This was to be our group’s second travel day. I packed as carefully as I could because I was notorious for leaving items behind in hotel rooms. I signed on to the Internet and checked my e-mail before the 7 a.m. breakfast. There was nothing of note.

Sue and I ate breakfast with Ed and Charlotte. Sue volunteered the information that Benino seemed to be very “artistic.” He was reportedly considering staying in Europe so that he could go to school in Paris or Milan to become a hare-dresser. In one way the stay in Vieste left me feeling a little empty. We were very busy, and I think that everyone had a good time. We got a good feel for the coastline, but there was not enough time, at least for me, to explore the town itself. Basically we went up for supper and down for the bus and the boat. I left with absolutely no feeling for where anything was in Vieste. Perhaps I could have managed my time better.The group assembled in Piazza del Seggio for the trek back to the bus. Living in a town like Vieste must be strange. The streets were so narrow that all but the smallest vehicles were prohibited. Giuseppe’s little truck was parked in the piazza, and he loaded our luggage onto it and departed before we did.

We quickly discovered that the cats that ruled the piazza in the evening were still there in the morning. Or maybe they worked in shifts.

The weather was rather nice again, but the forecast was for it to become cooler starting on this day. Still, no rain appeared imminent. We had to be grateful that the weather had been so spectacular for the day that we spent in Vieste. The hike down to the marina, the hours on the Jessica, and the outdoor dining would have been much less enjoyable in inclement weather.As we hiked back through town to the bus, I also appreciated the fact that we were not required to schlep our luggage. I don’t know if Sue – and a few others in the party – could have made it.

Our route took Giulio’s bus along the southeast side of the Gargano Peninsula. We then planned to head down the coast on the A14 past the famous port city of Bari[1] and then continue on the S16 to Monopoli. Then Giulio would turn the bus inland toward Alberobello, where we would get a good look at the trulli houses and participate in a wine-tasting. Our final stop was to be the amazing city of Matera.

As usual Rainer made the bus ride interesting by filling us in on cultural, economic, and historical details of each area through which we were passing. I had my blue neck pillow at the ready for the dull periods. I also hoped to be able to get a little work done on the journal.As the bus drove past the nearly empty beach south of Vieste, Rainer informed us that through mid-September it had been packed with tourists. Each section of a beach in Italy was run by a beach club. Bathers could rent an umbrella and a stretch of sand from the club for the day. There were very few free beaches in Italy in 2011, and, according to Rainer, the ones that were free were not very well maintained. It was like going to the toilet in Europe; people got used to paying a little bit for the use of the facilities.

Vieste and its environs were popular every August when Italians always celebrated their annual Ferragosto holiday for several weeks. It continued to boggle my mind that practically the entire country shut down for half a month or more.

It came as no surprise to learn that the Hotel Seggio, like practically every institution in Italy, was a family-run enterprise. Giuseppe, the father, always seemed to be around the hotel. Loretta, Giuseppe’s daughter, worked the front desk every morning. Her husband Angelo was employed as a waiter. The other waiter, I later learned from Rainer, was named Michelangelo, but he went by Michele (that’s pronounced mee-KAY-lay). Both of those guys appeared to need to shave three or four times a day.During the summer of 2011 there had been a forest fire just outside of Vieste. It threatened the town to the extent that people had been evacuated. Rainer said that when he had heard about this, he was scheduled to lead a tour group (not ours) to Vieste within a few days. Fortunately, they managed to extinguish the blaze before it reached Vieste.

I tried to visualize all of the temporary and permanent residents of Vieste simultaneously struggling to leave town on the narrow and twisted roads that our bus had negotiated, but I could not do it. Maybe a lot of them departed by sea in those rubber dinghies that the octopus fisherman used.Rainer told us that the Via Appia, on which Ezio Monti had driven us to the catacombs six days earlier, ran all the way from Rome to Brindisi, which is farther down the heel of the boot than the southernmost penetration of our tour.

This part of Italy was called “Magna Grecia.” Olives were brought to Italy by the Greeks. The colonists and their descendants discovered that they could crossbreed types that were disease-resistant with those that had desirable tastes to produce superior varieties. It was not unusual for an olive tree to live one thousand or more years. I wondered if any of the olive trees on the Tusculan hill were around in the time of Pope Benedict IX. The olive harvest in Italy takes place in November and early December.

According to Rainer, the French drink their wine with or without the accompaniment of food. The taste of the wine is appreciated per se. Italians, on the other hand, insist that the wine must be carefully paired with the food.Giulio guided the bus through the twists and turns of the highway on the southeast side of the Gargano peninsula. He honked his horn every minute or so to warn oncoming traffic that a big bus was coming through. Working on the computer was inconceivable under these circumstances.

In recent years boatloads of illegal immigrants had been brought to Italy in operations that were anything but sophisticated. The refugees just ran their boats up onto the beach, and everyone aboard jumped out. The most popular destination was the island of Lampedusa, which was south of Malta.Rainer told us the legend of Padre Pio, who was born in Pietrelcina, a small town in Campania near Benevento, in 1887 and died in 1968. His corpse, with a wax mask from Madame Trussaud’s for his face, was on display at a church in San Giovanni Rotondo, which is where he spent most of his life. As we drove along the southeast coast of the peninsula, we passed within twenty kilometers of the site.

Padre Pio habitually slept on a stone bed. He became a priest of the Capuchin order at the age of twenty-seven and reportedly received stigmata[2] three years later. Pope Benedict XV wanted nothing to do with him, but Padre Pio was embraced by the Church hierarchy as a healer and a holy man for the last decade of his life even though he had been accused of faking his stigmata, and the wounds had actually healed several times. He was canonized in 2002 by John Paul II, the pontiff who welcomed an all-time record number of people into heaven.By the twenty-first century Padre Pio had become an incredibly popular figure in Italy. A million people were present for his funeral in 1968, and over seven million people annually journeyed to San Giovanni Rotondo to view his cadaver. Pictures of the saint were almost literally everywhere in southern Italy.

During this speech about Padre Pio Jeff was standing in the rear stairwell of the bus. I have no idea why he did this.

As we drove through the countryside of Puglia, Rainer described the stone walls occasionally visible there as if they were a remarkable, almost unique occurrence. Anyone from New England would not be impressed. Stone walls are ubiquitous in New England because the entire region sits on a bedrock of granite that lies just beneath the surface of every piece of arable land. Furthermore, in New England half of the twenty-first century forests were on farms that had been abandoned long before. So, it was not at all unusual to come across a stone wall in the middle of the woods. Puglia’s soil must be rocky like New England’s, but only the parking lots in New England are as flat as Puglia’s landscape. I was astonished to see such level terrain anywhere in Italy, but it was especially surprising to find it so close to the Gargano Peninsula, which, take my word for it, is nothing like Kansas. Giulio pulled over for a break at an Autogrill. I did not buy anything; my bag of biscotti rotti had hardly been dented. Like the other two Autogrills that we had visited, this one was solar-powered. The most peculiar thing about it was the absence of activity. Our bus was the only vehicle parked in the lot. The route that we were taking was clearly off of the beaten path.Next up was a history lesson about Hannibal occasioned by our passing the coastal town of Barletta. At that point we were quite near the site of the Battle of Cannae, which occurred in 216 in the Second Punic War. Hannibal, although outnumbered, implemented a clever strategy there. The Romans had amassed their infantry in a square-shaped group while Hannibal spread his troops out in a long line that outflanked the Romans on both sides. The Roman army was routed. Hannibal then tried to surround Rome and cut it off, but he never got the Romans to surrender.

I rapidly determined that it was impossible to work on the laptop because of the intolerable glare on my display.As we passed the outskirts of the port city of Bari, we could glimps the town’s football stadium. It had been designed by Renzo Piano, a famous architect whose buildings in Europe, Asia, the Americas, and beyond have won many prizes. I had to wonder how a perennial Serie B club playing in the boondocks could afford him.

Our next class on the bus was in Italian hand gestures. Pushing the index finger into the cheek and rotating it means that something was delicious.[3] When you are hungry you can make a chopping motion at the liver. A cutting motion of the neck means that something is not happening. A tug on the eyelid tells someone to watch out. It is used to warn someone of danger or to remind them of a previous agreement. Fingertips across the chin is not an insult; it means that one does not care. Shaking the fingertips together asks someone what he/she could be thinking.The exclamation “Che casino!” (where the accent in the second word is on the second syllable) indicates that a situation is out of control. Because casino is a common slang word for a brothel, the phrase is, in Rainer’s words, a little salty.

Rainer then told us about Benito Mussolini, Italy’s ruler from 1922 to 1943. He came from Emiglia-Romagna. He galvanized support throughout the country by allying with and promoting corporate interests. At the same time he implemented public works projects throughout the south. He provided the southerners with irrigation, electricity, and drainage canals. The last helped put an end to malaria, which had previously been widespread. Even today many southern towns have mostly white exteriors, and the buildings were even whitewashed on the inside to kill the mosquitoes. If Rainer explained why the color white was considered effective against mosquitoes, I missed it.

Mussolini romanticized the typical southern character as a hard-working, vigorous peasant. Hitler studied Il Duce’s methods and copied them in order to expand the base of his support.Alberobello and Matera were not served by public transport, but in recent years they were connected by a privately run railroad.

Our stop in Alberobello would focus on a wine-tasting, which, because it was held in Italy, also included a sampling of food, and a visit to a trullo house that had been converted into a store. Giulio let us off at the train station, and we all walked together a short distance through the town. Rainer first brought us to a spot that afforded us a stunning view of the trulli houses of Alberobello.

We then were allotted a few minutes of free time before we walked to the “enogastronomia” that hosted the wine-tasting. Sue ventured into a store and encountered a problem when they could not process her debit card. Fortunately, I had brought enough cash to cover her purchase. The enogastronomia that sponsored the wine-tasting was called Tholos[4]. Rainer introduced Gino, the proprietor of the shop. His English was pretty good, but his presentation was a little hard to follow. He began the event by telling us that the most prominent grape in the region was a dark red one called primitivo. Gino’s enogastronomia was very nice, but it was small, and there were almost no chairs[5] and only the one large table that held the food. I was therefore required to eat, drink, write, hold my spiral notebook, and take photos while on my feet. This was not exactly easy for someone with only two hands. I somehow managed not to spill anything, but my one-handed photos were a disappointment, and my notes were sketchy at best. The first wine that we tasted was a white that was simply malvasia (accent on the second syllable), which I recognized as one of the components of chianti. Gino recommended that it be consumed with rather bland food. Plates that included various breads and cheeses were laid out for us. The second wine was a rosé that consisted of an 80-20 blend of malvasia and negroamaro, another dark red grape. Plastic replicas of the various grapes were suspended above the table in the center of the shop, and Gino used them to make his explanations a little easier to remember. The employees served us a number of more substantial munchies including some cheese with marmalade and chili. The third wine served was a primitivo that was 13.5 percent alcohol. It was appropriate for foods with strong tastes. We had it with salami, cheese with marmalade and onions, and a few other delicacies. The event was topped off with a digestivo of crema alle mandorle, an almond-based liqueur that was served from a small table in the back of the shop.

The wine was good; the food was tasty; the presentation was fine. Nevertheless, this was by far the least enjoyable wine-tasting[6] that Sue and I had attended. The shop was just not an appropriate venue for this; it was too crowded. Maybe others could manage this experience with no seating, but I could not. I felt frustrated and clumsy.

Rainer then led us up the street a little ways to a trullo house that had been transformed into a store. The inside was less remarkable than the exterior. It was cylindrical, of course, but the inside walls were stucco, and there was little evidence of the unusual building material. It contained a kitchen, a living room with a built-in stove, two bedrooms, a water pump, a room for animals, and a loft. The last was visible with a mirror. Sue bought a model of a trullo from the store.Rainer then led us down to the center of town, and we were allowed some time to explore it. Sue needed to mail some postcards, and she asked me to look for a post office. While I was wandering around, she found a bench on which she could raise her feet. I did not locate a post office, but I did find a mailbox. Its slot was so high that Sue, who is of average height, could barely reach it.

I sauntered down the main street for a few blocks until I came to a most unusual asphalt parking lot on the left. The lot separated a park from the street. Between the parking lot and the park was, at least by appearance, a set of stone bleachers that formed an S-shaped curve. It was difficult to imagine their function. Was the parking lot used as an outdoor theater of some kind? If so, what was the purpose of the curvature? Was the stone just for decoration? It still puzzles me.Almost as soon as we left Alberobello on the road toward Matera we noticed that the landscape began to change significantly. It was still flat, but it suddenly seemed much drier, almost barren. We had entered the region of Basilicata, one of the poorest areas of Italy. By the time that we reached Matera the sun was low, and the wind had picked up.

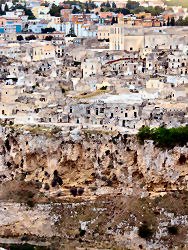

Giulio did not bring us directly to the town of Matera, which is situated beside a rather deep canyon with a trickling stream at its bottom. Instead, he parked the bus at a scenic overlook on the other side of the canyon. The view was assuredly unique, even astounding. I had read about it, I had seen photos of it, and I had looked at maps. None of this prepared me for that first glimpse. I am not sure, in fact, that it is possible to describe it accurately. Even tons of photos do not capture the experience of one’s first view of this remarkable town. Matera, which had been settled since paleolithic times ten thousand years ago, could really be considered three towns. On the top was the new town, which contained modern multi-story structures. The other two towns were the so-called Sassi, which were built right into the side of the canyon. From our perspective on the east side of the canyon, the Caveoso was on the left and the Barisano was on the right. The Caveoso section formerly housed the shepherds and peasants. They lived in caves that were hardly enhanced at all. Most were still deserted. The Barisano at one time was home to the craftsmen and laborers. Many of these had now been converted into modern residences or commercial enterprises. The man who put Matera on the map was Carlo Levi, an activist physician and painter who in 1945 published a book called Christ Stopped at Eboli, a memoir of his period in exile in Basilicata. It vividly described the shocking conditions in Matera. At that time all of the residents lived in caves without electricity or running water. The hygiene was deplorable, especially among those living in the lower areas, because the residents just dumped their waste into the canyon. The Materani lived a hand-to-mouth existence that was shocking to everyone in the twentieth century. A politician named Alcide De Gaspari spearheaded the effort to modernize Matera. It began with the subsidized construction of the new town and implementation of the utilities necessary for civilized living. The troglodytes were then evicted from their homes and provided with apartments in the new town. The homes in the caves were boarded up, and no one was allowed in for twenty years. Of course, many of the evicted had a very hard time adjusting. The next step, which began in the eighties, was to allow development of the Sassi. Renovation began in 1986. Those willing to improve the properties were given 99-year leases and provided with funding that was 50 percent loan and 50 percent grant. They were not allowed to sell the houses. After thirty years they were charged a little rent. Development proceeded under strict regulations. Plaster had to be used with white windows. The pipes had to be made of terracotta. In 1993 UNESCO declared Matera a World Heritage Site. It was extremely difficult to provide the utilities to these areas, and some of them were still abandoned in 2011. Eventually the old residents became ashamed of their previous existence, and they wanted to forget the Sassi and remain in the new town. None of them had returned to the Sassi. The city of Matera had meanwhile become rather prosperous, at least by Basilicata’s standards, but Rainer reported that it was still uncommon to see tourists there. Maybe so, but on the outskirts of the city I saw a sign advertising the Hilton Garden Inn.

Mel Gibson shot his movie The Passion of the Christ in Matera. An Italian movie, The Gospel According to Matthew, had also been filmed there in 1964.

Our headquarters in Matera was the Locanda di San Martino, which was located right in the Sasso Barisano. Reaching it required a very steep and twisted walk down from the piazza in which Giulio had dropped us off. Fortunately our luggage was again transported for us. By the time that we got to the hotel, it had turned cool outside, but it was quite hot within. Room 18, which was labeled as “della Fornacetta,” which means “of the little furnace,” smelled a little smoky. Our room had no windows at all, but fortunately the top of the door could be opened without opening the bottom. Shortly after our arrival at the hotel, the group assembled for supper at a restaurant named Il Terrazzino, which, needless to say, required a climb. Sue and I were in the last group to arrive. The only seats available were with Ed and Charlotte. Sue and I loved both of them, but we really had not gotten to know the rest of the group. We would have preferred to mingle a little.This was a real feast, the most opulent of the entire tour. The antipasti included olives, onions, salami, mozzarella and ricotta cheese. The primo was a troccoli ragu. The secundo was mixed grill of sausage, lamb, pork, and something else. I liked the sausage best. Dessert was gelato. Red wine accompanied the meal, which I really enjoyed. I gave the grinding cheek sign to Rainer after supper, and he relayed it to the owner.

The walk back to our room wore Sue out. When we got back to the hotel, she learned that the Corcorans had not returned to the States after all because their flight had been canceled. They were scheduled to try again on Saturday. Che casino! I felt sorry for them, but there was nothing that we – or anyone else – could do.

[1] I heard an interview in which Italian movie and television star Lino Banfi claimed that the locals pronounced the name of this city like the English word berry.

[2] The term stigmata refers to the five wounds that the crucified Christ received on his hands, feet, and side. St. Francis of Assisi was said to be the first saint to receive these wounds. However, no one wrote this when he was alive, and he met with Pope Innocent III, a tireless correspondent. St. Catherine of Siena’s stigmata were visible only to herself. Padre Pio wore fingerless gloves almost all of the time.

[3] Rainer also provided a few of the many Italian words that can be used to praise food. I think that he mispronounced one, squisito, which should be accented on the middle syllable: squee ZEE toe.

[4] Since Italian and other Romance languages do not have a “th” sound, the name is probably Greek. The “os” ending provides another clue.