departed St. Petersburg. Although I was very favorably impressed by the modern Russian painters, I was a little disappointed that we did not get to see the Trinity icon that we had heard so much about. We took a vote, and everyone else agreed that they had seen enough icons for one tour.

We had a little time to ourselves at the end of the tour. I bought a book with professional photographs of quite a few of the paintings that we had learned about. The Trinity icon was on the front cover. I was satisfied.

After that we walked back over the bridge to the spot where the bus had left us off. I snapped a few photos of scenery and a wedding party.

Masha did not return to the ship with us. On the way home Polina explained the Russian education system. School was mandatory through age fifteen. Then two more years of schooling were required before one could apply to a university. Most of the recent university graduates were majoring in management. In the Soviet period most of them concentrated on engineering. If there were no positions available in your specialty, you would need to return to school to get “requalified.” She also reiterated that Moscow had no unemployment.

As expected, the traffic was absolutely horrendous. It took us an hour and a half to return to the ship, and we never left the city limits.

On our return I discovered that Sue had paid our bills and arranged for tips for the staff.At supper we gave a tip to our three primary servers, Julia, Anna, and Louie. The group at the next table sang “Louie Louie.” It was a little unnerving.

I could not remember the word “homeopathic” when the subject turned to quack medicines.

The tour was officially over. Since our transfer bus was not scheduled to leave until 12:30 on Saturday, there was no need to pack. I was asleep by 11:30.

[1] Patti later told me that she saw him, too.

[2] I have given considerable thought to this policy, and I have conclude that it made a lot of sense. When someone is outdoors, his movements can be monitored by satellites and reconnaissance aircraft. If he aimed his camera at something classified, security could be notified immediately. But if the same guy were in one of the museums, he could not be seen from overhead, so, in theory he could photograph classified materials with impunity. All that he would need to do was figure out how to shoot such objects from inside one of the buildings open to tourists.

[3] Actually it was the largest hotel in the world until 1993.

[4] I wish that the security people in the Kremlin would teach this technique to the TSA employees in Windsor Locks, CT. They have often thought that my belt sounded like a bomb.

[5] According to Frommer’s the cloakroom attendants are always female.

[6] Sites on the Internet date its use in Russia much earlier.