Chapter 21: White Popes and Black

Back to Basics

Thirteen years of moral exactitude and fiscal austerity under Pope Innocent XI all but ensured that the next pontiff would have a short life expectancy and would return revelry to Rome. Pietro Vito Ottoboni became Pope Alexander VIII on October 5, 1689, and acted as if his doctor had given him a month to live. He actually lasted a year and a half, and he squeezed the most out of each minute. He revoked all his predecessor’s restrictions on the cardinals, and he distributed favors, cash, and benefices to his family in the great pontifical tradition. His fourteen cardinals included two nephews and a grand-nephew. Pope Alexander purchased Queen Christina’s impressive collection of manuscripts for the Vatican Library. He also lowered taxes and negated Innocent XI’s edicts that were designed to uplift Roman morality. Theaters were reopened. Alexander quickly became quite a popular pope.He enforced Pope Innocent’s ban on diplomatic asylum in Rome, but, in order to secure the French cardinals’ votes in conclave, he conceded King Louis XIV’s right to appoint French prelates. In return the Sun King donated Avignon to the papacy. On his deathbed, however, the pope unexpectedly condemned both the actions of the Gallican clergy and the droit de régale.

The pendulum swung back in the five-month conclave of 1691. Cardinal Altieri somehow wormed his way into the good graces of King Louis, who had been stunned by Pope Alexander’s last-minute reversals. Altieri proposed Antonio Pignatelli, a mild-mannered inoffensive old cardinal who supported Louis’s droit de régale and adroitly convinced the cardinals from Spain and the empire of Pignatelli’s merits. The main selling points were that he was a Neapolitan subject of Spain, and his lack of nephews would likely insure plenty of benefices to spread around. Although Altieri’s entire career was based on a previous pontiff’s lack of relatives, he delivered this argument with a straight face, and Pignatelli became Pope Innocent XII.

Pignatelli had been named a cardinal by the last reforming pontiff, Innocent XI. He not only named himself after his patron, but he followed in his footsteps by promptly banning nepotism once and for all. His bull “Romanum Decet Pontificem” allowed popes to make cardinals of only one relative. All future popes would be forced to swear that estates, offices, and revenues could not be bestowed on relatives. Papal nepotism had endured for sixteen and a half centuries, but Pope Innocent eradicated it.Innocent must have been extremely persuasive. King Louis XIV, who turned sixty during this pontificate, agreed to repeal the Declaration of the French Clergy and renounce the droit de régale. The pontiff also induced King Charles II of Spain to sign a will in support of the Bourbon claim to the Spanish throne.

Pope Innocent donated considerable sums to the poor. Nevertheless, because he curtailed the largess bestowed on cardinals, family members, and the politically connected, the Holy See’s finances were in the black at his death in 1700.

Pope Btfsplk II

By the late seventeenth century perspicacious Europeans could sense the impending collapse of the Spanish empire. King Charles II, the only son of Philip IV and Mariana of Austria, had been sickly[1] from birth. He was too retarded even to receive schooling. Few expected him to survive childhood, but 1700 marked his thirty-sixth birthday. Even as an adult he could barely walk and talk. The last year of the unchallenged ruler of Spain’s colossal worldwide holdings was spent in paralysis. Charles had no heirs and no chance of producing one. A great deal therefore depended upon the timing of his death. God, through the voice of His Vicar, Pope Innocent XII, had convinced Charles to name Philippe de Bourbon, who was the Duc d’Anjou and King Louis XIV’s grandson, as his heir. Imagine everyone’s surprise when Pope Innocent died before the inert Spanish monarch. Europe’s attentions focused on the conclave of 1700. With the Spanish empire inevitably falling into new hands, the new pope could probably exert considerable influence on the distribution of Spain’s prized possessions. The French feared lest the new pontiff change what was left of Charles’s mind in favor of another claimant. One way to prevent this was to delay the papal election until King Charles had succumbed. The French cardinals were well-schooled in the subtleties of papal selection and knew how to prolong the conclave. By the time that the leader of the French delegation, Cardinal Noaille, sashayed into Rome a few weeks after the conclave began, King Charles had died. Philippe arrived in Madrid just as the cardinals learned of Charles’s passing. The coronation of the Bourbon duke as King Philip V was a fait accompli.

Graneri in a letter to the Duke of Savoy gives another explanation of his strange behavior. He says that Albani, having solemnly sworn to renounce nepotism and seeing no loophole of escape from the consequences of his oath, became panic-stricken at the idea of the quarrels and recriminations awaiting him in his family circle. He was burdened with several ambitious nephews and a sister-in-law who dominated him as Donna Olympia had dominated Innocent X. Being a determined and spirited woman, she was likely to make a vigorous attempt to induce him to break his pledge, and he shrank from the encounter.[2]

Hysteria incapacitated Cardinal Albani on his election day. The following day he still refused all human contact. On the third day he asked a committee of learned theologians to enumerate his legal options. They counseled him that it was his duty to accept the tiara, but it would not be sinful to reject it. He wept at this finding, but, then again, tears often stained his face. He reluctantly consented to taking the throne as Pope Clement XI.

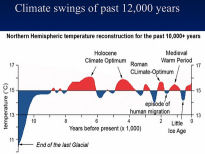

In 1700 the world awaiting this timorous new pope was at a crossroads. European countries had by then removed the liquid assets of most far-flung colonies. Many still boasted vast natural resources, but most readily available gold and silver had been expropriated. Moreover, some colonists were growing a little uppity. In Europe the Little Ice Age neared its peak, glaciers threatened civilized areas. Crop failures led to starvation, and ruinous precipitation patterns devastated countries where traditional crops were still feasible. At the time no one called the new fellow on St. Peter’s throne Pope Btfsplk II, but it would have been appropriate. His long pontificate was the most disastrous since that of his namesake, Clement VII,[3] during whose reign the sack of Rome was only one of many disasters. The early eighteenth century was similarly fraught with peril. The Church needed a conjurer with a repertoire of stunning effects, impeccable timing, and smooth patter. Pope Clement was an upstanding intelligent man with a friendly manner and a good heart. In another age he might have made a great pope, but in this era when all the marbles were on the table, he was all wrong. Bad news literally began pouring in to Rome almost as soon as the conclave concluded. The Tiber overflowed its banks in the city. In 1703 a much worse flood caused very serious damage, and it was followed in short order by an earthquake that caused two columns in the Colosseum to collapse, and many huge blocks crashed to the earth.In the 1600’s the Church had established missions nearly everywhere. Some of these ministries had achieved startling successes. The black-robed Jesuits had converted throngs of Chinese. The Jesuits mastered the language and familiarized themselves with important elements of Chinese culture. Despite many setbacks, their determined efforts had produced a sizeable Chinese Catholic population. The Jesuits had also cultivated excellent relations with the Chinese government. The emperor even employed them in critical scientific and artistic posts. Ferdinand Verbiest, a Flemish Jesuit, actually supervised the pouring of 132 cannons for the imperial army.

However, the word trickled back to Rome – mostly via Dominican monks – that Chinese rituals were inconsistent with those practiced in Europe. The Jesuits allowed their converts to venerate their ancestors, and they even integrated Confucianism into the liturgy. Pope Clement assigned Charles Maillard de Tournon the fanciful title of Patriarch of Antioch and dispatched him to investigate the “Chinese Rites.” De Tournon’s testy meeting with the emperor in 1706 resulted in an imperial decree mandating the use of the Chinese Rites. De Tournon, claiming to act on the pope’s behalf, prohibited them. The emperor then imprisoned de Tournon in Macao, where he died[4] a few years later.

The pope’s bull “Ex Illa Die,” effectively prohibited the Chinese Rites. China-bound missionaries were required to forswear them. In 1720 the pope allotted to Carlo Ambrogio Mezzabarba the equally silly title of Patriarch of Alexandria and sent him to promulgate his decree in China. From the emperor’s perspective, the pope was an ignorant, insensitive, and insulting meddler. The emperor forbade the teaching of Christianity in China! However, Mezzabarba, unlike de Tournon, was a skilled negotiator. He agreed to concessions that might have served as a basis for a constructive relationship, but they were ultimately vetoed by Rome. The pope’s bull set in motion the permanent and catastrophic[5] loss of China – a quarter of the world’s population – to the Church. There probably was a religious aspect to the Confucianism and ancestor veneration in the Chinese Rites, but in other missions the Roman Church had eagerly co-opted religious customs of new converts. This syncretism was in fact a prominent issue in the great schism. Christianity paid a high price for the strictness of Pope Clement and his successors.Reshuffling Europe

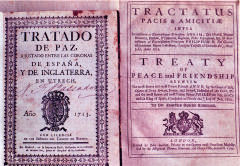

Charles II’s death left the worldwide Spanish dominion available for the taking, and Philip immediately took the throne. Could Europe really be expected to permit the family of that obnoxious little peacock, King Louis XIV, to seize an empire spanning four continents? Pope Clement was particularly concerned because none of the powers involved – not even France – could match the papal sympathies of the Spanish. He quickly extended congratulations to Philip V, the new ruler of the Papal States’ heavily armed neighbor on both the north and the south. What else could he do? The pope’s endorsement infuriated Emperor Leopold of Austria, who coveted for his son the Spanish crown or at least some Spanish territories. The emperor boasted a pretty strong claim through his Hapsburg lineage. The claim of a third candidate, the Elector of Bavaria, Joseph Ferdinand, had been supported by England and the Netherlands. In fact, Charles II had even named Joseph Ferdinand as his heir in 1698. Unfortunately, Joseph Ferdinand expired before Charles. King Louis XIV made the first move. Rather than negotiate the distribution of the Spanish territories, he recognized his grandson Philip as king of the entire Spanish dominion. When he cut off England and the Netherlands from Spanish trade, he provoked the long War of the Spanish Succession. Spain and France were opposed by the Holy Roman Empire, the Netherlands, England, and Savoy. For the papacy it was worse than being caught between a rock and a hard place; the rocks were moving. Part of the war played out in Italy. The Savoy family had allied its small kingdom in northwest Italy with the empire. The Savoy princes quickly invaded the Duchy of Milan. The French reacted strongly, but somehow the mouse held off the lion, and Savoy later even boldly essayed an unsuccessful invasion of France. The papacy stayed out of the war, but Pope Clement’s maneuvers left the Church in the worst possible position. His endorsement of the Bourbon claimant outraged the empire and its allies. On the other hand, his bull “Unigenitus” of 1713, which railed against the “Gallican” approach to Catholicism, so disturbed the French Church that priests would not read it to their congregations. Other papal stratagems worsened matters. So pressed were the Papal States by incursions from Savoy and the empire that the pope reversed course and recognized the Archduke as the King of Spain. This action alienated King Louis XIV at a critical juncture. For more than a decade the war chewed up young men all over the western half of the continent. In 1713 the conflict was terminated by the Treaty of Utrecht, followed in 1714 by the treaties of Rastatt and Baden. The negotiators did not solicit Pope Clement’s counsel, and he suddenly found himself with new neighbors. The previously sleepy kingdom of Savoy had become the new ruler of Sicily and much of the former Duchy of Milan. Emperor Charles VI was ceded the Kingdom of Naples, Sardinia, and the rest of the Duchy of Milan. The pope’s vociferous protests against changes in the balance of power in Italy fell on deaf ears. The duchies of Parma and Piacenza, which before the treaties were still held by the Farnese family, devolved to Spanish control on the death of the reigning duke. Thereafter the duchies served as shuttlecocks for the major powers for two centuries, a condition emblematic of the papacy’s situation. The centuries of relative stability in Italy were over. No holding was secure. Sicily and Sardinia, for example, were returned to Spain in 1718. Only two years later Austria seized Sicily, but the Spaniards were back within fifteen years. Pope Clement’s pontificate lasted for more than twenty years. Not every note was sour. During the middle of the War of the Spanish Succession, the Ottomans invaded Europe. The emperor and the incomparable Prince Eugene of Savoy – with monetary assistance from the papacy – repelled them in the decisive battle in Hungary at Temesvár. However, even this endeavor proved an embarrassment. The pope had persuaded King Philip of Spain to raise a fleet to sail against the Turks, and he subsidized the effort heavily. However, to the pope’s chagrin, his treacherous minister, Cardinal Alberoni, diverted the armada to Sardinia. Pope Clement still hoped for the Stuart family’s return to the English throne to re-establish Catholicism in Great Britain. A revolution in 1688 had deposed the fourth Stuart king, James II, but the Church never recognized his successors, William and Mary, a Protestant couple from Hanover. James III, whose godfather was Pope Innocent XI, embodied the Stuart claim. Pope Clement provided him with suitable lodging in Avignon and Urbino. His Holiness even arranged James’s marriage to Clementina Sobieska. The happy couple settled in Rome at the Palazzo Muti and maintained a regal lifestyle thanks to generous subsidies from the pope and Louis XIV.Tradition held that no pontificate could surpass the twenty-five-year term attributed to St. Peter. Pope Clement’s twenty-one-year stint was the first legitimate[6] challenge to the legend since Pope Alexander III, who had died from writer’s cramp 540 years earlier. Since the ill-starred Clement was only seventy-one at his death, he might have easily broken the record had not tranquility unexpectedly overrun Europe.

Worse and Worser

After such a long troubled pontificate, the smart money in the banchi in 1721 was on old and sickly men. Michelangelo de’ Conti, however, was only sixty-six when he was elected in a notably tame conclave. France and Spain were finally allied, and the Austrians had not yet figured out the subtleties of the papal selection process. They tried to buy votes – of respectable cardinals, mind you – with gem-inlaid rings and other baubles. Conti understood where his bread would be buttered and agreed to the French conditions before selecting the name Innocent XIII. He broke precedent by making good on promises made in the conclave. He is remembered as a prodigious sleeper with three dubious accomplishments: 1. He investigated Cardinal Alberoni’s treacherous behavior and somehow saw fit to clear him of the charges leveled by his predecessor, Pope Clement.2. He continued the generous stipend allotted to his neighbor, James III, the pretender to the English throne.

3. He enforced the prohibition of the Chinese Rites by prohibiting the Jesuits from ordaining any new priests into their order!

When Pope Innocent died in 1724, the cardinals turned to the Orsini family, one of the most powerful in Rome. It had produced a stunning number of influential cardinals but no popes in many centuries. Pietro Francesco Orsini, a Dominican, had for thirty-eight years been Bishop of Benevento, a papal enclave surrounded by the Kingdom of Naples. As a “Zelante,” he insisted that the pope should concentrate his attention on spiritual matters.In fact, his Orsini lineage probably had little effect on the election. His trusted associate, Niccolò Coscia, had arranged deals in his boss’s name with the conclave’s movers and shakers. Coscia convinced them that if Orsini were elected, he, Coscia, would be in a position to follow through on his commitments. This sounded good to enough of the bitterly divided cardinals.

Orsini selected the name Benedict XIV. Uh, better make that Benedict XIII. Someone had to explain to the new pontiff that Pedro de Luna, the first Benedict XIII, was considered schismatic. It was not debatable; the name of de Luna’s predecessor in the Avignon obedience, Clement VII, had been reused two hundred years earlier by Julius de’ Medici. Whether Orsini’s mistake was due to ignorance or triskaidekaphobia is moot.

Pope Benedict immediately elevated Coscia to the rank of cardinal and assigned nearly all decisions to his compaesano. Coscia summoned his cronies to Rome to begin diverting as much wealth to Benevento as physically possible. They tried to disguise their embezzlements, but the scope of the operation rendered subterfuge infeasible. Romans attempting to complain to the pontiff could never get his ear.

Pope Benedict took a few memorable measures in his own right.

- He allowed the Jesuits to resume ordinations.

- He kept up the subsidy to James III, the pretender to the English throne.

- He banned wigs.

- He repealed the papal ban on snuff, which he himself used regularly.

- He issued several decrees on how priests should dress. Casual Friday was out.

- His elimination of the lottery and banning of games of chance torpedoed his standing in Rome.

- He promised that anyone who on his deathbed voiced the words “Blessed be Jesus Christ” would cause his time in purgatory to be reduced by two thousand years. His theological training evidently did not include the undeniable fact that making a good confession would eliminate the trip to purgatory entirely.

- His attempt to promote the cult of St. Gregory VII throughout Europe provoked the ire of the ruling class. After all, Gregory had forced Emperor Henry IV to stand for days in freezing weather with no covering for either his head or his feet.

When Pope Benedict died in 1730, Cardinal Coscia needed to make himself scarce, but he was inconveniently laid up with the gout. Coscia allegedly evaded the Romans’ wrath by having himself removed from his palazzo in a coffin. Nevertheless, he somehow wormed his way back into Rome to participate in the ensuing conclave.

The papal election of 1730 focused on the Duchy of Florence, then ruled by Gian Gastone de’ Medici, the last (and probably least) of the Medici line, a bedridden Howard Hughes type – including the hair and nails – addicted to alcohol, tobacco, and God knows what else. No one gave him long to live, and he had no heirs. None were expected either; his wife resided in Bohemia, and the duke’s proclivities ran to young boys. Several European powers hoped to add the Medicis’ territories to their portfolio of colonies, and the conclave seemed an ideal opportunity to advance their claims. Attention was therefore drawn to Cardinal Lorenzo Corsini, the seventy-eight-year old Florentine noble, in whose veins coursed “the best blood of Florence.”[7] He belonged to the Zelanti, but he was not considered as fanatical as Benedict XIII. Furthermore, Corsini’s ambitious young nephew Neri seemed to understand the unwritten rules. Once the notion of a Florentine pope had surfaced, the cardinal’s election was virtually assured. Neri greased the wheels using the reliable trio of cash, promises, and women, and Cardinal Corsini became Pope Clement XII. The pope awarded Neri a cardinal’s hat and placed the day-to-day administration of Church affairs in his hands. It was just as well. The pope’s blood may have been outstanding, but the rest of his body was a wreck. He was nearly blind and was bed-ridden for almost his entire ten-year pontificate.One of the new pope’s – or probably Neri’s – first moves was to dispose of Niccolò Coscia. A tribunal found him guilty of embezzling Church funds and cast him into a cell in Castel Sant’Angelo, where he was left to rot for ten years. He was excommunicated and forced to pay a large fine. However, there is a long tradition of leniency toward cardinals. No matter what the offense, cardinals are almost never voted off of the island.[8] As Pope Clement’s health deteriorated, his own relatives urged clemency for the errant cardinal from Benevento. Coscia was released from prison, and he attended the conclave following the pontiff’s death in 1740.

Here are a few highlights from Clement’s decade-long pontificate:- A portion of the money stolen by the Benevento clan was recovered and spent on the Trevi Fountain and other public works projects in the Papal States.

- The pontiff’s popularity soared when he reinstated the lottery in Rome.

- Clement’s 1738 bull “In Eminenti Apostolatus Specula” outlawed Freemasonry, excommunicated all Masons, and made membership a capital crime. The wording of the document was extremely peculiar: “Hence, the Pontiff, for the sake of the peace and safety of civil Governments, and the spiritual safety of souls, and to prevent these men from plundering the House like thieves, laying waste the Vineyard like wolves, perverting the minds of the incautious, and shooting down innocent people from their hiding places, pronounces the grave sentence of major excommunication against these ‘enemies of the common-weal.’” George Washington, Ben Franklin, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart ran with these wolves.

- The pontiff’s determined effort to end the schism with the Greeks failed, but at least relations improved.

- Parma and Piacenza were lost to the Papal State. Florence passed into control of the Hapsburg empire after its Grand Duke died in 1737.

- As a reward for mastering his multiplication tables, Pope Clement named the eight-year-old Luis Antonio Jaime de Borbón y Farnesio, Royal Infant of Spain, to the Sacred College of Cardinals.

No Bologna in This Papacy

Prospero Lambertini, who was chosen on August 17, 1740, after a six-month long conclave, makes a fascinating study. In some ways Benedict XIV was the most modern of pontiffs; in others he was a throwback. He was a real pope’s pope. He enjoyed a reputation as a scholar, a tireless writer, and a very likeable guy. He was sixty-four when elected, and his health was fine. He would never have considered turning the papacy over to a scheming nephew or one of his posse. In fact, he immediately ordered his relatives in Bologna to stay there. He set up impartial committees to locate qualified men for open positions. Each group drew up a list of the people whom they had vetted, and Benedict personally picked the best man for each post.Pope Benedict’s style was decidedly hands-on. He cleaned up the list of saints and martyrs in the canon. He discoursed at length on the nature of sainthood and what criteria the Church should use in the canonization process. He wrote an incredible volume of material specifying the forms of various religious practices and also published, according to The Catholic Encyclopedia, “numerous works on the rites of the Greeks and Orientals; Bulls and Briefs on the celebration of the octave of the Holy Apostles, against the use of superstitious images, on the blessing of the pallium, against profane music in churches, on the golden rose[9], etc.”[10]

The bombast and metaphor prevalent in many papal bulls renders them difficult to read and interpret. By contrast, Pope Benedict’s writings are startlingly clear. His decree on “mixed marriages” (in which one spouse is Catholic and the other is not) is still the basis for Church practice. In his eighteen-year pontificate Benedict issued a very large number of bulls, briefs, and encyclicals touching on nearly every aspect of faith and morals. Subsequent pontiffs have probably wished that Benedict’s writing had equivocated a little. For example, his bull “Vix Pervenit” clarified the serious sin of usury. Pope Benedict applied the term to any loan for which interest was charged. He expressly prohibited obfuscatory terminology for interest. This short, clear, and direct bull has never been countermanded by any papal decree.

We have not bothered Sr. Mary Immaculata for some time, but the Church’s approach to usury is difficult for a layman to grasp. Let’s amble over to the convent and get an explanation from an expert. “S’ter, if the Bible prohibits usury, and Pope Benedict said that charging interest on loans was a sin, aren’t banks sinful? Are Catholics allowed to use banks? I think my parents have a bank account; should I tell them to close it?”“Those are good questions. You should write a composition on this subject, and present it to the class next week.”

Obviously, the Church no longer considers collecting interest sinful. In fact, the Vatican itself runs a bank! The fact that Catholics lend and borrow money at interest can be traced to a gradual softening of the Church’s view until it came to consider only excessive interest as usury. This was finally codified in the 1917 publication of Canon Law. So, Pope Benedict’s strict construction was just wrong, according to current ecclesiastical thinking. How could a pope err on an issue of scripture and morality? The Catholic Encyclopedia explains it this way: “(‘Vix Pervenit’) was promulgated after thorough examination, but addressed only to the bishops of Italy, and therefore not an infallible Decree. On 29 July, 1836, the Holy Office incidentally declared that this Encyclical applied to the whole Church; but such a declaration could not give to a document an infallible character which it did not otherwise possess.”[11]Why would it make any difference to whom Pope Benedict was addressing his papal bull? Did the pope mean that interest was sinful in Italy but allowed in the rest of Christianity? I don’t recommend asking S’ter these question. She will probably just make you write a composition.

Pope Benedict was equally forthright in banning the Chinese Rites and deviant liturgical styles in India. He prohibited them entirely and overruled the eight concessions negotiated by Mezzabarba. The Catholic Church was then banned from China by the emperor, and many missionaries were executed. The pope protested vehemently, but he could do little from the other side of the globe.Pope Benedict enjoyed art as much as his predecessors. More unusual was the fact that he also appreciated science. Since Pope Sylvester II, the turn-of-the-millennium wizard, most popes had considered science rather inimical to faith. Pope Benedict boldly instituted scientific courses of study in the Church’s universities. He even removed the prohibition against heliocentric works.

In foreign policy Pope Benedict mainly strove to avoid conflict. He negotiated agreements with many sovereigns, and to some he ceded control over benefices and appointments in their realms. He supported the Stuart pretenders in Rome. An attempt – financed mainly by the French – by Bonnie Prince Charlie to invade England from the north was eventually thwarted by the English. The pope made a cardinal out of Prince Charles’s brother, Henry Benedict Thomas Edward Maria Clement Francis Xavier, the putative Duke of York, in 1747, when H. B. T. E. M. C. F. X. was only twenty-two. York remained a proud member of the original red hat club for six decades.The Catholic Encyclopedia describes Pope Benedict as “Great as a man, a scholar, an administrator, and a priest.”[12] It is hard to find much untoward written about him either by the papacy’s defenders or its detractors. Even an avowed atheist like Voltaire praised him. Nevertheless, Benedict has never been seriously considered for beatification. How can that be? Well, a few foibles probably tarnished his reputation’s luster:

- Maybe he was a little too accommodating to royalty. He acceded to the kings’ demand for an inquiry into the affairs of the Society of Jesus.

- He left behind a paper trail. Nobody would defend every word written by Pope Benedict XIV. Then, as now, those who survive close critical scrutiny have generally been careful to keep controversial opinions off of the printed page.

- His bull “A Quo Primum,” written for Christians in Poland, is especially troublesome. He wrote:

The Jews are cruel taskmasters, not only working the farmers harshly and forcing them to carry excessive loads, but also whipping them for punishment. So it has come about that those poor farmers are the subjects of the Jews, submissive to their will and power. Furthermore, although the power to punish lies with the Christian official, he must comply with the commands of the Jews and inflict the punishments they desire. If he doesn't, he would lose his post. Therefore the tyrannical orders of the Jews have to be carried out. ... you must see to it that neither your property nor your privileges are hired to Jews; furthermore you do no business with them and you neither lend them money nor borrow from them. Thus, you will be free from and unaffected by all dealings with them...

- Spinning the pasteboards was a favored pastime. Pope Benedict liked nothing better than a game of cards after a hard day composing scholarly treatises.

- The Holy Father had a real mouth on him. He repressed but never eliminated his lifelong habit of swearing like an infantryman with ingrown toenails on a forced march. He ordered crucifixes placed in every room that he frequented in order to remind himself to be vigilant about his language. Nevertheless, a torrent of blue verbiage occasionally erupted from the pontifical pie hole.

Three trends that previously had scarcely merited mentioning reached critical mass in the mid-eighteenth century.

1.Freethinking gained traction in Europe. Since the invention of the printing press, Europeans had grown better educated. As they became exposed to diverse ideas, many became less willing to submit to their king, their bishop, or, for that matter, their pope.

2.Colonial exploitation had at first largely been concerned with crushing the natives and transporting home their precious metals. By the 1700’s Europeans concerned themselves with extracting wealth from other colonial enterprises, especially agriculture. This process required land, which abounded, and cheap labor. Of course free labor, a.k.a. slavery, was even better.

3.The Jesuits.

The Black Pope’s Pope

The Society of Jesus attained remarkable influence around the globe. The Jesuits were the Church’s learners and teachers. By 1750 there were 273 Jesuit missions overseas. Some popes fretted that the order had become too influential, but for the most part its work was considered essential to the expansion of the Church’s influence. The Society always fiercely supported the papacy. Jesuits often provided valuable counterweights to the sophisticated intellectual argumentation of the Protestants. Sometimes, however, their concern for the native peoples of the colonial world put them at loggerheads with the priorities of European officials. Many complaints from France, Spain, and Portugal had reached Pope Benedict. He finally agreed to an investigation of the order’s activities. His death in 1758 preceded its completion. Lorenzo Ricci, the society’s newly elected Superior General (sometimes called the Black Pope), understood perfectly well how much the Society needed the pope’s whole-hearted support. Unfortunately, in the 1758 conclave the inexperienced Ricci prematurely exposed his hand. A veto by King Louis XV of France squashed the nomination of the Jesuits’ candidate, Cardinal Cavalchini.Ricci thereafter held his cards much closer to the vest(ments). His second choice was the Venetian Cardinal Carlo della Torre Rezzonico, who had received a Jesuit education in Bologna. Ricci spread some cash around and circulated a few promises on Rezzonico’s behalf, but he very carefully camouflaged his motives until he was absolutely certain of his vote count. He then rushed through Rezzonico’s election before the opposition could react. Rezzonico selected the name Clement XIII. He quickly terminated the investigation of the Jesuits.

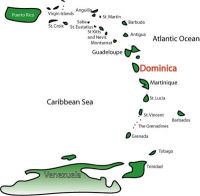

The Society’s man was on the throne in Rome, but problems emerged very rapidly, and with few weapons at his disposal Pope Clement was unable to stop the onslaught. The Portuguese government began arresting Jesuits in South America for treason. The Society attempted to persuade Catholics in Portugal to rebel against Sebastião Carvalho, the Marquis de Pombal, who acted as King José I’s prime minister. Pombal, who considered the Jesuit education system as a constraint on Portugal’s progress and the Jesuits’ separatist approach to Indian relations as detrimental to his plans for Brazil, used Indian rebellions in Uruguay and an attempt on the king’s life as grounds for declaring war on the Society. In 1759 he expelled from Portugal all Jesuits not already incarcerated and confiscated their possessions. Pope Clement provided for the outcasts in Italy, but doing so severely strained his budget. Antoine Lavalette, the Jesuit Superior-General of the French possessions in Central and South America, made the calamitous gaffe of mixing business with missionary work. His enterprises in Martinique and Dominica left him hopelessly in debt when a shipload of goods was seized by the English. Parliamentarians and freethinkers took the matter to court. The Jesuits were found responsible for Lavalette’s massive debt and a lot more – enough to bankrupt the entire society in France. Despite the pope’s pleas, in 1762 Parliament suppressed the society in France, and in 1764 the king extended the suppression to the French colonies. On the night of April 2-3, 1767, SWAT teams surrounded all Jesuit houses in Spain. The priests and brothers were rounded up and placed on ships bound for Italy. However, the pope could afford no more black-robed castaways, and he refused to allow them to land in the Papal States! The ships wandered around the Mediterranean searching for someone to accept their cargo. In the end they dumped six thousand or so Jesuits in Corsica, the home of the two-year-old Napoleon Bonaparte.Shortly thereafter the Jesuits were also banished from Sicily, the Kingdom of Naples, and the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza.

Pope Clement resorted to force. He deployed papal troops in Parma, the weakest principality that had expelled the Jesuits. The military impotence of the Papal States was quickly exposed. The Bourbons responded to the pope’s aggression by seizing the papal territories of Avignon, Benevento, and Pontecorvo. Pope Clement asked Empress Maria Theresa of Austria for help, but she declined to get involved; the trick of cajoling foreign powers into fighting the papacy’s wars had not worked for decades. In the end the pope sued for peace lest he lose his remaining holdings.In January of 1769 the Bourbons demanded a total suppression of the Jesuits. Pope Clement called for a consistory on the subject, but on the night before the meeting he expired suddenly. The Catholic Encyclopedia described the cause: “It was this that killed him. He expired under the shock on the night of 2-3 February.”[13] Clement XIII had expressly been chosen to champion the Jesuits’ cause. He did his best, but since the Thirty Years War the popes’ most reliable tricks had turned into duds. Nothing that he tried on the Society’s behalf came close to working.

Pope Clement XIII’s pontificate was not completely devoid of accomplishments. He ordered the mass production of fig leaves and strategically deployed them to conceal the nasty parts of Church statuary.More than half the attendees of the conclave of 1769 were from possessions of the Bourbon or Hapsburg families. The probability of electing a pro-Jesuit pope was zero. The highlight of the conclave was the surprise visit by Emperor Joseph II and his brother, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. Although it was expressly against canon law, the cardinals allowed the two royal Hapsburgs an insider’s view of the conclave. [14] The pair left after a day or so without incident.

The Death of the Society of Jesus

The Catholic Encyclopedia makes this stunning statement about the conclave of 1769: “Rarely, if ever, has a conclave been the victim of such overweening interference, base intrigues, and unwarranted pressure.”[15] Despite the clear majority held by the anti-Jesuit factions, 185 ballots were held before the cardinals elected Giovanni Ganganelli, a 64-year old Franciscan monk, the only member of any monastic order in the College of Cardinals. He had spoken in favor of the beatification of the Bishop of Palafox, a Spaniard who had opposed the Jesuits. Ganganelli took the name of Clement XIV, a pretty clear indication that he would strive to continue his predecessor’s resistance to the society’s annihilation. He did, for a while. Pope Clement appointed a tribunal to weigh the evidence against the Jesuits. For centuries popes had used this trick to avoid dealing with thorny issues. Unfortunately, Clement’s robust health allowed him to outlive the tribunal. The pope used the four years in which it cogitated about the Jesuits to address these matters:The tribunal finally ran out of excuses for delaying a decision, and it ruled against the Jesuits. Pope Clement vowed to suppress the order unless General Ricci accepted radical changes to its statutes. Ricci refused. The pope’s bull, “Dominus ac Redemptor,” suppressed the order.[16] Fr. Ricci was confined in Castel Sant’Angelo. A few weeks after the notice was served to the Jesuits, Pope Clement, who appeared to be in good health, contracted an illness that resulted in his death after about a month of agony. And what a spectacular death it must have been:

Decomposition had actually preceded death, and in those days it was well nigh impossible to cope with such conditions. The Pontiff himself was obviously obsessed with the conviction that he had been poisoned, and it was the popular belief amongst his contemporaries.[17] The details of his laying-out are horrifying. His remains had to be encased in plaster, and Cardinal Marefoschi, who according to the ceremonial should have placed a cloth over the dead Pope's face, feigned illness so as to escape the ordeal, the major-domo who had to take his place being so overcome that he closed his eyes and threw the veil in the direction of the bed without approaching it. A layer of plaster was hastily spread over the aperture where those features once so pleasing to look upon should have been exposed; and so was obliterated all trace of the brave, wise and virtuous Pope who had borne the name of Clement XIV.[18]

Cassanova’s memoirs insisted that Pope Clement had been poisoned by the Jesuits. Conceding a lack of hard evidence, he argued that “moral certainty assumes the force of scientific certainty.”In the year of which I am speaking, the third of the Pontificate of Clement XIV, a woman of Viterbo was put in prison on the charge of making predictions. She obscurely prophesied the suppression of the Jesuits, without giving any indication of the time; but she said very clearly that the company would be destroyed by a pope who would only reign five years three months and three days—that is, as long as Sixtus V, not a day more and not a day less. Everybody treated the prediction with contempt, as the product of a brain-sick woman. She was shut up and quite forgotten. I ask my readers to give a dispassionate judgment, and to say whether they have any doubt as to the poisoning of Ganganelli when they hear that his death verified the prophecy.[19]

* * *

“S’ter, I don’t get it. My uncle is a Jesuit. The school he teaches at has gobs of ‘em. If the pope s’pressed ‘em, where’d they come from?”

“‘The school at which he teaches’, not ‘The school he teaches at.’ Strive never to end a sentence or a clause with a preposition.”

[1] Charles’s father married his own niece. The couple was related in other ways, too; in all Charles was descended from Joanna the Mad twice as great-great-great grandson and through twelve other paths! Contemporaries attributed his problems not to heredity but to a bewitching by unnamed parties. Thank goodness they were unnamed; the Spanish Inquisition was still going strong. Charles himself presided over the most dramatic auto-da-fé ever. Since the witch responsible for his condition was never located, Charles was exorcised as a child, but the ceremony did not seem to help.

[2] Pirie, op. cit., p. 228.

[3] As the crises mounted, Clement VII, Pope Btfsplk I, started growing a beard, as did the next twenty-three popes. Clement XI, Pope Btfsplk II, broke the string by shaving. Incredibly, this link was missed by Pastor, Von Ranke, and every other papal historian except for me.

[4] Griesinger insisted that he was poisoned by the Jesuits. Theodor Griesinger, The Jesuits: A Complete History of Their Open and Secret Proceedings from the Foundation of the Order to the Present Time, Translated by A. J. Scott, M. D., W. H. Allen, 1885, p. 451.

[5] Maybe not so catastrophic. De Rosa argues that “Pope Clement XI arguably saved the world from catastrophe” because instead of the billion Chinese atheistic family planners in the twentieth century, there might have been two or three billion Chinese Catholics. Op. cit., p. 235.

[6] Pedro de Luna, Benedict XIII of the Avignon obedience, claimed the papacy during the entire period of 1394-1423.

[7] The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. IV, p. 31.

[8] “We decree that no Cardinal may be expelled from the said elections on the grounds of any excommunication, suspension, or interdict whatever.” Pope Clement V’s bull quoted in The North British Review, December 1866, p. 161.

[9] The golden rose was a treasured gift from the pope to favorite Catholic rulers. King Henry VIII of England, who later suppressed the monasteries, confiscated much monastic property, and started his own Church, received one from three different popes. It is now usually given to charitable or religious institutions.

[10] The Catholic Encyclopedia, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 434.

[11] Ibid., Vol. XV, p. 236. Sister Mary Immaculata would be ashamed that The Catholic Encyclopedia committed two grammatical errors in the last sentence. It used a semicolon rather than a comma before “but” and employed “which” instead of “that.”

[12] Op. cit., Vol. II, p. 435.

[13] Op.cit. Vol. IV, p. 34.

[14] Valérie Pirie (op. cit., p. 268) and others claimed that the imperial brothers were allowed into the conclave itself. They certainly were in Rome at the time.

[15] The Catholic Encyclopedia, op. cit., Vol. IV, p. 34.

[16] It was not completely suppressed. At the requests of their sovereigns Jesuits continued to teach in Prussia and to act unhindered in Russia. Elsewhere Jesuits were expected to join other orders. Most did what was required, but they maintained a communication network among themselves throughout Italy.

[17] Cormenin asserted that the Jesuits poisoned a fig with Aquetta di Napoli, a form of Spanish fly. Op. cit., Vol. II, pp. 397-398.

[18] Valérie Pirie, op. cit., pp. 274-275.

[19] The Memoirs of Jacques Casanova de Seingalt, translated by Arthur Machen, Putnam, 1959, p. 399.

| |

| |

Bankable Bar Bets

$ Charles II, the last Hapsburg king of Spain, ruled the most powerful nation on earth for over a decade despite the fact that he was severely retarded and could barely walk and talk. The young king’s mother was also his first cousin. He was descended from Joanna the Mad fourteen different ways.

$ King Charles II of Spain was exorcised as a child.

$ Pope Clement XI delayed three days before accepting his election as pope.

$ James III, the Stuart pretender to the English throne, lived in Rome for decades. He was heavily subsidized by the pope and the king of France.

$ Shortly before Christians were banned from the country, the Jesuits held several high-ranking positions in the Chinese court. One supervised the pouring of 132 cannons.

$ Pietro Francesco Orsini mistakenly selected the name Benedict XIV. Evidently he forgot that the first Benedict XIII was considered a schismatic antipope.

$ Pope Benedict XIII was blind and spent most of his decade-long pontificate in bed.

$ Pope Benedict XIII banned wigs.

$ Pope Benedict XIII’s right-hand man, Cardinal Coscia of Benevento, and his cronies robbed the Church blind.

$ Pope Clement XIII named an eight-year old cardinal.

$ Three different pontiffs awarded the Golden Rose, the most prestigious award that a pope can give a sovereign, to King Henry VIII, who later founded the Church of England.

$ Pope Benedict XIV issued an official papal bull outlawing the charging of interest on loans.

$ Bonnie Prince Charlie’s brother had seven middle names. Even though he was the Duke of York, he was named a cardinal at age twenty-two and remained one for sixty years.

$ Pope Benedict XIV was widely known for his cursing and card-playing.

$ King Charles III expelled the Jesuits from Spain and its colonies, but Pope Clement XIII would not accept them in Italy. The ship carrying the priests sailed around the Mediterranean for six months before dumping them in Corsica two years before the birth of Napoleon Bonaparte there.

$ Pope Clement XIV was elected on the 185th ballot.

$ Pope Clement XIV’s pontificate lasted exactly as long as Pope Sixtus V’s. This was reportedly predicted by a nun, who also foretold that Pope Clement would suppress the Jesuits, which he did.

$ The Vatican tolerated castration of choirboys until the twentieth century.