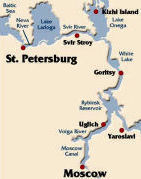

Most of the touristy attractions of Uglich were concentrated in the Kremlin, an area that was within walking distance of the ship but separated from it by water. To reach it the entire group – and all of the other groups – turned right at the town hall and crossed a bridge that spanned a moat.

The last war in Uglich had been in the seventeenth century, presumably in the Time of Troubles. Those nasty belligerent Poles burnt down the town. Despite the fact that Uglich was only about two hundred miles from Moscow, it survived World War II untouched.I took no photos of the interior of the churches in Uglich. I do not remember whether photography was prohibited or not. If they charged for the right to take photos, I evidently was feeling cheap that day. Fortunately, Sue bought a book that included some of the most interesting frescoes and icons.

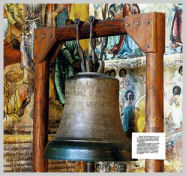

Alexander showed us the fresco[1] that depicted the Uglich version of the events of the fateful day of May 15, 1591, on which an eight-year old boy named Dimitri[2] died. He was the son of Tsar Ivan the Terrible, who had died a few years earlier. Russia at the time was ruled by Ivan’s other feeble-minded son, Fyodor. Fyodor was strongly under the influence of his brother-in-law, Boris Godunov, who had absolutely no blood ties to the Rurik dynasty, but still had his eyes on the prize. Dimitri was not legally in line to become the czar because his mother was Ivan’s seventh (!)[3] wife. By Russian law Dimitri was illegitimate. Of course, he still had better credentials than Boris Godunov, who was a Tatar. The official version of the story promulgated by a government commission held that Dimitri, a youth with no claim whatever to the Russian throne, was playing mumbley peg. He had a fit and accidentally stabbed himself in the neck. Dimitri’s mother and her friends then incited the local citizens by blaming the event on some of the czar’s representatives. The people rioted and stoned the czar’s men and a dozen other people who certainly were not involved in the incident. The story that held sway in Uglich was materially different. In it Ivan’s will called for the infant Tsarevich Dimitri, his mother, and their retinue to go to Uglich “to rule.” Seven years later Boris Godunov sent his assassins out to find the prince. They located him in Uglich, managed to separate him from his relatives and servants, and accosted him. They then complimented the youngster on his “new necklace.” He replied that, shucks, it was old. They then gave him a brand new red one by slitting his throat. An invisible person[4] – almost certainly an angel – then roused the citizens of Uglich, and rang the bells. They all rushed forth and dealt with the assassins in accordance with their obvious civic duty. Everyone agreed about what happened next. Dimitri’s mother was shipped off to a convent. All of her relatives and supporters – hundreds or even thousands of them – were either killed or exiled to Siberia. Alexander told us that even the bell that had roused the citizenry was sent into exile, but only after it had been flogged, and its tongue had been removed. Boris Godunov eventually did succeed Czar Fyodor. Dimitri was declared a saint, but not until the Romanov dynasty was well established. Andrei Rublyov, the famous iconist whose work is featured in the Tretyakov gallery, painted some of the frescoes in Uglich.A rumor circulated that Tsarevich Dimitri had not died after all. Alexander reported that there were as many as seven false Dimitris who came during the Time of Troubles and laid claim to the throne of Russia. The first Dimitri came from Poland and actually ruled as czar for about a year.

Tsarevich Dimitri was buried in a cathedral in Moscow. He is shown with his knife on the flag of Uglich and on just about anything else imaginable that is associated with the town.

In the Cathedral of the Transfiguration a group consisting of five guys known as The Ark sang a sacred song and “Down the Volga River.” They sounded very good, but so did all of the other choirs that we had heard. When the concert ended, we were hustled out a side door, and I stupidly left my backpack behind. Polina had to retrieve it for me.Alexander explained that the Volga became wide and powerful south of Moscow. That accounted for the almost uncomfortable dynamics employed by the singers in some portions of the second number.

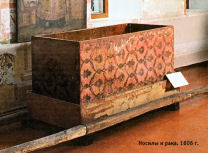

We visited the beautiful Church of St. Dimitri on the Blood. The edge of Uglich also boasted a second Church of St. Dimitri. That one was called “In the Field.” The one that we visited had an iron floor designed to radiate heat. The frescoes were from the eighteenth century. The famous bell that sounded the death knell for Tsarevich Dimitri was brought back to Uglich in 1892.

The Cathedral of the Transfiguration had green domes. Its design was called “Russian Classical.” Alexander told us that Raphael’s famous painting of the transfiguration from the Vatican had been copied for this church. The icons from the nineteenth century belonged to the previous church.

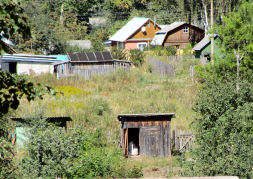

After Alexander completed his tour, we were allotted quite a bit of time to explore Uglich on our own. Patti and Sue wanted to try on the traditional Russian costumes and to have their photos taken on the portico of the palace. I certainly should have stayed with them long enough to take a few photos of them posing in their rented regal outfits, but I had absolutely no interest in that activity at all. By that time I was beginning to get antsy, and my experience was that this kind of thing always seemed to use up a lot of time.For some reason Alexander’s little tour really left me cold. That the city seemed to base its whole existence on this bizarre event over four hundred years ago seemed very silly to me. The churches were not real; they were all redone for the tourists, and I was frankly sick of tourism at that point. We had not really dealt with any Russians on their own terms on the entire trip. We only saw what they wanted us to see. I was eager to discover what life in Uglich was really like. So, I took off on my own and wandered around the town by myself for an hour or so.

I cannot report that I made a lot of startling discoveries. I saw some really dilapidated houses and a few pretty nice ones. I saw some old shoddy apartment houses and one new one. I saw churches that were still closed while they were allegedly being restored, but no one seemed to be working on them. I saw a kindergarten, a convenience store, a flower shop, and an extremely unlikely looking bank.

I happened upon the parking lot in which the taxi drivers congregated when they were not busy. I wondered to myself why Uglich needed any taxi drivers at all. It appeared possible to me to walk from one end of the city to the other within ten or fifteen minutes. From the map there appeared to be only one hotel. Even Enfield, CT, which was about the same size, had four major hotels in 2010.

I wondered what the people here did for a living. My understanding was that the watch factory had closed down. What had replaced it? A pretty large portion of the locals appeared to be engaged in tourism, but surely satisfying the western craving for nesting dolls was not sufficient to support a town of forty thousand, was it? And what did everyone do during the winter?

I saw much less traffic in Uglich than in Yaroslavl. Furthermore, a much higher percentage of the cars appeared to be old or in marginal condition. Even the taxis looked a little shabby. My impression was that Uglich was not doing very well.

Uglich was just downstream from Moscow, which was evidently the source of all wealth in Russia. I wonder what things were like when one got out into “the provinces.”

One habit that I definitely noticed was that the people of Uglich – or at least the female ones – always seemed to carry a plastic bag with them. I had read that Russian shops would willingly wrap purchases, but they often did not provide bags. People in Russia customarily brought their own bags. My impression was that this custom had disappeared in the cities like St. Petersburg and Yaroslavl, but it might still be prevalent in the smaller cities and towns.I discovered that a rather large park was adjacent to the pier. It was not actually necessary to run the gauntlet of tourist vendors in order to return to the boat. I rested my legs in the peaceful park for a while and watched a couple of young people pretending to rake leaves there. I discovered some very weird things in and around the park. There was a small vodka museum within one hundred yards of where the ship was docked. I was surprised to see a sign on the door – in Russian – that indicated that the museum opened at 11:00. The passengers on the Surkov were on notice that they had to be back on board by 11:45. I felt quite certain that none of them visited the museum. In fact, they probably did not even know it existed. A little ways up the street from the museum was a shoe store. Two things about it caught my notice. Whereas the museum and seveal nearby stores were across the street from the park, the shoe store was actually in the park. At least, it was surrounded on three sides by the park. I could not imagine how that could happen. The other peculiar thing was that the store had no shoes on display. If I had not had my dictionary with me, I would not have known what they were selling. What to conclude about Uglich? This was the most difficult part of the journal to write. My notes from the tour were very sketchy. I was not even certain whether we went into two churches in the Kremlin or three. Maybe I got flustered when I discovered that I had left my backpack behind. Again!

My walk around Uglich was also dissatisfying. I longed to see something startling that would bring home to me the nature of life here. Instead I saw a little of this and a little of that. Russia was still “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma” to me.

For lunch the restaurant on the ship served what they called “German sausage” and sauerkraut. It looked like knockwurst to me. I had the carrot-ginger soup with sesame seeds and the chicken Kiev with carrots, rice, and peas. I skipped the Penne rigotta (whatever that was) with mushroom sauce and the Grande Padano cheese and instead chose the baked apple in wine dough and vanilla sauce. They also offered iced coffee Vienna Style.The restaurant served a really good lunch, maybe the best of the trip. Nevertheless, I could not suppress the wish that we could have had the opportunity to lunch in Uglich and discover what the people there liked to eat. Was that really so impossible? In honor of Giacomo and Franklin I probably would have tried the Чёрный Кот.

At 1:30 I entered the Sky Bar to sit in on Tatiana’s talk on Yeltsin and Putin. Until I got there, I was not even sure what Tatiana looked like.She started her talk with an interesting quote. An economist had said that in the early nineties Russia was on the edge of the abyss, and Gorbachev helped it take a great step forward. It took the country until 2007 to get the economy back to the level that it had achieved in 1992. The price of oil was only $8 per barrel under Gorbachev.

Gorbachev’s successor, Boris Yeltsin, gave the order to destroy the house in Ekaterinburg in which the Romanov family had been shot by the Bolsheviks. Evidently he did this because he was ashamed of the act.

Yeltsin was certainly a man of the people. He took the Metro and he shopped at GUM, which was still a popular department store in the nineties. He resigned from the Politboro. He was elected speaker of the first Soviet parliament.At the time of the attempted coup, Yeltsin famously stood on a tank in Red Square. He demanded that the conspirators bring Gorbachev back. The coup collapsed, and Gorbachev resumed control of the government.

In March 1911 Gorbachev asked the fifteen republics whether they wanted to stay together or to become independent. The three Baltic states – Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia – refused to vote and just seceded. The Ukraine also voted against union, but the other eleven voted in favor because each of them knew that they were dependent on one another. For example, the parts for Lada automobiles were manufactured all over the Soviet Union.

Yeltsin was elected as the first president of Russia. On December 8, 1991, Yeltsin and the presidents of the Ukraine and Belarus signed a document that declared the Soviet Union defunct. Gorbachev was at that point the leader of a non-existent country. Only in Russia!

Russians did not know what to think of this form of government. People called a rubber police baton “the democratizer.”

Yeltsin persuaded the people to vote for “a presidential constitution,” which gave the president a great deal of power. Yeltsin himself did not actually use the power much; for some reason he let other people do most of the governing. His “five hundred days of reform” had appalling results. Nothing was available on the shelves of the stores, and prices skyrocketed. The “shock therapy” was all shock and no therapy. People said that if his economic policy was an experiment, he should have tried it on rats first.In those days some people were paid no salary for six months or even more. The miners in the east were not paid at all for two years.

Tatiana told a joke about an American dog and a Russian dog. The American dog confidently asked, “How do you like democracy?” The Russian dog said, “Well the chain is longer, but they have moved the food dish even further away. But I can bark as loud as I want.”

Russia was forced to import grain, which everyone knew was ridiculous. Russia had an abundance of land and exceptionally fertile soil. Yeltsin implemented new financial reforms every two years. Inflation in 1990 was 2500 percent. For a short period of time everyone in the country was a millionaire. An annual salary of two million rubles was not enough to supply a family with food.During the nineties seven hundred thousand children were abandoned in Russia. Over one million children did not attend school. The ruble collapsed completely in 1998. Yeltsin was desperate. He implored seven obscenely rich men to fund the pension payments. They agreed to do so, but in return they demanded a share of some of the state enterprises. The plan was called “Loan for shares.” Yeltsin endorsed it because he feared that if he did not, a civil war might erupt.

Even with his poor record Yeltsin won reelection. Only 6 percent told polls they would vote for him. In point of fact, the people voted against the Communists, who were the only significant opposition, not for Yeltsin. The people close to Yeltsin wanted him, and they did what needed to be done to make sure that he won.Tatiana said that Communism was a good system for old people and children. Activities, including sports, were free. Russians were free to travel throughout the Soviet Union and the satellite nations, and they did. According to Tatiana, the younger generation of Russians, was vigorously opposed to the return of Communism. Older people were not so sure.

Yeltsin borrowed a great deal of money from the International Monetary Fund. By the end of the nineties he had had enough of the job. He found a virtually complete unknown to succeed him. Vladimir Putin met Yeltsin’s only requirement: He guaranteed that Yeltsin and his family would not be prosecuted for corruption.

Putin was born in St. Petersburg in 1952. He was the first Russian leader since the czars who had been baptized. He was very protective of his family’s privacy. His daughters’ faces have not been seen in years, not even in photographs. He was a judo champion, and he was very good at other sports, too.At the end of the nineties Putin had nearly hit bottom. He had resigned from his administrative post in St. Petersburg after his patron lost the election for mayor. His dacha had burned down. Then, out of the blue, Yeltsin miraculously appointed him as prime minister. Yeltsin abruptly resigned on December 31, 1999, and endorsed Putin. Putin won the election in March, 2000, with 62 percent of the vote. He was re-elected in 2004 with 71 percent.

In Russia 60 to 70 percent of the people were reportedly baptized. Putin did a lot to help the small churches. He met with Pope John Paul II in Rome. He made the mistake of inviting the pope (a Polish Catholic pope!) to visit Russia. He withdrew the invitation because of intense pressure from the patriarch. I could have told him that that idea would never fly.Many Russian families did not dare to have children in the nineties. There were only eight-eight men for every one hundred women. No wonder those brides seemed so happy. Under Yeltsin the expected life span of men was only fifty-nine, while that of women was seventy-two.

Tatiana quoted statistics from a recent year: Forty thousand Russians died from road accidents and a like number from accidental alcohol poisoning. The road deaths dropped to twenty-seven thousand in 2009.

By 2010 salaries were guaranteed. Putin had implemented tremendous changes in the small cities. His plan had six elements: 1) Fight poverty. 2) Eliminate corruption, about which Tatiana was not optimistic.[5] 3) Restore law and order. 4) Pay off debts (American). 5) Maintain vertical power – the regional governors were appointed by the president. 6) Establish a state-regulated economy.

Journalist Anna Politkovskaya of the Novaya Gazeta, who famously wrote against the war in Chechnya, was murdered in 2006. The crime is still unsolved. Four journalists investigating corruption had been killed.Gary Kasparov, the chess champion led the opposition, but his ideas had gained little traction. The people liked Putin. In addition to turning the economy around and restoring order, he managed to bring the 2014 Winter Olympics to Russia.

Perhaps Yeltsin’s dumbest idea was to hold a contest to find a national idea for Russia; he may have been the first leader in the history of the world to admit that he did not have a clue. Another contender was his idea to change the national anthem to something that no one knew.[6] Putin restored the old familiar one with slight changes.

The oligarch Mikhail Khodorkofsky, who was once the wealthiest man in Russia, was arrested for fraud, tax evasion, and general mischief, convicted by a jury, and thrown in prison. He was still there at the time of the cruise.In 2000 Chechnya was attacked, and resistance was suppressed. This caused the dissidents to resort to terrorism. One thousand people had died in the conflict.

Alexander Solzhenitzyn refused a medal that was given to him by Yeltsin, but he accepted the same award from Putin.

Putin selected Dmitry Medvedev (accented on the second syllable, and there is a y sound before each of the e’s), a complete unknown, to run for president. People obviously voted for Putin, not Medvedev. Tatiana claimed that the election was fair, but she admitted that not all candidates had access to the media.

Russia covers nine thousand miles east-west and three thousand north-south. There were no roads in the eastern part of the country. Russia’s population in 2010 was 143 million. A group of Old Believers had recently been discovered. They had heard about neither world war and were also ignorant of the Bolshevik revolution in 1917.The temperature in Siberia can reach -90 degrees Fahrenheit. One location in Russia can vary from 122 to -58 degrees Fahrenheit. 25 percent of the country’s land is in Europe.

This was a good talk. It was informative without being preachy. It made me think about what it must have been like for Russians to have a democracy (of sorts) forced upon them. It was amazing that they managed to gravitate to something that was by any estimation much less repressive than anything that they had lived with since the days of Alexander II.

After the lecture I worked on my journal on the deck outside the cabin for a few minutes. I had to move to the other side of the ship to stay in the sun. At about 4:30 I was interrupted by Sue, who told me that I had to go to the Panorama Bar for Tea Time.

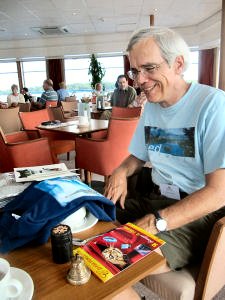

We had a nice little birthday party there. I got two cards (in Russian) from the cats,[7] a bell to use in the monastery game, a set of Patriotic War shot glasses, a tee shirt, a linen shirt, a CD by Виват, the choir that I liked in Yaroslabl. The best part of this was that the addition of the two clean shirts to my wardrobe meant that I would not need to do laundry again.Incidentally, the cookies and the tea were quite good. Tom liked the rock-hard rings. I was beginning to wonder about his taste, although I had to admit that I had not tried one.

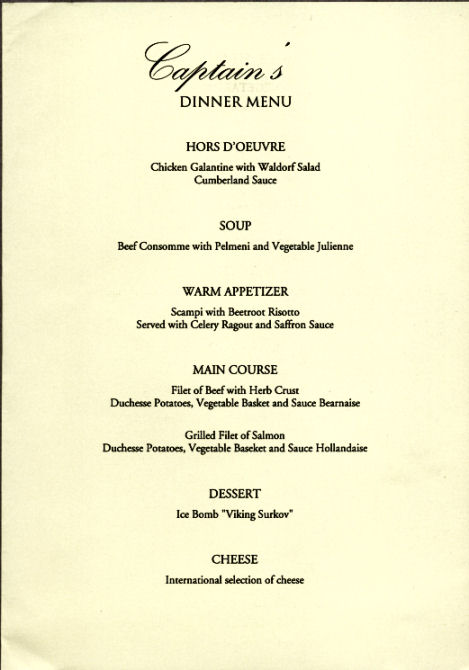

This was the night of the Captain’s supper. There was a long reception line. I guess some people liked this kind of thing because it gave them a chance to thank some of the staff in a personal way. I have always found it to be an annoying waste of time.

I did not write down what we had to eat, but I stole one of the menus.

Louie took a picture of the four of us at supper. I noticed during the meal that two other people celebrated their birthday. When they brought me my birthday cake, Julia cut it. There was way too much for four of us. The talent show after supper was silly, but fun. Polina was an excellent mistress of ceremonies. One of the guys who danced with the Cossacks got the show going by singing a funny song about two mermaids. Then Walter and his wife did a tango. The tour guides and Philipp put on a comically wooden version of Cinderella. Liana got the most laughs with her “All right” lines. A special treat was a surprise appearance from a group of lovely young ballerinas from the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. The passengers put on a melodrama about the abduction of a princess. I wondered how they decided who got to play the tree. It was a better part that you might think; Kristen spent most of the play tied to it.

[1] My notes were unclear as to which of the churches contained this fresco. There were two or three in the Kremlin.

[2] So the name is spelled in the book that Sue bought. The Russian version is Димитрий.