For breakfast I ordered a ham and cheese omelet. I topped it off with some fruit and a cup of coffee.

I had just enough time to download my e-mail messages. A couple of the work-related ones were rather disturbing, but there was not much that I could do about them.

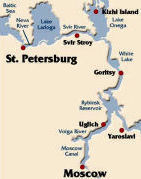

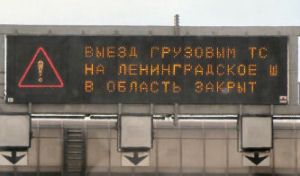

At 8:30 two buses, #41 and #42, were scheduled to leave for Sergiev Posad, a town that was about seventy kilometers north-northeast of Moscow just off of the highway to Yaroslavl. I flipped a coin and got on bus #41. Polina escorted us and introduced a red-haired woman named Masha, short for Maria, as our local guide. The driver was named Victor.Our route was simple. We would take the Leningrad Highway north to the outer ring road, known locally as the MKAD, which we would take east. We would then turn north onto the highway that goes to Yaroslavl.

I overheard one guy on the bus announce that this was the first day that he had worn shorts. Talk about poor wardrobe choices. It had been very warm on Wednesday. In fact, this was really the first cool day on the entire trip. Moreover, Konstantin had told us that the monastery in Sergiev Posad was the only place in which people might be denied entry into the churches if they were wearing shorts. The fellow in shorts fished a pair of rain pants from his very ample backpack and put them on over his shorts. I discovered that I had forgotten the one remaining spare battery for my camera. The good Canon battery was in my camera, and it was fully charged. I was pretty confident that it would suffice unless I was really careless.The big attraction in the town was a monastery devoted to the Holy Trinity, Троице-Сергиева Лавра in Russian . Masha informed us that this was a very strict monastery. She talked of “other confessions,” by which I think that she meant other religions. I was not sure what point she was making.

During the Soviet era the town was known as Zagorsk, and the monastery was converted into a big museum. It was reopened in 1946. I was surprised to learn that Stalin allowed many Russian churches to be reopened during the war.Despite what we had previously been told, Masha said that the patriarch has always lived in Moscow.[1] It was extremely unlikely that he would be in the monastery at the same time that we were.

I saw a really hot blue TT on the MKAD. This turned out to be the high point of my day.

I checked out the prices at a few gas stations on the outer ring road. Gasoline appeared to cost about twenty-eight rubles per liter.[2] The exchange rate was approximately thirty rubles per dollar. A gallon is 3.78541178 liters. So the cost per gallon was approximately $3.53, a little less than the going rate in the U.S.Masha said that the Russian word for “slums” is trushobi (трушобы). The prefabricated units that Khrushchev ordered erected in the fifties and sixties were called “Khrushobi” by the Russians. In 2010 approximately 85 percent of the housing was privately owned. I am not sure whether Masha was referring to Moscow or to all of Russia.

Our bus had to maneuver through bumper-to-bumper traffic at first, but then it cleared up. I saw some tiny buses that were jammed with people. No one explained them.When we passed a supermarket, the subject of Masha’s disquisition abruptly switched to groceries. Masha said that in Khrushcev’s time only canned fruit was available in winter. Now fresh fruit was in the stores all year long.

The outer ring road was built in the 1960’s. It was 109 kilometers in length. In many places the road corresponded to the city limits. On the stretch that we drove the north side was often undeveloped, while the right was always thickly inhabited. On the average Muscovites spend one hour commuting each way. I wondered how much the people taking the Metro brought down the average. We passed several Aushan supermarkets. I had seen their stores in Houston years ago. I later learned that this was a French company that had given up on the U.S. market.Moscow was founded in 1147. Siberia was conquered by Czar Ivan IV in the sixteenth century. There have never been enough people to work the mines there. There are some big cities there – Omsk, Tomsk, Irkutsk, Novosibirsk, and a few others. In 2010 Siberia was a popular spot for vacations. People enjoy Lake Baikal and other natural attractions.

As we entered the Yaroslavl highway, Masha predicted that a group of young men would be standing by the road. She was right. Actually, there were two groups. She explained that they were day laborers who had migrated to the Moscow area from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and other southern areas. Evidently there were lots of jobs in Moscow, but in the ’stans unemployment was high.The northeast highway on which we were traveling went all the way to Archangel, which is well on the other side of Yaroslavl.

We passed the town of Mytischi. The merchants from Yaroslavl had to stop there and pay taxes. In the twenty-first century it was famous for manufacturing the cars for the Metro trains.The town of Korolev was named after the designer of Sputnik. Space control for Russian flights, and a space museum were located in the town. We could see a rocket from the road. The cosmonauts, however, were not stationed there. They were trained in Star City, which is southwest of Moscow almost to Belarus.

Someone asked Masha about the new “Silicon Valley” that Mevedev has visualized. It is not in the Moscow area; it is in Skolkovo, which is well to the west of Moscow. I was happy to hear that they had decided not to put it in Moscow. Moscow did not need to attract more people.The bus driver, Victor, routinely – and vainly – changed lanes over and over. Some cars drove in the breakdown lane. The lane designations seemed completely optional; cars and trucks routinely straddled the lines.

Masha told us that a few years ago nice houses in the Moscow area cost $1 million to build. Their value had at least doubled.

Russians have long loved to harvest mushrooms. During the summer of 2010 there had been no rain and extreme heat. So, all of the vegetation was brown.In addition to the monastery Sergiev Posad was famous for its spas and sanatoria. Pilgrims journeyed there in hopes of healing their bodies and their souls.

St. Sergii of Radonzeh was a fourteenth century boyar. He left his home and moved with his brother to Sergiev Posad. Sergii built a shack and a chapel there. Eventually this grew into the monastery that we would be visiting. His brother left for Moscow. He also became a monk, but he did not like the isolation.

Sergii taught a large number of pupils. Many founded other mother monasteries. People from all over came to him for advice and cures.In 1380 Sergii persuaded Grand Prince Dimitri and other princes to join together to defeat the Mongols. This was the Russians’ first victory over the Mongols. Sergii asked two young monks to take up arms and enlist. One of them was the very first Russian engaged in the battle. It took Russia one hundred years to drive the Mongols out completely. Czar Ivan IV finally finished the job and annexed Siberia, which turned out to be a useful place for Russian rulers to have.

Russian Orthodox believer are supposed to visit the Holy Trinity Monastery at least once in their lives. Masha said that it was like the Vatican[3] in that respect.

Masha warned us that August 19 was a major religious holiday in Russia, the feast of the Transfiguration. She predicted that there might be big crowds at the monastery. In Russia the holiday was associated with the apple harvest. Nine churches and several palaces were on the grounds of the monastery.Stalin was expelled from the seminary in the third year of his studies. He allowed a religious procession in Moscow in World War II. Someone had a vision in which the Lady of Kazan[4] said that if some icon were carried around the city, Moscow would not fall to Hitler.[5] It evidently worked. They also took the icon to St. Petersburg and paraded it around during the siege.

We passed Abramtsevo, which was the home of many writers. It was founded by Sergei Aksakov as a colony for writers of the Slavophile school. Gogol, Turgenev, and others came to work there.

Our first stop in Sergiev Posad was at the toilets. We had to descend a staircase that was in very poor condition. In fact, one entire side of it was impassable. They charged to use the toilets. Those who needed to go pooled their coins together. The lady in charge evidently did not provide change.Masha told us that the tour of the monastery would last for one hour and would be led by a seminarian. She would translate for us from the Russian. After the tour we would have some free time and then would meet at 12:15 at the main gate. Then we would go to lunch together. We would depart at two o’clock.

A camera permit cost one hundred rubles. I bought one, but no one cared once we were inside the monastery. Maybe they relaxed their vigilance because of the holidays.The frescos in the gate depicted the young life of the saint. He was famous for once sharing his last piece of bread with a bear. The guide did not mention it, but Sergii seemed to look exactly the same when he was an old man as he looked when he founded the monastery.

The guide informed us that there were three hundred monks and novices in residence. The school associated with the monastery had an additional eight hundred students.

There was a notable presence of Russians on the monastery grounds, but the crowd was nothing like what one might expect on any day at Assisi or Lourdes. Most of them seemed to be rather elderly women, but there were also quite a few children. Almost all the women, including Masha, brought their own plastic bags. I noticed that the Russian women made a sign of cross whenever they passed a church or the statue of St. Sergii. Their gesture was very deep – much lower than Roman Catholics did it – and they went to the right shoulder first. The bell tower was eighty-eight meters high. The “Good News” bell started ringing almost immediately upon our arrival. It weighed thirty-six tons. The biggest bell weighed seventy-two tons. Its tongue alone weighed eight tons. Three thousand people dragged it to the monastery from where it had been made.The services in the Russian Orthodox church supposedly lasted for about four hours. There was a morning service and an evening service. No one ever used the word “mass.”

The Assumption Cathedral had been built in the sixteenth century. The outer wall of the church failed when a spring was opened. The wall was undermined. A one-eyed monk splashed some water on his eye, and he was cured.[6]

The pink chapel was baroque. Next to it was a gazebo in which holy water was dispensed from a fountain. This seemed to be a major attraction. People splashed it on themselves, drank it, and took jugs of it home. The necropolis beside the cathedral contained the remains of Boris Godunov. No one seemed to pay any attention to it.It took thirty-five painters one summer to restore the Assumption Cathedral. Czar Peter I came here twice and donated the chandeliers. One was bronze and weighed two tons. The other was copper and weighed less than one ton.

The two mosaic icons were discovered in the Kazan Railroad station. They were not identified for fifty years. The coffin of St. Sergii was on display.The old refectory had been converted into a big (by Russian standards) church. Huge feasts were formerly held there. The czars and their families were often pilgrims. The refectory was closed during the Soviet days and severely damaged. Two small altars had recently been installed. We went inside and hung around in the vestibule for a while. We were told that the anteroom was for those who had not been baptized and for serious sinners seeking forgiveness. In answer to a question, the guide said that the Russian Orthodox Church does have the sacrament of confession. In the vestibule people were studiously filling out written petitions and lighting candles. This was never explained.

A service was in process when we entered. I could hardly believe that tourists were allowed to mill around while the priests were distributing communion, which consisted of a rather substantial bun and a small cup of wine. I got weirded out and hurried outside almost immediately. It was Notre Dame all over again or even worse. In that case the building was owned and operated by the state. In this case our guide was actually a seminarian himself. The Russian Orthodox Church has never had cardinals, but when the last Patriarch of Moscow died in 2008, a new one was selected by some group that was never explained to us. In the last election there were three candidates. One of them withdrew. Kirill was elected to succeed Alexy II. There are two types of priests in the Russian Orthodox Church. “Black priests” are monks who take a vow of celibacy. “White priests” are parish priests who do not take the vow and must, in fact, get married. Someone asked how the priests found women to marry. The guide answered that the icon-painting department and the choir directors in the adjoining school are mostly female. There was a perpetual service in the Cathedral[7] of the Holy Trinity, built on the site of Sergii’s shack. No photos were allowed within. We saw the very long line to venerate St. Sergii’s corpse, which was encased in a silver shrine. I may have been mistaken, but I thought that I saw the head tour guide Andrei in line. Sergii’s corpse has allegedly not deteriorated since he was buried in the 1400’s. Ivan IV financed the building of the cathedral. Much later Empress Anna supplied the silver. Andrei Rublev’s “Trinity” icon was originally created for this church. Three of the five rows of the iconostasis survived the desecration by the Communists.I saw a kid wearing a tee shirt with “American Golfing Championship” on the front. I have long wondered where all of these phony tee shirts worn by European youngsters come from. Do the young people who wear them think that someone in the United States would ever wear something like that? Why would anyone want to imitate American fashion anyway?

We all paraded over to the Russki Dvorik (Russian Yard) restaurant. It was across the street from the monastery. All of the people from bus #42 were seated in the main room. Two tables in that room were also provided for the people from our bus. The rest of us were escorted to a separate room. This was a lucky break; the big room was hot and noisy. The only people whom I knew at our table were the Frases from Arkansas. Most of the others seemed to be Canadians. We started with a salad of tomatoes and cucumbers (not my favorite) with oil and basil. The soup was mushroom and noodles. It looked and tasted like Campbell’s. The main course was fish of some kind, peas, and potatoes. Dessert was ice cream. The service in the restaurant was peculiar. Despite the fact that there was plenty of room, the waitresses refused to go behind us. Instead, they made us pass food down to the end of the table and pass the dirty dishes back. The other weird thing was that they only filled the coffee cups halfway. The water was served in dark blue Русский Дворик bottles. I stole one. One guy at our table ordered a beer that cost two hundred rubles. That was almost as much as Tom paid in Mandrogi, but the glass was pretty large.

Someone mentioned that the tap water in the hotel in which they stayed in St. Petersburg had been brown. I remarked that at least they did not need to warn the guests not to drink it. Maybe it was fortunate that Patti, Tom, Sue and I discarded our original idea of staying in hotels.

Evidently I missed the guides’ marching orders during my sojourn to the restaurant’s men’s room. Some people started wandering back toward the main gate, and others lingered around the restaurant looking for souvenirs. I did not know what we were supposed to do. I finally walked back to the monastery by myself and just tooled around outside for what seemed like hours. At one point it drizzled very lightly for a few minutes. I took shelter under a tree, but it was never serious enough to impel me to take out my umbrella.

A young man accosted me while I was standing around and asked where I was from. I told him. He wanted to trade Russian coins for American coins. He held out his hand and showed me some coins. His looked like kopecks to me. I told him that I did not have any coins, which was true unless you counted what I had stashed in my backpack before our first flight.I hung around near the shops, all the while making sure that I maintained visual contact with someone from our bus. We finally were ready to leave about two, but Susan and Elizabeth McCord were missing. I had seen them just a few minutes earlier, but they had disappeared in the interim. We departed when they finally showed up.

On the bus ride back to the ship Masha told us that the czars often walked from the Kremlin to the monastery in pilgrimage. Alexei Romanov, the father of Peter I, built a church at some point along the route. Masha asked if anyone had any questions. I asked about the Cathedral of the Assumption. My first question was whether people in Russia really believed in the Assumption, since it was not in the Bible. At first she thought that I did not know what the Assumption was. She said that I might know it as the Dormition, a term that is almost unknown in the west. I reiterated that the Assumption was not mentioned in the Bible. She consulted with Polina and Victor in Russian and then said that it was in the ancient books.Well, maybe they were ancient by Russian standards, but there is no mention of it at all before the sixth century, which is more than five hundred years after the alleged event. Furthermore, it is not in any version of the creed. It was not added to the Roman canon until the twentieth century. I decided not to press the issue since it was obvious that no one else cared.

I then asked when the Assumption was celebrated. I was surprised that no one seemed to know. Masha finally said that it was probably about eleven days after the western feast day. This turned out to be close. It was celebrated on August 28, which was only nine days after the Transfiguration holiday. It surprised me that two important holidays were so close together. The capital of Russia has not always been in Moscow. The first capital was Kiev. Then it was moved to Vladimir. From there it went to Moscow. Peter the Great moved it to St. Petersburg. The Bolsheviks move it back to Moscow.We passed another town named Pushkin. This one was an industrial center in 2010. It was given to Alexander Pushkin’s ancestor.

Masha explained the Russian approach to maternity. Pregnant women get paid leave for the two months before and the two months after birth. Their jobs are protected for three years if they decide to stay home. Kindergartens and day care are of high quality. The children are taught reading, numbers, and “how to rappel.”[8]It rained a little on the way home. Our bus had one huge windshield wiper. There was a horrendous traffic jam on the MKAD. We stumbled along in first gear for over an hour. It cleared up when we finally passed one of the spoke roads. It took us two and a half hours to get back to the ship. There was absolutely no problem on the road on which we were traveling. The entrance onto one of the crossing roads was just backed up. This was not during the rush hour; it was early afternoon. I honestly did not understand how anyone could stand to live in a place where the traffic was this bad.The town of Khimki was just on other side of the MKAD on the Leningrad Highway. It used to be famous for its defense industry. In 2010 it was more renowned for its IKEA store.

Masha said that in May there had been a “traffic collapse” on the Leningrad Highway. As bad as it was in August, I could not imagine what a collapse could have been like. I did not enjoy this tour at all. I learned almost nothing about the orthodox religion, and there was not that much to see in Sergiev Posad. The young man who guided us added very little to the experience. The fact that Masha had to translate everything that he said was tiresome. The lunch was OK, but it seemed rather pedestrian, unimaginative, and touristy. The worst part, of course, was the drive. It probably would have been more tolerable if I had had someone to converse with or if I had brought my computer with me or if we had sung “One Hundred Bottles of Vodka on the Wall.” I never dreamed that I had signed up for four hours of sitting in the bus by myself. As soon as I got back to the ship, I took a shower and then asked Sue if she wanted to get a beer or two. I inquired as to how she and the Corcorans had spent the day. I learned that Tom went on the excursion to the Military Museum in the morning, but Sue and Patti did not. The three of them had planned on taking the Metro into town in the afternoon. Patti and Tom went, but Sue decided not to join them. She accompanied them as far as the nearby Metro station, but at the last minute she decided that she preferred just to explore the park rather than deal with the stairs and walking. I told Sue that I did not like Sergiev Posad and that the traffic was unbearable. Romeo, the bar attendant, brought us lots of chips, peanuts, and olives to consume with our beers. He seemed lonely. Tom and Patti returned from their adventure in the city and joined us for supper at 7:30. I had the Salad Nizzi, which was tuna and haricots (whatever they are), vegetable bouillon, halibut with peas puree, roasted potatoes, and beetroot sauce, orange cream with chocolate sauce. All the other choices were better: chicken salad, mushroom soup with thyme croutons, reindeer ragout (I gave Sue my cherry tomato for the red nose), and ice cup “Red Square.”Tom thought that the tour of the Military Museum was great. He told us about Russian women pilots in wooden airplanes who dropped bombs by hand at night. The Germans thought that they were witches. He said that there was a lot of other interesting stuff there, too. I definitely made the wrong choices all day long.

Tom and Patti had quite an adventure on the Metro, as well. They managed to use it successfully, but they had a tough time dealing with the Cyrillic letters on the signs. They were very impressed with the Arabat shopping district.Tom continued to rave about the quality of the Russian ice cream.

We had one more day of touring in Russia. It almost certainly was bound to be better than this one, which was the nadir or the tour for me.

I went to bed. Tom, Sue, and Patti went on the Moscow by Night tour.

[1] I read on the Internet that from 1946 to 1983 Sergiev Posad was indeed the seat of the Patriarch of Moscow.

[2] My calculation may have been flawed. The grades of gasoline did not seem to match up with the ones with which we were familiar.

[3] Masha must have been confused. Roman Catholics have no obligations to undertake pilgrimages. She may have been thinking of the Muslim requirement of the Hajj.

[4] According to OrthodoxWiki on the Internet, the “Lady of Kazan” is itself an icon, and it was definitely not in the country during World War II. I must have misunderstood.

[5] I could find nothing about this on the Internet.

[6] I wonder if they tried this on Marshal Kutuzov.

[7] How can there be so many cathedrals? A cathedral is by definition the seat of a bishop. Either the Russians must have had bishops who shared bunk beds or perhaps the Russian word собор does not exactly mean “cathedral.”

[8] I could swear that that was what she said. I have no idea what she meant.