After the briefing I retreated to a chair on the deck to work on the journal. At some point the Surkov had left the Volga River and entered the Moscow Canal. On either side there were now visible very nice dachas (or maybe houses), boats galore, and lots of swimmers. I also saw a park.

Susan McCord power-walked past me twice. A gentleman also was walking laps around the deck. I worried about him at first; he seemed to have a lot of trouble breathing. However, he must have adjusted, for he seemed to wheeze less with each succeeding passing.

At eleven I went back up to the Sky Bar for a round table[1] discussion by the six tour guides. Andrei, who was the head guide, ran the discussion, which was really a question and answer session. He said that 191 passenger were on our cruise. Andrei Surkov, for whom the ship had been christened, was a poet and journalist. Some of his poems became songs that were hits during World War II, which was known in Russia as the Patriotic War. Surkov’s works were especially popular in the front lines.Tatiana was asked to explain a term that she had used: “Political vertical.” She explained that the Russian President appointed all of the local governors. The President’s main job was to “guarantee the constitution.” He could veto any bill that the legislature had passed. I would guarantee the constitution, too, if it gave me that much power. How in the world was an opposition supposed to get any traction if everyone with any authority was appointed by the president?

Galina said that she had visited eighteen countries.In the Soviet times there was no unemployment whatever. In 2010 there were plenty of jobs in Moscow, but the outlook was not so rosy in the other towns and cities. Nevertheless, all of the guides seemed to agree that life in Russia was much better than in the nineties.

Someone asked what made each of them the most proud concerning Russia. Polina said that she was proud of the resurgence of the orthodox religion. She said that the religion was very strict. For example, people were asked to fast two-hundred twenty days per year. She said that about 12 percent of Russians followed all of the rules, but a lot more attended services. In what she called “the bedroom communities” the people could hardly squeeze into the churches on Sundays. In some services the priest preached in Church Slavonic,[2] and it was translated into Russian.

The current Patriarch of Moscow was named Kyril. Andrei said that he encouraged the government to help the poor. 11 percent of the country was Muslim, but most of them live in the south. Russia still had free health care, sort of. Some people spent extra to get better care. There was “compulsory insurance” and “voluntary insurance.” This exchange was educational but a little frustrating, too. I definitely got the impression that the tour guides were expected to put a positive spin on nearly everything. There was no disagreement whatever. If the same kind of thing were done in the U.S., you would not be able to find six people who could stay in agreement for an entire hour.I had hoped to ask about who controlled the media in Russia. I wished that I had been assertive enough to open my mouth. No one ever broached the subject in all of the time that we were in the country. I suspected that the government still controlled at least the broadcast media, but I could be wrong.

For lunch the restaurant served Swedish meatballs, pumpkin soup, and pork necks marinated in beer. Tom naturally ordered the pork necks. He and his son Brian have always gone for every type of weird food that they encountered. I skipped dessert, as usual.

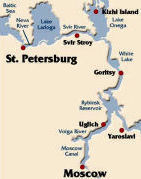

We landed in Moscow just as lunch was ending and docked next to a ship with a disarmingly similar name to ours: Vasily Surikov. I learned that its namesake was a very famous Russian artist of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century whose paintings were featured at the Tretyakov Gallery. We had to pass through Vasily’s ship to get to the dock where the buses were parked. For our tour of Moscow our driver was Gennady (not the Viking tour guide) and our local guide was Tatiana (also not the Viking tour guide). Tatiana had a very melodious voice.Our ship was docked near the last Metro station on the green line. Tatiana said that it was a pleasant fifteen-minute walk to the Metro station from the pier.

The total distance that the ship had traveled was approximately two thousand kilometers. By road it would have been only seven hundred kilometers, an easy day’s drive. Everyone in Moscow lived in apartments. This statement was almost literally true. We saw no houses within the city limits. In 2010 every third family in Moscow owned a car.[3] People started work at different times. The office workers did not start until ten. In 2010 seven million people took the Metro, which cost twenty-six rubles, every day. It was unclear to me whether that was that seven million trips or seven million different passengers. The worst day for traffic was Friday. A very large number of Muscovites wanted to drive to their dachas for the weekend without going back to their flats. There were numerous parks in Moscow. The high temperature forecast for Wednesday would be about 95 degrees Fahrenheit or 35 Centigrade.The city of Moscow was divided into thirty-two districts and numerous minor districts. School would start on September 1. Moscow had no school buses! Everyone walked to school.

Most cars in Moscow were foreign-made. They were more expensive than Russian cars, but people found them more reliable. That sounded familiar. Parking was a horrendous problem. There were very few parking garages. Plenty of people just parked on the sidewalks. I saw no parking meters and very few “No Parking” signs.Our bus proceeded down the Leningrad highway and passed through the Sokol (falcon) district. It seemed hard to believe that this part of the city was once used for hunting.

We passed the Dinamo stadium. It occurred to me that I probably could purchase a soccer jersey there if I had time and could figure out how to get there. There were nine railway terminals in Moscow, four or five airports (depending on what you were willing to call an airport), and, of course, the river port. I later learned that Russia’s three largest airports were all in Moscow.After a few miles the Leningrad Highway became Tverskaya St. It got even busier at that point, but because it was wider, the traffic actually flowed a little more smoothly.

We passed a statue of Yuri, the founder of Moscow, mounted on a horse. I took a photo of it from the bus, but it was quite blurry.

The photo that I snapped of the KGB building was of much better quality. Tatiana told us that twenty years ago there was a statue of Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky in front of it. After the Communists lost power, the statue was pulled down.[4]

From that location we could see from the bridge through the haze the outline of the huge maritime statue to Peter I. It was designed and executed by Zurab Tsereteli. Not for the first time we heard that Peter the Great had implemented the first professional army and navy in Russia.

The Cathedral of Christ the Savior boasted the largest dome in the city. Five onion-shaped domes were supposed to represent Jesus and the four evangelists. Well, maybe. The building was demolished by the Bolsheviks and rebuilt in 1990[6] by the Russian Orthodox Church with funds from private donations It could hold ten thousand people at a time. Gold dust had been attached to the dome using x-rays. Tatiana confirmed that all of the churches in Russia were packed on holidays.The bus drove past the Pushkin Museum of Fine Art. I did not write any notes about it other than that it held non-Russian works.

We passed a statue of Friedrich Engels that somehow never got pulled down. I thought that I had been unable to get a good photo of it from the bus, but one of them turned out pretty well.

Denis Davydov, a poet and a popular hero of the War of 1812 against Napoleon, had a monument near his grave site. Moscow had a circular street around the center of the city called the Garden Belt. Tatiana told us that it was twelve kilometers in circumference.Tatiana pointed out the Tolstoy House as we passed near it. Tolstoy initiated schools in the villages. He was a simple man who wanted to give away his money, but his wife and ten children had other ideas. He was buried in his family’s estate.

It must have taken us ten or fifteen minutes to circumnavigate the New Maidens Nunnery. Unfortunately, it was on our right for the entire journey, and I was sitting on the left side of the bus. I did not even attempt a photo. Peter I sent his first wife, Eudoxia, and his half-sister, Sophia, there. Tatiana told us that the belfry was always situated next to the church to drive away demons, which reportedly did not care for the sound of bells. Many famous people had been interred in the cemetery of the New Maidens Nunnery, including Raisa Gorbachev, Boris Yeltsin, and Anton Chekhov. Thirty nuns currently lived within the walls of the convent. Russian Orthodox nuns abstained from all meat. A special pond was installed to provide them with fish. Tatiana told us that cruising the Moscow River and the canals was popular with locals. We passed the Cathedral of Our Lady of Smolensk, which was within the confines of the convent. It also had five domes.Tatiana then pointed out a very large sports complex with a ski jump. She did not call it the Olympic Stadium, but that was in fact its name. I took a lot of photographs of it from the bus. This turned out to be a silly waste of time and effort. We were soon to park the bus in a spot with an excellent view of it. In front of the stadium there was a pool that was used for international competitions.

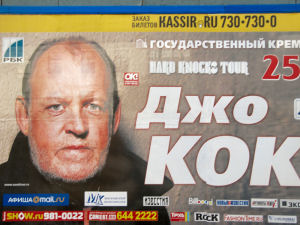

We saw lots of construction literally all over Moscow. There was no doubt that this city was bustling and growing. There was no telling where they would put them all.I saw signs advertising upcoming concerts by both Joe Cocker and Leonard Cohen. Their names were spelled in Russian. I doubted that most members of the tour noticed them.

We entered the southwest district of Moscow. For some reason Tatiana gave us statistics on this area. It was home to one million people. Moscow State University was in the district. It boasted thirty thousand students, of which approximately one thousand were foreigners. The spire on the top of the building with a star was a remnant of Stalin’s era.

Newlyweds were every bit as much in evidence in Moscow as they had been in St. Petersburg. Polina later told us that all of the couples first “register” with the state as husband and wife. Most of them then participate in a religious ceremony even if they don’t believe.Just before we made a comfort stop, Tatiana informed us that birch trees were the most common variety in Russia. This certainly accorded with what we had observed from the ship and various buses. Before we descended from the bus Polina warned us that the restrooms had “Asian style toilets,” which was a polite way of describing them as holes in the ground. I did not feel the need. Afterwards I told Sue that she should have taken a photo of the facilities for my journal. She replied that someone was indeed taking pictures in the ladies’ area.

While others were relieving themselves I rushed up to try to photograph the university building. I found a pretty good place for a shot, but the haze obscured it, and I was in too much of a hurry to do a good job. As it turned out, it mattered not a whit.After we piled back on the bus, Gennady surprised me by maneuvering the bus up a hundred yards or so to the corner on which I had taken the picture of the university. He then executed a U-turn and brought the bus to a stop directly across the street from where it had been parked a minute or two earlier. Because of the congestion caused by other buses at the site Gennady could not exactly park. He guided the bus within six or eight feet of the sidewalk, decided that that was close enough, and let us out. The driver of the trolley that came up behind our bus did not agree with his decision and dramatically made his opinion known by means of his horn.

Unfazed, the bus #45 group trooped up to the nearby overlook. The “Panorama” view that Tatiana had touted was actually not very good because of the haze. I was, however, able to get a little better picture of Moscow State University in the other direction. A great many vendors had tables at the viewing point. They featured the most exhaustive selection of souvenirs that I had seen, although I would readily admit that I did not look very closely at the offerings here or elsewhere. A few of the tables featured the military hats that I admired, but no one had one in my size. One incredibly gigantic one was size 61. It might have been appropriate for Andre the Giant. The next largest size was a 56, which was much too small for me. If I had to guess without measuring, I would say that I needed a 59 or 60. The Moscow Metro was built in 1937. In 2010 it boasted more than three hundred stations. Most of the stations were made of marble. The tracks were so deep beneath the ground that some of the stations served as bomb shelters during World War II. All of the stations were well lit and ventilated. They were not heated, but they remained fairly warm throughout the winter and cool in the summer because of the air pressure.[7] Tatiana assured us that the stations were quite clean even though there were no trash cans. No smoking was allowed in the Metro. Drunks likewise were strictly prohibited. Tatiana disclosed that there were lots of heavy smokers in Moscow. Frankly, if I had to live there, I would also probably seek out some chemical assistance. Adding more smoke within and without my body, however, would not have been my likely reaction.Fun facts: Before 1917 Moscow had been a textile center; it was known as “Calico City.” The glass pedestrian bridge was formerly a railroad bridge. The “White House” was originally the home of the Parliament; this was the building that Yeltsin ordered to be shelled. Tatiana mistakenly identified the Ukraine hotel as a Marriott; actually it was a Radisson. That gigantic structure was one of Stalin’s Seven Sisters.

The bus passed one of the inevitable monuments to World War II volunteers.I wrote that apartments in Moscow cost between $5,000 and $7,000 per square foot, but I think that Tantiana actually said per square meter. Almost all of them were purchased. Hardly anyone rented.

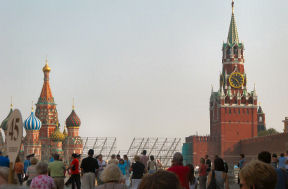

Most of our group boarded the Metro at Park Pobedy (Парк Победы: Victory Park) station. Sue did not want to deal with the stairs; she stayed on the bus. The people who remained on the bus would meet the rest of us at Red Square. We descended about twenty stairs and then went down a very long escalator. We inspected a painting[8] at one end of the long hall of the leaders who had defeated Napoleion in what Russians called the Great Patriotic War. Marshal Kutuzov, the one in the light blue coat, had lost an eye, so he was always shown in profile. The trains in the Moscow Metro traveled at approximately fifty kilometers per hour. One arrived every thirty to forty seconds during the rush hour. Even when we were there, the wait was no more than two minutes. All of the large cities in Russia – St. Petersburg, Tashkent, etc. – had underground Metros. In the one in St. Petersburg a special arrangement of gates helped to protect against flooding. Our group got off at the fourth[9] stop, Revolution Plaza. This Metro station appeared to be contiguous to one named after Lenin. Between the exit into Revolution Plaza and the entrance to Red Square we saw a statue dedicated to Marshal Zhukoff. The “Red” in Red Square does not refer to the color. The old Russian word красная originally meant “beautiful.” Lenin’s tomb was only open from ten until one, and it did not open at all on Monday or Friday. We were in Red Square on Wednesday, but the Surkov had not even docked by one. We were not allowed within fifty yards of the building.St. Basil’s Cathedral,[10] which was at the far end of Red Square, was constructed at the direction of Ivan IV. Tatiana said that the czar blinded its architect, Postnik Yakovlev, when he boasted that he could produce another of equal beauty. It was dedicated to the people who helped drive out the Mongols. There was also a monument to Minin and Pozharsky, who led the fight to rid Russia of the first False Dimitri in 1613 and saved the country from brutal subjugation by the ruthless and warlike Poles.

When parades were held in Red Square, the government officials stood on the level over Lenin’s name to review the troops. Cobblestones were used to pave Red Square because the Soviets liked to drive their tanks in it. Their treads would have torn up anything else.The long brick wall of the Kremlin with its huge towers formed one border of Red Square. The Communist rulers were buried at the foot of the Kremlin’s wall. Plaques have been dedicated nearby to Gagarin, Zhukov, and many others. Tatiana noted that “They say that two million Russians visit Moscow every year.”

We could see one clock tower of the Kremlin. The star on the top was ruby-red. It was the official clock for the New Year’s eve celebration in Moscow.

It was obvious that they were in the process of constructing a stage in Red Square. Tatiana did not know what the occasion was. Part of the square was reportedly used as an ice rink in winter. GUM, which was across the square from the Kremlin, was built in 1893. In the Soviet days it was a true department store. Now it is more like a mall with lots of ritzy retailers, most of them from western Europe. On all three floors there were three lines of stores with two very long hallways separating them. The fountain in the middle served as our point of reference. Tatiana led us up to the bathrooms on the third floor. Then she told us where the bus would be and let us explore on our own.

I have never enjoyed shopping, and I generally avoid malls like the plague. I took some photos of some autos that were on display, and then I decided to walk to the far end of the building and exit from there. Tatiana said that there was a shop that sold sports clothes on the first floor at the far end. I found it, but there was nothing there but gear festooned with the logo of the Russian Olympic team. Honestly; they sold nothing else.

I took photos of St. Basil’s from just about every imaginable angle. There was a miscommunication concerning how much free time we had to explore the square. The time that Tatiana advised us to meet was thirty minutes earlier than the time that Polina prescribed for those who eschewed the Metro. I ran into Sue outside of GUM, and she knew the right time. She insisted that I take a photo of her in front of a cafe with an orange awning, because the color was the same as one of the stripes on her poncho. I also took a photo of Sue and Patti wearing their surgical masks with St. Basil’s in the background.

I ran into Tom, and I followed him to the area in which the bus was parked. That was a mistake. He got on bus #43, and I was right behind him. The people already seated there hooted us off when they saw the 45 on our receivers.

We found our way over to the correct bus. The fellow seated in front of me had purchased a can of “Hooper’s Super Hooch.” Its label said that it was 9 percent alcohol flavored with grapefruit juice. I had considered buying a Diet Pepsi from a vendor near the buses, but I decided to stick to water. Most of us consumed our box lunches on the bus. It contained the same awful sandwich as the lunch that we had in St. Petersburg. It also had bacon-flavored chips, a granola bar, a very bitter apple, and some water that was especially welcome. This time I avoided the sandwich entirely. I was not about to complain. This was our third of four meals today, and it was not as if any of us were on the verge of starvation when we woke up this morning.

We then drove to the House of Scientists for a concert by a group named Moskva (mahsk VAH), which is what Russians call their capital city. The performers were graduates of the Moscow Conservatory. The conductor was their teacher. The orchestra members played traditional Russian instruments. The domras were on the left, and the balalaikas were on the right. For some reason all of the domra players were women, and all of the balalaika players were men. The lady playing the gusli, a couple of guys playing the very complicated accordions known as bayan, and a couple of flutes were in the middle. There were also two percussionists.

My attention was drawn to the balalaika player on the far right. He must have been in on a joke that no one else knew. Several times he got a big grin on his face when everyone else looked serious.

Everything they played was enjoyable. In addition to the orchestral numbers there were several solo performances. The first was a guy playing the balalaika so fast that his hands were literally impossible to photograph. Then a young lady in a gown sang Musetta’s Waltz from La bohème[11] and another aria that I had heard but could not place. She later sang a Russian folk song. Two ladies played a duet on the domra. The bayan player was an amazing virtuoso. One of the percussionists livened things up with a terrific performance on the vibes. The guy who stole the show was a bald guy who played a saw and an array of other instruments while he was dancing around and hamming it up.

I think that just about everyone had a good time at the concert. If not, the problem was probably the heat. Even I found it rather hot in the theater, which, like just about everyplace in Moscow, lacked air conditioning.

When we left the theater at a little before nine, it seemed very weird that it was still light out. I was even able to take a few pictures from the bus on the way back to the ship.

The restaurant served supper at 9:30, and it did not skimp on it either. The choice of appetizer was the chef salad, which was mixed greens, tomato, cucumber, ham, and cheese or a tomato stuffed with Russian cheese salad. For soup I chose the Solianka “Moskow” over the bizarre bell-pepper orange soup with sour cream. Sue chose the Swiss style sautéed slices of veal served with potato Roesti and asparagus and regretted it. I thought that the Golupsi, white cabbage stuffed with minced meat served on potato Mouseline and tomato sauce, was pretty good. Dessert was banana bread pudding with chocolate sauce or ice cup amaretto with amarettini. I skipped dessert and went to bed.

The first day in Moscow was exhausting. I found the bus tour disappointing. Moscow does not really have a skyline. The haze spoiled most of the photographs. Nothing stood out as extraordinary except, of course, for the Metro and St. Basil’s. I felt sure that if we had started in Moscow I would have been more impressed. We still had two full days to get to know the city.

[1] Actually, there were three round tables in front of them.

[2] Could this possibly be correct? Even in the days before Vatican II in the Catholic churches, when the rest of the Mass was celebrated in Latin, the sermon was always given in the local language.

[3] Polina later told us that most Muscovites have cars, and a good percentage of them have more than one.

[4] Of course the passive voice was used here. In 2010 Russia’s “unpredictable history” had not yet decided who had actually performed that act.

[5] I wonder if this is where Federico Moccia got the idea of having the couple in his best-selling romantic novel Ho Voglia di Te place a bicycle lock on the Ponte Milvio.

[6] It was started by a different architect, but the final work was the brainchild of Zurab Tsereteli, the same artist who did the statue of Peter I.