Chapter 20: “Viva la Regina!”

No reasonable person expected that the outlandish behavior of the Renaissance and Reformation popes could be matched by the Bishops of Rome of subsequent decades. The bar was too high. Nevertheless, the next two centuries produced a few eye-catching performances, and they will be duly noted.

The Thirty Years War and its aftermath blunted the papacy’s edge. The institution’s neutrality during most of the war undercut its influence in the peace negotiations. Thereafter the popes wielded little political power. On the other hand, Spain – loyally Catholic to its marrow – dominated the rest of Italy. The Church’s holdings in the Papal States were safe. Spain was so rich and powerful that she appeared likely to lord over Italy for the foreseeable future. Who could challenge her? As long as Spain held the territories bordering the Papal States, the popes’ political and military tricks gathered dust. Few crises necessitated defensive sleights, and aggressive pontifical maneuvers, no matter how ingenious, were futile. At the same time Protestant Europe was largely beyond the pope’s hegemony. He could not remove Protestant leaders, and as long as they remained in power, inhabitants of Protestant states were beyond his reach. Even if the Inquisition found one of them guilty of heresy, who would execute the sentence?The papacy needed someone to shake things up a little. Perhaps the least likely person imaginable for that task would be royalty, a Protestant, and a woman.

The Queen of Nowhere

Gustavus Adolphus, the Swedish king and renowned hero of the Thirty Years War, was slain in battle. His only child, Christina, born in 1626, had quite an unusual upbringing. Her autobiography claimed that she was born with a caul covering her entire torso. She was large and hairy, and she emitted such coarse sounds that at first the midwives were delighted at the birth of the male heir that her father, like all European sovereigns, desperately desired. Christina’s gender disappointed him so much that he ordered her raised as a male. She dressed like a boy, played boys’ games, and received a young man’s education. No Barbie dolls were to be found in the royal toy chest; her favorite pastime was hunting those godless killing machines commonly known as bears. Her father died when she was only six. Her mother, who never had much use for Christina, allegedly contributed to her education by introducing her to alcohol and recommending that she sample as many different varieties as possible. Fortunately the queen mother exerted little influence[1] on Christina, who was raised by elderly statesmen and intellectuals. She came of age in 1644 and ruled in her own right as Sweden negotiated the terms of peace. Her country fared quite well in the settlement. In 1650 Christina was crowned queen of Sweden, but she never captured the hearts of the Swedish populace. Here are a few reasons:• Swedes were baffled by her attitude toward marriage. In an era in which rulers moved mountains to assure that they had heirs, she insisted in a public speech that she was not able to wed.[2] She never explained why.

• She seemed excessively intellectual. She loved French culture, and trendy philosophical schools intrigued her. She even invited René Descartes to the Swedish court. He arrived in Stockholm in 1650 shortly before his death.• Christina’s fascination with the Catholic faith repulsed the solidly Lutheran Swedes. Evidently Catholicism’s emphasis on sexual purity intrigued her. She wrote a letter of inquiry to the General of the Jesuit order, Francesco Piccolomini. In 1652 he dispatched Paolo Casati and Francesco Malines to explain the faith.

In 1654 Queen Christina abdicated in favor of her cousin. She astutely arranged a comfortable pension for herself and her retainers and drew up an official document that insisted that she remained a sovereign. She delivered a tearful speech and then left Sweden disguised as a man named Count Dohna. She checked Europe on Fifty Kronor a Day out of the Stockholm Public Library and backpacked across the continent for eighteen months. Sometimes as the count, sometimes revealing her regal identity, she made stops in Hamburg, Antwerp, Brussels (where she was privately baptized by a Catholic priest), Innsbruck, and several Italian towns.

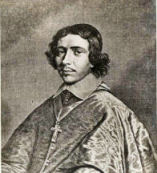

The queen knew how to make an entrance. Riding a white horse and dressed as an Amazon she appeared in Rome in December of 1655. The newly elected Pope Alexander VII recognized what a public relations coup was at his doorstep. He set Her Highness up in the Palazzo Farnese, one of the most elegant buildings[3] in Rome. Bear hunting was prohibited in the Eternal City, but she could fish in the Tiber from her backyard whenever she was so inclined. The pope personally administered the sacrament of confirmation to her. She diplomatically chose Alexandra as her confirmation name. Christina’s comportment was not exemplary. She might have profited from greater exposure to some Ursuline-administered discipline in her youth. Evidently someone had assured her that lofty personages such as herself were not expected to follow the letter of canon law. It was probably just as well; she had little use for regulations. Her unusual dress and behavior continually generated speculation and gossip, much of which was probably instigated by Spaniards who resented her influence. Shortly after the queen’s arrival in Rome, Pope Alexander selected a young cardinal named Decio Azzolino (also spelled Azzolini) to act as liaison between His Holiness and Her Highness. The bond between the queen and the cardinal endured for decades. He was poor[4], intellectual, and idealistic; she was rich, intellectual, and totally unpredictable. He was the pope’s cryptographer; codes fascinated her, too. He took a vow of celibacy; she never took a vow, but the result was the same. In all ways they were a great match. For several decades they exchanged written correspondence, mostly in code. A glance at her decoded letters verifies that she was deeply in love with him. Some have speculated that he did not return the affection, but why else he would communicate as often as he did? When both were in Rome he wrote to her as soon as he rose every morning and right before bedding for the night. He usually sent her several additional missives throughout the day.Travels With Christina

In 1656 Queen Christina visited France. She had always craved intellectual stimulation, and the City of Light, where she had already established an academy, was the best place to meet and greet the elite of the nascent thinking class. According to the Duke of Guise she spoke perfect French and “knows more than all the Academy and Sorbonne put together.” She attempted to set up the teen-aged King Louis XIV with the niece of his regent, Cardinal Mazarin. Mazarin, however, frowned on the match and sent Christina packing.On her second trip to France she traveled incognito, often dressed as a man. Mazarin provided accommodations in the fabulous chateau at Fontainebleau. Her goal was to promote her latest scheme, fomenting an uprising in Naples (still part of the Spanish Empire) so that she could become its queen. Knowing that France and Spain had disputed about this territory for centuries, she conspired with Cardinal Mazarin in the hope that France could supply enough military support to offset Spain’s inevitable resistance.

Unfortunately, the keeper of the queen’s horses, Gian Rinaldo Monaldesco (also spelled Monaldeschi), a Neapolitan, evidently leaked her plans to Spanish officials. Christina ordered Monaldesco’s execution, and she was present when his throat was cut in Fontainebleau. A firm believer in the divine right of queens, she thought nothing of snuffing a disloyal subject. The terms of her abdication had deliberately been crafted to assure diplomatic immunity wherever she traveled. Whether the Jesuits ever mentioned the fifth[5] commandment during her indoctrination in the Catholic faith was not covered in Christina’s diary. Europeans were shocked that an unemployed monarch would murder a foreign-born servant in cold blood. Although no one officially charged her with any crime, civil or religious, the queen paid a high price in terms of public relations. She was forcefully requested to leave France. When she returned to Rome, the pope asked her to vacate the Palazzo Farnese as well. She obediently moved across the river to the Palazzo Riario.[6]At Fontainebleau Christina also set up a chemistry lab and conducted experiments. She didn’t discover Radium or a cure for the plague, but neither did she blow up the chateau.

Christina twice returned to Sweden. When Charles X, the cousin who succeeded her on the throne, died unexpectedly in 1560, she filed a claim for pension funds that she considered her due. Her second visit turned ugly when the Swedes discovered a Catholic priest in her retinue.In 1667 Christina applied to become Queen of Poland.[7] She envisioned herself as a new Joan of Arc leading the Polish army against the Turks. She allegedly asked a monk to spread a rumor of a prophecy about her becoming queen.[8] However, the royal selection committee never even called her in for an interview. Ignoring the clear instruction on careerbuilder.com to e-mail or fax a curriculum vitae with references, she overnighted the Polish authorities a ninety-minute DVD of her accomplishments and aspirations. Christina Would Love to Do Warsaw was perhaps too avant-garde for seventeenth-century Polish tastes.

Il Squadrone Volante

In the conclave of 1655, just before Christina’s horse trotted into Rome, a new faction began making its presence felt – young Italian cardinals who called themselves il Squadrone Volante (the Flying Squadron), or SV for short. Over their traditional crimson vestments and birettas, club members favored goggles, leather helmets and jackets, and long white silk scarves. Their raison d'être was to re-establish the papacy’s primacy by finding the most worthy candidate regardless of nationality or politics. Azzolino, whose red hat was only a year old, was a charter member. The French and Spanish cardinals held irreconcilable views. Donna Olympia Pamfili struggled to control the many cardinals appointed by her deceased brother-in-law, Pope Innocent X, a group that audaciously called itself “God’s Faction.” Their influence, however, was severely limited by the strain of osteoporosis that afflicted Donna Olympia in her later years. Her arms had shrunk so much that they could no longer reach her pockets at all, a condition exacerbated by the fact that those pockets were weighted down with precious metals. The SV promoted Cardinal Chigi’s candidacy. It schemed behind the scenes with Cardinal Retz, who, after being banished from France by King Louis XIV, had subsequently cultivated a strong relationship with the Spanish. Eventually Donna Olympia was pressured into withdrawing her opposition, and after eighty days Chigi was elected Pope Alexander VII. Christina soon became the SV’s patron. Her fame as an intellectual Protestant monarch who had seen the light still outweighed her notoriety as a wildly unpredictable cross-dresser. Her association with the SV, most of whom were relatively young men with little political clout, even lent them cachet in the upper echelons of Roman society.During Alexander’s eleven-year pontificate, the SV cardinals gained experience. In the conclave of 1667 they once again plotted secretly and formed alliances powerful enough to win the election of one of their own, Julius Rospigliosi. His pleasant nature had served as the basis of excellent relations with both France and Spain maintained over decades of diplomatic postings. Since Christina was in Germany applying for permission to return to Stockholm, she exerted no direct influence on the conclave. Its outcome, however, undoubtedly delighted her.

Although Rospigliosi was only sixty-seven when he became Pope Clement IX, he died after only two and a half years. During his pontificate the SV became quite influential in Rome, and Christina was in her glory. Clement’s intellect equaled hers, and he provided her a generous allowance.The last conclave in which the SV formed a cohesive voting bloc was in 1669-70. Christina supported Cardinal Vidoni. Azzolino himself managed the SV cardinals. Realizing the difficulty of getting their choice elected on an early ballot, he adroitly postponed the inevitable for four months in the hope that Vidoni might emerge as a compromise candidate. In the early scrutinies Azzolino pretended to denigrate Vidoni. Later he reversed course and advised Christina via coded messages to be candid about their plans because the cardinals all assumed that everyone else was lying.

Cardinal D’Elci received twenty-seven votes on the first ballot. Cardinal D’Este produced a veto of D’Elci’s candidacy signed by King Louis XIV, and D’Elci died shortly thereafter. Some contended that the shock of the news killed him. The action outside the conclave was equally interesting. Queen Christina waged an epic struggle with Marie Mancini, the niece of Cardinal Mazarin whom Christina had years earlier tried to pair up with the youthful Sun King. The object of the ladies’ attentions was the French faction’s leader, the Duc de Chaulnes. Christina emphasized Spain’s vehement disapproval of Vidoni in hopes of persuading de Chaulnes that his enemy’s enemy was his friend. Marie, who supported Cardinal Bonvisi, was less subtle; she simply seduced de Chaulnes.Four months passed; consensus seemed hopeless. This time the SV could not break the deadlock with its candidate. Instead, the French surprisingly suggested Cardinal Altieri as a compromise candidate. He was an octogenarian without a single nephew. The Spanish cardinals, worried about ill treatment from Vidoni because of their past behavior toward him, eventually endorsed the French suggestion. Even the SV, except for Azzolino himself, succumbed in the end.

One important cardinal objected even more strenuously than Azzolino – Altieri himself. The man whom Cardinal de’ Medici had allegedly called “the idiot” had to be dragged kicking and screaming – not a metaphor – into the chapel. However, after his whining went unheeded, he acquiesced and took the name Clement X.In Christina’s last conclave of 1676 she strongly supported Cardinal Conti, but his candidacy was hopeless. The influence of both Christina and the SV had waned during Clement’s six-year pontificate. Moreover, Cardinal Conti’s obsession with clocks made it difficult for anyone to take him seriously. The highlight of the tense conclave occurred when Cardinal Colonna grabbed Cardinal Maidalchini, Donna Olympia’s nephew, by the throat and attempted to strangle him. The cardinals eventually settled on Benedetto Odescalchi, a stern but fair-minded native of Como, who became Pope Innocent XI. The contrast in the personalities of the pope and the queen made for a fiery relationship.

Christina’s Popes

The early seventeenth century showered humiliation on both the Church and the papacy. For twenty-five years the popes virtually ignored the most important religious war since the crusades. The negotiators of the Peace of Westphalia paid little heed to the Church’s interests. Furthermore, Europeans knew that Innocent X, the pontiff during the last years of the war and the peace talks, was under the thumb of his avaricious sister-in-law. Nepotism and greed in Rome approached the scandalous levels of the Renaissance.

The cardinals who met in the first post-war conclave in 1655 exhibited little unity of purpose. Dissent was as widespread as ever. The Barberini brothers, France, Spain, the Medicis, and Donna Olympia manipulated the votes toward their own candidates. For weeks no faction came close to gaining the necessary majority. The young cardinals grew restless and started playing pranks. After eighty days and an untold number of deals, the cardinals settled on Fabio Chigi, the papal legate at the peace talks. He took the name Alexander VII to honor Alexander III, a fellow Sienese. Pope Alexander frequently proclaimed himself unworthy of the office. It was an accurate assessment. Even though his own father was Pope Paul V’s nephew, he promised to eliminate nepotism, and he kept his promise for one year and seventeen days; he even banished his relatives from Rome. Unfortunately, he neglected to fill critical positions in the curia, and the Church was essentially leaderless. In June of 1656 the pope invited his brother Mario to Rome and named Mario’s son Flavio the cardinal-nephew and protonotary apostolic. The remaining thirty-seven cardinals that he appointed were not named Chigi, but Alexander turned over the management of most of the Church’s affairs to his relatives. The modestly successful banking family took advantage of the situation to become one of the richest and most influential houses in Italy. The first SV pope showed surprisingly little interest in Church affairs. He funded universities, construction, and art, including Bernini’s commission for the redoubtable double colonnade surrounding St. Peter’s square. The same artist fashioned an elaborate tomb for him in St. Peter’s Basilica. The pontiff also bankrolled many projects in Siena and provided generous patronage for Queen Christina’s undertakings.Alexander was a dreadful cosmologist. He placed heliocentric works on the Index, and his bull “Speculatores Domus Israel” clearly declared that all works affirming the earth’s motion were heretical. Anyone denying that the earth was perfectly stationary risked the Inquisition.

In 1667 Julius Rospigliosi assumed the throne as Pope Clement IX. Rospigliosi was an accomplished musician and one of the era’s preeminent dramatists. In fact, he may be better known for writing the very first comic opera[9] or, if you prefer, the first musical comedy, than for his accomplishments as pope. He also opened Rome’s first public opera house. The locals acclaimed Pope Clement for ending the grain monopoly in Rome. He had no aptitude for one traditional papal role; he did little or nothing to advance his family’s fortunes. One does not find “Rospigliosi” or “Clement IX” engraved on buildings and chapels throughout central Italy with the same ubiquity as many other papal names. Pope Clement connected personally with the people of his diocese; he even kept regular hours in the confessional.Pope Clement’s foreign policy focused on preserving even-handed relationships with both France and Spain. He also vigorously supported Venice’s effort to keep Crete out of the hands of the Turks. The news of the failure of that struggle in 1669 may have been more than his weak heart could bear.

Eighty-year Emilio Altieri became Pope Clement X in 1670. Even if he was the simpleton that some of his colleagues considered him, he performed the most ingenious papal trick of the seventeenth century. He never desired the papacy, and he obviously lacked the physical and mental vigor to perform its duties competently. This would not have raised a serious problem for many popes; when they tired of managing the Church, they farmed out important responsibilities to their nephews or other relatives. Pope Clement, however, lacked nephews, and he could not countenance remanding his pontifical duties to a stranger. What to do? He proposed to the Paluzzi family that one of its young men should marry his niece, Laura Caterina Altieri. If the entire Paluzzi family agreed to assume the name Altieri, the pontiff would adopt them en masse and designate one as his cardinal-nephew! The Paluzzis gladly agreed. Why not? They were immediately elevated to the top echelons of Roman society. Paluzzi, Altieri, what’s in a name? The pope himself performed Laura’s wedding ceremony, and then the Paluzzi boys assumed management of the Church. Pope Clement’s public appearances always included his adopted family, which made nearly all important decisions. They raised taxes and in 1675 declared an extra Jubilee in order to generate more tourist revenue. When the pope died, the neo-Altieris refused to invest their new-found wealth in an enterprise with such a limited up side as a papal funeral. Having lacked the foresight to specify decent funeral arrangements in the adoption deal, Pope Clement was sent away as a pauper.The Principled Pontiff

The last pope in Christina’s Rome was Innocent XI, who ruled from 1676 to 1689. He was born in Como, which is almost in Switzerland, and spent most of his Wonder Years in Geneva. He was the straightest arrow to sit on Peter’s Throne in several centuries, and it is insulting to lump him with Christina’s other popes. He absolutely refused to engage in nepotism. Not even a little! He greatly respected and loved one of his nephews, but Innocent was a man of principle. Only relentless nagging from the cardinals stayed him from publishing a bull eliminating nepotism forever. Pope Innocent slashed his own budget and exhorted the cardinals to do the same. He issued several decrees regulating the comportment of private citizens in Rome. He forbade women from wearing masks in public and even enacted strict laws limiting the cut of their outfits. He closed down the gambling houses in Rome. In 1676 he even shuttered all Roman theaters. He transformed the opera house into a granary. The opera house! Bread is certainly important, but Rome is in Italy, not Switzerland. Would life for Italians really be worth living without opera? These restrictive measures made the pope’s popularity in Rome equivalent to General Sherman’s in Atlanta. He was unfazed; the papacy to him was no popularity contest. Innocent XI declared that even in marriage practicing sex strictly for pleasure was sinful. Actually, his papal bull denied that the practice was permissible, but popes often preferred negative language for their judgments.Innocent criticized the use of torture by the Inquisition. Not exactly a humanitarian, at least he had a better feel than his predecessors for what worked and what was counterproductive.

Practically no one living or dead measured up to his standards. In his thirteen-year pontificate he found not one Christian holy enough for canonization. He even struggled to find any worthy prelates. Not only did he refuse to flood the college of cardinals with his cronies; at his death ten vacancies remained for his successor to fill. This was totally unprecedented.

Pope Innocent frequently quarreled with King Louis XIV about the appointment of the clerical hierarchy in France. This dispute was fundamentally the same conflict over “investiture” that had simmered for centuries. King Louis held the strongest political cards, but the pope characteristically refused to fold. Because ambassadors and legates with diplomatic immunity in Rome were so numerous, great portions of the city had become havens for criminals. In 1687 the pope eliminated the practice of diplomatic sanctuary. Louis was incensed, and the French mounted a showy pseudo-invasion of the Eternal City, perhaps in a ploy to provoke the pope into a futile military response. The Holy Father, however, avoided confrontation. Instead, he responded with excommunications and an interdict limited to the church frequented by French troops in Rome. Convinced that God was on his side, he eventually persuaded other European rulers to pressure King Louis into toeing the line. Pope Innocent also lobbied Christian rulers to take the threat of the Turks seriously. He persuaded Jan III Sobieski, King of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth[10] to help break the siege of Vienna in 1683. In 1686 Buda, which the Turks had held for 145 years, was liberated by the armies of the Hapsburg empire.Pope Innocent had at least one memorable confrontation with Queen Christina. When the pontiff eliminated diplomatic sanctuary, nearly everyone except the French went along with the idea, at least in theory. That included Queen Christina, but she was nonplussed when papal policemen actually entered her property, which she considered to be her realm.

A man convicted of some offense, was seized by the sbirri:[11] as they were driving him with blows through the streets, he escaped, and ran to take shelter in a stable attached to the palace of the queen. It was locked, but he seized upon the staple, or chain, of the door with such force, that no efforts of the sbirri could tear him away: they put a cord round his neck, and still, with the courage or the obstinacy of despair, he kept his hold, though on the brink of strangulation. Christina was at this moment in her chapel, and a multitude had gathered round her palace: the noise of the affray, the shouts, cries, and imprecations of the populace, reached her. She no sooner learned the cause, than she ordered Landini, the captain of her guards, and another of her attendants, to rescue the man, and to cut down the officers of justice if they resisted: the cowardly sbirri fell on their knees, and at once resigned their prisoner, who was carried off, amid shouts of “Viva la Regina!” and placed in safety.[12]

The pope’s treasurer demanded that Landini and his companion be surrendered to papal guards for trial. Christina was incensed that the sbirri had violated the boundaries of the mini-kingdom of her palatial grounds. She responded thus in writing to the treasurer: “To dishonor yourself and your master is then termed justice in your tribunal? I pity and despise you, now: but shall pity you much more when you become cardinal. Take my word that those whom you have condemned to death, shall live, if it please God, some time longer; and if they should die by any other hand than His, they shall not fall alone.” She then fortified her lodgings and armed herself and her attendants. When she went out, she always brought armed guards. Pope Innocent, however, refused the bait. He discounted her behavior as the flightiness to be expected of a woman. Christina, who was renowned for belittling women, considered this the ultimate insult. Nevertheless, she maintained her aplomb. When the pope terminated her papal pension, she thanked him in writing “for having removed from me such a subject of shame and humiliation.”Pope Innocent died in 1689, not long after Christina’s passing. The pope’s nephew Don Livio, despite the fact that he received neither benefices nor appointments from his uncle, provided a splendid funeral. The papal treasury was bountiful, but Don Livio tapped his own funds.

A 242-year investigation culminated with the beatification of Innocent XI by Pope Pius XII in 1956. However, he was never canonized. In one respect Innocent XI was not the last of Christina’s popes. The queen took young Giovanni Francesco Albani under her wing and enrolled him in her exclusive Academy. At the turn of the century he reigned as pope[13] for two decades.

Christina’s Death

In 1689 Christina considered leaving Rome. However, before she could begin actualizing a new fantasy in which she ruled a German principality, she took ill with a malignant fever. Twice she seemed near death, and twice she recovered before falling ill again. Near the end she sent Albani to ask pardon from Pope Innocent XI, and without hesitation the pontiff granted her plenary absolution for her sins.Cardinal Azzolino was in close contact with the queen right through her death at the age of sixty-three on April 19, 1689. Her will, which the cardinal himself may have drawn up, left nearly everything to him. It is petty to find fault here; he lived less than three months after her demise, and he devoted his little remaining time to aggrandizing Christina’s memory. He arranged for her to be buried in the Basilica of St. Peter, an honor granted to only four other women.[14] Pope Innocent XI himself officiated at her funeral mass. Located near Michelangelo’s Pietà in the same great church stands an impressive monument to the Queen of Nowhere.

[1] Von Ranke recorded that Christina in fact drank nothing but water.

[2] Speculation has persisted that Christina might have been an hermaphrodite. An autopsy in 1965 was inconclusive.

[3] Michelangelo himself had redone part of the façade. It now houses the French embassy.

[4] By this time the legendary wealth of the cardinals had diminished somewhat. Cardinals like Azzolino were chosen for their performance at universities. Lacking inheritances and benefices, they depended on stipends from the pope. While not indigent, they bore little resemblance to the cardinals of the previous two centuries.

[5] “Thou shalt not kill” is fifth by the Catholics’ count; most heathens refer to it as #6.

[6] The palazzo, which is in Trastevere, was expanded in the eighteenth century. It is now known as Palazzo Corsini, which houses the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica.

[7] This is not the most bizarre pretension in history; Christina’s family had a claim to the Polish throne. The same could not be said for Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, who declared himself King of Scotland and even wore a kilt at a 1975 funeral in Saudi Arabia. Newspaper coverage did not indicate whether he wore the traditional undergarments.

[8] Johann Joseph Ignaz von Döllinger, Dr. J. J. I. Von Döllinger's Fables Respecting the Popes in the Middle Ages, Dodd & Mead, 1872, p. 277.

[9] “Chi soffre speri,” premiered at the Palazzo Barberini in Rome on February 27, 1639.

[10] It is therefore probably a good thing that Christina did not get the job of Queen of Poland after all.

[11] Sbirri were papal police. The term is now pejorative; think Scarpia.

[12] Anna Jameson, Memoirs of Celebrated Female Sovereigns, H. Colburn and R. Bentley, 1831, pp. 99-100. The creative punctuation belongs to Ms. Jameson and/or her editors.

[13] Pope Clement XI’s story is in Chapter 21.

[14] The others are, according to “Notes and Queries” from Oxford University Press, the Countess Matilda of Tuscany, Queen Charlotte of Cyprus, Agnese Gaetani Colonna, and Maria Clementina Sobieska.

| |

| |

Bankable Bar Bets

$ The attendants at her birth mistook Queen Christina of Sweden for a boy.

$ Christina’s favorite pastime as a young lady was hunting bears.

$ Christina reigned for a decade as Queen of Sweden. Later she applied for the same job in Poland.

$ Idi Amin declared himself King of Scotland.

$ Pope Alexander VII banned all publications that denied that the earth was stationary.

$ Pope Clement IX was better known as a dramatist than as a clergyman. He wrote the libretto for the first comic opera.

$ Pope Clement X, at the time an eighty-year old cardinal, had to be dragged kicking and screaming into the Sistine Chapel to acknowledge his election.

$ Pope Clement X adopted the entire Paluzzi family when one of them agreed to marry his niece. Thereafter the Paluzzis ran the Church.

$ Pope Innocent XI closed all theaters in Rome. He also published regulations on the cut of the garments worn by Roman women.

$ Pope Innocent XI claimed that engaging in marital sex solely for pleasure was sinful.

$ At Pope Innocent XI’s death the positions of ten cardinals were left unfilled.

$ Queen Christina is one of five women entombed in St. Peter’s Basilica.