Chapter 23: Prisoners in the Vatican

Who Was That Guy?

Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti, who became Pope Pius IX in 1846, may be the most enigmatic of all pontiffs. A few pages of biographical tidbits are as likely to mislead as illuminate his character. His pontificate stretched to 1878, by far the longest ever[1] and arguably the most important. It coincided with the Risorgimento, the most turbulent period in Italian history.

His was an upper-class family in the town of Senigalia near the Adriatic coast. As a young man he was the Fonz of the Ravenna-Ancona corridor, a smooth talker with slick threads. Perhaps attracted by the snazzy uniforms, he showed much more interest in joining the pope’s Noble Guard than in his studies. In those days, however, he suffered from recurrent fits of some kind, perhaps even epilepsy, and the malady subverted his military ambition. Shortly after his rejection by the guard,[2] Giovanni came under the influence of Pope Pius VII, the pontiff who spent six years as Napoleon’s prisoner. They may even have been distant relatives. Giovanni turned over a new leaf, studied theology, and was ordained a priest. Having devoted his life to God and the Church, he credited divine intervention for the abatement of his illness. At the age of 35 he became Bishop of Spoleto, in which position he persuaded four thousand revolutionaries on the run from Parma and Modena to disarm and disband. He then not only dissuaded the Austrian commander from acting against them; he convinced him to finance their return home. It was a remarkable accomplishmentMastai-Ferretti became renowned for his preaching. He skillfully staged suggestive moods for his homilies, which he often delivered in near darkness. A candle embedded in a skull strategically placed in the pulpit dramatic illuminated his prominent and comely features. There was little chance of anyone nodding off during these spellbinders.

In the conclave of 1846 Mastai-Ferretti was considered the “liberal” challenger to the intransigent Cardinal Lambruschini. The latter had made many enemies as the power behind Pope Gregory XVI. Cardinal Mastai-Ferretti, a robust fifty-four-year old, was selected in only forty-eight hours,[3] the shortest conclave in centuries.Pius IX hit the ground running. He revoked Lambruschini’s bans on railways and gas lighting. He boldly released thousands of political prisoners. No one could predict what would happen when the doors to the many papal penitentiaries were thrown open.

The political amnesty liberated over three thousand respectable citizens of Rome. The opening of the cells of the papal prisons revealed scenes only equaled when the people of Paris threw open the dungeons of the Bastille. ... The cells were opened in the presence of the multitude, and the liberated prisoners were the object of the deepest interest to all.

When taken from their cells and brought to the light among the large crowd of their friends and relatives, they looked astonished and bewildered, as if suspecting that the triumph was but a dream. Many of them were entirely disabled and worn out by ill-treatment, and some were brought blindfolded, upon chairs, because the slightest movement and the light would have injured them. Among them, in Rome, was a venerable old gentleman, carried by four of his sons, all full-grown men, formerly his fellow prisoners. A ray of joy animated his dying face, and his heart was overwhelmed with happiness at the imposing sight of the Roman people, once more free, and evidently determined to maintain their freedom. Excess of joy terminated in a few days his already worn-out life. His last words were, “Never trust a pope.”[4]

At first, however, everyone scoffed at the old man’s warning. Pope Pius’s popularity expanded with each measure he implemented to relax the troglodytic restrictions imposed by his predecessors.

The Romans now uproariously acclaimed and applauded the Sovereign Pontiff on every possible occasion, continually clamoring for his appearance on the loggia of the palace, where he showed himself willingly enough to distribute smiles and blessings. He was genuinely solicitous of his people’s happiness but their ovations turned his head, as they were meant to do. He found it an irresistible temptation to raise storms of enthusiasm by granting a concession here and there; for the Pontiff’s weakness, a weakness, alas! which was to deliver him bound hand and foot to his enemies, was an inordinate thirst for approbation and popularity.

Petitions now rained at the Quirinal and bit by bit Pius yielded to all the mob’s demands, being cheered to the echo in consequence. After the demolition of the ghetto and such-like minor requests had been conceded, came a persistent cry for a general amnesty and later for the expulsion of the Jesuits, which went sorely against the grain but which Pius dared not refuse. He became the idol of his people; they surged round his carriage whenever he left the Quirinal, occasionally, such as after the granting of the general amnesty, unharnessing the horses to drag the lumbering coach themselves. They yelled themselves hoarse with vivas.[5]

Italians called him “Pio Nono.” No matter what they were celebrating or protesting, the lusty cry of “Viva Pio Nono” emanated from their throats.

Revolution I

For two years the pope placated many Romans through these concessions without ever relinquishing much authority. He granted a constitution of sorts to the Papal States. However, several towns in northern Italy had gone much farther. They had revolted against Austria, and Savoy assisted their struggle for autonomy. On April 29, 1848, despite strong popular pressure for a national war of liberation, the pope announced that the Papal States would not participate in any action against the Catholic Emperor of Austria. Cardinal Antonelli, the pontiff’s Under-secretary of State, and the rest of the cabinet resigned[6] in protest. By the papacy’s historical standards, Pope Pius’s actions were quite progressive. To his dismay, however, he discovered that they failed to inoculate him against the virus of uprisings. The Hapsburg dukes of northern Italy had tried many similar half-measures. Radical Romans clamored for the pope to support the rebellions there. On November 1 the papal residence was stormed. Pope Pius took the unprecedented step of appointing Count Pellegrino Rossi, the former French ambassador, as Prime Minister. However, Rossi was assassinated on the very steps of the Chamber of Deputies on November 15. On the next day as the pope gazed through his window at the bloodthirsty assemblage outside his own residence, he seemed to experience an epiphany. On November 24 he retrieved the threadbare monk’s habit from the papal costume closet, slipped it over his papal vestments, and fled for the fortress of Gaeta, safely within the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Elections were conducted in the pope-free “Roman Republic” in early 1848. Pius IX banned Catholics from voting, but the turnout was good anyway.[7] The new government abolished capital punishment and established freedom of religion. The pope still ran the Church, but the government confiscated some papal holdings and distributed them to the poor. The pope summoned all Catholic nations to arms to help him reclaim his territories. He probably expected aid from the Austrian emperor, but only France responded. On April 25, 1849, the French Emperor Louis Napoleon landed troops in Italy. His army of eight to ten thousand easily outnumbered anything that the republicans could muster. Nevertheless, General Giuseppe Garibaldi[8] defeated the French in an early battle. He never pressed his advantage because Giuseppe Mazzini, the newspaper publisher who functioned as the civilian leader of the government, preferred diplomacy to force. Eventually the French regrouped and received reinforcements. Naples attacked from the south. On June 29, 1849, the French entered Rome, dissolved the republic, and demanded restoration of the pope. The next April French guards escorted Pope Pius back to Rome.If a liberal is a conservative who has been arrested, a liberal sometimes turns conservative after confronting his first mob. No one would ever mistake Pope Pius for a liberal again. He no longer trusted the Italians, and the feeling was mutual. Many even considered him a iettatore, one possessed of the “evil eye.” When he blessed them, they slyly extended a hand in the gesture of the downward-pointing horns to ward off his curse.

The most important long-term consequence of the revolution of 1848 was the cementing in the minds of Italians the notion of Italy as one nation. They discovered that they had much more than the word “sì”[9] in common.

Infallibility

Pius IX probably did not set out to force recognition of his infallibility; no previous pontiff felt a need for such affirmation. For decades Pius had dedicated his life to Jesus’s mother Mary. His own mother repeatedly took young Giovanni to the shrine at Loreto,[10] and as an adult he often reprised the pilgrimage. This devotion probably inspired “Ineffabilis Deus,” which declared Mary’s immaculate conception – without original sin – an article of faith for all Catholics. Because no scriptural basis was cited for this claim, some loudly questioned the pope’s right to amend the Church’s creed. Since the fourth century only the single word “filioque” had been added, and that engendered enough controversy to split the Church in two.The pope’s reasoning is difficult to follow. Had the document been submitted to Pope Benedict XIV for proofing, it would likely have been returned full of blue pencil marks. The entry in The Catholic Encyclopedia[11] is somewhat clearer, but the argumentation is still beyond the ken of someone with only twelve years of Catholic schooling. Unfortunately, Sister Mary Immaculata never taught this subject, presumably because any explanation of an “immaculate conception” would inevitably require delineation of “conception,” a taboo topic.

Several popes had incontestably issued statements that flatly contradicted their predecessors’ edicts. How then could the bishops affirm that every pope had been infallible? One loophole exempted statements issued under duress. This explained away the writings of Liberius, Vigilius, and pontiffs maltreated by various kings and emperors. The out for other troubling cases was the qualifying phrase “ex cathedra” used in the council’s definition of infallible papal declarations. The pope is only considered infallible when he addresses all Christians. Most papal decrees, including many controversial ones, were addressed to specific people or groups.

- Pope Honorius I’s heretical[13] letter containing the phrase “one Will” was addressed to the patriarch of Constantinople. It was not considered ex cathedra.

- Pope John XXII’s sermons denying beatific vision were delivered in church to specific congregations. He never published them in a papal bull.

- “Vix Pervenit,” Pope Benedict XIV’s denunciation of usury was addressed to the “Venerable Brothers, Patriarchs, Archbishops, Bishops and Ordinary Clergy of Italy.”

- Apparently none of the contradictory papal statements on abortion was addressed to all Christians.

- Few of the dubious claims concerning indulgences ever appeared in official papal publications, let alone encyclicals addressed to all Christians.

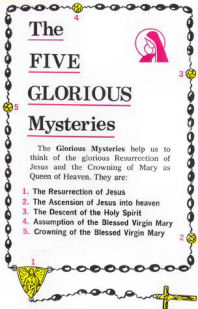

“Such cynical sarcasm is generally the devil’s work. Rather than pass judgment on the Holy Father, you should say the rosary and meditate on the Glorious Mysteries. Can you recite the five Glorious Mysteries for us?”

“Uh, the first Glorious Mystery is … Uh, no, Sister.”

“Well, learn them by tomorrow so that you can stay in at recess and write them on the blackboard one hundred times.”

“Yes, Sister.”

So Much for Liberalism

Pope Pius was very fond of December 8. On that day in 1864 he issued the famous encyclical “Quanta Cura,” to which was attached the “Syllabus Errorum,” his list of erroneous liberal ideas. Although several items were contradicted by the Second Vatican Council in 1965, The Catholic Encyclopedia says that the Syllabus “has done an inestimable service to the Church and to society at large by unmasking the false liberalism which had begun to insinuate its subtle poison into the very marrow of Catholicism.”[14] There was no apparent duress, and it was addressed “To Our Venerable Brethren, all Patriarchs, Primates, Archbishops, and Bishops having favor and Communion of the Holy See.” Here are a few of its controversial propositions:- “… (men) do not fear to foster that erroneous opinion, most fatal in its effects on the Catholic Church and the salvation of souls, called by Our Predecessor, Gregory XVI, an ‘insanity,’ that ‘liberty of conscience and worship is each man’s personal right, which ought to be legally proclaimed and asserted in every rightly constituted society; and that a right resides in the citizens to an absolute liberty, which should be restrained by no authority whether ecclesiastical or civil, whereby they may be able openly and publicly to manifest and declare any of their ideas whatever, either by word of mouth, by the press, or in any other way.’”

- “[It is an error to say that] man may, in the observance of any religion whatever, find the way of eternal salvation. … [It is an error to say that] good hope at least is to be entertained of the eternal salvation of all those who are not at all in the true Church of Christ..”

- “[It is an error to say that] the Church has not the power of defining dogmatically that the religion of the Catholic Church is the only true religion.”

- “[It is an error to say that] in the present day it is no longer expedient that the Catholic religion should be held as the only religion of the State, to the exclusion of all other forms of worship.” This responded to the tendency of nineteenth-century governments not to force one religion on its citizenry.

- “[It is an error to say that] it has been wisely decided by law, in some Catholic countries, that persons coming to reside therein shall enjoy the public exercise of their own peculiar worship.”

Revolution II

By the 1860’s Italians were fed up with the idea of being ruled by the pope. Pius IX had lost support among European powers as well, although some still liked the idea of an impotent monarchy as a buffer between the united southern Italy and the north, which, if not united, was at least mutually simpatico. Austrian forces, which helped the pope defend the Papal States for a decade, withdrew in 1859. Piedmont, the region bordering France and the sea, under the leadership of the Savoy King Victor Emmanuel II and his brilliant prime minister, Camillo Benso di Cavour, spearheaded a campaign to unite Italy. Initially Savoy controlled only the Piedmont and Sardinia, but Cavour, who died in 1861, had big plans. Savoy claimed the Romagna after a revolution there; takeover of Umbria and the Marches required the use of military force. Savoy then defeated the papal mercenaries at Castelfidardo and Ancona and seized all the papal territories except greater Rome. In 1870 after war broke out between France and Prussia, the ten thousand French troops protecting Rome were recalled. Without its foreign defenders the city soon fell to the tiny Italian army. The new civil government in Rome quickly dismantled the last Jewish ghetto in Europe and implemented many other reforms. It allowed the pope to use the Vatican without granting him sovereignty over it. Pope Pius never accepted his new role as a strictly spiritual leader. His secretary of state, Cardinal Antonelli, and the Catholic press successfully portrayed[17] him abroad as the “prisoner in the Vatican,” even though Victor Emmanuel himself had ordered the pope treated as a monarch, not a prisoner, with full use of the Vatican, the Lateran, and Castel Gandolfo, his traditional summer residence. Some prison. The new government provided the pope a military escort if he wished to travel. Pope Pius refused every offer. Instead he sulked in his luxurious apartments for eight years. He considered himself unjustly immured just as Pius VI and Pius VII had been abused and detained by Napoleon. “In countries outside of Italy it was a general belief that Pope Pius IX was kept in a dungeon, and slept on straw. Straw, it is said, was sold in Ireland as that on which the Holy Father had lain.”[18]Few Italians considered this pose noble; the pope seemed more like the last despot selfishly refusing to recognize the popular will. He was a sore loser, too. He ascribed the flooding of the Tiber in 1870 to divine retribution on Italians for depriving their pontiff of his Petrine Patrimony. He was the last papal executioner, the man who highlighted the positive side of slavery and the negative side of freedom of speech and religion, the pontiff who dismantled the ghetto and then spitefully rebuilt it. Vehement protests greeted his beatification by Pope John Paul II in 2000.

Lean to the Left?

In February 1878 the Vatican faced a peculiar problem. For eight years it had decried abusive treatment by the Italian government. How could the conclave be convened in Rome? And yet, since no other country volunteered to host the gathering, and Italy promised protection, sixty-two cardinals, all but four appointed by Pius IX, assembled in Rome. Vast material rewards were no longer associated with becoming pontiff. Being chosen would be an honor, but it would guarantee neither wealth nor a permanent lofty spot in Roman society for one’s entire family. Many cardinals were unenthusiastic about auditioning for the role of prisoner in the Vatican. Nevertheless, consensus emerged rapidly. The cardinals sought a man capable of establishing better relationships with European rulers, and one man’s diplomatic skills qualified him as well as anyone in recent memory. Within thirty-six hours Cardinal (Count) Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci, the camerlengo of the conclave, was chosen as Pope Leo XIII. Everyone assumed that the sixty-eight-year old would pilot the Church through a few transitional years until the cardinals could better gauge the force and directions of political winds. Pope Leo was considered liberal. He publicly stated that the French republican government deserved support from the citizenry. In fact, he decreed that – with one important exception – all citizens should loyally support their government’s policies. Whereas previous popes had often claimed the exclusive right to depose civilian rulers, the Church now seemed to insist that no Catholic had the right under any circumstances – save one – to disobey or plot against the government. The exception was Italy. Throughout his twenty-five-year tenure Pope Leo XIII prohibited Catholics from cooperating with the fledgling Italian state. The Church forbade both voting for and serving in the government. If Italians had heeded these mandates, it would have been a peculiar republic indeed. At every turn Pope Leo denounced the freedoms on which the Italian constitution was based. He composed a letter to the Vicar General of Rome in which he complained: “Here (in Rome) there is no restriction on the press: here Protestant churches are built even in the most populous streets as if to insult us.”[19] One papal decree stated, “They commit mortal sin who go to sing or play in Protestant churches, the publishers who print Protestant books, and the architects, contractors, masons, and laborers who work in the construction, repair, or decoration of any Protestant church. Parish priests are hereby instructed to see that no one will work for Protestants.”[20] The Church grudgingly tolerated personal freedom in other countries. However, Pope Leo emphasized that the state’s proper function was to enforce the Church’s decrees, even in secular nations like the United States! “The pope had recognized, in his encyclical to the bishops of the United States, that the separatist system [i.e., separation of Church and state] had enabled American Roman Catholicism to make decided progress; but the Holy Father also declared that this system could only be regarded as provisional, and that the true doctrine, for America as well as other nations, consisted of the close union of the civil and religious power.”[21]Little wonder that so many non-Catholic Americans feared that Al Smith and John F. Kennedy might serve as the pontiff’s puppets. Sr. Mary Immaculata and company assured us that Mr. Kennedy could simultaneously be a good Catholic and a good president, but Pope Leo’s contribution to this discussion was missing from our curriculum.

Pope Leo published eighty-six encyclicals. In the most famous, “Rerum Novarum” of 1891, the Church for the first time addressed labor-management relations. It stressed that employers have a moral obligation to treat their employees in a humane way:The following duties . . . concern rich men and employers: Workers are not to be treated as slaves; justice demands that the dignity of human personality be respected in them, ... gainful occupations are not a mark of shame to man, but rather of respect, as they provide him with an honorable means of supporting life.

It is shameful and inhuman, however, to use men as things for gain and to put no more value on them than what they are worth in muscle and energy.

On the other hand, the pope circumscribed the rights of labor with phrasing that describes the obligations of the state in much more concrete terms than the platitudes employed with regard to management:

Labor which is too long and too hard and the belief that pay is inadequate not infrequently give workers cause to strike and become voluntarily idle. This evil, which is frequent and serious, ought to be remedied by public authority, because such interruption of work inflicts damage not only upon employers and upon the workers themselves, but also injures trade and commerce and the general interests of the State. … The laws should forestall and prevent such troubles from arising.

A controversy about “Americanism” surfaced during Pope Leo’s tenure. The term referred to an allegedly heretical mindset identified with Americans, namely the willingness of Catholics to blend in with the Protestant majority – tolerate other religions, not get upset at freethinkers, enroll their children to public schools, avoid proselytizing, etc. The encyclical written in 1899 on this subject, “Testem Benevolentiae Nostrae,” was not too inflammatory.

On the other hand, his encyclical “Humanum Genus,” issued fifteen years earlier to condemn Freemasonry, troubled Americans. Many of America’s founding fathers and heroes were Masons.[22] Since the encyclical’s first paragraph divided the world into two parts, the kingdom of the Church and the kingdom of Satan, people reasonably inferred that the pope placed America in the devil’s camp. After blaming the Freemasons for the loss of the Papal States, he enumerated the characteristics of governments unduly influenced by Freemasonry – free public education, freedom of worship, freedom of assembly, a free press, separation of church and state, and equality. He also attacked socialism and communism. This encyclical must have reinforced the suspicious feelings that some Americans harbored toward Catholics, especially recent immigrants. The only Mason familiar to the kids in Sr. Mary Immaculata’s class was Perry. Some of us had noticed buildings called Masonic Temples, decorated with cheese knives and pyramids and other outré symbols. We knew about temples; heathens performed their demonic ceremonies there mutilating goats and babies and such. Learning that George Washington and other founding fathers had ever set foot in such places, would surely have triggered cognitive dissonance, at least until the bell rang for recess. Pope Leo perfected the newspaper trick invented by Pius IX. In 1850 the Jesuits began publishing the periodical La Civiltà Cattolica. The Vatican’s daily newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, debuted in 1861. During the 1890’s the number of Catholic publications in Italy alone grew to five hundred, including thirty dailies. David I. Kertzer has convincingly demonstrated that the papacy used these publications to blame Catholics’ problems on Jews and Freemasons.[23] The papers associated the former with usury, money-grubbing greed, and the ritual murder of Christian children to obtain blood for Passover rituals. Italy’s republic claimed to have inherited the power of exequatur, the right to approve ecclesiastical appointments, from the Austrian government that it had unseated. Eventually thirty bishoprics in Italy became vacant because papal appointments lacked the government’s approval. Giuseppe Sarto, the man who eventually succeeded Pope Leo, was not allowed to assume the patriarchate of Venice. In August of 1894 Prime Minister Francesco Crispi withdrew the government’s claim in exchange for an Apostolic Prefecture in the Italian colony of Eritrea. Pope Leo also sent a group of Italian Capuchin monks to replace the French Lazarists there.A poetic soul, Pope Leo loved Dante. His own verses were written in Latin. A collection of the pope’s greatest hits, Carmina Novissima, was released during his pontificate. It may well be the last book of serious new Latin poetry ever published.

The Marian Cult

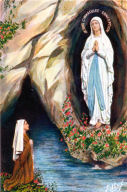

The nature of Jesus’s mother Mary has long been controversial among Christians. The Bible says little about her; in fact, she plays a much larger role in the Qu’ran. Matthew’s gospel unequivocally stated that she was a virgin at the time of Jesus’s birth.[24] The notion of Mary’s purity was later extended to include the postulation that she remained a virgin throughout her life. The Bible’s mentioning of Mary’s other children posed a challenge, but over the ages Church doctors concocted various ways of dismissing these difficulties. When Pope Pius IX decreed in 1854 that Mary was pure before she was even born, it became dogmatic that she was conceived free of original sin, the so-called Immaculate Conception.

In 1858 a very devout teen-aged girl named Bernadette Soubirous reported visitations from a mysterious Lady in a grotto in the French village of Lourdes. In the eighteenth “apparition” she called herself “The Immaculate Conception” – the pope’s very term. Her nomenclature was considered proof of the legitimacy of the apparitions, even though they had been invisible to the large crowds nearby. It was deemed a miracle because nothing else could possibly explain the fact that news of the Supreme Pontiff’s encyclical had reached all the way from Italy to neighboring France in as little as four years.Pope Pius IX actively supported the devotion to Mary based on this and other reported apparitions. A key facet of the Marian cult is praying the rosary – the recitation in a particular order of an Apostle’s Creed, fifty-three Hail Mary’s, and a handful of Our Father’s and Glory Be’s. Meditation on enumerated theological mysteries is prescribed during five breaks. The familiar beads[25] are used to track one’s progress in the ritual. Pope Leo continued his predecessor’s supportive attitude toward the cult. He composed eleven encyclicals concerning the rosary, which was also the topic of an approved apparition in Naples in 1884. He also had a replica of Bernadette’s grotto constructed in the Vatican garden. One of the first commercial films ever made showed the pope strolling there in 1898.The Papal Fountain of Youth

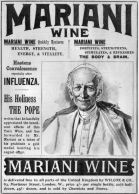

Pope Leo lived to the age of ninety-three. No pontiff, or at least none for whom records are reliable,[26] has lived longer. How did this man, who at his election was considered somewhat elderly and sickly, live so long? Intelligent guesses might focus on the stress-free nature of the new papal job description. The pontiff no longer governed a country or even a city. No one recognized his claim to sovereignty over the Papal States. In keeping with his public image as a prisoner, he remained in the Vatican during his entire pontificate. However, a life of ease cannot explain his longevity. In fact, the ancient pope was a workaholic. He put in incredibly long days writing letters, encyclicals, and poems. “The Pope and his secretary often work sixteen hours a day … Leo XIII sleeps very little, and as he cannot abide inactivity, he often fills up the time waiting for Morpheus by wooing the Muse, or thinking out some encyclical whereof the first few sheets are lying on his writing table. … His excessive devotion, it might be said, finds nourishment in the excessive fatigue to which that devotion condemns him.”[27]How many nonagenarians can manage sixteen-hour work days? Well, Pope Leo, for one, had chemical help. He habitually took snuff[28] (i.e., pulverized tobacco) up his ample schnoz. His physician advised him to quit, but he never did. His other chemical dependency was cocaine. He didn’t snort lines of blow or smoke crack; he was hooked on a popular beverage called Vin Mariani, a concoction of wine laced with cocaine. Other celebrities, including Queen Victoria, also enjoyed an occasional glass of VM. Pope Leo actually authorized use of his august image in its advertising campaign and awarded a gold medal to the drink’s inventor, Angelo Mariani.

Pope Leo appointed 147 cardinals, more even than Pius IX, whose pontificate lasted seven years longer. To some extent the proliferation of cardinals reflected the Church’s global reach.

The Last Pontifical Saint

Pope Pius aimed to restore everything in the Church to Christ. That seemed an incontestably laudable goal until one remembered that Christ had been dead almost 1,900 years. A lot of holy water had passed through the stoup in the interim. For example, if Christ favored a particular type of music, the evangelists missed it. Nevertheless, Pope Pius, a champion of Gregorian Chant throughout his career, was determined to purify liturgical music. He wrote more about music than all previous popes combined. Gregorian chant was in, and baroque and classical compositions were out. That was Vivaldi, Schubert, and Mozart he expelled, not Stravinsky or Scott Joplin. Way out of bounds was the saxophone, which, according to the pope, “gave reasonable concern for disgust and scandal.”[29] In liturgical functions he banned singing in any language besides Latin. Presumably the Kyrie, the Greek chorus that is always sung in high masses, was exempt. For about sixty years the music in Catholic liturgical ceremonies was “an entirely alien musical form in a dead language.”[30]

Pope Pius devised a long oath called “Sacrorum antistitum,” which he required every clergyman in the world to swear. Its very first item is this: “And first of all, I profess that God, the origin and end of all things, can be known with certainty by the natural light of reason from the created world (see Rom. 1:90), that is, from the visible works of creation, as a cause from its effects, and that, therefore, his existence can also be demonstrated.” This refers to the cosmological proof of God’s existence, articulated by St. Thomas Aquinas, the pope’s favorite theologian. Surely Catholic priests should believe in God, but why must they affirm this particular proof over, for example, the ontological or teleological[31] proofs?[32]Professors and theologians were required to swear the oath as well. Anxiety must have reigned in the faculty lounge, because the oath specified: “I reject the opinion of those who hold that a professor lecturing or writing on a historico-theological subject should first put aside any preconceived opinion about the supernatural origin of Catholic tradition or about the divine promise of help to preserve all revealed truth forever; and that they should then interpret the writings of each of the Fathers solely by scientific principles, excluding all sacred authority, and with the same liberty of judgment that is common in the investigation of all ordinary historical documents.” Enforcement was spotty. In Italy Angelo Roncalli, the future Pope John XXIII, was investigated for merely reading suspect authors.[33] “(In Germany) exemptions were granted – with a bad grace – and concessions made. Elsewhere, this oath was taken with mental reservations, tacit or avowed, which, while they deprived it of its test value, put an intolerable strain on the conscience of the more educated clergy.”[34]

Pope Leo XIII’s foreign policy had been guided by two principles: (1) Every (non-Italian) Catholic must support his government, regardless of who, how, or why; (2) The pope would stay in the Vatican until the Papal States were restored. Pope Leo was reasonably successful at establishing good relations with every European government save Italy. He even persuaded Bismarck to mollify his policies towards the clergy. Pope Pius and his Secretary of State, Cardinal Merry del Val were less tolerant. In 1905 the pontiff refused to meet with Émile Loubet, the President of France, because he had negotiated with the Italian government. The rebuke shocked the French government, which implemented a law separating Church and state, expelled the Jesuits and most religious orders from France, confiscated the Church’s property, and severed relations with the papacy. The pope and the cardinal criticized other nations with similar results. Pope Pius fervently endorsed the other half of Pope Leo’s policy. He insisted that he too was a prisoner in the Vatican, and until the Papal States were restored, he would continue to rattle his cup against the bars. He never even returned to his beloved Venice. Moreover, he harbored a delusional “vision of an anti-democratic Italian monarchy, in alliance with which the pontiff should exercise an effective super-sovereignty under international guarantees.”[35] When World War I approached, the pope seemed to favor the Germans, or it might be more appropriate to say that he opposed the French modernists. Compared to them, Kaiser Wilhelm II seemed like a “holy emperor.”The saintly pope articulated his assault on modern ideas in the long encyclical of 1907, titled “Pascendi Dominici Gregis.” The reasoning employed therein is not for the faint of heart. It attacks “modernism,” a word seldom still employed in this context. One must slog through constructions like “For, after all, what is sentiment but the reaction of the soul on the action of the intelligence on the senses?” The modernists proposed to use the scientific method to devise a more reasonable and thus stronger religion. They discounted miracles in both the Bible and tradition. They valued the conclusions of “Church doctors” such as St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas less than those of scholars with modern exegetic tools. Pope Pius lumped with the modernists anyone who adopted any of their ideas. For example, he wrote that “there is no surer sign that a man is on the way to Modernism than when he begins to show his dislike for this system (scholasticism, the methodology of St. Thomas Aquinas).” All secular notions are in part modernist, so the papal condemnation touched many philosophies. The most quoted phrase in the encyclical is that modernism is the “synthesis of all heresies,” a statement that was not really that profound. According to the pope modernism was based on agnosticism. Since agnosticism is the polar opposite of faith, it is hardly surprising that modernistic conclusions contradicted faith-based propositions.

At about the same time the pope attempted to expand the credo in the syllabus “Lamentabili Sane,” which consisted of sixty-five statements that were officially “condemned and proscribed.” Pope Pius’s Church could never be the “big tent.” Catholics were required to embrace every pronouncement from the Vatican. Some items condemned in the encyclical were surprisingly specific. For example, items sixteen through eighteen dealt with the gospel according to John, which is inarguably inconsistent with the three synoptic gospels in a number of particulars.[36] The encyclical warned in dire terms against denigrating John’s gospel for any reason.The Vatican excommunicated the two most famous modernists, Alfred Loisy and George Tyrell, and quite a few clergy and laymen. Every book critical of either the Church’s interpretation of scripture or sacred tradition was placed on the Index. The pope longed to go even farther. In his words, “It is not enough to hinder the reading and the sale of bad books – it is also necessary to prevent them from being printed.

The Pacifist

Pope Pius died shortly after World War I began. Although he lived in a relatively innocent age, he thought that the worst – Armageddon complete with the Antichrist[37] – was imminent. A sincerely religious man, he did his best to drag humanity into the holy sphere in which he lived. His impact, however, fell far short of his intent. His efforts may have even been counterproductive. He was the Miniver Cheevy (born too late) of papal history, or maybe even Don Quixote tilting at windmills of modernism that seemed innocuous to his contemporaries.

Pope Pius’s successor, the frail Cardinal Giacomo della Chiesa, took the name Benedict XV. Facing a continent at war, he focused his efforts on bringing peace to Europe. He had no use for “just wars;” to him they were all abominable. He promoted several concrete peace proposals to both sides. Each thought that his plans favored the other. When this meat-grinder of a war finally ended, France, England, Russia, and Italy again insisted on the Vatican’s exclusion from peace negotiations. Pope Benedict publicly supported his predecessor’s pronouncements on modernism, but in private he called off the dogs. Unlike the other prisoners of the Vatican, he suppressed the anti-Semitic articles that had characterized the Catholic press.[38] In 1920 the pope canonized Joan of Arc, who had been burned as a heretic in 1431; if recognition of her sainthood was intended to curry favor with the French, it largely failed. Pope Benedict finally ended the ban on participation by Italian Catholics in their government; he even conducted a secret meeting with Mussolini, who was not yet in power, in an attempt to settle the “Roman question,” as the Church referred to its loss of the Papal States. The apparition of Mary near Fátima, a town in Portugal, occurred during Pope Benedict’s pontificate; he never certified it, but he did call it “an extraordinary favor from God.”Pope Benedict’s eight-year tenure also witnessed the Bolshevik Revolution and the onslaught of the devastating influenza pandemic. The pope donated incredibly large sums – both the Church’s money and his own family’s – to victims of war and disease. When he died of influenza in 1922, the Church could not afford his funeral expenses. Ironically, the first official day of mourning in the fifty-two-year history of the Italian state honored the Church’s deceased pontiff.

Never Let the Devil Cut the Cards

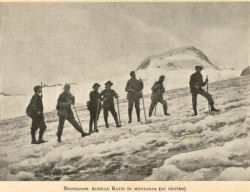

The normally reliable George Williams and others have reported that Cardinal Laurenti was elected pope in the conclave of 1922,[39] but he declined. However, the ballot-by-ballot totals recorded by Cardinal LaFontaine and Cardinal Piffi show Laurentini receiving no more than five votes on any ballot. In any case, Cardinal Achille Ratti prevailed on the fourteenth ballot. Ratti blazed a new path to the Church’s summit. A recognized expert in the translation and evaluation of ancient and medieval manuscripts, he toiled in obscurity for twenty-three years in Milan’s Ambrosian Library and for another seven in the Vatican Library. He became a favorite of Pope Benedict, who named him the Archbishop of Milan. In 1921 he became a cardinal at the age of sixty-four. So, only a year before he became Pope Pius XI, Ratti was an absolute nobody in the clerical hierarchy! His long career as a bookworm allowed him to pursue his avocation of mountain climbing. He had scaled Monte Rosa, the Matterhorn, and Mont Blanc. The new pope was a mountain-climbing librarian!Pope Pius figured that after more than a half century of isolation, the papacy should rejoin humanity. He dropped the charade of “the prisoner in the Vatican” and negotiated with the Italian government, which after October 1922 meant the Fascists. In 1926 he called Mussolini “the man sent by Providence.” The compacts completed in 1929 gave the pope sovereignty over Vatican City and little else – 108.7 acres altogether. The government compensated the Church for lost territories. The treaties banned Italian clergy from politics, but a peculiar clause allowed the Church to dictate marriage laws in Italy. Divorce was prohibited for Italians of all faiths until 1970. Mussolini soon regretted some provisions. In 1931 he dissolved the Church’s youth groups because they competed for membership with their Fascist counterparts. The pope protested this action to no avail.

Pope Pius feared the spread of Communism. In 1933 the Church negotiated with Hitler’s Germany a concordat affirming the Church’s position and its freedom to teach religion in German schools; in return the pope disbanded the Catholic Center Party and supported the Reich. Shortly thereafter the Nazis shut down Catholic presses and suppressed the unions. Young Catholics, Including Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, were pressed into the Hitler Youth. In 1937 Pope Pius issued an encyclical written in German! It harshly criticized racism without mentioning Hitler or the Reich. It was smuggled into Germany and read from the pulpit. Pope Pius XI, nearing the end of his life, swallowed his tongue when the Nazis turned words into actions in the notorious pogrom of November 1938, Kristallknacht. His Secretary of State, Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, strongly influenced his policy. Both were alarmed at the advances of Bolshevism. They may have also feared recriminations against Catholics in Germany – or even Italy – if the Church appeared too antagonistic toward the Nazis.The pope’s death on February 10, 1939, was at least somewhat controversial.

Pius XI commissioned a U.S. Jesuit, John LaFarge, to write an encyclical attacking racism and anti-Semitism. … Through a series of apparently Machiavellian machinations, the message never got into print. After examining the evidence, an editorial writer for the National Catholic Reporter stated, “Considering all this, we must conclude that the publication of the encyclical draft at the time it was written may have saved hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of lives.”… Father LaFarge wrote “Humani Generis Unitas” as requested, but apparently the Jesuit Superior General, Father Wlodimar Ledochowski, a Polish count, withheld the completed manuscript from the pope for what the NCR concluded were “political reasons.” Pius XI’s death the following February doomed the declaration to limbo. (Cardinal Jean Tisserant, a close associate of the pope, claimed that Pius XI was poisoned by a physician, Dr. Francesco Petacci, whose daughter Clara was Mussolini’s mistress. The pope died on the eve of a scheduled speech to Italian bishops that was to have been an attack on Fascism.)[40]

[1] This was despite the fact that he was one of the few popes who habitually smoked tobacco.

[2] John S. C. Abbot wrote that Giovanni quit the Guard because he was rejected by a girl named Chiara Colonna. Italy, P.F. Collier, 1889, p. 671.

[3] “And it was by accident that Cardinal Mastai-Ferretti (Pius IX) was not excluded from the Papal throne. Austria, disturbed by the liberal aspirations imputed to him, instructed its agent to lodge the formal veto in the name of the Emperor. Private information of the Imperial intention reached the conclave; the election was hurried forward, and the Austrian veto arrived the day after the election, when it was of no avail.” Malcom MacColl, The Reformation Settlement Examined in the Light of History and Law, Longmans, Green, and Co., London, 1899, p. 514.

[4] Julie Granville Marguerittes and R. Shelton Mackenzie, Italy and the War of 1859, G.G. Evans, 1859, pp. 264-265.

[5] Pirie, op.cit., pp. 329-330.

[6] Antonelli continued as Prefect of Papal Palaces and became Secretary of State in 1849.

[7] In the early days of the Italian republic only 2 percent of the people were allowed the vote. Poor peasants were not enfranchised for many decades.

[8] What a strange life Garibaldi led! He was born in Nice. He spent his young life pirating in South America. In July of 1861, President Lincoln offered him a command in the Union army!

[9] “La genti del bel paese là dove‘l sì suona.” Lines 79-80 of Canto XXXIII of Dante’s Inferno.

[10] The Santa Casa at Loreto is reputed to be the very house in which Mary received the Annunciation. Pope Leo X certified that it had been transported by angels from Nazareth on May 10, 1291. After two or three stops it came to rest in Loreto.

[11] This article contains one clause that defies commentary: “But these stray private opinions merely serve to show that theology is a progressive science.” Op. cit., Vol. VII, p. 675. Obviously this article was not proofread by Ursulines, who would never have allowed a sentence that started with a conjunction.

[12] Kertzer noted that one of the dissenting bishops was probably confused. David I. Kertzer, Prisoner of the Vatican: The Popes’ Secret Plot to Capture Rome from the New Italian State, Houghton Mifflin, 2004, p. 31.

[13] Some have claimed that in context the pope’s writing was orthodox, but the contrary evidence is strong. The letter was denounced by an ecumenical council in which the bishops shouted in unison, “Anathema to Honorius!”

[14] Op. cit., Vol XII, p. 136.

[15] Davis was an Episcopalian, but his cabinet included both Catholics and Jews. The Church denied that it recognized the confederacy, but members of Davis’s cabinet interpreted the pope’s letter as official recognition.

[16] Matthew 16:24.

[17] Despite the loss of the Papal States, the pontifical coffers overflowed with donations from abroad.

[18] Frederick Meyrick, Memories of Life at Oxford, and Experiences in Italy, Greece, Turkey, Germany, Spain, and Elsewhere, John Murray, London, 1905, p. 283.

[19] William Burt, Pope Leo XIII Judged by His Own Words and Acts, 1901 p. 23-4.

[20] Ibid., p. 24.

[21] Julien de Narfon, George A. Raper, Leo XIII, J.B. Lippincott, 1899, p. 219.

[22] Fourteen or so presidents were Masons, as were Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, Paul Revere, John Paul Jones, and Lafayette. At least thirteen signers of the Declaration of Independence belonged to Masonic Lodges. Some researchers cite much larger numbers.

[23] David I. Kertzer, The Popes Against the Jews, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2001, pp. 133-151.

[24] This declaration helped to steer inquisitive young Christian minds away from the uncomfortable subject of what might have transpired nine months before the first Christmas.

[25] In our day some nuns employed oversized rosaries as belts. When discipline was required, the rosary could readily be transformed into a miniature morning star that packed a formidable wallop.

[26] Some claim that Pope Agatho, who was embroiled in the controversy over Pope Honorius I in the seventh century, was over one hundred years old.

[27] Julien de Narfon, Pope Leo XIII, His Life and Work, translated from the French by G. A. Raper, London, Chapman and Hall, Ld., 1899, p. 141. According to this biographer, Pope Leo evidently discovered the trick of converting fatigue into energy through the medium of devotion. Free energy at last!

[28] Banned by Pope Urban VIII but legalized by Benedict XIII.

[29] Michael Segell, The Devil’s Horn, Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, New York, 2005, pp. 291-2.

[30] James F. White, Roman Catholic Worship; Trent to Today, Liturgical Press, Collegeville, MN, 2003, p. 93.

[31] Now generally referred to as “Intelligent Design.”

[32] I favor the proof attributed to the eighteenth century Swiss mathematician Leonhard Eüler: “eiπ + 1 = 0; therefore God exists.” e is the base of the natural logarithms; ex is the function that is its own derivative. i is the square root of -1. π is the circumference of the unit circle. e and π are “irrational” numbers; i is “imaginary.” Eüler seemed to argue that only with a Divine Plan could such an elegant equation bind these bizarre and seemingly unrelated numbers to the multiplicative and additive identities.

[33] Howard E. Gardner and Emma Laskin, Leading Minds: Anatomy of Leadership, Basic Books, 1995, p. 171

[34] Alfred Fawkes, “The Pontificate of Pius X,” The Quarterly Review, #450, January, 1917, p. 493.

[35] Ibid., p. 487.

[36] For example, John apparently places the last supper on a different day from that specified in the other gospels.

[37] Charles A. Coulombe, Vicars of Christ, Citadel Press, 2003, p. 409.

[38] Kertzer, op. cit., p. 241.

[39] George Williams, op.cit., p. 133.

[40] Harry James Cargas, Holocaust Scholars Write to the Vatican, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 1998, p. 13.

| |

| |

Bankable Bar Bets

$ Austria intended to veto Cardinal Mastai-Ferretti’s candidacy for the papacy, but he was elected Pope Pius IX before anyone announced the veto.

$ Pope Pius IX, #256 on the official list of popes, was the first to serve longer than the twenty-five years traditionally attributed to St. Peter.

$ The pope with the longest pontificate, Pius IX, regularly smoked tobacco.

$ Pope Pius IX tore down the walls surrounding the Roman ghetto and then reinstituted the ghetto after his exile.

$ Pope Pius IX ordered the beheading of two Italians in a Roman piazza for the crime of attacking a French garrison in Rome.

$ President Lincoln offered Giuseppe Garibaldi a command in the Union army in July of 1861.

$ Pope Pius IX sent a crown of thorns to Jefferson Davis when the latter was in prison.

$ In 1518 Pope Leo X issued a bull certifying that in 1291 angels transported the house in which Mary, Jesus’s mother, resided from Palestine to three different locations before depositing it in the Italian town of Loreto.

$ Italy has only existed as a nation since 1870.

$ Pope Leo XIII used cocaine; he drank it in a product called Vin Mariani. He even appeared in a poster advertising the beverage.

$ Pope Leo XIII habitually took snuff.

$ Despite his vices, Pope Leo XIII lived to be ninety-three.

$ Pope Leo XIII appeared in one of the first commercial motion pictures ever made.

$ Pope Leo XIII published a book of his poetry – in Latin.

$ In 1903 the Austro-Hungarian emperor vetoed the leading candidate for the papacy.

$ Pope Pius X banned classical and baroque music from the liturgy.

$ Pope Benedict XV was a pacifist.

$ The first official day of mourning in Italy was for Pope Benedict XV.

$ Pope Pius XI worked in libraries for thirty years before becoming the pontiff.

$ Pope Pius XI was an avid mountain climber.

$ The Vatican comprises only 108.7 acres.

$ Divorce was illegal in Italy from 1929 until 1970.

$ Pope Pius XI died under suspicious circumstances the day before he was scheduled to deliver a speech denouncing Hitler.