Chapter 22: Bonaparte’s Captives

Controversy dogged the long conclave of 1774. How could it not? Pope Clement XIV’s death was extremely suspicious. The Society of Jesus had been disbanded, and its leader was behind bars. Individual Jesuits remained influential, but the French and Spanish cardinals insisted on the order’s continued suppression. They controlled enough votes to enforce their will. For several months no candidate came close to attaining the requisite votes. Part of the problem was that the man running the conclave, Cardinal de Bernis, was apparently infatuated with the Princess of Santa Croce. Contact with the outside world was proscribed to those in the conclave, but Casanova claimed that the couple rendezvoused three times a day. Eventually the cardinals gravitated to Cardinal Giovanni Angelo Braschi, despite his dubious reputation.[1] Although Braschi had been educated by the Jesuits and had voiced tepid opposition to the suppression of the order, he assured the French and Spanish that he would uphold Pope Clement XIV’s decree. Braschi agreed with Casanova and many others – including Pope Clement himself – that the Jesuits had indeed poisoned the pontiff. In any event, Fr. Ricci died in Castel Sant’Angelo shortly after Braschi received his tiara as Pope Pius VI.Appearance is 90 Percent

What he lacked in experience and comportment Cardinal Braschi made up for in looks. If your screenplay’s dramatis personae included a pope, Braschi was your man. He was one of the most strikingly handsome men on earth, and he knew it. A large-framed hunk in his late fifties, he enjoyed the vigor and complexion of a much younger man. As his hairline receded he dressed and curled the hair on the sides of his head in an attractive manner. He also boasted a superb pair of legs, and he took great pains to show them off, a somewhat unexpected quality in a pope. Pope Pius’s pontificate almost perfectly coincided with the amazing final quarter of the eighteenth century. It was the age of the Georges – the hapless English kings and the incomparable American general and president. European music reached unparalleled heights in the works of Haydn, Mozart, and the young Beethoven. Philosophical ideas that for decades had percolated among intellectuals took shape in France, where bloody revolution evolved into one chaotic manifestation after another.These developments were still in the future when Pope Clement XIV died. Although many pundits praised him for ending the Jesuit controversy, his public poping was uninspiring. Clement had cared little for the public display of spiritual leadership expected by the faithful. Franciscan monks never emphasized ritual.

The papacy remained the economic engine of Rome and central Italy, and 1775 was a Jubilee year, which traditionally brought in lots of soldi. For the first month and a half of this critically important period, there was no pope at all. The holy door in St. Peter’s Basilica was still bricked shut! No one could have filled this void more dramatically than the youthful and vigorous Pope Pius VI. His clothes were always sparkling white. He habitually cocked his head for effect. He was blessed with a resonant speaking voice, and he knew how and when to strike a pose. When his pontifical hammer smashed the (previously weakened) brick wall barring the Jubilee door, the heart of every attending Christian skipped a beat. When the spell broke, onlookers rushed in to claim souvenir bricks. Rome fell in love with its new bishop. Pope Pius faced problems more substantial than the wall. First, however, he needed to provide for his family, not one of the traditionally wealthy Roman dynasties. He could only legally name one nephew as a cardinal. He did so, and he made another the Duke of Braschi-Ornesti. Redistributing existing papal territories to relatives was illegal. The pope therefore undertook the Herculean task of draining the noxious Pontine marshes southeast of Rome in order to reclaim land to donate to his sister’s children.[2] The project cost a fortune and by and large failed.[3] Although much confiscated Jesuit wealth found its way into the Braschi accounts at Banca di Roma, His Holiness exercised caution in dealing with the defunct order. The black pope had died in prison, but many supporters remained in Rome. Emperor Joseph II had implemented clerical “reforms” in Germany and Austria. Most simply transferred authority from the pope to himself. The emperor’s brother Leopold, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, paid the pope even less respect. Pope Pius surmised that the Austrians needed more intimate exposure to the pontifical persona. He amassed a huge retinue, packed up his most elegant finery, and made an uninvited visit to Vienna in 1782. Evidently unacquainted with the popular aphorism about the stench of guests and fish, he stayed for an entire month.[4] The emperor’s court barely tolerated the pope’s presence in its capital. Wenzel Kaunitz, the chancellor, brazenly shook hands with the pontiff rather than kiss his ring. He once received the pope while clothed in his bathrobe. The Holy Father, accustomed to underlings prostrated before him, was shocked and insulted by Kaunitz’s effrontery.Austrian commoners, on the other hand, were thrilled at the chance for close contact with such a grand pontiff, and Pius VI knew how to work a crowd. He appeared publicly on his balcony five times a day. The demand for kissing the pontifical feet was staggering. The pope set out one of his – presumably used – slippers so that as many Austrian lips as possible could experience the thrill of planting a smackeroo on papal footwear. A shoe without a leg? How many Austrians waited for hours hoping in vain for a glimpse of those legendary pontifical gams?The trip cost the Church a fortune, but it accomplished little. The resulting concordat effectively ratified the emperor’s unilateral policies. The pontiff did receive some lovely parting gifts and a copy of the board game Austro-Hungarian Empire!

Pope Pius loved to see his name. It was etched prominently on the cornerstone of each new building constructed during his long tenure. If the pope ordered even a small change to an existing structure, a sign “Munificientia Pii VI. P.M.” would be added to the façade to ensure credit. A statue of Pope Pius was erected in Ancona in honor of the lighthouse that he had placed in the harbor. The lighthouse was fine, but quite a few workers died from accidents associated with the statue.

Eventually the Romans tired of Pius’s grandstanding. Some would probably have preferred assistance for the needy over so much construction and embellishment. When the pontiff raised an expensive obelisk at the entrance of his summer residence, the Quirinal Palace, someone wrote at the base “Signore, dì a questa pietra che divenge pane,”[5] which means “Lord, speak to this stone so that it might become bread.” If asked, Sister Mary Immaculata might have noted that this behavior illustrated why the Church discouraged laymen from reading the Bible for so many centuries.By tradition the King of Naples annually presented to the pope a white horse, called a palfrey, and a monetary tribute. King Ferdinand IV neglected to do so. Pope Pius threw a hissy fit when his horse failed to appear. Eventually the equine portion of the deal was negotiated away, and the tribute was paid in a lump sum at the king’s accession.

The French and Pius VI

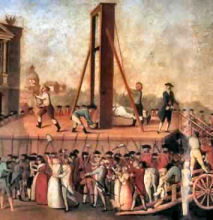

During the Bourbons’ long rule in France they bickered with the pontiffs over many issues. The Gallican Church had long insisted on an operational model that provided more independence than the norm in other Catholic countries. By the eighteenth century conflicts over this matter, the Jesuits, and the Jansenist influence in France further chilled the relationship between Rome and Paris. Nevertheless, the papacy had long ago learned to deal with monarchs of all stripes. It certainly disconcerted Pope Pius to learn in 1789 that French peasants had stormed the Bastille and that the guillotine was regularly dropping on royal necks. The new French republican government “liberated” the papal territories of Avignon and the Comtat Venaissin. A plebiscite in 1791 annexed them into the French republic. Pope Pius VI was hung in effigy, an insufferable humiliation. The ponitff deployed papal mercenaries to reclaim the territory, but the French routed his army. His Holiness responded with an interdict on the French nation and a call for a levy to support a war on the French. Here is how he reportedly sold these action to Italians:“We promise plenary indulgences and eternal recompenses to the faithful who shall murder most of these ferocious French; we grant an entire amnesty to robbers, assassins, and parricides who shall redeem their crimes by fighting for religion; we give in advance our absolution to courageous women who, like Judith, shall abandon themselves to the Philistines and cut off their heads. … let all men and women plunge their hands in the blood of the French and taste the delights of this glorious holocaust.”[6]

The Romans reacted rabidly to the challenge. They attacked French officials in Rome and murdered Nicolas Jean Hugon de Basseville (or Bassville), who had served as secretary of the French legation to Naples. This was a mistake. The French republican government assigned a young Corsican named Napoleon Bonaparte to lead troops into Italy. They rapidly crossed the Alps and conquered the Piedmont and the Austrian empire’s holdings in northern Italy.[7] Someone evidently had removed the pages explaining the impossibility of rapid military movements from Bonaparte’s field manual. Before the pope could catch his breath, the French army was at his border. The pontiff begged for an armistice. He ceded Bologna, Ferrara, and the entire Romagna to France. He also handed over a large sum of money and many pieces of precious art. The negotiators for the French also demanded that he lift the interdict, terminate the Inquisition in Italy, and abolish castration. Pope Pius agreed to raise these issues in consistory, but he claimed that no pope could implement such changes on his own. If he convinced the French that he actually believed this, he deserved an Oscar. Having learned on the q.t. that the Austrian emperor was preparing to counterattack the French, the pope called for a crusade. Perhaps Sr. Mary Immaculata could somehow reconcile this with the armistice that he had just signed, but it must have looked suspicious at the time. Unfortunately, the pontiff’s correspondence with Emperor Francis was intercepted by Bonaparte’s sentries. Napoleon ordered his troops to march on Rome. The city’s defense was as pitiful as in 1527 when Pope Clement VII’s defenders had been brushed aside. The pope saw little choice but to agree to the terms of the Treaty of Tolentino, which ceded Avignon, the Comtat Venaissin, and the legations of Bologna, Ferrara, and the Romagna to France. Napoleon also installed a garrison in Ancona, a strategic port on the Adriatic.Shortly thereafter Pope Pius’s health suddenly deteriorated. His cardinals and his family, fearing the worst, diverted Church revenues into their private funds. Nothing remained to pay the pope’s debt to the French. When the pontiff recovered, he had to scramble to deal with this fiasco. He tried to force the clergy to help him raise money. In fact, however, many priests fomented rebellion among the people. Meanwhile, Napoleon ordered his brother Joseph[8] and General Duphot to prevent the Church from weaseling out of the compact.

The Romans ordinarily preferred to be governed by one of their own, even if he turned out to be a scoundrel. In this case, however, French calls for liberation of Italian political prisoners and termination of the Inquisition sounded awfully good. When spontaneous rebellion erupted against the papacy, the pope’s guards fired on the insurgents. General Duphot was killed on December 28, 1797. The pope refused to apologize.Joseph Bonaparte realized that events had spun out of control. He went north to get the French army. General Berthier led his troops down to Rome. The gates were thrown open not by the pope but by the Romans, who welcomed the French troops as liberators. Pope Pius retreated to the Vatican. The French refused to negotiate with him.

The Romans formed a provisional government. It deposed the pope, and convicted several cardinals and papal relatives of various crimes, confiscated their possessions, and imprisoned them. On February 20, 1798, Pope Pius himself was captured by the French and held first in Siena and then in a Carthusian monastery near Florence. The Romans soon saw through the French slogans and chafed under the reins of the occupation. Many even demanded that the pope – still a major source of revenue – be returned to the Holy See. Instead, the French took him on a forced march across the Alps to Valence, a town near the Swiss border south of Lyon. Before he died in this pitiable state of exile on August 29, 1799, Pope Pius VI issued one critically important decree. The next conclave, customarily held at the location of the pope’s death, was to be convened wherever the largest number of cardinals could conveniently assemble. Pope Pius’s last role, the long-suffering but steadfast papal martyr, was by far his best performance since his wall-smashing debut. Few mocked him in his last few stressful years.Pope Pius VI nearly surpassed the twenty-five-year pontificate traditionally attributed to St. Peter. He was within four months, and he was only eighty-two when he died. French mistreatment might have cost him the record. Excluding St. Peter, no pope in the first eighteen centuries and only one in each of the subsequent two centuries (with incomparably better hygiene and medical care) held the office longer.

The French and Pius VII It may have been the best of times for some Europeans, but New Year’s Day of 1800 was the worst of times for the papacy. Many people considered the institution finished.[9] Bonaparte, who had completed his Egyptian campaign and returned to France as First Consul, insisted that the pope be buried in French soil. Because no cardinals were near Valence, the conclave was held on the island of San Giorgio in Venice, which was then in the friendlier hands of Emperor Francis of Austria. The cardinals elected Cardinal Chiaramonti of Cesena, a very tactful and amiable fellow who during the previous turbulent decade had managed to avoid taking political stands. Although he bore no resemblance to his haughty predecessor, he boldly took the name of Pius VII. On March 21, 1800, he was crowned with a papier-mâché tiara. French troops had seized his predecessor’s jewel-encrusted head-warmer, and no one would spring for a new one.

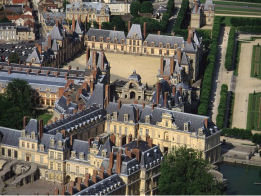

The Austrian emperor feared that Chiaramonti was not tough enough for the job. He tried to persuade him to set up shop in Vienna. When that failed, he maneuvered to keep the pope in Venice, an imperial stronghold. Pope Pius VII, however, departed for Rome, and he finally arrived on July 3, 1800. While the pope was inching his way south from Venice, Bonaparte had blitzed through Italy again. He defeated the Austrians at the battle of Marengo on June 14. When the pope reached Rome, most of Italy was controlled by Napoleon’s commanders, not the Bourbons or Hapsburgs. Seldom has a pope-elect declined the honor. If ever a papabile should have ever entertained second thoughts about accepting the tiara, it was in 1800. If an easy-going fellow like Pope Pius VII had foreseen that he would be dealing with Napoleon Bonaparte for fourteen years, he probably would have stayed in Cesena. His talents were just not suited to the challenge. Bonaparte decided to declare himself emperor (of France, for the nonce), and he wanted the pope on hand for his coronation. A papal presence could add legitimacy to his audacious claim. In 1804 he persuaded Pope Pius to journey to Paris for the ceremony in the Cathedral of Notre Dame. Napoleon returned the tiara that had been confiscated when his men took Pope Pius VI prisoner and offered other incentives as well. Just before the imperial coronation Pope Pius VII himself administered the sacrament of matrimony to Napoleon and Josephine Bonaparte. Their previous nuptials had been a strictly civil function. The putative purpose of the pope’s trip had been to allow him to set the crown on the new emperor’s head. However, Napoleon audibled a trick play at the line of scrimmage. He abruptly grabbed the crown and placed it on his own head. He then crowned Josephine empress. The pope just gaped in astonishment. He had been demoted from supreme pontiff to just another bystander witnessing Napoleon’s glory. Napoleon urged the pope to stay in France, but Pius eventually returned to Rome. Over the next few years the emperor gradually removed every scintilla of authority and dignity that the papacy had amassed over the centuries. The pope’s territories were stripped from him one by one until 1808, when Napoleon seized Rome, even Castel Sant’Angelo. On July 5 a lieutenant captured the pope himself. He was held for three years at Savona and spent the next three years as a prisoner at Fontainebleau, where he was browbeaten into signing a humiliating concordat. Bonaparte’s military downfall, however, signaled the papacy’s revival. The French emperor allowed the pope to return to Rome on May 24, 1814. At his first opportunity Pius repudiated the concordat. Napoleon was eventually overthrown and exiled to Elba. The Congress of Vienna returned to the Papal States its previous possessions except for Avignon and the Comtat Venaissin.Then Napoleon returned in triumph! In panic the pontiff fled to Genoa for a short time. Bonaparte was eventually recaptured, the Bourbons resumed occupation of their thrones, and the Pope returned to Rome. The restored King of France, Louis XVIII, also gave back most of the artwork that the pope had ceded to Napoleon’s France.

During this horrific period Church finances had deteriorated disastrously. Despondent from a decade of non-stop humiliation, the pope failed to devise any novel approaches; loans and relic sales were the best that he could muster. Fortunately, Madame Letitia, Napoleon Bonaparte’s mother, had relocated to Rome. The fates obviously love irony; she became a reliable source of financing for the Church’s recovery.

Madame Letitia … now that she is old (as is generally the case), turned devotee, and is surrounded by hypocrites and impostors, who, under the mask of sanctity, deceive and plunder her. Her antechambers are always full of priests, and her closet and bedroom are crowded with relics. … She might, if she chose, establish a Catholic museum and furnish it with a more curious collection, in its sort, than any of our museums contain. Of all the saints in our calendar, there is not one of any notoriety who has not supplied her with a finger, a toe, or some other part; or with a piece of a shirt, a handkerchief, a sandal, or a winding-sheet. Even a pair of breeches, said to have belonged to St. Mathurin, whom many think was a sans-coulotte, obtain her adoration on certain occasions. … She has, in her will, bequeathed to the pope all her relics, together with 879 prayer-books and 446 Bibles, either in manuscript form or in different editions.[10]

The cardinals returned to their sinecures. Item number one on everyone’s agenda was the Jesuits. On August 7, 1814, Pope Pius reinstated the Society of Jesus. Almost immediately well-heeled Jesuits appeared, ready to endow academies in France and Italy. Over the next decade artists flocked to Rome, and it became a favorite location for royal visits. Thankfully the genie was back in the bottle. The kings sat securely on their thrones, and faithful European Christians had finally banished from their heads that ridiculous notion of democratic government!Pope Pius VII survived until August 20, 1823. Throughout his twenty-three-year pontificate he was more spectator than player. He outlived Napoleon by two years, even though he was older at his investiture in 1800 than Napoleon was when he died.

The Church’s man of action in the Napoleonic era was Cardinal Ercole Consalvi,[11] Pope Pius’s Secretary of State. When Napoleon released the pope, Consalvi negotiated the restoration of his territories. He also worked to establish an efficient government in the Papal States, but he was thwarted at every turn by his fellow prelates, who were intent on reestablishing their own power bases, and by freethinkers, most notably the Carbonari, a revolutionary secret society organized along the lines of the Freemasons. European life was trying during the post-Napoleonic period. The summer of 1816 was especially difficult. Because of the stupendous eruption of the volcano Tamboro in Indonesia, Europe was bitterly cold. Crop failures there led to widespread starvation. At least 200,000 people died of hunger and a typhus epidemic in one year. Italy suffered less than Switzerland, the low countries, and the British Isles.The Throwback Papacies

In the conclave of 1823 Consalvi could not prevent his fellow cardinals from electing Cardinal Annibale Francesco Clemente Melchiore Girolamo Nicola Sermattei della Genga, whom Consalvi had sacked nine years earlier, as Pope Leo XII. The name was a peculiar selection because the only two Leos since 1054 belonged to Florence’s defunct Medici family. The new pope’s tall svelte figure suited the role of supreme pontiff, but he was not exactly a people person. Maybe his poor health begat his perpetually sour mood. When elected, he reportedly told the cardinals, “Don’t insist. You have elected a cadaver.”[12] Among other ailments he suffered horrendously from hemorrhoids.[13] His six-year pontificate did not lack highlights:

- He immediately gave Cardinal Consalvi the boot.

- He ordered the imprisonment of anyone who played games on Sundays or feast days.

- The prison constructed for him in 1827 in Rome is now the Crime Museum.

- All works of art with nudity were removed from public view.

- In courts of law in the Papal States – civil as well as ecclesiastical – the Italian language was replaced with good old Latin.

- Pope Leo repaired the walls of the Roman ghetto and reinstituted the laws limiting the dress and behavior of Jews. He even rescinded their property rights.

- He rebuilt the Jewish ghetto in Ancona.

- Jews were forced to listen to sermons every Sunday.

- Pope Leo shot birds in the Vatican Gardens.

- Encores and ovations were banned in theaters.

- Actors were not allowed to ad lib on stage.

- Walking too closely behind a woman was declared criminal.

- All bars were closed, but alcohol could be purchased on the street. Tavern owners sold their wares through the gates.

Pope Leo continued the policy of condemning the Carbonari and other secret Italian sects. He excommunicated their members, as had Pius VII before him. He then established a police state in papal territories. On August 31, 1825, Cardinal Rivarola, the pope’s legate in the Romagna, condemned 508 people without trial. Rivarola’s successor, Monsignor Invernizzi, hired a network of spies. Citizens were provided monetary incentives to turn in their neighbors. Eventually, “the prisons were so full that old convents were fitted up to receive the numbers that were condemned.”[14] What might have been a joyful period in which Italians finally cast off the yokes of the Hapsburgs, the Spanish, the Bourbons, and Bonaparte became a Kafkaesque nightmare of secrecy and distrust. Leo’s pontificate has been characterized as “a grotesque caricature of tyranny.”[15]

Pope Leo did not believe Ricardo. The pope’s confiscatory tariff on imported good that resulted in the impoverishment of the citizenry and eventually led to malnutrition and even famine. The price of grain rose to five times the level of neighboring regions. Nobody calls him a great pope, but Leo XII was not an insensitive monster. He finally removed all of Galileo’s works from the Index. Some have claimed that in 1829 the pontiff, who died only forty-one days into that year, announced that anyone who accepted a vaccination against smallpox was no longer a child of God because vaccinations impinged on God’s sovereignty over life and death. This calumny appears to have resulted from confusion. Cardinal Consalvi had previously made vaccination a condition for receipt of relief funds; Pope Leo removed that restriction. He apparently did make a caustic remark about syphilis being just desserts for illicit sexual activity, and he banned the use of condoms. Pope Leo died in 1829. He was followed by Francesco Saverio Castiglione, a much more easy-going fellow whose health was even worse than his predecessor’s. After taking the name of Pius VIII, he turned the affairs of the Church over to his Secretary of State, Cardinal Albani. The pair only held office for twenty months.In December of 1830 popular uprisings seemed inevitable. Although the cardinals in conclave received ample warning of the danger of a power vacuum, the usual issues hobbled them – parties with fixed agendas, self-serving motives, and threatened vetoes from various rulers. The man who emerged after seven weeks was Bartolomeo Cappellari, a Camaldulian monk who had never been a bishop. The Church needed a sophisticated and creative leader to face modern complexities – advances in science, medicine, and engineering as well as many challenging philosophical ideas. Here is what it got:

The new Pontiff was tall and lusty, with a coarse rubicund countenance; the typical gormandizing, bibulous, hoydenish monk of the irreverent French novelist come to life in the nineteenth century. He lacked both poise and dignity, and his favorite recreation consisted in playing blind-man's-bluff with the least aged of the cardinals. So roughly did he treat his unfortunate playfellows that in his exuberance he knocked down Cardinal Soglia one fine day, the shock being so violent that the victim almost died of it. In another mood he would order all the palace servants to be assembled in the courtyard and from a window would throw down handfuls of money to them, laughing till his sides ached to watch the ensuing scrum.[16]

Pope Gregory XVI took the throne on Groundhog Day of 1831. Within days serious rebellions erupted throughout the Papal States. Cardinal Benvenuti, who was sent to deal with them, was captured. A desperate Cardinal Bernetti called in the Austrian army to suppress the revolt. The Austrian troops crushed the movement temporarily, but subsequent uprisings required additional interventions. Eventually the Austrians insisted on Bernetti’s ouster, and the pope replaced him with Cardinal Lambruschini, who convinced the pope to ban railroads and artificial gas lighting[17] in the Papal States! To cope with the secret societies, Lambruschini unleashed a network of undercover spies and set up hard-line courts. The prisons were soon packed to the rafters. Squelching the uprisings forced Pope Gregory to borrow a great deal of money. He turned to the Rothschilds, who were willing lenders. When he awarded the Order of St. George to Carl Rothschild, the pontiff was criticized both for contradicting his own frequent calls for complete separation of Christians and Jews and for promoting usury. The loans allowed the pope to take several very expensive tours of his own territories. Meanwhile, Lambruschini dealt with the rebels. His policies resulted in many executions and the incarceration of staggering numbers. If he thought that this would eliminate the problems, he understood little of human nature. Pope Gregory’s outlook toward modern ideas was formulated in his encyclical “Mirari Vos” of 1832. This document, written less than two centuries ago, forcefully argued against free speech and the free press. It recommended mindless obedience by Christians to every dictate however immoral or stupid issued by anyone wearing a crown. The pontiff even stressed a Christian’s duty to take up arms on behalf of his prince, regardless of the cause. The pope always found time for Clementina Verdesi, the wife of Gaetanino Moroni, who made a fortune in real estate during this pontificate. She became known as “puttana santissima.” Gregory also took good care of his own relatives and even exempted them from inheritance taxes.[18]Cancer claimed Pope Gregory in 1846. At his death the clubhouse was firmly in the papacy’s control, but the gophers seemed poised to take over the golf course.

[1] According to Cormenin, he “led the life of a Sybarite, fulfilling none of his pontifical functions, confining himself to the celebration of mass in his oratory, or being enthroned for an hour at a solemn audience, and passing the rest of his time in getting drunk with his mistresses and his minions.” Op. cit., Vol II, p. 400. The original source of many of these and other charges is Giuseppe Gorani’s Mémoirs secrets et critiques des cours, des gouvernemens, et des moures des principaux états de L’Italia, a book published in 1794 that was on the last published Index. On the other hand, de Bernis called Braschi “morally pure.” Frederik Kristian Nielsen, The History of the Papacy in the XIXth Century, translated under the direction of Arthur James Mason, John Murray, 1906, Vol. I, p. 167.

[2] Cormenin, who was born during this papacy, made these astounding claims: 1) the pope fathered both of these young men; 2) he arranged for one, Louis, to marry a young lady named Dona Costanza, who was also allegedly a product of his loins; 3) the pope claimed his daughter/daughter-in-law as his mistress! Op. cit., Vol. II, p. 403

[3] Many workers died, probably from malaria. “The pope, to replace the voids which death made among the workmen, carried off forcibly laborers from the adjoining country and decimated the population.” Ibid., p. 402. Mussolini completed the project in the 1930’s.

[4] The teen-aged Mozart gave his first Lenten Concert in Vienna while the pope was there, but the pontiff missed it. In fact, Pope Pius VI hardly ever stepped out except on official business. He even stayed in Rome in the Quirinal Palace during Ferragosto.

[5] Annual Register, 1799, p. 337. These are the devil’s words in Matthew 4:3. Jesus’s response in that text is that man does not live by bread alone.

[6] D. M. Bennett, Champions of the Church: Their Crimes and Persecutions, New York, 1878, p. 942. His source may also be Gorani.

[7] Napoleon used the refectory of Milan’s church of Santa Maria delle Grazie as a stable for his horses. One of its wall contains Leonardo da Vinci’s magnificent Il Cenacolo, The Last Supper. A mare with ties to the Priory of Sion deciphered the secret message therein and tried in vain to explain the symbolism to her handlers through stamping and whinnying.

[8] Joseph Bonaparte later had unsuccessful careers as the King of Naples and Sicily (1806-1808) and the King of Spain (1808-1813). He moved to the United States in 1817, and he allegedly encountered the Jersey Devil in the Pine Barrens in 1835.

[9] The Annual Register of 1799 erroneously predicted that there would probably never be another Jubilee Year (p. 341).

[10] Anonymous, Memoirs of the Court of St. Cloud, Kessinger Publishing, 2004, p. 75.

[11] The French insisted on Consalvi’s removal. Napoleon once even ordered his execution. Fortunately, he quickly retracted the order and instead insisted that Consalvi and a dozen other cardinals wear black robes. The group became known as the “black cardinals.” Black was the new red!

[12] Rendina, op. cit., p. 755.

[13] Maybe he chose the name Leo as a tribute to Pope Leo X’s condition.

[14] “Rome and the Italian Revolution,” in The North British Review, Vol. XIV, 1870, p. 327.

[15] Owen Chadwick, The Popes and European Revolution, Oxford University Press, 1981, p. 569.

[16] Pirie, op. cit., p. 320.

[17] London’s Pall Mall was lit back in 1807.

[18] Rendina, op. cit., p. 763.

| |

| |

Bankable Bar Bets

$ Pope Pius VI made a month-long visit to the palace of the emperor in Vienna. He was not invited.

$ Pope Pius VI declared that he lacked the authority to repeal his own interdict, end the Inquisition in Italy, and ban castration.

$ There was no pope in Rome at the beginning of the Jubilee year of 1800. The celebration never took place.

$ Pope Pius VII’s coronation featured a papier-mâché tiara.

$ Napoleon Bonaparte kept Pope Pius VII a prisoner for over six years.

$ Napoleon ordered a dozen cardinals to wear black instead of red.

$ Napoleon’s mother, Madame Letitia, helped finance the recovery of the papacy after her son was exiled to St. Helena.

$ Madame Letitia Bonaparte reportedly owned 446 bibles, 889 prayer books, and countless relics, including St. Mathurin’s underwear.

$ At least 200,000 Europeans died of hunger and typhus in 1816.

$ Pope Leo XII hunted birds in the Vatican gardens with a rifle.

$ Pope Leo XII forbade ovations and encores in Roman theaters. He also banned ad libs on stage.

$ Pope Leo XII made it a crime punishable by imprisonment to play games on Sundays and feast days.

$ Pope Gregory XVI banned the railroads and gas lighting in the Papal States.