Obsession about papal history. Continue reading

On Saturday, January 25, 2003, a momentous event occurred in my life. I was, as usual, working in my office at TSI in East Windsor. My Bose radio was tuned to the local NPR station. I don’t remember what I was working on, but I do remember Scott Simon’s interview of A. J. Jacobs on Weekend Edition about his quest to become the smartest person in the world by reading the Encyclopedia Britannica from beginning to end. On that show he reported that he had just finished reading the letter H. To my surprise and delight the entire interview has been posted here.

Most of the conversation concerned the account that he read in the F volume concerning the corpse of the ninth-century Pope Formosus, which was disinterred and put on trial in January of 897 by a subsequent pope named Stephen1. Jacobs described the occasion as it was depicted in 1870 in a famous painting by Jean-Paul Laurens called The Cadaver Synod. Having been found guilty, Pope F was excommunicated and defrocked. The thumb and forefinger that he used for consecrating the host were broken off. His skeleton was dumped in the Tiber. All of Pope F’s decrees and investitures were declared invalid.

That is all that Jacobs mentioned, but it was not, as I soon discovered, the end of the affair. The rest of the shocking story has been related in Chapter 5 of my book Stupid Pope Tricks, which can be read here.This radio show had a startling impact upon my life. Although I had attended Catholic schools for twelve years, I suddenly realized that I knew embarrassingly little about Church history. I could name all of the popes of my lifetime, and I knew that the first one was St. Peter himself. In between was a large blank slate. I had never heard of Formosus or Stephen, and I wondered if perhaps A. J. Jacobs had not gotten the story quite right.

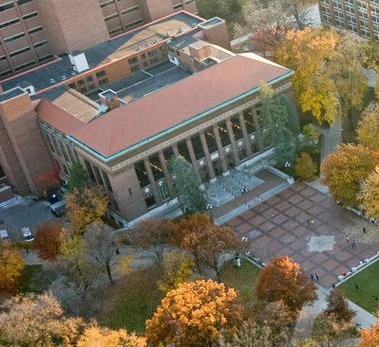

So, I got no more work done that day or the next. I was too busy googling and reading. I soon discovered that an enormous number of entire books had been scanned by Google in a project that defied belief. At the time the company had nearly finished scanning all the books at the University of Michigan’s enormous library2. The ones that were in the public domain were available online in toto and free. Almost every work in which I was interested was available at my fingertips. If I googled “Formosus”, every reference in every one of these books showed up, and, best of all, there were no ads cluttering up the search because no one had named a product or company after the poor fellow.

I started with Pope Formosus and worked backwards and forwards. I eventually realized that all written records of that period were quite suspect, but what Jacobs reported seemed to be pretty accurate, at least as far as anyone knew. One of the first additional things that I discovered was that shortly after the notorious incident Pope Stephen VI was strangled by a mob of the supporters of Pope F. Jacobs did not mention that both of the principals in the story were pontiffs in the first century of the era that lasted for more than a thousand years in which the pope was the ruler of a strip of land in central Italy that stretched from coast to coast. Their conflict was more political than theological.

The catechism that we used in parochial school promulgated the idea that the papacy had been an unbroken chain of successors to St. Peter. That notion did not survive the weekend in my new level of understanding. Duplications—when two or more men claimed to be pope at the same time—and gaps of several years when no one was recognized as pope were evident. The pope is, by definition, the Bishop of Rome, but for seventy years in the fourteenth century no pope ever set foot in Rome. They lived in Avignon in France and were absentee landlords for tens of thousands of Italians. I was also astonished to learn than during the first millennium of the papacy there wasn’t even agreement upon how the successor to a dead pope should be chosen. Some were appointed by kings or emperors.

I had previously assumed that most popes had been saints. The official Church position has always been that the Holy Spirit has inerrantly guided the cardinals (or whoever) who elected or appointed them. The popes at the top of the chronological list (about whom almost nothing is known beyond names and dates because all records were destroyed at the beginning of the fourth century) were considered saints, but at the time that I began my research only three popes3 had been canonized in the last one thousand years! One pope, John XII, was apparently not even a teenager yet when he became Supreme Pontiff, and once he became pope he was, according to all accounts, pretty much out of control.

I discovered so much remarkable material during those first few days that I struggled to make any sense of it. I searched diligently to find a book that put the various anecdotes together in a comprehensive way that explained the evolution of the office in a way that an outsider could understand. Everything that I found was severely lacking. Some simply parroted the “unbroken chain” line or just emphasized what churches were constructed during their reigns. Others were diatribes against specific popes.

Reluctantly I began putting together a timeline of my own and tried to compile the materials so that I could make sense of the big picture.

I decided to assemble and write what I had learned, starting with a two-thousand-year timeline. It was an extremely long project, but I judged that it would be interesting to others. After all, there were approximately a billion Catholics in the world. Most of them were surely as ignorant of papal history as I had been. The spiritual lives of all of them were ruled by the pope in Rome. It made sense that a significant percentage of these Catholics—not to mention the millions who, like myself, had grown up as Catholics but had “fallen away”—would be interested in learning the many remarkable things that I had discovered.

The original book had nine very long chapters. The emphasis was on how the personalities of the individual popes and the forces of history combined to provide the fascinating story of the survival of the institution, which had property and authority but no standing army, for two thousand years. I don’t remember what the original title was.

When I was nearly finished, I bought a book at Barnes and Noble that had contained a list of names and addresses of literary agents. From that I made a spreadsheet, which I recently found. I sent letters to a dozen or two of the agents. A couple were interested, but I eliminated one who seemed like he might be running a scam. I sent the manuscript to the other one, Daniel Bial4, but he sent it back with a note that he was no longer interested.

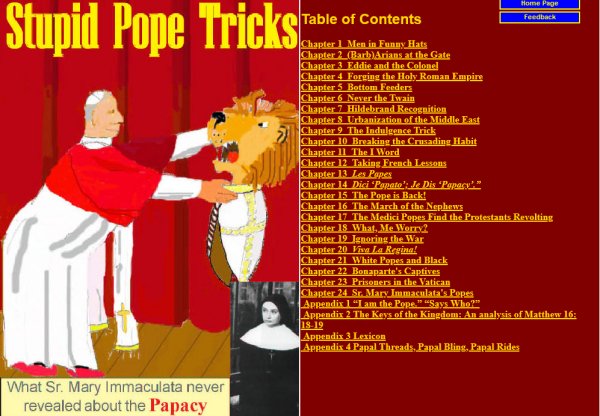

I rewrote the whole book with a new approach. I increased the number of chapters to twenty-four and added a lovable fictitious nun named Sr. Mary Immaculata. She provided the Church’s position on puzzling events. The new version emphasized the trickiness of the various pontiffs. It was now called Stupid Pope Tricks: What Sr. Mary Immaculata never revealed about the papacy. I also added a lot of humorous touches such as a list of “bankable bar bets” about strange aspects of papal history.

I sent the new manuscript to Mr. Bial, but he would not read it. I did not blame him. Who was I to be writing about the history of the papacy? I had no credentials either as a writer or as a historian. I also had no “platform”, which is what publishers call the natural audience that politicians, celebrities, and a few others have for their memoirs.

I therefore decided to post it on Wavada.org using a slightly modified version of the code that I had written for my travel journals, as explained here. This would me allow me to add a lot of images and make it more entertaining. I did not promote it, but a few people stumbled onto the site and told me that they liked it. That was somewhat comforting. I don’t know what more that I could have done.

In my opinion the most fascinating pope was Benedict IX of the eleventh century. I could not find a single author that wrote anything good about him, but the source of most of the calumnies against him was a monk named Peter Damian. Yes, he was canonized as a saint, but he was also a cloistered monk who never visited Rome during Benedict’s pontificates. All of his information must have been second- or third-hand. Perry Mason could easily have gotten all the charges dismissed.

The word “pontificates” in the above paragraph was not a misprint. Benedict IX’s name is on the official list of popes three times. His first pontificate ended when a rival family staged a coup, drove him out of Rome, and elected a new pope named Sylvester III. That pontificate lasted 48 days before Benedict regrouped his supporters and reclaimed the throne. A short time later Benedict, who was still a young man, fell in love and resigned in order to get hitched. A new pope (Gregory VI) was elected, but shortly thereafter the new Holy Roman Emperor came to Italy, decided that he was not worthy, and forced the bishops to elect his choice to replace Pope Gregory. When the emperor departed from Italy, Benedict assumed the throne again. No one seemed to know what happened to his wedding plans.

In all, Benedict was the recognized pope for about thirteen years, the longest pontificate in the eleventh century. It was about the same length as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency.

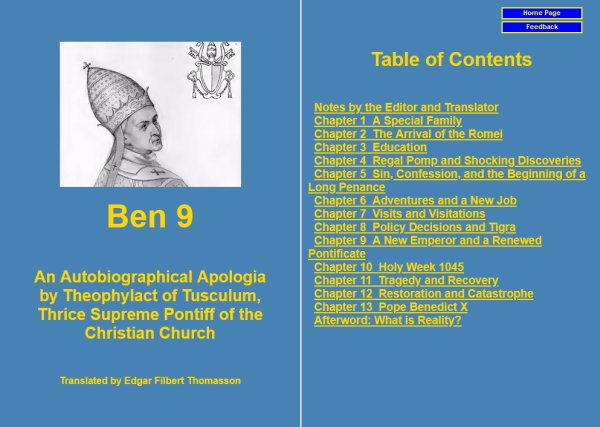

I had a very hard time thinking of any set of scenarios that made sense of the middle of the eleventh century—before Gregory VII, the Great Schism, and the First Crusade. I came up with a few reasonable (to me) assumptions that seemed to explain the whole period. I then wrote a fictional translation of an imaginary autobiography of Benedict IX defending his reputation replete with scholarly footnotes.The result was Ben 9: An Autobiographical Apologia by Theophylact of Tusculum,Thrice Supreme Pontiff of the Christian Church Translated by Edgar Filbert Thomasson. Most of the characters were actual people. The behavior of the most outrageous character in the story, Gerhard Brazutus, was based on accusations leveled by at least one cardinal. I used Occam’s razor to concoct the simplest explanation that I could think of that explained what the cardinal claimed.

My experience with the first book chastened me from attempting to get this one published. As far as I know the only person who has read any version of it is my friend Tom Corcoran.

So, this novel was also posted on the Wavada.org website, along with the text of the story that Northeast Magazine published that has been described here.

Epilogue: I never lost my fascination with the popes. I have not done a lot of research on Benedict XVI and Francis, mostly because they seemed so much more boring than John Paul II. Benedict at least had snazzy shoes and wrote a three-volume history of Jesus Christ. Both Benedict and John Paul did a rather nifty job of tap dancing around the bishops’ approach to the problem of clerical molestation.

My obsession with the popes has continued for two decades. Every so often I have come across an article or book that makes reference to “the pope”. I always make the effort to chase down which pope was involved and what was the context. Almost always the person making the comment misunderstood or misstated the actual event. The last such event occurred in Würzburg on the cruise that I took in 2022. It has been documented here. In this case it was actions by two different popes that were conflated into one story.

Additional blog entries about the popes can be found here.

1. Everything concerning the popes—even the numbering—is complicated. There has only been one Pope Formosus (the name means “shapely” or “physically fit”), and so he will never have a number unless some future pope picks that name. The perpetrator of the Cadaver Synod was known as Stephen VII at the time, but later a previous pope named Stephen, who had been Supreme Pontiff for only three days, was removed from the list. All subsequent Stephens had their number reduced by one. So, the prosecutor/judge of the trial has been known as Stephen VI since that time. There are also quite a few numbers that have been skipped. For example, there is no John XX or Benedict X on the list. Furthermore, in the twentieth century two popes, Cletus and Donus II were removed, because historians determined that they never existed. So, Pope Donus I lost his number.

2. A description of the amazing partnership between Google (now known as Alphabet) and U-M can be read here.

3. The canonized pontiffs are Celestine V, a hermit who never entered Rome and was essentially imprisoned in Castel Nuovo during the entirety of his short pontificate, Pius V, who was most famous for excommunicating Queen Elizabeth I of England and thereby causing persecution of English Catholics, and Pius X, who opposed modernism and saxophone music in the early twentieth century. As of 2023 Pope Francis had canonized three recent popes.

4. Mr. Bial’s agency still existed in 2023. The website is here.